The historian and UNCA professor on African-Americans in WNC, facing the reality of American tragedy and the importance of power and democracy in public spaces

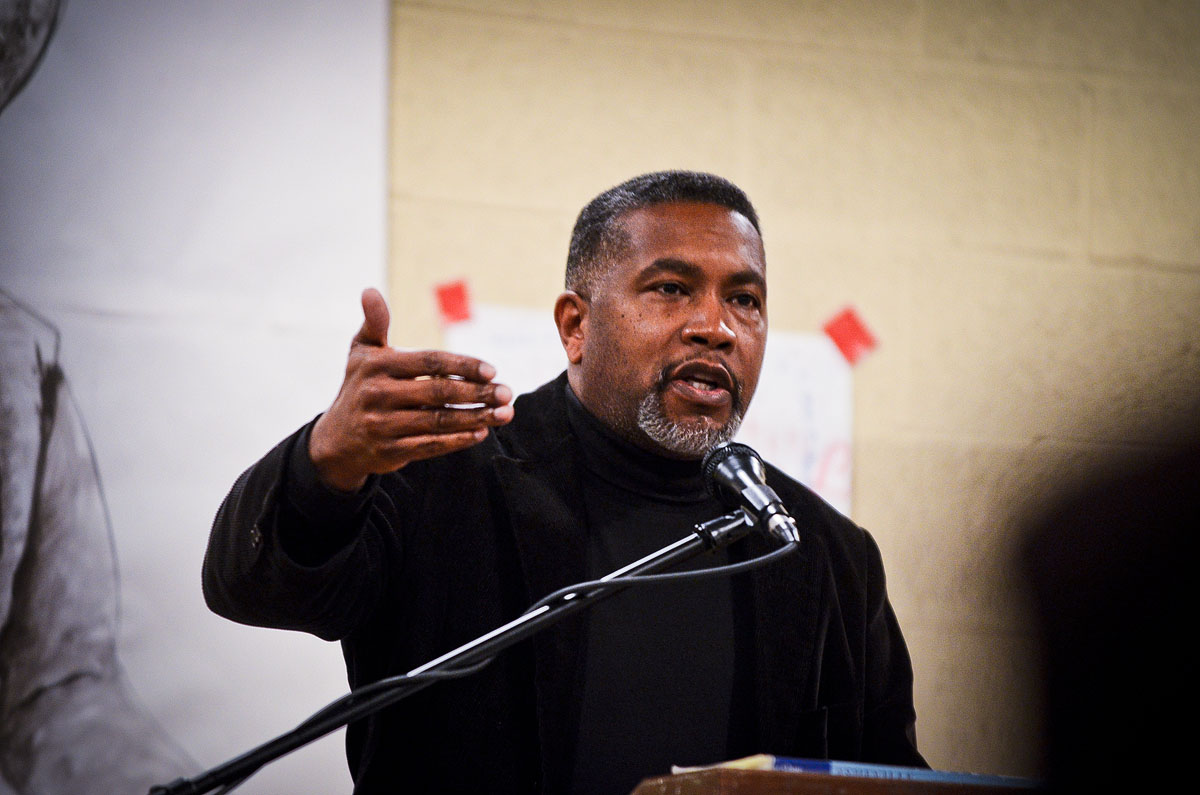

Above: Darin Waters speaking at a Martin Luther King Day event at Kenilworth Presbyterian. Photo by Max Cooper.

From informing Ashevillians about the reality of the area’s history, pushing to change the public square, hosting a radio show, speaking at numerous events and organizing the first African-Americans in WNC history conference last Fall, Darin Waters has shaped the discussion and debates going on throughout our city on multiple fronts.

The UNCA professor, whose family has its own long history in the area, sat down in his office for an interview about the truth of slavery in our region, the tragedies our culture is reluctant to face, the institutions behind social change and the deep ties between Asheville’s past and future.

David Forbes, Asheville Blade: Growing up in Asheville, how did you become interested in history and decide to pursue that?

Darin Waters: I think it had a lot to do with my grandfather, Isaiah Rice. Both my grandfathers, Isaiah Rice and Edgar Waters, Sr. Edgar Waters, my dad’s father, was much older, born in 1897. Obviously, he had seen a lot. I knew him; he didn’t die until 1987. I spent a great deal of time with him, he was born and raised in Edneyville, N.C.

