WNC is Sanders territory, local upsets, the repulse of the far-right and more on what the happened in Tuesday’s primaries

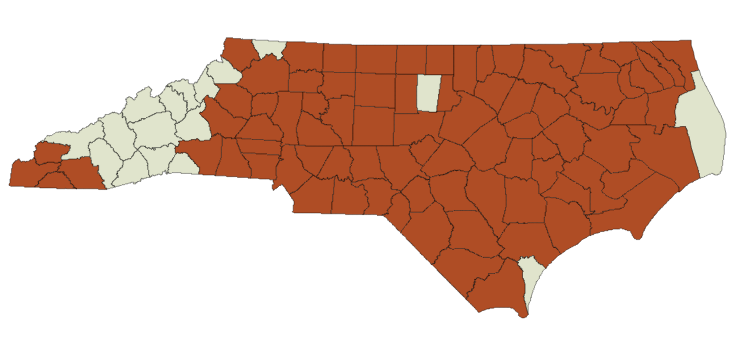

Above: Statewide election results map showing the precincts won by Bernie Sanders in beige and the ones won by Hillary Clinton in red.

With long lines (due to both interest in the Presidential primary and the voter ID mess), campaign season in high gear and debates about the elections everywhere from bars to social media, it was election time. Ashevillians and county residents alike went to early voting sites and polling places to cast their ballots (or try to, anyway).

By the time the results rolled in they were full of interesting results for races both local and national. While the state as a whole went for Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump in the Democratic and Republican nomination primaries, respectively, in Asheville and WNC Bernie Sanders and Ted Cruz did far better. Especially in the case of Sanders, who had one of his best showings in the state in Buncombe County, the results showed a local electorate enthusiastic about his campaign and its message (and plenty of voters still sitting out).

In the other races, commissioner Holly Jones did well in Buncombe and WNC but lost her primary bid for the Democratic nomination for Lt. Governor, incumbent Republicans fended off far-right challengers and the Buncombe commissioners (more on those candidates here) will see their first LGBT member while a local political notable suffered his first campaign defeat.

What’s behind all this and what does it mean? It’s worth a closer look at a primary night with no shortage of resonance both locally and nationally.

Sanders turf — Asheville, Buncombe and WNC as a whole were feeling the Bern. Sanders won 62 percent of the vote across the county and in many Asheville precincts it was even higher. He racked up large numbers in both early voting and on primary day itself.

Sanders’ campaign benefited from enthusiastic local support. Almost as soon as the Vermont Senator announced his run last year, locals began organizing rallies and fundraisers, as Sanders’ messages, especially on economic inequality, found a ready audience in a left-leaning city where many struggle to make ends meet.

In the end, Clinton won two precincts (out of 80) in Buncombe. One was a razor-thin (six votes out of 365) win in the majority African-American Livingston/Southside area. There are, of course, an array of political views and differences among Asheville’s black voters; in this election Clinton had a bit stronger showing here than the rest of the city and the precinct ended up a virtual tie instead of Sanders scoring a rout as in most others.

It’s worth a note that in this election, and any other time, we should beware of simplistic arguments that depict black voters across our city, state and country in a reductive fashion: often they invoke some ugly racism and classism. Those are things sadly not confined to the blatant bigotry on display at Trump rallies. Segregation and the mentalities backing it aren’t dead in our city, including among liberals. Longtime get-out-the-vote organizer David Reid has a detailed breakdown about African-American voter preferences in the Democratic primary that’s worth a read.

Importantly, Clinton won by a larger margin in affluent Biltmore Forest, home to older, wealthier Democrats; a group she’s generally done well with.

Those exceptions aside Sanders rolled (locally, anyway) to victory on a wave of enthusiasm that continued to primary day and gave the social democrat his best showing in a major NC city. Interestingly, WNC as a whole went for Sanders, while in 2008 many of the counties around Asheville went for Clinton during her last run. Remaining union households, colleges and the spread of left-leaning Ashevillians throughout the region due to higher housing costs probably all played a role in that.

But winning a campaign also takes infrastructure — in the form of resources, door-knocking and planning from the central campaign itself to help marshal local dedication and get people to the polls. In NC’s last Democratic presidential primary in 2008, Asheville was hotly contested between the Clinton and Obama campaigns. The latter’s better ground game ended up helping him to victory here (though Clinton won WNC as a whole). This time around, while there were plenty of locals hitting the pavement, the Sanders campaign started late: their campaign headquarters opened up just two weeks before the election, and it was in Swannanoa (not exactly the easiest spot for walk-in volunteers to sign up). While there was a major local groundswell for Sanders, and a lot of locals who put in a lot of work, tactically the central campaign’s approach to areas like WNC (and the state in general) was too little, too late.

