For three decades, plans for the Interstate 26 expansion have been driven by dangerous, outdated ideas that will hurt our city. The sky isn’t falling, and it’s time to call the state out

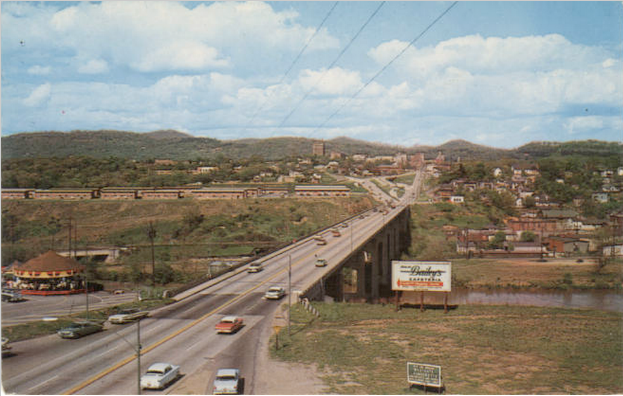

Above: This postcard of the Smokey Park Bridge from the 1960s shows sidewalks on both sides of the bridge with connections on the east side to downtown. They were obliterated by the state in the 1970s and now Asheville is being asked to pay to replace them.

“Two or eight lanes, it don’t matter, it’s just another town.”

– Drive-By Truckers

Chicken Little lives in a world where he believes everyone drives a car. He prioritizes billions of dollars’ worth of road construction projects with for rates of economic return. He promotes bisecting and isolating thriving city neighborhoods with 10-lane highways. He believes the movement of vehicles is more important than the movement of people. Chicken Little constantly complains about not having enough money.

And he’s been telling Asheville the sky is falling for nearly three decades.

Evidence of Mr. Little’s handiwork is evident in the $800 million I-26 Connector project consisting of the widening of I-240 through West Asheville and other projects so it can shed its “Future I-26” moniker.

Chicken Little’s real name is the North Carolina Department of Transportation.

The draft Environmental Impact Statement for the I-26 Connector was published last week with a public hearing set for November 16.

Many community conversations have occurred over this project since North Carolina identified the freeway widening in 1989 as a project that would be funded by the state’s then-new highway trust fund, which was organized to build highway loop routes around cities. November 16 will likely be the final conversation.

It’s easy to see why Asheville leaders were desperate to accept a wider highway in the late 1980s. Downtown was largely a ghost town, still recovering from the shockwaves sent through the community with the exodus of businesses to the suburbs and a proposed downtown shopping mall that would have obliterated nearly a third of downtown.

Today, just as in the 1960s and 1970s, the NCDOT tells us widening highways is the key to economic success. History and a growing collection of economic studies tell us otherwise. The first massive highway building era in and around Asheville was followed by nearly 30 years of economic stagnation. The Crosstown Expressway, Patton Avenue Expressway and NC 191 Expressway were all constructed in this era and combined to form I-240 in the 1970s. This was followed by an extension of the route that blasted through Beaucatcher Mountain to connect to I-40 at Charlotte Highway.

The difference now is Asheville is a marquee “go-to” destination, but $800 million is mobilized for I-26 Connector to treat Asheville as a “go-through” destination.

Asheville has made more progress economically in the past two decades in an era when there were no highway widenings. So why do our leaders continue to listen to the state’s promises of economic vibrancy when the past tells us otherwise? Why do they support the removal of $90 million in private property from the city tax base and 50 businesses at a time when the city has no ability to recoup that land elsewhere?

The region is thriving, downtown is bustling like never before, and formerly tired city neighborhoods are experiencing a renaissance. It took Asheville three decades to recover from the massive economic drain the original highway widening projects resulted in for downtown and city neighborhoods. While other cities across the country are tearing down waterfront freeways, North Carolina is full steam ahead to build one in Asheville. A massive highway expansion doesn’t fit our current trajectory.

DOT’s cross-section (top image) through West Asheville more than doubles the existing footprint of the highway. The photo below it shows what this looks like in real life in Salisbury, NC along I-85.