So I would have conversations with him and he would tell me stories about living back over in Henderson County. Then my mother’s grandfather, I would say her whole family, my grandfather Isaiah Rice and my grandmother Geraldine Rice and my great-grandmother Creola Bradley, all together they just had a deep sense of the past, of family. My grandfather, as a hobby, he took photographs, an amateur photography. We’re going to be doing some stuff with the collection of photographs he took later on, which gives a major photographic history of African-Americans history in Asheville.

Special collections has part of the photograph collection here now and they’re digitizing things, but we’re hoping at the Fall conference, when we do African-Americans in Western North Carolina again, in October, we’ll exhibit some of the photographs as a part of that.

From growing up with that, when did you decide that you wanted to go into academia specifically to pursue this interest in history?

When I went to undergrad, and I graduated with my degree, I felt like I wanted to go to law school. In order to get a feel for what the court system was all about I took a job as a probation/parole officer, in Wake County, in Raleigh. I did that job for five years.

While I was doing that, I was also appointed to the city of Raleigh’s Housing Authority, to its board of commissioners, and ended up becoming the chairman of the board of commissioners for a year. So I had my hands in the court stuff and messing with the political side of it with regards to housing.

I think that experience turned me off from either one. I decided that I really had a passion and love for history and then I had a mentor who lived in Washington, D.C. Jay Parker is his name. Through conversations, he steered me towards pursuing my passion for history.

I think it works. When I was a probation officer, especially when I had young people on my caseload, especially younger African-Americans, it seemed like they didn’t have a really good sense of their own identity or who they were. That seemed to be part of the problem that they were having with the legal system, why they were kind of caught up in it. In my opinion history helps to connect you with your past, helps you to kind of connect you with your identity. To tell you the truth I see it as important to people’s outlook.

I feel like, in some ways, while I may be doing academic work, there’s social work involved in it as well.

One thing you’ve mentioned frequently are the myths around African-Americans in this area, especially around slavery and Reconstruction. What is the core of these myths versus the reality?

The core of the myth kind of develops out of people’s assumption that slavery only thrives with a plantation economy. Since you didn’t have large plantations in Western North Carolina, you had small farms, then slavery wasn’t a labor system that you needed. That kind of establishes this idea that Southern Appalachia farmers wouldn’t need slave labor because they weren’t involved in the larger market, they’re kind of disconnected from the market revolution that’s taking place in the early 19th century and then move forward.

But people like John Inscoe have shown in their work that Western North Carolina was very well-connected with the larger markets outside this region, especially in Georgia, South Carolina and even going farther South. Inscoe shows that in his work Mountain Masters.

So while the number of slaves working on farms or plantations is smaller than it is in other areas of the state, there were still some who did. Sarah Gudger is a case in point. We have her story so we know what her experiences were.

Also, people tend to forget that slave labor can be used for almost anything. During the Civil War, there was a manufacturing industry that developed in the South and they had nearly 3,000 slave laborers working to build weapons for the Confederacy.

I say that just to say that slave labor was very diversified in that it was used in the Western region and in Southern Appalachia to do other things besides agriculture, like in mining concerns.

They were used to help build infrastructure, they were especially effective in helping to develop the Buncombe Turnpike and to maintain the turnpike. They’re very active in Western North Carolina — in this case most prominently in Asheville and Henderson County, especially Flat Rock — very prominent in the early tourism industry. This is kind of the second home movement for many Southern planters coming from the lowland regions of the South. So they’re used for that. One of David Lowry Swain’s descendants used his slaves here in Buncombe County to work in a hat factory.

It seems like that contradicts that this was in any way a dying institution

Oh yeah. Gordon McKinney and John Inscoe show that in their book, the Heart of Confederate Appalachia, which looks at the Civil War in Western North Carolina. As does Steven Nash, whose book is coming out soon, they show that as slavery is dying, clearly dying in other areas of the South, it’s expanding in Western North Carolina. People are still buying and selling slaves. You also have a growing slave population because many of the planters in the lowland regions are moving their slaves here to protect them from federal troops who are coming through and might liberate them. So that is expanding the population.

