Behind the numbers, criticisms, praise and efforts to reform how Asheville accesses public information about its own government and its records

Above: Workers on scaffolding outside City Hall during recent renovations. Photo by Bill Rhodes.

Every year Sunshine Week, which ended Saturday, marks a time dedicated to informing the public about open government. This article was a collaboration between the Asheville Blade and the Asheville Citizen-Times to give the public a glimpse of how its local government is faring on the important issue of open records.

ASHEVILLE – Under North Carolina law, the press and every citizen has access to most records produced by their government, including their local governments. The law specifies that records are “the property of the people.” But in reality, access depends on the attitudes and actions of local government staff.

“Our democracy is based on having an educated public,” North Carolina Press Association Attorney Amanda Martin says of the importance of open records. “The best way for the public to be educated about governmental issues is to see them and hear them and draw judgments for themselves.”

Recent years have seen controversy over the state of open records in the city of Asheville, including two lawsuits involving the Citizen-Times, among other local media. The perspective of local journalists who’ve had to deal with city government’s process over the years range from harshly critical to praise for some improvements. Numbers reveal that records requests have increased while response times vary widely and some locals are pressing to make all city information “open by default.”

Streamlining

In recent months, the city of Asheville has made efforts to “streamline” its process, says Dawa Hitch, director of communications and public engagement. Last month, the city issued an updated primer on open records requests. Citizens can now send requests to a specific email address, opengov@ashevillenc.gov, set up for that purpose. While state law doesn’t specify a time frame for a response, the city’s policy states staff should reply within five business days.

Hitch also highlights the city’s open government and project web pages as a way they’re trying to put more information into the public’s hands, “so folks can hopefully find information easily.”

With the recent departure of Brian Postelle, the public information specialist who, along with Hitch, often handled records requests, the city is searching for someone else to take up that position. Aside from that, “honestly it’s not really that different from what we’ve done in the past,” Hitch claims.

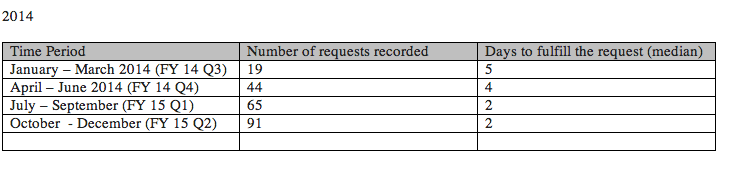

Records released by the city of Asheville showing the numbers of open records requests it received, and the median number of days to answer them, from 2012-14.

Records released by the city about requests from 2012-14 show the numbers can vary widely. Overall they have risen in recent years, with 189 requests in 2012, 264 in 2013 and 219 in 2014.

Median response times have, overall, narrowed.

In the first quarter of 2012, for example, the city received 40 requests and the median time to get the records into the public hands was seven days. In the final quarter of 2014, the city received its highest number of requests, 91, in the whole period and the median response time was down to two days. But in the first quarter of 2014, the city received 19 requests, its lowest number during the whole period, and five days was the median time to answer them.

Hitch notes that the numbers don’t tell everything. There’s a big difference in requesting all emails about the city dealing with a public protest, for example, and obtaining a copy of a contract, though both come across in the numbers as one records request.

Varying views

Recent history has seen the press and the city sometimes at odds over open records. In 2012, an alliance of local media, including the Citizen-Times, sued the Buncombe County District Attorney’s office and the city over access to an audit of missing evidence from the Asheville Police Department evidence room. (Disclosure: working for Mountain Xpress at the time, this reporter participated in that lawsuit.)

The case was thrown out on a technicality, but became a significant public controversy. Last year, outgoing District Attorney Ron Moore released the records.

In 2014, a Citizen-Times investigation revealed Asheville Police Department was recording peaceful protests without a clear policy for destroying or retaining those records, and city officials gave contradictory explanations for the purpose of those videos. The newspaper has sued to obtain the tapes.

Dealing with local government for 15 years, Citizen-Times investigative reporter Jon Ostendorff sees that “they are putting a lot more effort into managing how they release records. Generally, I think that has slowed down the flow of information.”

