With poor wages and working conditions a major problem in Asheville, Labor Day is an excellent time to look at some changes

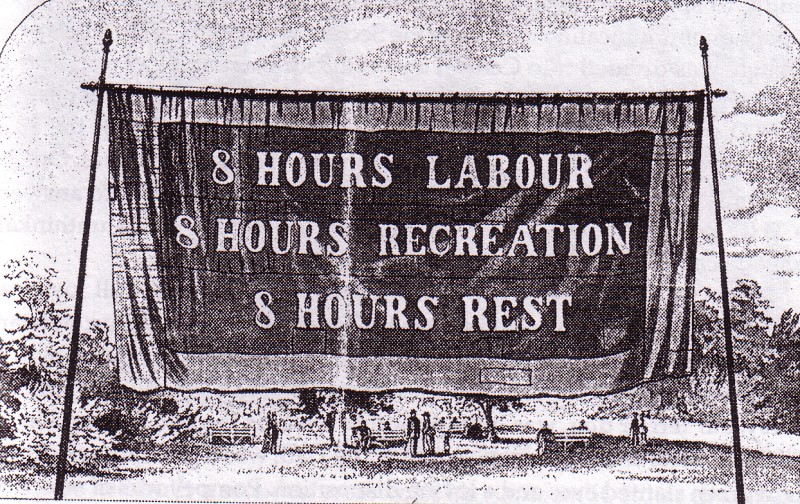

Above: The fight for the eight-hour working day rallied workers around the world. Image via Wikimedia.

It’s Labor Day. In Asheville it’s a day off for some, a work day for many and a day of celebration in parts of WNC where unions are still a point of pride. The day was put forward in the late 1800s by groups like the Knights of Labor, and adopted by an American government that preferred that to giving official recognition to May Day (which should also be observed loudly and proudly).

As a publication that emerged out of a union fight, it should be no secret that the Blade is in favor of better pay and working conditions. I’m in favor of devoting as many days to labor as possible, which is why we’ll report on locals rallying May 1, just as we devoted a column last September and try to inform locals about their rights.

In whatever form, Labor Day is particularly essential in Asheville, because it runs counter to one of the major myths of our city, the myth that prizes names like Vanderbilt and Pack — or even more horrifically, slaveholders like Vance, Merrimon and Woodfin — over the people whose sweat, tears and blood made Asheville.

After all, the Vanderbilts didn’t make Asheville; they just inherited money and spent it. The people, far too many of their names lost to history, who actually forged this city have seen their contributions receive comparatively short shrift.

The myths and symbols of the past help create the present and, if we’re not careful, the wrong ones can warp our future as well. The particularly dark side of the above myth is that, then and now, it makes it easy to revere business and property owners. This myth leads cultures to look at them as the makers of the future rather than the thousands of people waiting tables, teaching students, organizing communities, raising buildings, saving lives, working retail, making art and in a thousand other ways creating the city we live in.

Even some discussions about pushing back at gentrification suffer from this myth, framing the fight as local property owners versus outside corporations, and leaving most of the city’s people out in the process.

So it’s worth taking Labor Day to refocus on the people who actually make Asheville work, and a few very basic, very straightforward proposals that might help them, because they ain’t having the easiest time of it.

1. Unions. Unions. Unions. Unions are legal in Asheville. They’re legal across the country. They remain one of the most powerful tools out there for raising pay or even ensuring that the laws already in place are followed. They’re a reason we have things like, well, the eight-hour day or Labor Day at any date. But they’re largely missing from Asheville, and that absence is one of the reasons the situation for many workers here is so dire.

We are a city, after all, in the least unionized region in the least unionized state in the country, and progressive platitudes aside, business owners here often don’t react particularly well when the topic’s brought up.

But despite obstacles, more unions could help ensure that some of that tourism boom cash actually ends up making it to workers. There’s good evidence that they significantly raise wages in tourism economies.

But much of the local discussion revolves around how to appear to the better angels of business’ nature and get owners to raise their wages (perhaps another impact of the myth that puts their actions at the center of things). While it’s great when a business owner does the right thing, there is no time in history when that has ever solved the problem of low wages on a citywide scale. Power and pressure matter a lot more than goodwill. So far, the sum total of business’ altruism has left our city in a situation where the pay’s not going up and conditions aren’t improving.

