A state legislator’s trying to drastically gerrymander Asheville’s city elections. Here’s why that push matters, and where it comes from

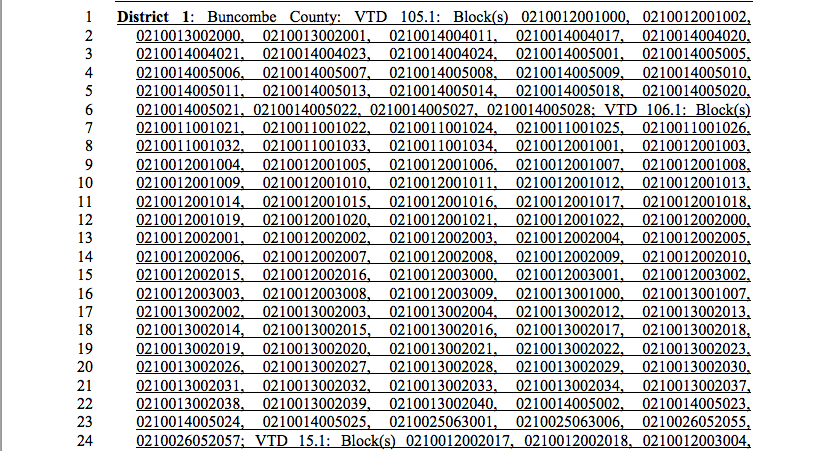

Above: A list of census blocks making up the proposed Council districts in state legislation that would force Asheville to switch to a district system.

On June 22, state Sen. Tom Apodaca filed a bill to impose district elections on Asheville City Council. Right now, every two years voters around the city can vote for three Council members, and every four years they vote for the mayor’s seat too. That system is known as “at-large.” Apodaca’s bill would shift Asheville’s local elections to an entirely opposite system, carving the city into six districts drawn by the state and requiring each candidate to only be elected by voters living in their district (the mayor would still be elected by the whole city).

Perhaps not surprisingly for a legislature that’s taken the gerrymandering of their Democratic predecessors to new extremes, it bears all the hallmarks of districts drawn to select voters and punish opposition candidates. The districts hack up different parts of Asheville (downtown, for example, is divided between three different districts) and places current Council members together to force them to either drop out from running for re-election or run against each other once the bill goes into effect in 2019.

As part of filing the bill, Apodaca signed a statement that no public hearings are necessary, that the bill’s topic is non-controversial and that the other legislators representing Asheville in both the House and Senate support the measure. The first statement is one of absolute contempt for any actual debate about a major change to local elections, the other two are outright false: the matter is incredibly controversial and the entirety of the rest of the local delegation is opposed to it.

If you feel like making your feelings about this known to your legislators, the handy North Carolina Digital Megaphone tool, designed by local open government activists, allows you to email all your state senators and representatives.

Splitting Asheville into districts isn’t an entirely new idea, another state legislator drafted a similar bill three years ago, though it was never filed. The past decade has seen local conservatives go from serious contenders in local government to largely shut out as Asheville’s political spectrum has shifted considerably leftward (though not entirely left-wing). While it’s seen no shortage of wrangling over changes to the local electoral system (including a failed attempt by local Democrats to change the elections), the idea of state-imposed districts has come from conservatives, and it doubtlessly looks more appealing given the trouncing local conservatives received in last year’s Council elections. A similar move in 2011 took the Buncombe County Commissioners from an all-Democratic board to one where the Dems had a 4-3 majority.

Here’s the story of an idea, a backlash, and a local political faction that’s increasingly relied on state fiat — rather than organization and adaptation — to try to cling to a measure of power in an area where its prospects are otherwise dwindling.

The district idea

Districts are one of the election methods allowed under state law, as is the current “at-large” method Asheville uses. Most of NC’s largest cities use some combination of both electing some members at large and others by district. There’s also a hybrid, “district at-large,” where candidates have to live in a given district but are chosen by voters city-wide.

As for which one’s better, that’s a matter of major debate. Defenders of the at-large system say it works well for small and medium-size cities and helps ensure that elected officials are looking out for the interests of the city as a whole rather than just their own backyard. Proponents of district systems assert that they ensure no part of the city is left out, and can help with minority representation.