DOT’s release of the draft Environmental Impact Statement and the upcoming public hearing are just a formality. It’s highly unlikely that much will change in NCDOT’s approach to the project despite nearly three decades of public concern and comment. Attorneys will likely decide its fate.

How can $800 million be bad thing?

We are prohibited from having a real conversation over how $800 million could be better spent on transportation in this region.

After all, as the old adage goes, if they feed us, how can they be bad?

Highway agencies are the modern day manifestation of sophism in its most negative terms. And the public officials who constantly bow to them are just as culpable. After all, how can we turn down $800 million, of which $90 million will be spent to transfer private property to the government? Removing that much taxable value from the city will almost certainly necessitate substantial property tax increases precipitated, in large by part, by the General Assembly prohibiting Asheville from expanding its boundaries to recoup the loss of this property.

In 2014, US Public Interest Research Group identified the proposed to widen I-240 through West Asheville as one of 11 highway boondoggles in the United States. The study showcased that hundreds of millions were proposed to save the average motorist 17 seconds out of a 6.5-minute commute during the p.m. rush hour.

Let that sink in. You save more time when they open a new register while you’re in line at Sam’s Club.

A Career in Modeling

What would happen if projections for social entitlement program recipients never came close to what the government anticipated? Republicans would threaten to de-fund the program and most Democrats would call for some type of investigation.

But when it’s a highway entitlement program, government forecasts are accepted as gospel.

NCDOT and FHWA utilize a tool is called a “travel demand model.” It’s a complicated set of algorithms developed in the 1950s for major metropolitan areas to evaluate how highways perform based on certain traffic and growth assumptions. After nearly three decades of debate about I-26 and the Bowen Bridge, the traffic congestion is still only confined to a short p.m. rush hour period or when there is a crash.

Nearly 40 years-worth of utilizing these models has proven only one thing: the sky doesn’t fall.

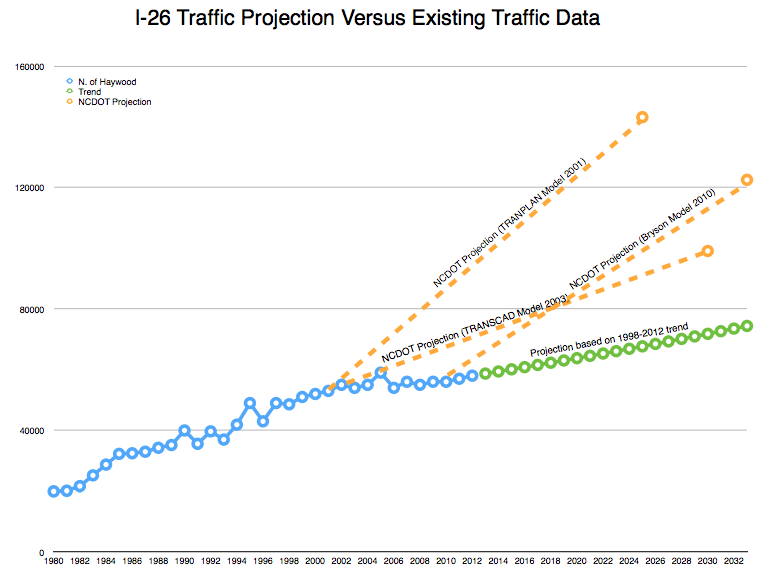

The table below illustrates the lackluster projections from past travel demand models that have all led to DOT stating that the number of lanes proposed through West Asheville was predicated on the outcomes of these models. These were compiled through researching NCDOT traffic counts back to 1980s in addition to travel model projections contained in regional long-range transportation plans adopted by the region since the mid-1970s. (Thanks to Joe Minicozzi from Urban3 for putting them in graphic form to illustrate how poorly the models have predicted Asheville’s traffic).

Past models developed by DOT had forecasts for I-26 through West Asheville that never come close to reality.

The Federal Highway Administration requires the use of these archaic models and scares the public with terms such as “unacceptable congestion” without giving the community the ability to define what is or is not unacceptable. The draft Environmental Impact Statement executive summary says in 2033 that 41 of 80 segments of the project would have these “unacceptable” levels of congestion. Similar past projections said this would occur long before 2033, but it never has.

