Despite Asheville’s aspirations of being a first-rate city, this is a place dangerously focused around cars. How that happened and how we can change it.

Above: A pedestrian tries to navigate Tunnel Road. Photo by Don Kostelec

Human beings are designed for walking. Our streets are not.

This was evident in the recent death of Yvonne Lewis along Merrimon Avenue in North Asheville.

Engineers, law enforcement officers and attorneys are evaluating what contributed to this tragedy. Was she in the crosswalk? Was the motorist at fault for not yielding? Why was the crosswalk not replaced after a recent project? Should we erect a signal in an attempt to keep it from happening again?

Once these professionals are satisfied with their evaluation one primary contributing factor cannot be disputed: the result is almost always fatal when a car driven by a person at 35 mph collides with a person who is walking.

We’ve designed our roads with the hope that it doesn’t happen, but have done very little to prevent it.

In the lingo of highway engineers, roads like Merrimon Avenue are called arterial corridors. For the rest of us they are, more accurately, called traffic sewers.

The speed limit along Merrimon Avenue is 35 mph, which means that almost any collision between a person driving a car and a person walking on the route will be a tragedy. Driveways are so prevalent that a pedestrian must remain alert along the entire route because motorists are trying to enter and exit the route as fast as they can for fear of being hit by other motorists.

According to Smart Growth America’s Dangerous By Design map of pedestrian fatalities, four pedestrians prior to Lewis have died along Merrimon Avenue since 2006. Safety investigations are typically conducted by engineers after any fatality, but when the victims are not in a motor vehicle, these investigations rarely result in any changes.

“One of the real challenges – not just in Asheville but across the country – is that most of the people responsible for designing, maintaining, and policing American streets have what we call ‘windshield perspective,” Heather Strassberger, a former planner for the Asheville area’s metropolitan planning organization who now provides technical assistance to Massachusetts communities for WalkBoston, says. “When the engineer conducting a safety study or the police officer investigating a pedestrian crash has little experience walking in a hostile environment it can be hard for them to get their head around why a pedestrian wouldn’t have walked a quarter mile out of their way to push a button and wait over a minute for a walk signal instead of crossing directly where they needed to go.”

Pedestrian safety became a hot topic in Asheville in 2014 when the city was identified as having the highest per capita pedestrian crash rate of any city in North Carolina. The study was produced by the Highway Safety Research Council at UNC Chapel Hill using data generated by North Carolina Department of Transportation.

All of this has prompted NCDOT to act by securing the services of an engineering firm to conduct a citywide analysis of pedestrian safety issues.

A key element to watch for in this study is how much the speed of the roads are evaluated as a contributing factors in the crash and fatality rates for pedestrians. It is easy to evaluate the presence or lack of facilities and crosswalks and make a determination on their impacts. It is harder for transportation agencies to accept that motorists traveling at high rates of speed on roads designed exclusively to move traffic through city neighborhoods are the culprit.

According to NCDOT data, 29 pedestrians died on roadways in Asheville between 1997 and 2012 with 25 of those fatalities (86 percent) occurring on streets with a speed limit of 30 mph or greater. By comparison, 52.7 percent of the total pedestrian crashes and 66.0 percent of disabling injuries to pedestrians occurred on roads with speed limits of 30 mph or greater.

