Asheville’s current approach to diversity is like putting a bandage on a dirty wound. A better way will require a more politically and economically powerful black community — and the city truly addressing some hard history.

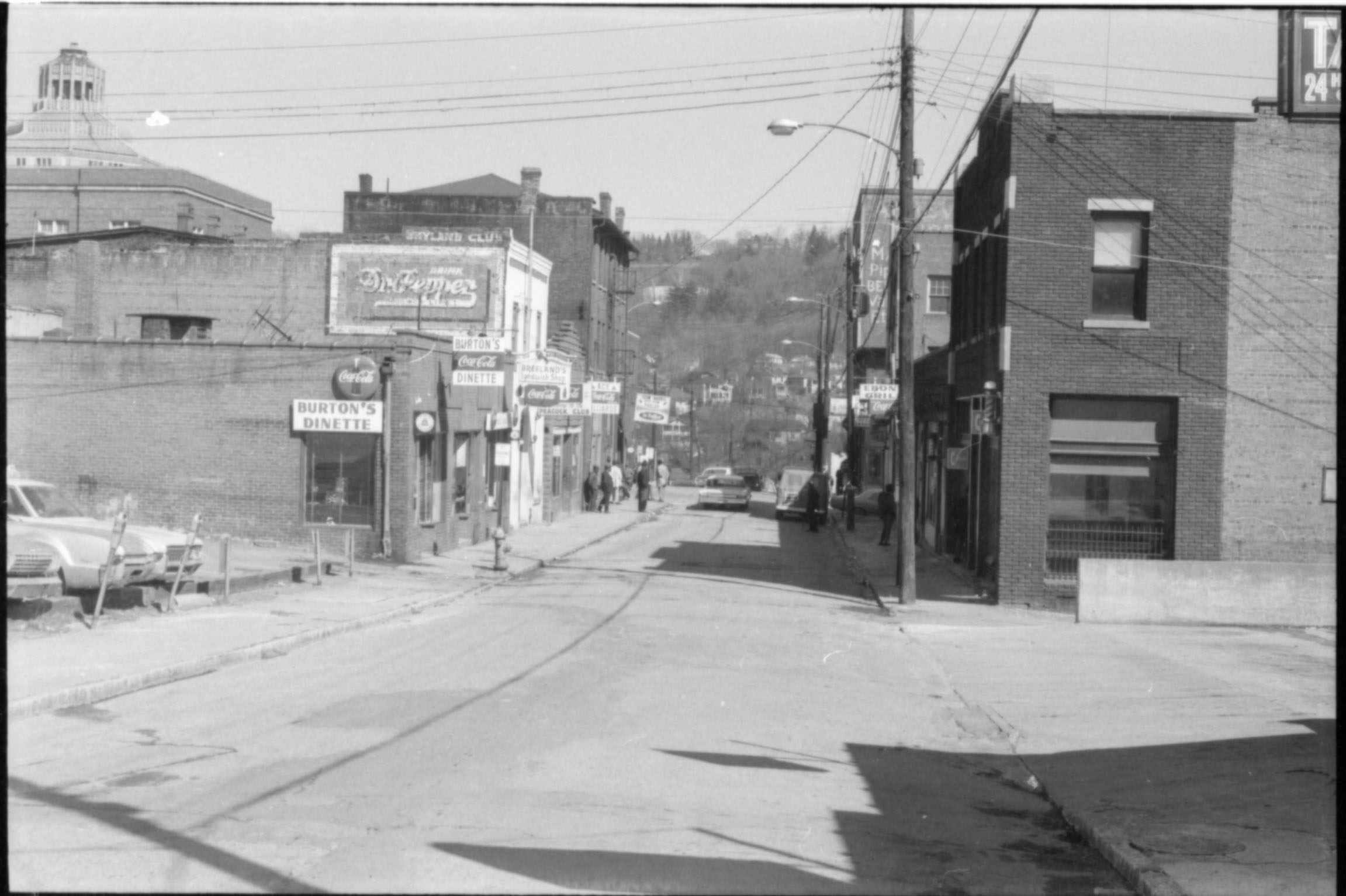

Above: African-American owned businesses in downtown, before the East End neighborhood was devastated by “urban renewal.” North Carolina Collection, Pack Memorial Public Library. Photo from the Andrea Clark Collection.

By Sheneika Smith

Asheville’s supposedly the happiest place in America, but those sentiments aren’t echoed by many people of color who reside here. While tourists clap and gyrate to rhythms around Friday night drum circles, pitching coins and dollars to hippie street performers, one must stop and wonder why there is such a lack of racial integration in downtown Asheville.