When FHWA was asked by local leaders to consider fewer lanes on I-240 through West Asheville, their retort was that they require all new interstate highways to be built to standards based on what’s called “level of service” and that the highway performs at a certain level of service 20 years from construction. DOTs would widen a cul-de-sac if the model told them to do it.

These travel demand models, in combination with the design guidelines adopted as gospel by the NCDOT and FHWA, have a much greater impact on the design of cities than even the most stringent zoning ordinance. The model cares nothing about community context, the safety of people, or the long-term economic impacts of removing taxable land via wide swaths of right-of-way. It does not account for the needs of pedestrians, bicyclists or transit users. It cares only about helping us ensure that motorists who don’t yet exist can move without delay 20 years from now.

The draft EIS casts the six-lane option aside from the start. West Asheville never had a chance.

The Cascade Effect

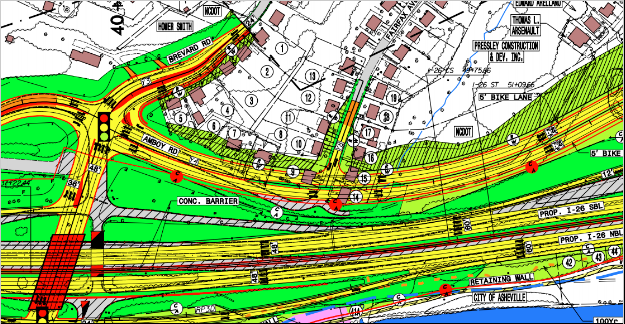

A close examination of NCDOT’s preliminary design drawings for the I-26/240 widening reveals additional cause for concern for West Asheville residents and businesses. Highway engineers will tell us the sky is falling on Amboy Road, Haywood Road, Brevard Road and I-240 through the heart of downtown.

The Amboy Road linkage to I-240 will be altered to become a four-lane highway that connects to Brevard Road near its intersection with Shelburne Road. Two lanes magically necessitate four lanes in NCDOT’s world of highway models. The proposed medians along the route will cut off existing neighborhood bicycling routes and the overall corridor is planned to resemble any other suburban corridor built by NCDOT over the past 50 years.

The design gives no respect to the existing neighborhoods along the route or the context of West Asheville. Fourteen or more homes will be obliterated along near Amboy Road and Brevard Road in a city that is already struggling with a housing shortage. (The draft EIS estimates the lowest number of homes removed to be around 130, in addition to at least 50 businesses.)

Brevard Road will be widened to 6 lanes and then transition to 2 lanes within a few hundred feet of the interchange in West Asheville. Shelburne Road will be 4 lanes west of Brevard Road.

NCDOT’s concept for Amboy Road is a four-lane divided highway (6 lanes at Brevard Road) that cuts off local bike routes and neighborhood circulation routes so it serves an expressway-like function. As proposed, it would remove at least 14 homes in a city already struggling to keep up with housing demand.

A 2004 study of the entire Amboy Road corridor, based on assumptions that I-240/I-26 would be widened per the I-26 Connector revealed NCDOT feels the entire stretch of Amboy Road from I-240 to the French Broad River should be a 4-lane divided highway. NCDOT vaguely acknowledged the Wilma Dykeman Riverway project in their study but said they still stand behind widening Amboy to 4 lanes, a move that would build a community barrier between the riverfront, Carrier Park, Karen Cragnolin Park, Pisgah View Apartments and neighborhoods in West Asheville.

Because of environmental rules, NCDOT’s only option for doing this is widening Amboy Road north of Carrier Park, which would wipe out emerging business and residential development along the route. Any other economic development potential for properties fronting Amboy Road, highlighted by RiverLink in a September 12 email titled “Amboy Road Rebirth,” would be negated. The opportunity for a riverfront district that creates synergies between the park, river and businesses is gone forever if NCDOT plans proceed — all resulting from the cascade effect of the I-26 Connector.