Sanders’ campaign needed really high turnout (yes, higher than the wave they got) in bases like Asheville and ground operations that could have had at least a month or two to build support in other parts of the state and cut into Clinton’s leads there. That didn’t happen. While winning NC was always an uphill fight for Sanders, different electoral tactics could have cut into Clinton’s lead far more sharply than they did.

But Clinton supporters — including some of our local politicians who endorsed her — shouldn’t get too comfortable either. Asheville, as we keep highlighting at the Blade, has massive problems with low wages and desperate labor conditions. Clinton, like her or not, is clearly tied with the Democratic establishment and there is a lot of cynicism — especially in cities like ours — about that establishment’s ability or desire to deal with worsening social problems in any serious manner. That’s a fact on the ground, and anyone that thinks it’s going to go away anytime soon is sorely mistaken.

Things are desperate, especially for my generational peers, and it is sometimes too easy for those who spent their careers in a more functional economy or hail from a wealthier background to ignore that reality. Until those problems are seriously addressed, and as long as establishment politicians are perceived as too slow or apathetic towards them, then Sanders’ is far from the last insurgent campaign — from the White House to City Hall — we’ll see.

After all, even in this election year, most local voters still didn’t vote (turnout was at 41 percent). There is, for any future campaign that activate them, a potential wave that can upset all kinds of assumptions about the way things have to go.

The repulse of the far-right — Buncombe, especially Asheville, leans more Democratic, so that primary naturally gets more focus here, but on the Republican end Trump didn’t fare that well around a good chunk of WNC or through the middle of the state (he won NC overall, though fairly narrowly). Cruz won Buncombe, probably boosted by a friendlier perception among business conservatives and evangelicals — two populations strong among GOP voters here.

Locally, the last county commission primaries on the GOP side were a lesson that moderate Republicans were vulnerable to challenges from more conservative candidates: the aggressively anti-tax Miranda DeBruhl defeated commissioner David King in the District 3 (the south and west of the county) primary and went on to fend off a challenge from King’s wife, centrist Nancy Waldrop.

This time, however, DeBruhl herself faced a challenge. While DeBruhl is no centrist and is well known as an proponent of tax cuts and an opponent of the Democratic majority on the commission, Nesbitt is a long-time far-right activist who espoused violent transphobia along with a blatant dislike of the “freaks” in Asheville.

Come election day, DeBruhl won the nomination handily, trouncing Nesbitt with 60 percent of the vote. She’ll have a tougher fight in November against fellow commissioner Brownie Newman, the Democratic nominee, and it will be interesting to see how that races goes: countywide GOP candidates generally face an uphill battle in Presidential election years.

Things were a similar story in the District 2 primary, where incumbent Mike Fryar faced challenger Jordan Burchette. While less flashy than Nesbitt, challenger Jordan Burchette also swore he’d go armed into bathrooms if trans people were allowed and adopted far-right positions. But Fryar fended off the challenge, winning with 57 percent of the vote.

If the last primary showed that center-right candidates were vulnerable in local GOP politics, this one revealed that the far-right had limits in its electoral appeal too.

District 2 showdown — The Democrats also had a contested primary for District 2, encompassing the north and east of the county.

Nancy Nehls Nelson ended up pulling off a victory here among a hard-fought, four-person field. The results on this one were literally all over the map: every candidate won some precincts, and less than a thousand votes separated Nehls Nelson from her next closest competitors, Matt Kern and Larry Dodson.

It’s hard to know what factors are decisive in a close election like that. Nehls Nelson campaigned relentlessly, and despite being significantly out-raised by Dodson and Kern (who also campaigned plenty) in a local election that may prove decisive.

The Democratic field was crowded in the first place because Fryar’s seen as vulnerable in a fairly evenly-divided district. We’ll see: he got more votes than Nehls Nelson in his primary, but he faced one opponent instead of three. If local Democrats have a relatively high turnout this year in District 2, Fryar could be in for a tough race.

Jasmine Beach-Ferrara, third from left, with campaign staff following her March 15 victory in the race for a county commissioners seat. As there are no GOP candidates, her victory in the Democratic primary gives her the position. Photo by Max Cooper.

A new commissioner (and an upset) — One election, however, was already clear by late Tuesday night: Jasmine Beach-Ferrara will become a county commissioner. The first LGBT person to occupy a commissioners’ seat, Beach-Ferrara is the director and founder of the Campaign for Southern Equality, a regional LGBT rights group that’s played a prominent role in a number of protests and legal battles (recently pushing Asheville to adopt Charlotte-style LGBT protections). District 1 contains most of the city of Asheville, and had no Republican candidate this year, so the Democratic primary was decisive.