My hometown of Elizabeth City, a place a good deal smaller than Asheville, offers an interesting — and contrasting — case of a change to district elections mandated by an outside government. There, a ward system — with two Council members for each district — was put in place by federal officials in the late ’80s because the previous at-large system dispersed African-American votes and helped preserve segregation. There the NAACP and more left-leaning activists and officials supported the ward system, while conservatives generally opposed it and favored the older at-large method.

In cities where mostly minority residents are concentrated in a given area, district elections can ensure their representation, while at-large systems can lessen their voting power.

However, Asheville offers a very different case. Here, instead of being concentrated in one part of the city, the African-American population is concentrated in neighborhoods (Shiloh, Burton Street, Southside) spread throughout. Right now, if mobilized behind a candidate (or slate of candidates) that voting bloc that can prove decisive in local elections because its combined numbers are enough to swing an at-large election (there’s a good argument it did just that last year). However, if split among several districts, that same impact diminishes.

That factor, and many others, are the sort of thing locals could debate, if they’re given the opportunity.

Changing ground and electoral wrangling

In Asheville, to understand the debates over local electoral systems, it’s important to turn to the northern part of the city. Affluent areas like Montford and Kimberly Avenue have produced a large number of Council members. From 1995 to 2013, over half of the city’s elected officials came from this part of town.

The predominance of North Ashevillians in local government was, for a long time, more a matter of wealth than ideology. Both conservative and liberal candidates tended to come from this area because cash and established political networks are helpful for candidates of any stripe, especially in lower-turnout local elections.

That fact didn’t go unnoticed, though a shift to district elections wasn’t the immediate idea to solve it. Bryan Freeborn ran for Council in 2005 (and ended up getting a seat) partly asserting that West Asheville was under-represented. That same year Chris Pelly (who didn’t), claimed the same about East Asheville’s interests in his second run for a spot in City Hall (Pelly would later gain a seat, again emphasizing the lack of East Asheville representation, in 2011).

That same year Terry Bellamy won the mayor’s seat, defeating fellow Council member Joe Dunn. That year’s elections took place in a period where conservatives and progressives still traded control pretty frequently. Dunn, along with fellow Republican Carl Mumpower and conservative Democrats Charles Worley and Jan Davis, had formed a right-leaning majority on Council for two years. But that year Dunn was out and Worley didn’t make it past the primary. While Mumpower won re-election, it gave progressives (roughly an alliance between the center-left, some centrists and some left-wing types) a solid majority.

During this era the first major attempt to change the city’s electoral system came from progressive Democrats, who voted in 2007 to change Asheville to a partisan election system. That backfired badly; a widespread and bipartisan backlash rallied under the name Let Asheville Vote. Because Council’s attempt to change local elections came from the municipal level, not the state, locals had the option of petitioning to repeal it. They gained the necessary signatures to put it to a referendum in that year’s elections, and the voters overwhelmingly rejected the change.

That election saw the conservatives make some gains. Mumpower was still on Council, Davis won re-election in a landslide — partly because of his opposition to partisan elections — and Republican Bill Russell narrowly defeated Freeborn.

The next year Buncombe County Commissioners Chair Nathan Ramsey, the board’s sole Republican member, proposed a referendum on district elections for the commissioners, but failed to get any support from his Democratic colleagues. Ramsey was defeated by David Gantt that year, but would later serve two years, from 2013 to 2014, as a state legislator.

On the Council front conservative fortunes also dwindled. In 2009, Mumpower lost another bid for re-election decisively. In 2010 Russell ended the GOP’s presence in City Hall when he changed his registration to unaffiliated, citing his distaste for “antics” at a time when the local and state parties were moving farther right. He would later vocally oppose moves by the state legislature such as the attempt to seize Asheville’s water system (something Mumpower opposed as well).

But if Democrats were riding high in local politics, some shocks were on the way. In 2010 Republicans swept the state legislature for the first time in over a century and promptly redrew congressional and general assembly districts heavily in their favor (the federal courts would later rule the congressional maps unconstitutional, some of the state legislature districts are still the topic of another federal lawsuit).

A redraw ended up happening locally too, as then-state Rep. Tim Moffitt pushed through a 2011 overhaul of county elections, replacing the at-large system with two commissioners elected from three districts drawn on the same lines as the state house districts.

