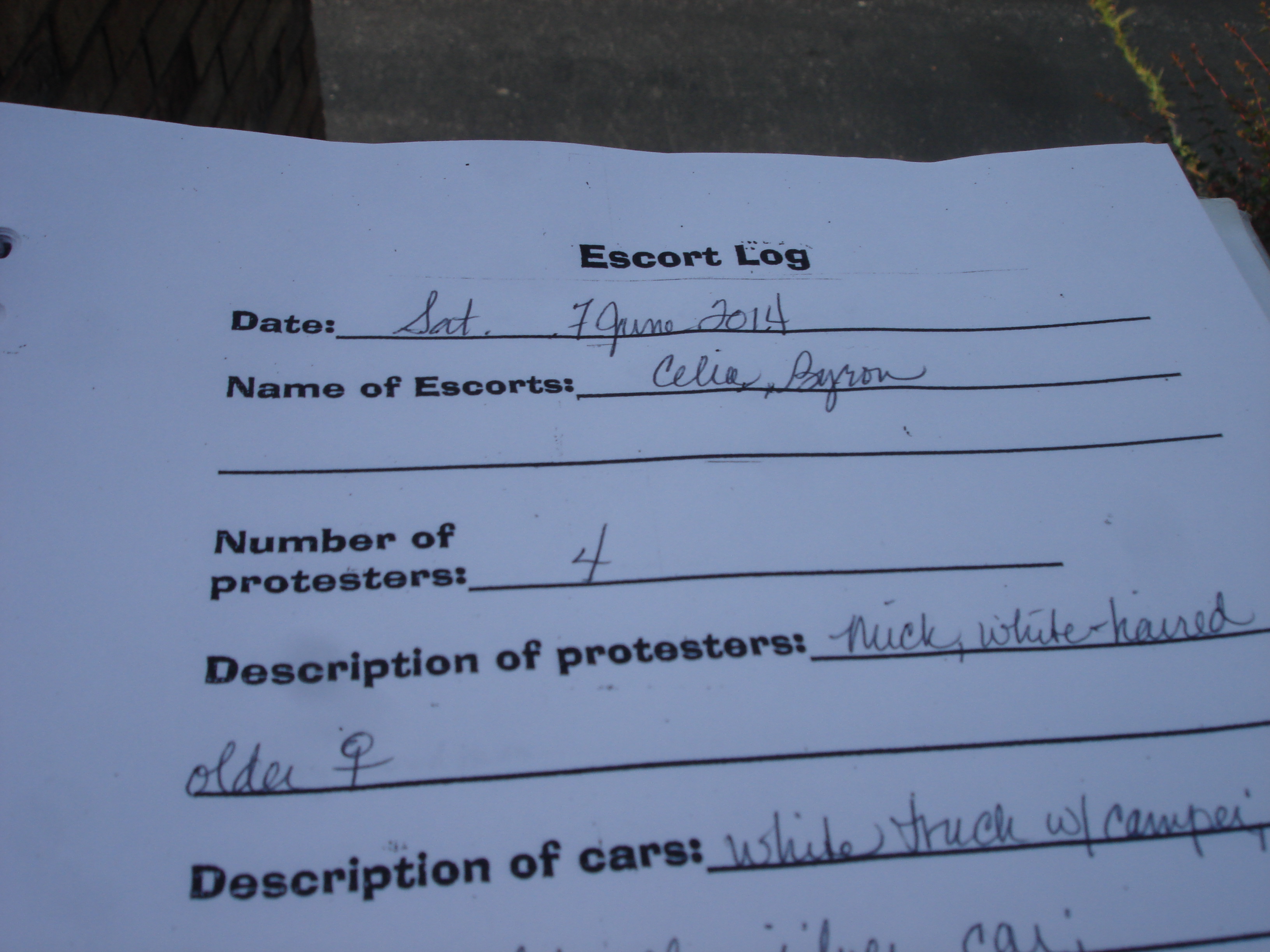

The log for the volunteer escorts at the Femcare clinic, June 7. Photo by Byron Ballard.

At the end of this month FemCare, currently the last clinic in the Asheville area providing abortion services, will close. Last year, the clinic was controversially shut down for nearly a month by NC inspectors during a fight about new state legislation sharply restricting access to abortion. For almost a decade, local activist, author and Pagan clergy member Byron Ballard worked as a volunteer escort, accompanying women in and out of the clinic to ensure their safety. Here she tells the story of her last shift. -DF

By Byron Ballard

I get the Saturday morning coffee ready on Friday night. This is a leftover from the days when my escort shift at FemCare began at 7:45 am. I could roll out of bed at 7, press the button on the coffee-maker and get dressed while it dripped, filling the kitchen with the unmistakable scent of morning in America. A piece of toast and a travel mug of milky coffee and I would be out the door by 7:35 and on my way to Orange Street. When the general assembly decided that women’s health in North Carolina needed to be subject to the state’s tender mercies, the arrival time shifted to 8:45. But the coffee ritual was set by then—as set as the rest of the routine.

