Another year, another legislator trying to force a change in city elections. A primer on the latest plan, the local reaction and what it might mean

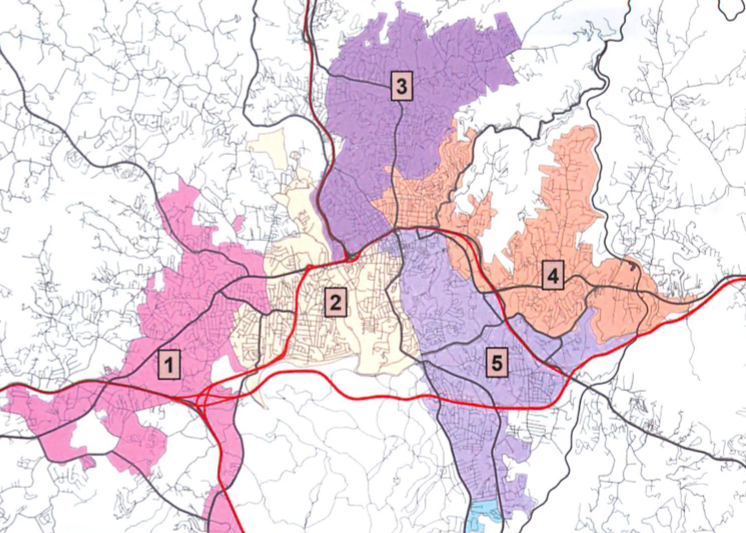

Above: Proposed Asheville City Council districts under last year’s failed state Senate bill. A state legislator is now reviving these districts if local government doesn’t pass ones that meet the legislature’s approval

Yesterday state Senator Chuck Edwards, whose district encompasses Henderson County and part of Southern Buncombe County, including a sliver of South Asheville, filed a bill to force the city government to switch to district elections. If this sounds familiar, it is: late last year, Edwards’ predecessor Senator Tom Apodaca did the same. In a dramatic political upset, that push failed in the state House.

One reason Apodaca’s push failed was that it was a blatant attempt to gerrymander city elections, something the legislature’s also tried to do in Wake County and Greensboro before federal courts halted those plans. He also contravened many of the legislature’s own rules to push the bill forward, fuelling a backlash even from some other Republican officials.

Now Edwards is back with a bill that’s different in a few regards and exactly the same in many others. District elections are a complicated topic, but conservative legislators are pushing them for a reason: they could change the balance of power in local government. Here’s a primer on why this is happening and why it matters.

What’s Asheville’s current election system?

Currently, Ashevillians elect a mayor and six Council members. All serve four year terms, staggered so that three Council members are up for election every two years. This year, the mayor and three Council seats are up for election.

All Ashevillian voters can vote on all those seats. A primary narrows the field of candidates (city elections are non-partisan, so anyone who files can run) down to six and then the top three vote-getters win Council seats. This system is known as “at-large.”

What are district elections and how are they different?

In many cities, candidates run from a specific district rather than the city as a whole. There are a lot of different ways to do this. Sometimes, candidates are only chosen by voters in that specific districts, in others they have to reside in a certain district but voters from the whole municipality get to vote for them. Plenty of cities have a mixture of at-large and district seats.

The topic of district elections compared to at-large ones is a complicated, with arguments on both sides. Proponents of districts assert that they ensure no area of the city doesn’t at least have a voice at the table. Supporters of at-large systems counter that city officials make decisions that impact the city as a whole, and thus should face all of its voters, not just a small portion.

One common argument for district systems — and a key one — is that they increase minority representation. In some cases, they certainly can. In my hometown of Elizabeth City, for example, the federal government and civil rights groups pushed a change to district elections to better represent the town’s many African-American voters. There, the left and progressives supported districts and conservatives an at-large system.

However, that also depends on geography and how the district boundaries are drawn. District elections can increase minority representation if that minority’s mainly concentrated in one part of a city. In Asheville’s case, however, minority voters are concentrated in multiple neighborhoods throughout different parts of the city. Under the current system, if they vote for specific candidates, their support can prove decisive overall (there’s a good argument this happened in 2015). But depending on how districts in Asheville are drawn, there’s a real possibility they could actually reduce African-American electoral power.

That might be important in the future, as state plans to gerrymander local elections in Wake and Greensboro were stopped because federal courts found that they decreased African-American voters’ representation.

What is Edwards proposing?

Edwards announced his intent to force the city to switch to districts on Feb. 28, in an email Mayor Esther Manheimer read to Council the same night. The bill sets a Nov. 1 deadline for Asheville City Council to draw up its own districts for all six Council members (the mayor would continue to be elected by all city voters). The three Council members elected this year would serve two-year terms, with district elections starting in 2019.

Importantly, if local officials did draw up those districts, they would then have them reviewed by the legislature. Edwards, in the email mentioned above, phrased the opportunity for Council to shape the districts as the carrot, though he and his colleagues would still review the district lines and have final say on them, meaning they could easily alter or send them back.

Then there’s the stick: if local officials don’t draw up districts by Nov. 1, Apodaca’s bill — which Edwards basically cut-and-pasted proposed districts from — goes into effect.

Why do conservatives keep pushing district elections for Asheville?