On the city front conservatives faced harsher terrain as Republican Mark Cates lost badly in the general election the same year and Davis — a good deal more moderate than Mumpower — barely won another term.

But in 2012, as the district system went into effect for county elections, Republicans came within a hair’s breadth of gaining a majority on the Buncombe Commissioners, as Democrat Ellen Frost only won her commissioner’s seat on a recount.

In 2013, Moffitt’s election-changing plans turned to Asheville. At that point district elections had popped up in the occasional candidate questionnaire and discussion, but hadn’t gained much local traction. That summer he drafted up a plan to change Council elections to five district seats (with districts drawn by Council but subject to state approval), one at-large seat and the mayor elected citywide. At the time, he dismissed any idea of a referendum by asserting that “we’re not a referendum state,” though state law does allow changing local elections systems by referendum or rejecting such a change, as in the case of Asheville’s 2007 partisan election vote. Moffitt never filed the bill, and the next year both he and Ramsey were defeated.

However, the legislature did try to overhaul elections in another city. Last year, the state legislature redrew districts for Greensboro City Council, packing incumbents together there as well and forbidding the city from changing the districts, though a federal judge quickly ruled the plan unconstitutional. State legislators later modified it by taking out some of the most controversial provisions, but the final decision about the city’s districts is up in the air.

That same year local conservatives fielded and backed three candidates, including Mumpower, in Council elections. They promised, in candidate John Miall’s words, to “take our city back.”

They lost badly. None made it out of the primary and while the election showed no lack of dissatisfaction with current Council members and their allies on a number of fronts, that sentiment went in favor of other progressives critical of Council. The November election marked a decade since the 2005 vote that, in retrospect, was the beginning of the Ashevillian right wing’s long electoral decline. In that time the North Asheville lock on Council seats had also lessened a bit, with candidates from other parts of the city faring better in local elections than before.

That’s the context — 10 years of conservative defeat in Asheville — Apodaca’s plan emerges in.

Block by block gerrymander

Changing the political make-up of Council will be a tougher haul than the county, where conservatives have more number and organization in some areas. Asheville’s a pretty left-leaning place no matter how you slice it. But given their relative success at the county level, it’s understandable why local conservatives can see the state changing Council’s whole election system as their best chance.

But the resort to state fiat also indicates a faction seeking to prop up its fortunes rather than figure out a better strategy. Without the fallback of an outgoing state senator essentially rewriting city elections from Raleigh, local conservatives might have to adapt to a changing Asheville.

They might have to figure out appeals that actually resonate with Ashevillians today, or stumble upon the stunningly obvious insight that running candidates who compare the LGBT pride flag to the Nazi flag is a really bad idea.

Advocates of district elections could also have plotted a local route forward. It’s not like a plan for district elections would automatically be without local electoral traction; the predominance of well-off North Ashevillians in Council seats has attracted plenty of ire across the local political spectrum over the years. Covering the back-and-forth of city politics during the last decade there was more than one point where district election advocates would have had a sympathetic hearing and perhaps — if the districts were perceived as fair and drawn according to the wishes of citizens without the ear of a state legislator — even won.

That hasn’t happened. Ironically, the resorts to state intervention both in 2013 and this year have actually bolstered support for the current system among locals who were previously lukewarm about it.

That shouldn’t come as a surprise. The lesson of the original “Let Asheville Vote” was that locals, whatever their views about Council, widely resented an attempt to rewrite their elections without their say-so. In that case the attempt came from progressive Democrats, but plenty of progressives played a part in the overwhelming majority that rejected the partisan election plan.

Instead, the progressive faction on Council had to look to better organizing and more active campaigns to try and secure its position. Whatever one thinks of their views, the approach clearly worked. Ironically the rejection of their attempt to change the election rules ended up forcing them to build a stronger base.

But the city’s right wing have instead given up any tactic but “cry to Raleigh and hope for a gerrymander.” This bill is Apodaca’s swan song. After a decade of long decline, it might prove to be that of Asheville’s conservatives as well.

—

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by its readers. If you like what we do, donate directly to us on Patreon or make a one-time gift to support our work. Questions? Comments? Email us.