In some of the remarks you made earlier, you mentioned that “the slaves liberated themselves” in many ways. Can you elaborate on that a little bit?

This is an argument that people like, to note one historian in particular, Ira Berlin is making. He has an article he wrote years ago called Who freed the slaves? What he’s showing is that the slaves didn’t wait for an emancipation proclamation. Even when you look at the Emancipation Proclamation itself, Lincoln issues his proclamation on January 1, 1863 but even before then Congress had already passed two major acts that essentially spearheaded emancipation. That had already set the ball rolling in that direction.

Part of the reason Congress is doing this is because many of the slaves did not wait for any official document and are escaping into Union lines, are moving into Union camps. Berlin shows this really well through primary source materials like letters from officers and just general soldiers talking about slaves who were coming into Union camps, who were helping to build trenches, to build fortifications. Slave women, or contraband in this case, are cooking food, they’re helping to take care, mending clothes. These are jobs that soldiers need them to do so that they can continue to fight a battle.

So they begin to complain about this idea that if a master showed up and wanted his contraband back, that they could take them only to be used against them in this war they were fighting. So in many ways by the slaves moving early to free themselves by going into Union lines for protection, they were essentially forcing the federal government to act.

You mentioned earlier the role that history plays in people’s identity, and you’ve certainly been active in helping to inform Asheville about this. What’s the importance of confronting, dealing with, incorporating history into civic life with these kind of issues?

Whether we like to admit it or not, we have a collective public narrative of American history. I’m teaching a Civil War class now and generally as Americans we really like to think of our history as a progressive triumphalist history.

But slavery first — because we look at the whole history of slavery first — and then what comes after it? You’ve got Jim Crow segregation and all the issues that are involved with it. Lynching, segregation, and so on.

The only words you can use for those, for that history, is that it is a rather tragic history. I don’t think we like to face tragedy, as Americans. So we tend to not focus on that story or to say “we’ve solved it. Slavery ended so we don’t discuss it any more.”

I’m not the only one saying this, this is the idea I’m getting from the work of people like Robert Penn Warren, who’s making these statements. In his book Legacy, which looks at the Civil War, he makes the point that the Civil War is important if we are able to embrace even the tragedy of it simply because it, for the first time in our history, finally forced Americans to really become aware of the cost of actually having a history.

But you can only see that cost if you deal with the tragedy, and normally we don’t like to deal with the tragedy. We like to think “well, we solved it so we move on,” we continue to progress towards that kind of triumphalist vision of American history. Slavery does not fit well in that.

As for African-Americans, I think that African-Americans need to remember it, because how we remember and think about our ancestors is important to how we move forward.

I know that kind of gets into spiritual things, but I’m a believer in the concept that Edmund Burke talked about when he said that the world belongs to the living, the dead and those yet to come. There’s a great historical continuity between us and the generation that lives now, while change is necessary, we still need to understand the difficult work that the people who came before us had to do to get us to where we are. We can only understand that by focussing on the past and honoring that so we have something of substance to give to the next generation.

One of the things I’ve heard just in my time in Asheville, which has been about a decade, is this observation that there is an element — not just here, but especially in some ways here — of de facto segregation that’s lingering. Does that reluctance to confront the reality and tragedy of history play a role in preserving that? Specifically, how do you see that playing out in Asheville?

I think so, I think it does. You can just look at our public spaces. One of the things I’ve always heard from people is “where are the African-American people” here in Asheville. But there tends to be a focus on those individual outlying communities, so we tend to identify more with our individual communities like Shiloh, Burton Street, so forth and so on, than we do with our city as a whole.

I think that’s historical. Here one of the challenges, even in the late 19th century, after the Civil War was over — and I talk about this in my dissertation — is that you didn’t have a critical mass in numbers like you did in Eastern North Carolina. There you had the “Black 2nd” which was the Congressional district that elected people like Henry Cheatham and later on George Henry White to Congress, and White would serve in Congress until the disenfranchisement took hold in 1901. You could elect African-Americans to public office there in Eastern North Carolina because you had a more dominant number.

Here, politically, you didn’t have that. I went and did an assessment of the numbers that, with the Republican Party — and the Republican Party is the party that extends suffrage rights to African-Americans after the war through the Reconstruction Acts of 1867 — but in Western North Carolina for the Republican Party to be competitive it didn’t necessarily need black votes.