The current Haywood Road interchange is not the prettiest part of West Asheville, but NCDOT’s design concept for the interchange provides motorists with much faster ingress and egress from the main business district of West Asheville. NCDOT’s designs treat Haywood Road just like every other suburban interchange in the state. The curvature of the turns at on- and off-ramp intersections with Haywood Road allow motorists to move at higher rates of speed than they do now while entering and exiting. The Haywood Road footprint is the same as what is proposed at the new Brevard Road and I-26 interchange, at which NCDOT is requiring a design speed of 50 mph.

Higher speeds of traffic and expectations of higher speeds will make it more difficult to cross the overpass on foot or by bike. Families wishing to access the proposed I-26 greenway from West Asheville will have to cross through two interchange intersections where motorists who have expectations of driving faster are less likely to see bicyclists and pedestrians approaching or moving through the interchange given the high speed right turn lanes at the off-ramps.

DOT’s concept for Haywood Road is an interchange with sweeping turning radii that allow motorists to continue at high speeds when entering the West Asheville business district. These higher speeds entice motorist to continue operating at high speeds on a local business street and create safety threats for bicyclists and pedestrians even with new sidewalks and bike lanes. This image, presented to regional leaders in September, illustrates a greenway along the east side, but shows no bicycle lanes along Haywood Road or crosswalks for pedestrians to get across the route.

Getting it Right for Pedestrians & Bicyclists

The draft EIS has some positive language about pedestrian and bicyclist access, stating that the project “would improve both bicycle and pedestrian mobility within the study area through the inclusion of bicycle lanes and sidewalks on many of the cross streets roadways affected by the project.” History tells us we should still proceed with caution.

The original freeways in Asheville disconnected local streets between neighborhoods, walled off public housing, and obliterated the sidewalks that once existed on both sides of the Bowen Bridge. Little of that changes after $800 million in new infrastructure. Based on concepts developed by NCDOT, facilities are present but provide no real connectivity to places that are most likely draw people to use them.

NCDOT created the existing gaps and barriers for pedestrians and bicyclists when it began bisecting the city with expressways. Asheville has correctly asked NCDOT to include features that correct the problems created by NCDOT in the 1960s and 1970s. Unfortunately, NCDOT requires Asheville to pay for what NCDOT terms “incidental” investments due to the state’s antiquated cost-share policies that absolve the state of funding transportation projects for people on foot. No other municipality or agency in the region whose residents will drive through the new highway is asked to put a dime toward the project, but when people other than motorists have needs for basic transportation, the City is on the hook. At minimum, DOT should be required to replace the pedestrian connectivity that once existed on both sides of the bridge before expecting the city to pay to correct deficiencies the state created.

The greenway concept along the east side is a good starting point for restoring some of the barriers brought on by NCDOT’s original highway projects. NCDOT’s concept for the greenway needs substantial work by those who understand how to design facilities for pedestrians and bicyclists, not highway engineers.

With the I-26 Connector, the NCDOT will accommodate dozens of design features for the comfort of motorists to provide them with no delay and little inconvenience. Just a few feet away, pedestrians and bicyclists will be forced into the street if their concepts advance.

Would DOT build an interstate highway that forced motorists onto railroad tracks for a short section? Of course not, but with $800 million in new highly-connected infrastructure designed for the convenience of motorists, DOT’s proposed greenway (green line) would force children and families into the street and across a freeway access road (circled in yellow) to get from West Asheville to downtown across the bridge.

Would NCDOT force motorists to drive on a railroad track for a short segment? That would be absurd. But under the state’s current drawings children and families would leave the protection of the greenway to cross a freeway on-ramp after being forced to walk and ride in the street. Further, NCDOT proposes no connection to the planned Smith Mill Creek greenway identified in the city’s greenway plan and the Burton Street neighborhood community plan.

Getting this right is the least we can do because, in the end, Chicken Little gets his new highway. Asheville gets scratched.

Don Kostelec is an award-winning professional planner, WNC native and safety advocate.

—

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by its readers. If you like our work, donate directly to us on Patreon. Questions? Comments? Email us.