A little history

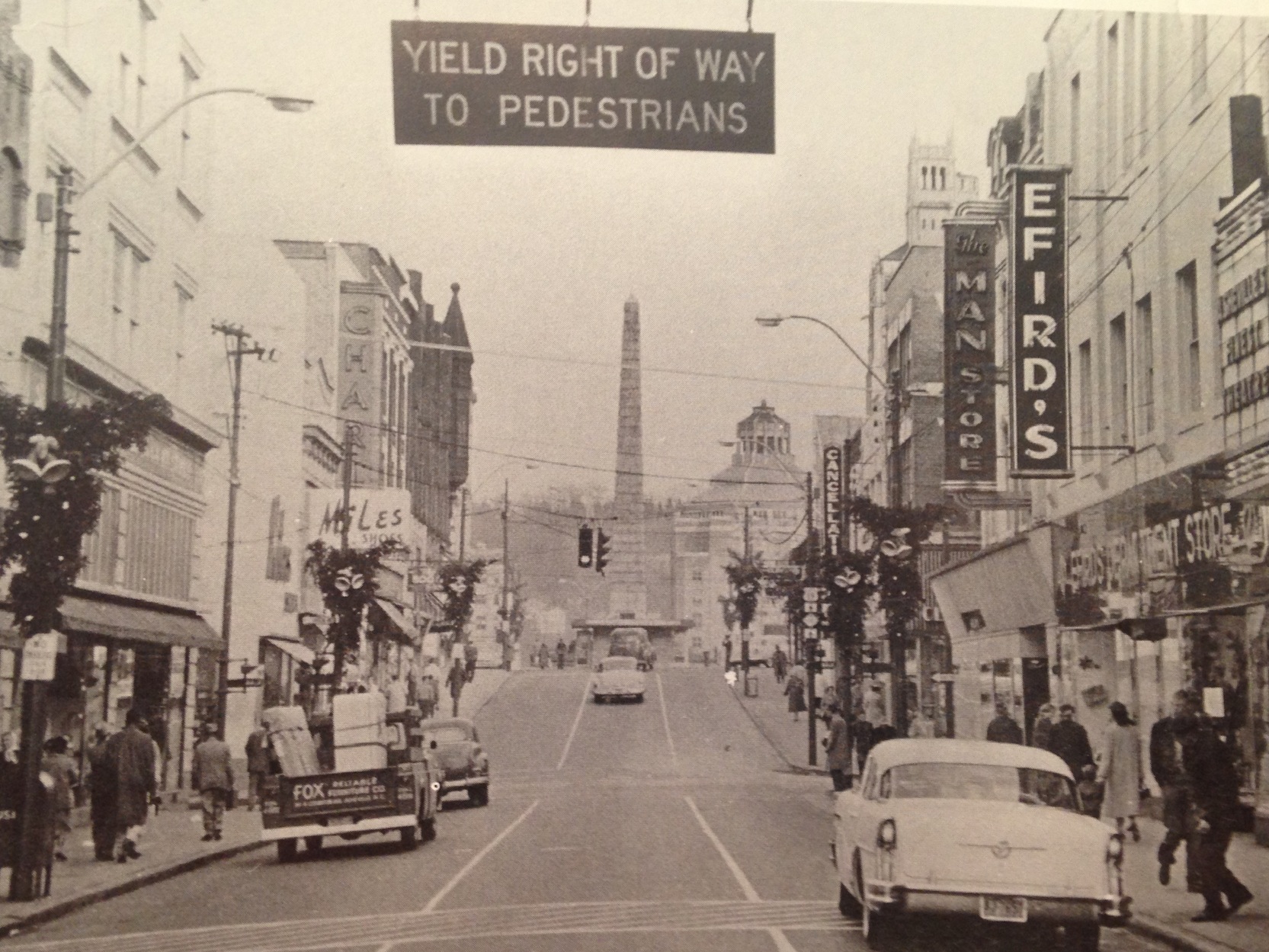

Pedestrian right of way sign in downtown Asheville, 1960s. From UNCA, D.H. Ramsey Special Collections.

The manner in which our city’s current transportation system is engineered is based on the premise that automobile movement is king and everyone else is an impediment to traffic. But that’s only a recent practice, even for Asheville.

The city’s urban pockets such as Downtown, Biltmore Village and the Haywood Road corridor still have the bones of a safe walking environment. The urban feel of these areas, created by the design and placement of buildings, fewer driveways, and slower vehicle speeds contribute to a greater sense of safety for people who are walking.