In the 1890s, the district Western North Carolina was in is represented by a guy named Hamilton Ewart. He is a Republican from this region and he is saying “look, we don’t need to appeal to black voters,” even though the national Republican party is doing that. He’s saying “what we need to be able to do is attract more whites into the party” because, according to my numbers in the 1890s if every black male who was eligible to vote according to what you see in the census data had voted, it amounted to a little over 4,000 as compared to about 38,000 white voters.

So you just do the math about what do you need. I think that means the African-Americans in Western North Carolina, and this may be the case for pretty much all of Southern Appalachia, has to content itself with more of a junior partnership in any type of political coalition that’s formed. You just have to, you don’t have the numbers.

It helps in the development of a more passive political culture, because you can be overwhelmed by numbers. That passivity is a defensive mechanism that develops out of that.

Some people might argue that that’s still around if, historically, that attitude is handed down from generation to generation, and some people argue that it is, then you may see that in some senses even today, that acceptance that this is where we are. It’s a protective mechanism, a defensive stance.

As things proceed into the ’60s and today, are there exceptions to that? How does that proceed in Asheville versus other cities that may have a different make-up or a different culture?

You see it in most every city as you go east of here. One of the things I’m arguing in my work about the development of community life is that there are certain institutions that are really important. Business enterprises are important. One of the most important institutions within the African-American community, as you know and everybody knows, is the church. The church plays a major role.

But I would argue that there’s another, that for Western North Carolina and for Asheville in particular there’s another missing institution that it didn’t have the benefit of, and that’s the benefit of an institution of higher education. There was no historically black college or university that existed here that creates an intellectual class.

I believe an intellectual class is very important and this is an issue that William Chafe raises in his book Civilities and Civil Rights when he looks at the sit-in movement in the ’60s in Greensboro. He raises the question “why did this happen in Greensboro?”

Yes, there were a number of institutions that were important, but a key factor was A&T and Bennett College, which were two historically black colleges and universities. Then Winston-Salem State, Winston-Salem’s African-American community has benefited from that. Greensboro’s African-American community has benefited from A&T and Bennett College. Raleigh has benefitted from the existence, historically, of Shaw University, St. Augustine. In Durham, you had the Negro teaching college, which is now North Carolina Central. Fayetteville had Fayetteville State. Elizabeth City had Elizabeth City State. You’ve got all these institutions. Charlotte you’ve got Johnson C. Smith, you’ve got Barber Scotia, which are all these historically black colleges and universities.

But Asheville never had the benefit of one of those. We can even look west to Atlanta. Atlanta has not only the benefit of the churches of Martin Luther King and his father, you also have Morehouse and Spelman, which are key. The dynamic in those cities were fed and fueled by the role that academics and intellectuals played in forming the community.

It’s interesting that in Asheville ASCORE does emerge out of the schools that were here.

That’s right, it emerges out of Stephens-Lee, which in its history is unique in that the teachers who were at Stephens-Lee in many ways operated like an intellectual class. But I think in many ways that it hurt once that went away.

That’s kind of the dichotomy of all of that. Yes, we wanted integration. There were a number of things gained from integration but a number of things that were lost. The history of Stephens-Lee, I think, is rich because there was a requirement at one time that to be a teacher at Stephens-Lee you had to have a master’s degree and if you didn’t, ultimately, you wouldn’t be teaching there. My parents graduated from Stephens-Lee High School, so it’s no surprise to me.

Nan Chase points this out in her book — she doesn’t say much about it, but she does point it out — that the students who formed ASCORE, it’s the only place in the South where you had sit-in movements being organized where they were led from the very beginning by high school students. In all of those other cities they were led by college students, here it was high school students and those students were essentially challenging the status quo. In many places you’re also having to challenge the status quo in your own community; that plays out in Greensboro. But the difference is in Greensboro, Winston-Salem, Raleigh it’s college students leading it. In Asheville it’s high school students.

You’ve been active in some of the monument efforts, and you’ve spoken about that as a problem from Elizabeth City to Raleigh to here. Where does that kind of blindness in the public square stem from and how, starting in Asheville, do we solve it?

