Whooping cough is making a local comeback. More on this once-defeated disease, why it’s returning and how our society’s frayed

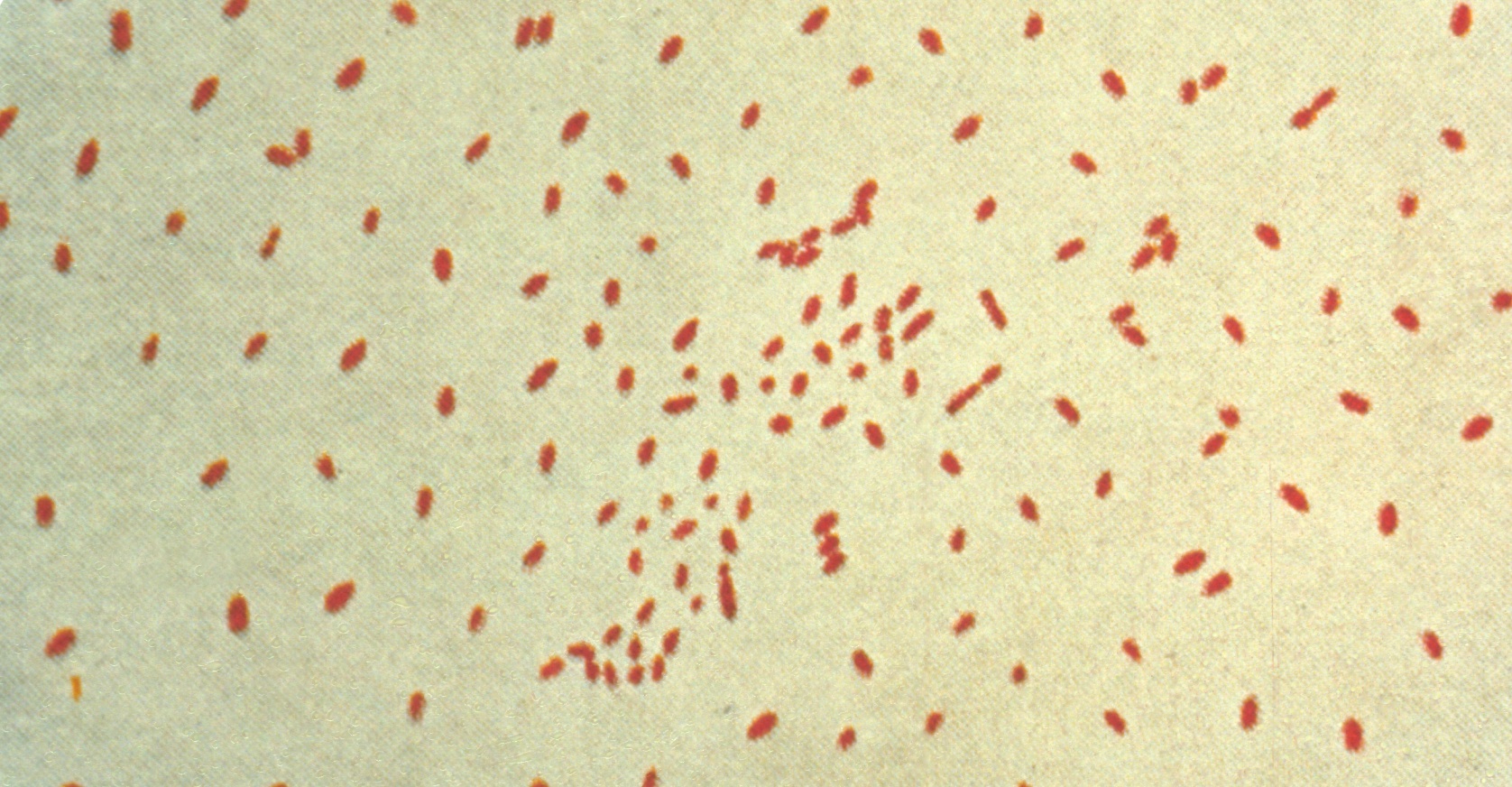

Above: The Bortedella pertussis bacteria that causes whooping cough, image from the Center for Disease Control

Whooping cough is an easy disease to ignore. With its Seussical name and propensity to hit hardest the smallest among us, an outbreak of pertussis doesn’t have quite the media sex appeal of photogenic measles or a collective of rabid raccoons. Of course, whether or not we give a problem our attention has no bearing on whether or not said problem exists: I’m not sure if you’ve noticed, but cases of whooping cough have begun to rise in our mountains. And that’s a problem.

Back in December the Citizen-Times reported on an increase in pertussis in Buncombe County, with a cluster of 19 active cases. And, according to Jan Shepard, the newly-appointed director of the county’s Department of Health and Human Services, the spike in cases is a part of a broader trend. “I would say that overall, and you know I’m not sure I’m being specific to the county, but in our western region we are seeing more cases of pertussis as the years go by.”

To wit, in 2013 Buncombe saw 19 cases of whooping cough; in the following year, there were 60. (When asked about the projected caseload for 2015, Sue Ellen Morrison, the local health department’s Disease Control Lead Nurse, quipped, “We don’t project cases of communicable diseases. Any infection is one too many.”)