When he started, he says public officials were usually more open with the press, now there’s a “greater emphasis on managing the flow of public information. I understand why they do it, the city’s growing, but I don’t think it’s good for the public.”

As an example, he notes city staff recently refused to release initial results of a survey about conditions among APD officers, citing that it might damage morale, something not allowed under open records law. The city eventually released the documents but Ostendorff believes “it’s a great example” of the reluctance to release controversial information.

At the same time, “the city does a pretty good job releasing routine things and in fact today they make more records immediately available to the public than in the past.”

WLOS investigative reporter Mike Mason is harshly critical of the city’s process.

“In Asheville, I feel there’s a climate of secrecy and officials feel they have the right to do whatever they want,” he wrote in an email. “They need to be pressed to comply with the law and be held accountable.”

Mason cites contradictory explanations from city staff about police overtime records as an example of “egregious” behavior when it comes to answering open records requests.

Citizen-Times reporter Joel Burgess, who first started covering Asheville’s government in 2007, says things have improved overall.

“I feel like in general the city has gotten more responsive,” he says, but “there has been a recent period where it’s gotten very tough to get things.”

He attributes the recent issues to staffing, more people making requests via email and “a bit more clamping down” when it comes to controversial issues like the police survey.

“In the end the goal is to serve the public,” Burgess says. “So we want to push and we want that information but we also have to understand human limitations.”

“We’re always open to feedback,” Hitch says when asked if the city’s process is in need of improvement. “The city takes transparency seriously and we’re always continuing to look for ways we can make information accessible to people.”

Property of the public

But requesting records isn’t just the province of the press.

“The law says anyone can request public records,” Martin emphasizes. “You don’t even have to be a North Carolina resident.”

Nor do those requests have to take any specific form, though she notes that in many cases an email or written request “could make it a little more efficient or clear.”

Drawing from his own experience, Ostendorff recommends knowing the state’s open records law “backward and forward” including familiarity with exemptions. “My advice is to cite that law right off the bat” and follow up repeatedly, he said.

Burgess advises members of the public to “be as specific as possible” and talk to officials about what they need.

“If they will explain to the person getting the records what they’re after, sometimes they can get guidance,” he says, but to also be persistent if they don’t get answers.

“Our system wasn’t set up with the idea that people were supposed to sit back and trust their government. Even though sometimes it’s small-town government where you know the mayor and you like them, things sometimes go bad when they’re kept in the dark.”

Open by default

Over the past few years Code for Asheville, an offshoot of the Code for America group, has sought to improve access to government information. Now, the group is crafting an open data policy for the city.

The ordinance is drawing on advice from the Sunlight Foundation and similar rules in cities like Raleigh to ensure the city releases more data and records over time and improves its technology accordingly.

“We know that there’s some support on City Council for an open data policy,” Patrick Conant, one of the group’s leaders, said. “Our goal is for as much public information as possible to be available.”

The city has an open data portal, and in 2013 set up a site to make most police reports quickly available to the public.

What’s defined as data or records isn’t always clear, but the eventual goal is “open by default,” meaning all records and data legally available will be open to the public without having to go through a city department.

But there are technical challenges as well, Conant notes, like how an “open by default” system would redact parts of public records that are exempt under open records law.

Notably, at Asheville City Council’s retreat this year Hitch asserted that open data efforts should leave open records aside, while Chief Information Officer Jonathan Feldman said open government improvements must include both.

Hitch says she still believes the distinction between records and data is important, and “they’re two different things,” but “there is an effort to make both as accessible as they can be and we’re constantly looking at ways that we can make it easier and better.”

“With these open data efforts there’s always concerns,” Conant said. “Sometimes it’s the effort required to get a particular data set released or ready; some of them are concerns about sensitivity. But overall I get the impression city staff are supportive.”

Fortunately, he adds, there’s a larger movement for local open government efforts to draw on.

“A lot of the concerns with releasing more pubic records have been addressed, one way or another, in other places,” he says. “The current public records law makes a lot of information legally open but due to technical or procedural issues, they’re not able to access all the information they should.

—

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by its readers. If you like our work, donate directly to us on Patreon. Questions? Comments? Email us.