Asheville is cited for openness and civility, with tolerance for spirituality and sexuality, but it has failed to mend the strained relations between the government and local blacks following urban renewal (or “urban removal’’ as it is referred to by most who experienced the disintegration of their communities in the 70’s).

Though some blacks in Asheville avoided the crushing effects of this “revitalization” project and fared better than others, none can deny the aftermath. When I talked recently to Hilary Chiz, a transplant from the Mississippi Delta recently, she pointed out that, “like a lot of federally funded programs, there were no real notion of consequence. I don’t think it was intentional to ‘rid the blight.’ The results of laying waste to huge swaths of established neighborhoods was the same all over the country.”

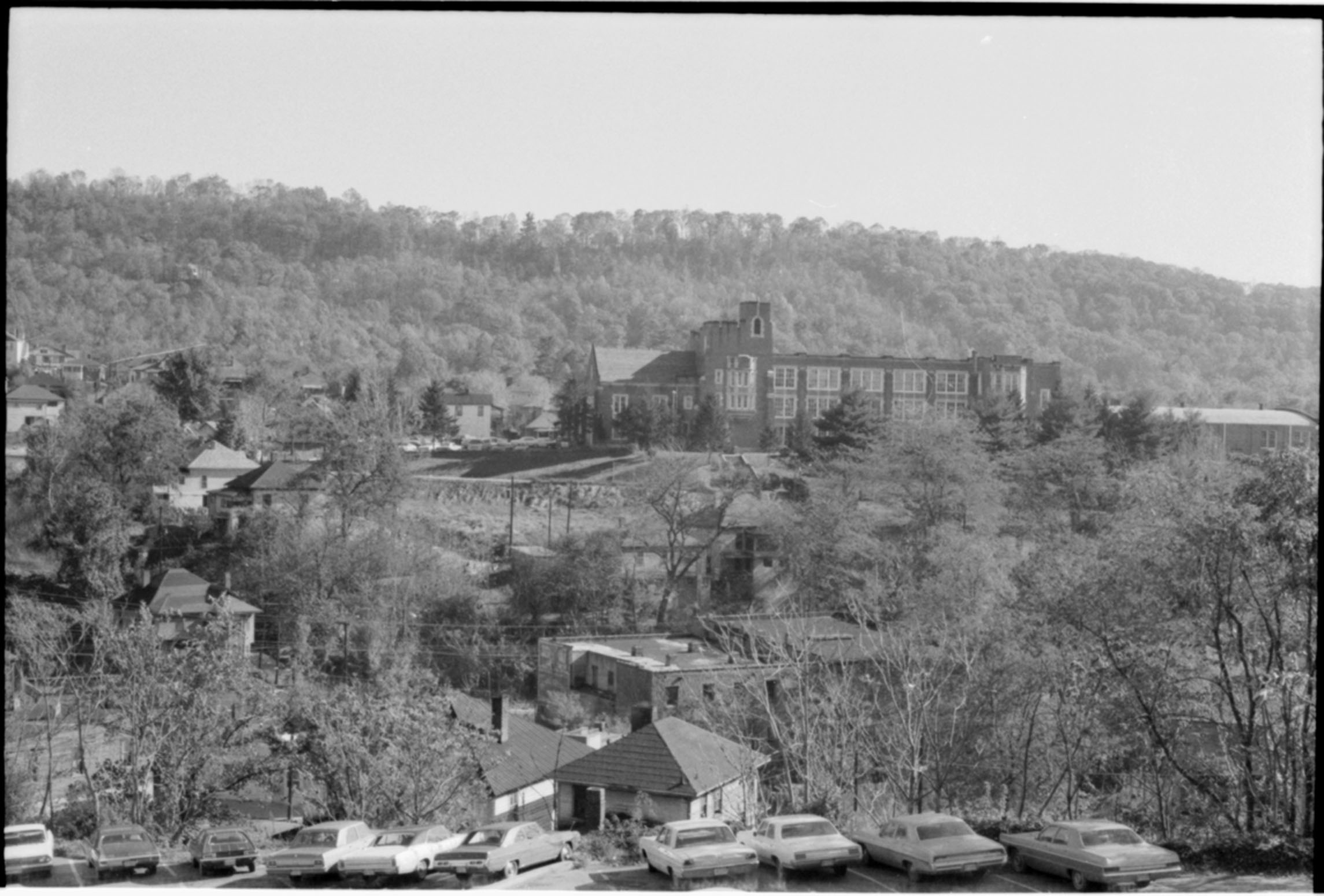

We took a blunt hit in the years leading up to urban renewal too. Stephens-Lee High school was the only high school for blacks in Buncombe County and surrounding areas and was the shared pride of locals both black and white. During integration, rather than staying open as an anchor for the community the “Castle on the Hill” was forced to close its doors. This significant loss displaced several nurturing principals and teachers who not only taught academics, but business development, music, character and positive leadership.