Believe it or not Merrimon Avenue, which is also US Highway 25, once looked that way. You can see remnants of this in the buildings along the route north of Chestnut Street to Coleman Avenue. As traffic volumes increased prior to the construction of future Interstate 26 it was determined that the flow of vehicles was too important for the route to continue to be a two-lane road. The street was widened, residents abandoned the homes that are now businesses, and pedestrians who still needed to walk along or cross it were deemed second class citizens.

In the book Fighting Traffic author Peter Norton chronicles the transition in the United States from valuing streets that were meant for people to streets that were designed exclusively for automobiles. In detailing this transition, Norton notes that “all (road user) groups agreed that some of the effects of new cars on old streets were disastrous.” He asserts this early argument fostered hopes that common sense solutions could be found. If all groups did their part, perhaps street problems could be solved.

That was 90 years ago. Common sense was abandoned shortly thereafter.

Merrimon Avenue is designed to move motor vehicles as fast as possible through 2.3 miles of urban development from the Beaver Lake area to Interstate 240. No other transportation function is deemed relevant. Yeah, it has sidewalks and a few crosswalks but they meet the minimum design requirements, at best.

Other once-walkable urban thoroughfares were prescribed that same fate: Biltmore Avenue, Charlotte Street, College Street, and Hendersonville Road to name a few.

When looking at pavement width, Haywood Road through West Asheville near Brevard Road is as wide as Merrimon Avenue near Chestnut. What’s the difference? Some of that asphalt on Haywood Road is used for on-street parking, as it once was along Merrimon.

Haywood Road was destined for the same fate as Merrimon at one time. This is evident by the width of the Riverlink bridge which until recently resembled a five-lane barrel of a shotgun aimed right at the heart of one of Asheville’s most vibrant neighborhoods. Luckily for West Asheville the demand never arose to blast traffic through the neighborhood. Unfortunately, NCDOT is left with a behemoth of a bridge that was over-built to accommodate future conditions that never materialized.

Meeting the Standard

Our roads became imbalanced from a modal perspective as transportation engineers and planners seized a kind of ownership role over our streets at the onset of the motoring age in the early 20th century. Through the support of elected officials and Chambers of Commerce in the 1920s (the traffic engineering profession was created by chambers, according to Peter Norton’s research) this sense of entitlement spawned our modern dilemma along Merrimon and on many other local streets.

Asheville’s How Shall We Grow? plan illustrates how this ownership role was still alive and well in 1970. It prescribes a fate to downtown Asheville that we are still recovering from today. The Transportation System element of that plan states downtown “parking needs to be removed [from streets] in order to make more lanes available to carry traffic.” It also says “short jogs in the streets need to be removed in order to allow more through movement in the [Central Business District]” and the unloading of passengers from buses needs to be “controlled more forcefully and in the way that will benefit movement of traffic.”

A loop was proposed along the southern boundary of downtown, which is why we have the massively over-built Charlotte Street from College Street to Biltmore Avenue. That loop, which was to run somewhere south of Hilliard and connect to Patton Avenue (now I-240) near Chicken Hill, was never realized.

The 1970 plan calls Merrimon Avenue “inadequate.” It had the same four lanes then as it does now south of Weaver Boulevard.

All of this stemmed from a desire for engineers and transportation agencies to meet “level of service” guidelines that focus exclusively on vehicular delay. No other factors, including pedestrian safety, are considered in such analysis.

This is because a licensed professional engineer working on roadway and traffic facilities follows two key doctrines.

One is a document known as “The Green Book,” a publication of the American Association of State and Highway Transportation Officials that guides the geometric design of streets, interstate highways, bridges, culverts, guard rails, you name it.

The Green Book influences the design of our cities far more than the most stringent zoning ordinance ever could.

The other is the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD), which prescribes how lines are painted on roadways, how traffic signals are timed, how we color road signs and how much time we should give pedestrians to cross at a traffic signal. The MUTCD is the reason why a speed limit sign looks the same in North Carolina as it does elsewhere in the United States.