The reason for the increase is flagging vaccination rates. “Well, we certainly know that immunization rates correlate with disease outbreaks,” Shepard told the Blade. “Our rate of folks who decline immunization and enter into an exempt status of medical or non-medical reasons is much higher than the state rate.” Five times that of the state rate, in fact. “Then you can suggest that there are pockets of communities within the whole county that no longer have that full protection because of the number of young people and adults who aren’t immunized.”

As someone who reports on infectious disease, it seems to me that the undeniable efficacy of inoculations has been too successful. We — the unwashed masses — have forgotten to be scared of the childhood killers that still lurk amongst us. Whooping cough isn’t just the province of mommy bloggers’ Facebook comment thread wars: it’s a very real disease, with very real consequences. It’s a highly contagious infection, named for the horrible sucking sound that lungs make when trying desperately to find oxygen during a coughing fit. The disease burns away the tiny hairs that brush debris out of your lungs and windpipe; without them, the intense cough lingers. It is a notorious baby killer.

Pertussis is a bacterial infection and, before the advent of vaccines, was one of the leading causes of death in infants. In the 1930s and ’40s, the U.S. saw upwards of 150,000 cases every year, on average. With the development of the vaccine, cases dropped precipitously and quickly, down to a low of just over 1,000 cases in 1976. In 2012, there were 48,277 reported cases of whooping cough in the U.S., the highest numbers seen since 1956.

“Outbreaks do happen when people are not immunized,” said Shepard, discussing the biggest challenges the health department faces in the fight against pertussis. “We’re creating these holes in our shield of protection by having those pockets in the community of folks who aren’t immunized.”

There is a generational effect to be addressed, as well, Shepard notes. “For pertussis in particular there’s an additional concern in that we’re seeing some new mothers and fathers who have infants that aren’t immunized themselves when their babies are born.” This is very dangerous, as infants cannot be immunized until they are two months old. “If the parents and the family members, caregivers and so forth have that shield of protection around them then it does protect the baby. And it is a heartbreaking disease for a baby to contract, so we want to encourage parents to really think about that.”

It’s naive to believe there are no risks inherent in the social construct. Is driving safe? Hell no. A bunch of flawed meatsacks with perception problems wielding great metal destructocons at each other is literally a recipe for disaster. But we want to use cars to get around quickly because we are smart, lazy creatures. So we all agree to follow the rules of the road, even if it means sometimes going slower than you like and sometimes even getting hurt despite following all the rules.

In this way, car accidents are like diseases.

Not so long ago, humans decided that it would be dope as hell to live close together. Think of the time saved commuting! But all that proximity came with a little problem: human beings are disgusting. When we lived separate, a lone sick person was like a drunk good ol’ boy riding his tractor all over the yard; now that we live together, a sick person is more like a bus driver with six martinis in his empty stomach.

But humans like living around each other; we are social creatures, and some of us just require the ability to order take-out twenty-four hours a day. So, we — the people who live around each other — came up with the following two-part social agreement:

1. Don’t crap in public areas.

2. Keep yourself from getting sick so that we can all stay healthy.

Before, when we were isolated, it didn’t matter if Billy Joe’s kid got sick. They were a mile down the road and could keep to themselves. But now we dump all of our babies together in communal child-care and education, those hotbeds of disease where infectious agents can spread like toddler spit on a chew toy.

The risk we take when we drive is that of an accident; we follow the rules of the road to safeguard ourselves, our families, and other drivers. We also follow the rules to protect those at greatest risk: the pedestrians who are not driving.

Similarly, the risk we take by living in large, close groups is that of infections; as such, we wash our hands and poop in secret and vaccinate ourselves to protect the safety of us all, especially those at the greatest risk of infection: the people who, due to medical reasons, cannot receive vaccines. Public health pedestrians, if you will.

“I think the concerned members of the community could help spread the word,” Shepard says, describing how the community can help staunch the flow of pertussis through our children. “[They] could encourage their friends and neighbors and families to talk with their preferred medical professional about immunizations, to just advocate for the importance of protecting the community.”

Others have taken a stricter stance, such as our own Sen. Terry Van Duyn, one of three co-sponsors of the recent state bill to limit vaccine exemptions for religious reasons. But after a backlash from across the state, Van Duyn said she “went too far” and, with her co-sponsors, recently announced that the bill was dead.

Protecting our young from whooping cough, something once so straightforward, is shaping up to be quite the battle.

For Asheville — a place that ostensibly prides itself on its supportive and close-knit community — to eschew vaccinations is antithetical to the cultural values we claim to hold dear. After all, the abstention from inoculations says to your neighbors writ large “I do not care about you.” It says that the tiny chance your own child faces regarding a serious vaccine reaction is worth the illness and death that can and do occur in the absence of immunizations. It says “fuck you, I got mine” in a community we all pretend is a haven for “don’t be that asshole.”

—

Leigh Cowart is a freelance journalist and writer covering science, sports, and sex. Her work has appeared in The Independent, Hazlitt, Vice, The Daily Beast, Buzzfeed News, the Verge, SB Nation and Deadspin, among others. She resides in Asheville.

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by its readers. If you like our work, donate directly to us on Patreon. Questions? Comments? Email us.