You go back to 1898. There’s an article written by Catherine Bishir, featured in a a book called Where These Memories Grow, and it’s a powerful article entitled “Landmarks of Power.” Jim Stokely and Wilma Dykeman talk about it in their book Neither Black Nor White too, about the solidification of a certain Southern memory.

We can go back prior to the beginning of the Civil War. Jefferson Davis, just a few days before Mississippi secedes from the union, gives a speech about why secession is taking place. He specifically states in there that it is about slavery, that the North would make war on the South because of this issue of slavery. He’s saying it. You can even look in the secession proclamations, that slavery is squarely in the middle of this debate about what this conflict is about.

But after the war is over Jefferson Davis, in his autobiography — this is nearly 1200 pages of an autobiography — goes to great lengths to argue that the war was not about slavery. So you’ve got two Jefferson Davises here.

There are historians who argue that what you see Jefferson Davis doing in his autobiography is beginning to construct, essentially, the Lost Cause narrative of American history, of what the Southern war was about. As that Lost Cause narrative is constructed, the people who are left out of it are African-Americans.

In order to further solidify the Lost Cause narrative, they did it through monuments. Most people aren’t going to get their history, especially after they’re in high school, from a class. But they’re going to get it on a daily basis of what you see around you: the naming of buildings, the naming of streets. It may be subconscious. People don’t think about it, they’re just seeing statues, but that’s a narrative people are getting of American history.

Bishir shows in her article that this was purposeful, it was meant to be that way, it was to project that story into the future. It says to those who have experienced the tragic past of American history, like African-Americans, that while you may be here your story is not the story that matters, your story is not the story that defines what American history is all about. It’s this larger narrative, it’s the narrative that you see in statues, it’s the narrative that you see especially in places of power.

The Vance Monument is in a space of power. Confederate monuments are always found in places of power. By that I mean not only economic power, because you have the banks and major businesses that surround these areas, but you also have the courthouse, you have City Hall that’s right there. You go to any of these cities you know exactly where to find the Confederate monument. Go to the courthouse, it’s going to be right there. It’s a place of power, where the decisions go on. To me it says if you want to know what power is about and the story of the construction of American power, this is the place and this is the story that you see.

How does that myth get changed, broken, replaced in the public square?

By people demanding that the other voices be included.

What would a culture in Asheville that truly incorporated, understood that and broke with that past look like?

First of all, I think in the African-American community it would be an acceptance that one of the first places we need to go as far as our memory is concerned, that we need to remember in any commemoration or statue or monument that is built should be to remember the voiceless, our enslaved ancestors who were bought and sold. They were voiceless and by recognizing and honoring them now, we give voice to people that didn’t have voice at the time. I think that’s part of where our future mental and psychological health is going to come from, by acknowledging that.

You’re going to see a recognition of that, almost like the Jews with the Holocaust. There’s a Holocaust Museum and they remember. Even though the Holocaust did not happen here in the United States, there’s one in the United States.

In this local community our local thoroughfares don’t have African-American names on them. I know we’ve got Martin Luther King . That’s great and fine, but Martin Luther King did not live in Asheville. So who is someone from Asheville that can be honored in a major thoroughfare that is not isolated to an African-American community? That begins to integrate the memory, and statuary begins to integrate the memory.

Does that have the effect of reminding the population in Asheville that’s not African-American that history is not theirs alone?

It does, and to have to reflect upon. We know that. Today in my Civil War class I talked about that we can have these reenactments and things we do today and there can be a lot of camaraderie that goes on at these events. But at the time these things were occurring, they were very painful and real battles and the people who came out of that period, both black and white, were scarred. Deeply.

I can see why there would be some who would say “ok, we don’t want to revisit this in a way that talks about the pain of it all.’ But by dismissing the pain of it you’re dismissing a reality that was the reality of African-Americans and I think that needs to be dealt with.

In that article I did for the Mountain Xpress I use the term ‘democratize America’s collective memory.’ That could look like a very crowded public space, but that what’s democracy is. It’s all of these voices that are there. Recognizing that if we get to a place and have the ability to deal with the tragedy, it helps to convey a message not just to the current generation but to future generations that life is complex and that’s ok.

Does that help make the future more democratic?

I think so.

—

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by its readers. If you like our work, donate directly to us on Patreon. Questions? Comments? Email us.