Engineers are taught that these documents are the standard by which they design every element of a roadway. Following these standards, in theory, shields an engineer and a public agency from lawsuits. Prove that you followed the standards and you cannot be blamed for the deaths that may result from them.

There is a false assumption that when it comes to pedestrian safety that following the standards results in safer conditions for the people who walk. Paint the crosswalks correctly, be sure the traffic signals are programmed to give them adequate time to cross a street, make sure that curb ramps meet the proper configuration and voila, pedestrian heaven!

“You may see an engineering based assessment that the distance between marked or signalized crossings met a standard – but not a real world understanding of the conditions in which that pedestrian had to operate,” said Strassberger. “The average American driver has that same lack of perspective on what it’s like to be a pedestrian or bicyclist in an environment designed for cars and that impacts how they drive as well.”

Where do we turn?

I have walked the length of nearly every major route with sidewalks in Asheville in the past year. It is not a pleasant experience. On the Smokey Park Bridge you are confined to a cage not fit for a zoo animal. Along Merrimon Avenue you feel like you are walking along a ledge of the Grand Canyon, fearful that one false step will be your last. In the Beaucatcher Tunnel you inhale fumes from cars speeding by less than two-feet away as you are wedged between the tunnel wall and a concrete barrier.

These are deplorable conditions for a first-rate city.

And it’s not likely to get noticeably better along state highways in the near future.

Just as NCDOT was beginning to incorporate its Complete Streets policy—a policy that states that roads must be safe and accessible for all modes and all users of all ages and abilities—the North Carolina General Assembly passed the Strategic Transportation Investments law.

The 2013 law forbids the state DOT from using state funds on state highways that were designed by state engineers to address the needs of the state’s pedestrians who are dying at a rate of one every 46 hours. The only way to get pedestrian facilities through DOT means is if they are part of a highway widening project and a city agrees to pay for part of it.

Ultimately, the city must counter this by taking greater control of local surface streets currently managed by the state. If the state has no ability to address the needs of pedestrians or bicyclists along urban streets that are not planned to be widened, why shouldn’t the city control its own destiny when it comes the livability of these routes?

The best part is the city can do this without the fear of massive gridlock and an unfounded belief that traffic congestion is somehow a detriment to economic development. An August 2014 article in the Institute of Transportation Engineers Journal — Decisions, Values and Data — addresses the biases in transportation decision-making and cites a study of 88 metropolitan areas in the United States that found “economies do not stagnate as a consequence of traffic.”

In some ways this has already been proven in areas of Asheville. The removal of travel lanes along College Street downtown did not create mile-long traffic delays. Pedestrians and bicyclists were prioritized and it created a beautiful gateway to downtown. Engineering conventions would have never predicted the transportation system downtown could absorb traffic in such a manageable way.

Biltmore Village, while not very walkable throughout, is congested based on every popular transportation metric but remains one of the city’s most thriving business districts. Traffic queues along Haywood Road regularly stretch out more than 1,000 feet and it is the city’s most bustling neighborhood. We can easily afford to prioritize pedestrians to a greater degree in these areas.

Just like Biltmore Avenue and Haywood Road, Merrimon Avenue is still designated as a state or US highway, but it really serves no function in the state’s overall highway system.

To the state’s credit, Merrimon and Coleman intersection is now approved for a signal in the wake of Lewis’ tragic death. It will meet all the necessary standards and will probably improve conditions for pedestrians crossing at that intersection.

But has this response influenced our investment practices enough to understand the underlying issues?

Less than 1,000 feet from where this tragedy occurred, safety is cited as the primary justification for the state adding new turn lanes along Merrimon at Weaver Boulevard six years from now. NCDOT’s program says the project will “improve” the intersection as they intend to make it easier for motorists to travel at higher rates of speed.

Unless things change, the road will remain hostile to pedestrians doing what they were designed to do.

—

Don Kostelec is an award-winning professional planner, WNC native, avid cyclist and safety advocate.

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by its readers. If you like our work, donate directly to us on Patreon. Questions? Comments? Email us.