NPR on the radio. Approach the clinic’s driveway entrance. Count the protestors. Any new faces? New posters or other paraphernalia? Turn in slowly, rocking over the big speed bump, try to avoid the person who steps into your path to hand you a pamphlet. Park a couple of spaces up from the fence that separates the patients from the obnoxious citizens practicing their First Amendment right to free speech by shouting lame platitudes at women going to the doctor.

June 7 was my last day escorting because FemCare—“the health center” is what I called it when speaking to patients—is closing at the end of the month. Another clinic—by non-profit Planned Parenthood—is going through the complex tangle of state bureaucratic nonsense and won’t be open before Femcare closes. That leaves a gap in services in WNC, unless a woman has enough money or insurance to go to the hospital and have a termination procedure with her ob-gyn. Many don’t.

This last Saturday is pretty much the same as it has been all along. After doing this gig for almost a decade, some of it is ingrained—checking the protestors, parking near (but not too near) the fence. Getting out of the car, I put my keys in one pocket and my phone in another, just in case. If someone is sharing my shift, there’s a quick hug or a joke as we put on our orange vests and fill out the top part of the paperwork. Day and date. Name of escorts. (Or “deathscorts” as we sometimes hear from the holy peanut gallery.) We leave the rest of the form blank until all the protestors arrive. We count them, make notes on the usuals, note the color/make/model of their vehicles.

The clinic isn’t quite open yet, so if patients arrive early, we go out to their cars and invite them to remain there—to stay warm or cool or to finish their coffee—and tell them we’ll come back for them as soon as the clinic opens. We need to remember the order they arrived in and escort them in that order. If there are two escorts, we go to either side of the vehicle. I’ll say, “We’re here from the health center to walk in with you.” We might hold their car door as they get out. Then we put ourselves between them and the comments that immediately begin down on the sidewalk.

I’m not sure if other escorts did this but I always started a running patter, something like this—I’ll be talking about all sorts of things so focus on my voice. It’ll be like a late night monologue, only I’m not very funny. I’ll talk about your shoes—gosh, those are cute! Or how far you had to drive—did you have far to come this morning? Black Mountain? Oh that’s not so bad. How was the traffic? Gosh, this is (fill in the blank) weather, isn’t it? Does that RAV get good gas mileage?

This unfunny non-conversation would take us up the clinic steps and through the heavy door where they were greeted by Darren, the security guy. As the door closed behind them, we’d hear him ask for their ID and they’d go from there to the doctor’s waiting room, where they’d check in with the receptionist.

But we escorts didn’t see that part. We closed the door and turned back to the parking lot and onto the next patient.

One of my favorite things to do was to meet the doctor when she arrived. I’d stand by the driver’s side door and wait for her to open it.

For a while, the door would only open from the outside, so she’d either roll the window down and open it or I’d open it for her. When the state closed the clinic down last year, she actually had enough free time to get the door fixed. So there was a little silver lining in all that mess. “Good morning, Doc C,” I’d say. “Welcome to your clinic.”

We’d chat as we walked up the steps and I’d follow her, standing between her and the people on the sidewalk until she went through the heavy door to be greeted by security.

Sometimes extra folks would arrive—translators to help the Spanish-speaking patients or the doulas who sat with the patients and guided them through the morning. And women would come in who weren’t there for an abortion but had come to pick up a prescription or for a follow-up visit. Mostly it all went smoothly, without a hitch. Sometimes the patients or their support person would be shaken and weepy. Sometimes they would be defiant, shouting back to the sidewalk people.

The protestors were usually the same, with some variations. For a while, there was a group of young people—a Sunday school class or youth group maybe—and their minders. They stood across the street in a row, sometimes praying aloud or singing softly. Sometimes a priest would arrive with a little table and set up all the stuff for a Eucharist ceremony. For a while, there was a man who blew a shofar and sometimes danced with colorful flags on poles. I wasn’t sure what the flags were for but I thought the shofar had something to do with the Walls of Jericho.

So the last Saturday was much like the first one. I escorted patients and their support person inside, discussed gardening with my sister escort, made some photos of her and Darren to remember my time there.

I used to think how stupid and terrible it was that women had to be subjected to that abuse as they went to their doctor’s office for a relatively simple procedure. But now I think about the women who will have to go farther afield or lose a day of work or maybe just won’t be able to go away at all. They don’t have very much choice, do they?

I took on this volunteer gig to serve a need, to be helpful, to be strong for women. Because I am a woman and a feminist and the mother of a daughter. And I did it because it wasn’t about me. The First Rule—Do Not Engage—meant that I left my advocate-self at home. I wasn’t there to debate law or policy or to change people’s minds. My job was to wear a bright orange vest, to walk to the car, to be calm and pleasant and professional. I was to keep these patients as safe and calm as I could, given the circumstances.

When my shift was over on Saturday, I finished the paperwork. took off and folded my orange vest and went to my own car.

I got in, locked the doors and left the parking lot, waving to Darren as he stood on the porch, in front of the heavy door. Maneuvering over the speed bump, I looked both ways while ignoring the protestors on either side, and headed home.

Email questions or comments to ashevilleblade at gmail. If you like our work, support the Asheville Blade directly on Patreon.