Edwards, like Apodaca before him, claims that he’s doing this because he’s received “a great deal of feedback from the citizens of Buncombe County.” But an investigation by the Asheville Citizen-Times last year found that rather than some groundswell of push against the current system, the calls for change mostly came from members of the Council of Independent Business Owners, a right-wing lobbying group. This year, former Council member Joe Dunn and other conservatives pushed for district elections at a forum held by the very same group.

The idea of district elections in the city isn’t new, and it wasn’t always just tied with the right wing, as the Blade examined in an analysis last year. There was dissatisfaction with the current system over the years, mostly due to the fact that many local elected officials of multiple political stripes historically come from wealthy neighborhoods in North Asheville. Money and connections help, after all, especially in generally low-turnout local elections.

But, like all of politics, this boils down to power. While district elections were occasionally broached before, conservative legislators didn’t take them up until the local right-wing started getting repeatedly trounced in local elections.

The roughly decade-long fight between the city’s conservatives and progressives teetered back and forth until the late 2000s. But when the conservative decline came, it came swiftly. As recently as 2005, conservatives (in that case two Republicans and two conservative Democrats) held a majority on Council. Six years later there were no Republicans on Council and even a fairly popular conservative Democrat barely held his seat.

Around the same time, however, the general assembly began shifting farther to the right, a change preserved by what federal courts later found to be racial gerrymandering of state legislative districts to cement their control. In 2011, then-Rep. Tim Moffitt changed Buncombe County Commissioners’ races from an at-large system to district elections (based on the state House districts). The next year Republicans went from having no seats on the commission to almost taking a majority.

In 2013 Moffitt drafted a bill to force the city to switch to district elections, but he never filed it and lost his re-election bid the next year.

The city’s 2015 elections harshly illustrated how far local right-wing electoral power had fallen over the course of a decade: despite a year with a lot of dissatisfaction with the current Council, three experienced conservative candidates all failed to make it past the primary. The election ended up a fight between different viewpoints among progressives, centrists and more left-leaning voters.

In addition to the changing nature of the city, part of the reason for the electoral wipe-out was that local conservatives had shifted farther to the right as well. Candidates comparing the LGBT pride flag to the Nazi flag, amazingly, don’t exactly gain traction in today’s Asheville, even among center-right voters who would be key to any local conservative resurgence.

Rather than deciding to change approaches or platforms, some local conservatives have instead called for Raleigh to intervene in hopes of getting seats on Council anyway.

The plans drawn up by Apodaca last year, and revived by Edwards this time, are a flat-out gerrymander of local elections. They place multiple current Council members in the same districts, which would force them to run against each other in the future, and sliced downtown into three separate pieces. While the city would still likely prove more difficult terrain than the county commission did — Asheville’s a pretty left-leaning place no matter how you slice it — it would give the local right wing more favorable terrain than they currently enjoy.

How are local leaders reacting?

Not well, as one might expect. After hearing from state legislators following the failure of the previous bill, Council had already agreed to assess public interest in shifting to a district system and possibly put the matter to a referendum. They were preparing plans for polls and a town hall when Edwards told them of his “hope that your discussion may revolve more around how to district and forego the discussion of should we district.”

Council members used terms like “disappointing,” “overreach” and “affirmative action for Republicans” to describe Edwards’ plans, and decided to go forward with polling locals and setting up town halls anyway.

This follows years of political fights over state and local control, including the state trying unsuccessfully to take Asheville’s water system in a multi-year court battle that only ended last month.

Ironically, the repeated attempts to press districts on Asheville have solidified support for the current system. Before this, many locals were lukewarm about the current at-large set up. A 2007 attempt by some local progressives to shift the city to partisan elections failed in the face of an overwhelming backlash from across the political spectrum. Especially in the late 2000s, when resentment of the preponderance of north Ashevillians on Council was particularly high, there was an opening for a local push for districts. If city residents had seen them as fairly drawn and support had come from across the political spectrum, they might even have passed.

But the fact remains that Asheville is simply not a conservative city and the local right-wing hasn’t exactly proved politically nimble or well-organized over the last decade. The fact that district elections are now largely associated with an unpopular political faction and a legislature that Ashevillians widely despise has made their long-term prospects a lot worse than they were before.

Will the bill pass?

Maybe. Republicans have a lock on both chambers. Edwards doesn’t have Apodaca’s clout, but he doesn’t have his baggage and long list of enemies either. The procedural hurdles that led some House members to check the Senate last time aren’t a factor this time around.

At the same time, those weren’t the only reasons House legislators rejected it. The court rulings against the Wake and Greensboro plans had left some hesitant to press their luck on the judicial front, a harsher look from the federal courts at how the state draws its districts in the future might go disastrously for them. Also, even some conservative state legislators felt that the overreach into local government elections had gone too far.

It’s hard to read the tea leaves on this one. The bill sailing through or running into serious hurdles are both real possibilities.

Last time, public opinion played a role too, and that’s where locals come in. If you want to email all the state legislators, there’s an easy tool to do so. The city will hold a town hall on the issue next month and if you have strong feelings on the topic, you should probably come out to that as well. If last year’s upset proved anything, it’s that nothing in politics is inevitable.

—

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by its readers. If you like what we do, donate directly to us on Patreon or make a one-time gift to support our work. Questions? Comments? Email us.