The field shaped up with three strong candidates, with Beach-Ferrara against Asheville City Council member Gordon Smith and civil rights veteran Isaac Coleman.

Come election night, Smith and Beach-Ferrara proved to be the main competitors for the seat, pulling 39 and 44 percent of the vote, respectively. Notably, the turnout was considerably higher here than the District 2 primaries: Beach-Ferrara racked up about double the votes of Nehls Nelson and Fryar.

It was a highly competitive race when it came to campaigning, both Beach-Ferrara and Smith came in with political networks tied with fundraising and organizing experience.

Beach-Ferrara out-raised Smith, however, pulling in over twice the cash he did ($38,417 to $17,269 at the end of last month) and her organizing experience, along with the networks developed as head of CSE, allowed her to mount a serious citywide campaign.

Smith also campaigned hard, activating the connections he’d built up in over six years on Council (and time before that as a local activist), touted a range of endorsements from local notables and promised to stand up for cash-strapped locals on the issues he’s emphasized throughout his career.

He lost anyway.

That defeat, the first of Smith’s career, makes this race one of the most interesting for its implications for city politics. Smith was a pioneer of a specific approach to municipal electioneering and one that, for about four years, proved pretty successful. While plenty comfortable, Smith didn’t start out with the war chest some wealthier candidates brought to the table. Instead he built up networks, especially with a base in growing West Asheville, compiled a slew of endorsements, focused on consensus over direct conflict and made many, many promises to tackle issues like affordable housing to better wages to sustainability.

For awhile, this be-positive, talk-to-lots-of-people and run-the-resume approach worked (similar tacks were taken by other successful candidates of similar views) and solidified a “progressive” (largely a combination of center-left and centrists) super-majority on Council. Smith sailed to re-election in 2013.

But last year, candidates pursuing Smith-like methods had a harder time of it (though some of those tactics, like building a base and hitting the pavement, will always be useful for candidates of any stripe). Vice Mayor Marc Hunt lost, as did Smith’s close ally Lindsey Simerly. Julie Mayfield, another Smith endorsee, did get a seat, but narrowly.

Part of this vulnerability is the simple fact that many of the conditions Smith has touted his commitment to improving — affordable housing and wages in particular — have all worsened during his tenure in office.

Now, those issues are of course a bit bigger than any single local politician, but it’s a brute fact of electoral politics that if things noticeably worsen while incumbents are in office, especially issues they focus on, voters will like them less and look for someone else to take their place. That may not be fair, and it can result in worse as well as better, but it is — like the desperation of many of Asheville’s citizens — a reality one must face.

Smith still retains plenty of local loyalty; he lost but wasn’t trounced. But now, as District 1 encompasses much of the city, Smith himself is looking vulnerable if he chooses to contest a Council election again and faces a serious opponent.

The basement election — But Smith may not have to contest another Council election at all, as there’s potentially another election looming as well, though it’s not one most of us will have any say in.

If Newman wins the race for chair of the county commissioners, he’ll vacate his current seat. As commissioners are a partisan office, and Newman’s a Democrat, the local Democratic Party representing the precincts in District 1 will meet to choose his successor.

For that “basement election,” both Smith and Coleman (who sits on the party’s executive committee) are strongly placed.

If Smith prevailed, it would open up his seat on Council. As City Council is nonpartisan, his colleagues would choose his successor to fill out the remaining year of his term. This situation has happened a few times before, and Council has gone for every approach from appointing the next-highest vote-getter from the last election (that would be Rich Lee, in this case) to holding an open application process. Legally, they can appoint anyone they wish as long as they’d normally be eligible for the office.

However, that shakes out, it means that Tuesday night’s results could have an impact in local politics stretching far beyond a single commissioner’s seat.

—

Lastly, a message to everyone who showed up in this primary, especially for the first time: thank you, with the snarl of the new voting restrictions, it’s worth a note of appreciation to your desire to navigate a sometimes-daunting system to make your voice heard.

Now, there remains a lot of work to do, and most of politics doesn’t happen at the polling booth — vital as elections are. I want to see you in picket lines fighting low pay, fighting to end our city’s segregation, standing up for our LGBT and immigrant peers and more. We need your strength, and there is a long, long road ahead.

—

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by its readers. If you like what we do, donate directly to us on Patreon or make a one-time gift to support our work. Questions? Comments? Email us.