Segregation died, but in the years after the spirit of the community suffered major damage as well. Black-owned businesses already struggled to keep their doors open and their remaining hope was virtually wiped out during urban renewal. Black doctors, dentists and lawyers offices, churches, grocery stores, funeral parlors and theaters were all lost. While others rested in the economic shade of growing tourism, Asheville’s black families lost homes and businesses.

But Asheville appears to have dismissed the crippling impact the years after integration, especially urban renewal, had on the community, questioning why more blacks aren’t engaged. They force-feed minorities initiatives, plans and programs aimed to diversify. Meanwhile music series, festivals and events lock out their input and instead reflect the interest of the majority. Truly diverse environments must feel like home away from home: a place where uniqueness is embraced, where minorities don’t have to put on a mask to become acquaintances. Their perspectives must be beneficial, key parts of the discussion; not just superficial suggestions.

Real diversity is not a matter of simply welcoming “others.” It is about cultivating opportunities where individuals aren’t just seen, but valued and inspired creatively and intellectually. James Lee III, a local black minister and successful businessman, explains that he has challenged organizations that welcome people of color to participant in the program work and management, but exclude them from infrastructural development and decision-making.

The first contribution necessary to cultivate healthy, real representation is authenticity. The way organizations in Asheville usually pursue diversity and inclusion is more like a fad.

Our city’s not alone here: all the major cities flaunt “diversity” like badges of honor. They want to appear socially accepting, but their claims ring hollow in the shadow of urban renewal, even moreso in the face of ongoing gentrification.

No matter how creative and well thought-out these plans are, they’ll fall short, because they weren’t conceptualized with an understanding of the real trauma the black community in Asheville endured. The generations since urban renewal have struggled to plant sustainable businesses and build economic muscle because Asheville has the among highest cost of living and lowest salaries in North Carolina. The only way genuine diversity and inclusion can be achieved is through empowerment.

Stephens-Lee during its “Castle on the Hill” days. North Carolina Collection, Pack Memorial Library. Photo from the Andrea Clark collection.

Empowerment is our savior, not the image of “diversity.” Without power, all these plans for diversity are just placing a bandage on a dirty wound. To overcome and counter years of oppression and marginalization, the black community will need to strengthen its social, human and economic power. When those powers are established then diversity will organically evolve. Individuals and networks within our city’s culture need to engage one another across socio-economic, political and religious lines, to build the social power that any group needs to gain momentum and influence.

Once faith in each other is restored, followed by confidence in our own abilities, the muscle of a powerful, growing network can build real opportunities for economic mobility and ensure that the voices of Asheville’s black community are not ignored.

What good will it do for Asheville if the most driven, intellectual blacks are left broken and isolated among the majority? This city definitely needs a cultural shift, but the paper-thin style of diversity only covers up the problems behind the disparities and grim statistics we now face. Empowerment of minority communities will actually save us; changing a defeated trajectory and old patterns while breaking the chains of systemic racism, disenfranchisement, and social injustices.

By first focusing on building the social power of our culture, we’ll be able to restore faith in our own skill and ability, draw on the potential of collective work and glean important lessons from each other’s intellect and success. There is a certain amount of confidence and surety that comes from building with those who empathize and understand your life journey.

An empowerment initiative can be as simple as forming a focus group of blacks who have direct influence on public policy and governmental decision-making or talking with neighbors to solve problems in their community to as broad as helping launch much-needed archeological projects to honor the hundreds of enslaved people who helped build this mountainous town. Projects that create jobs for blacks and retrace our history while enlightening the public; that’s power.

The images of Asheville’s citizens that we see broadcast across the world create a picture of self-acclaimed “cultural diversity.” One that’s marketed globally. An empowered black community, drawing on its own network and skills, will only strengthen the real sustainability and appeal of “beer city.” The real transformation we need goes beyond simple inclusion, into the preservation of a rich culture with the potential to become a key part of a powerful city — on its own terms.

Sheneika Smith is a writer, minister, single mother, Asheville native and community activist. She recently launched Date My City, a social organization that encourages inclusion and empowerment of the local minority community.

Email questions or comments to ashevilleblade at gmail. If you like our work, support the Asheville Blade directly on Patreon.