There are demands for change on this front, whether it’s the call for “$15 and a union” from fast food workers to waiters and other food service workers organizing to provide information about combatting wage theft and other endemic problems in their industry.

Too many Asheville businesses pay low wages — or even outright ignore labor protections — because they can, because they know nothing will happen to them if they do. Power will be the only thing that changes that, and there’s power in a union.

2. Raise wages past the state average — Ashevillians need to push aggressively for pay to exceed the state average.

Measures vary a bit on how much Asheville’s pay lags behind the rest of the state. One report from 2012 put wages in Asheville and Buncombe nearly $400 a month behind the state average. Take home pay also compares terribly to many other cities in the region. Our area’s median wages, as of the middle of last year, lag more than a dollar an hour behind the state median according to the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics. This is in a state, sadly, that’s not exactly known for great pay. Getting Asheville to better-than-average wages — even just a bit better than average — would bring a huge relief to many locals.

Unfortunately, the trends here are not heading in the right direction, as wages are staying stagnant or even declining despite the tourism boom. A small example of why emerged recently when French Broad Chocolates, a booming business with lines out the door that’s gone through multiple expansions in recent years, dropped their living wage certification and felt comfortable enough about doing so to publicly offer some thin excuses about wanting a “more logical system that develops our staff.”

For context the living wage here, just the amount necessary to make ends meet without public or private assistance, is $12.50 an hour without health insurance.

In addition to being an injustice, low pay puts the whole economy on shaky ground, as we’ve seen with recent news of labor shortages in the local restaurant industry. Turns out a culture of terrible pay for the people making a key sector of our economy work isn’t just wrong, it’s also a really bad idea.

The impact reaches out from there. Because of their sheer size, low pay in the food service and retail sectors pulls down wages in others as well. We have a highly educated populace, and schools that are training talented people, but they’re leaving for places that pay something above bare subsistence levels. Because ingenious people here are stuck working to barely make ends meet, they often can’t save up funds for any number of things, like starting their own business. Our economic diversity suffers accordingly.

Businesses — local or otherwise — that are paying a minimum wage are guilty of impoverishing their workers. Those paying below a living wage shouldn’t pat themselves on the back: the blunt fact is they’re also furthering a major problem. The idea that businesses can’t raise pay in the middle of major expansions and a tourism boom is ludicrous, and we need a larger culture in Asheville that regards it as such and acts accordingly.

This is a goal that can be accomplished. Our city is a major economic hub with a growing reputation; there’s no reason we shouldn’t pay better than average wages. There’s plenty of money here to do so. What there isn’t is a widespread public demand that views a culture of low pay as an evil to be ended, not an inconvenience to be excused.

3. Using incentives and infrastructure to fight segregation — This is an idea brought forward by UNCA professor Dwight Mullen, and it deserves a lot more prominence: it’s time to focus spending on incentives and infrastructure on actively addressing our city’s de facto segregation, something’s that too often missing from discussion around pay and conditions here.

In Asheville this problem is compounded by the brutal history of redlining and “urban renewal” which devastated neighborhoods along with a deeply-rooted African-American business community. The numbers on this front are dire. Just 2.8 percent of Asheville businesses are owned by African-Americans, despite black Ashevillians making up 13.4 percent of our population. In this we also lag behind the rest of the state, where the rate of black-owned businesses is 10.5 percent (as compared to a 21.5 percent African-American population).

So if our local governments are going to hand out incentives — and by all evidence they will continue to — it’s time to look at working to change this. It’s time to require that before a company — any company — gets one red cent in breaks or write-offs, they commit not just to good wages, but to hiring that will help push back against segregation here by ensuring a diverse workforce.

Infrastructure spending needs to be targeted first and foremost at addressing this de facto segregation as well, not just near the “innovation districts” that the city government’s currently focused on, but throughout the whole city. Burton Street leaders, for example, still assert that many of their basic needs remain unmet, despite a well-organized community that developed a detailed plan of how to address them. That seems like a good place to start, but it shouldn’t stop there. Undoing some of the damage of redlining may take decades, and giving priority to the communities hardest-hit by it will mean some major changes in the way the city works, but it’s necessary if justice in Asheville is anything but a hollow word.

—

There are, of course, many other things to be done. But those are, I believe, a good start. A better city is worth fighting for and this Labor Day it’s worth remembering that a better city starts with the people already making it work every single day.

—

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by its readers. If you like our work, donate directly to us on Patreon. Questions? Comments? Email us.