The rising use of credit checks, just to allow one to rent housing in Asheville, excludes much of its working class and increasingly pushes them out of the city they make possible

There was an important point raised in the Asheville Citizen-Times‘ June 30 forum on family homelessness, and one that hasn’t gotten the ensuing discussion it deserves.

A panel, composed of both members of the families featured in the paper’s five-part series and non-profit and government staff, talked about the changes most needed to halt a sharp spike in family homelessness.

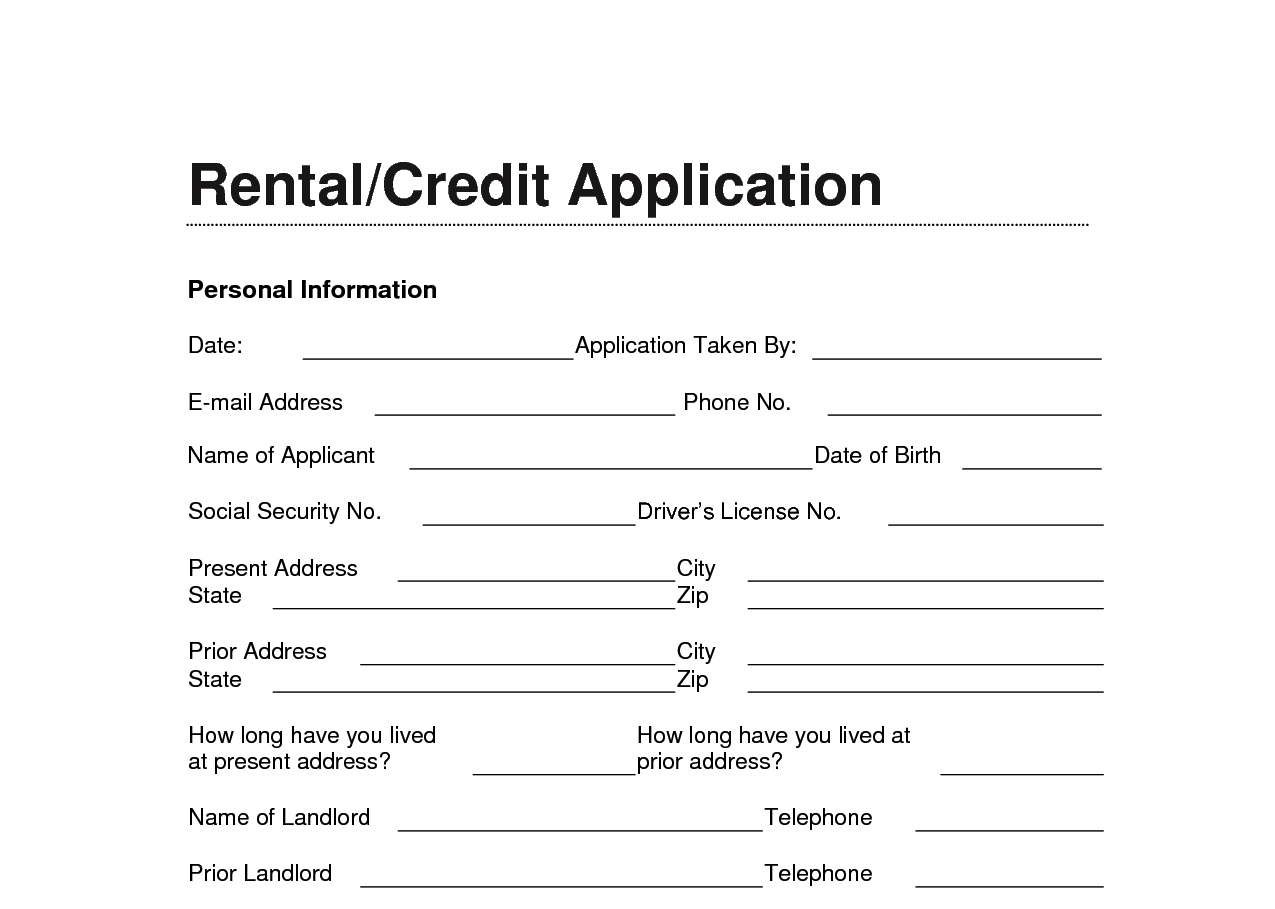

“We’ve got to figure out how to build affordable housing that does not require credit or background checks to get in,” Heather Dillashaw, who heads the Asheville-Buncombe Homeless Initiative, said. “There is no homeless family that I have ever met who has clean credit, because they’ve done everything possible to stay in housing and one late utility bill gets you bad credit. Every management company in town does a credit check.”

The line drew applause. Shane Hopkins, a single father with three children who’s fought homelessness, made the same point, noting that the barrier of credit check made it harder for him to get housing even when he could have afforded to pay.

“Even if you don’t have a criminal record, credit can give a landlord a reason to reject you if you’ve ever had a problem,” he said.

Afterwards I asked Dillashaw something that had been on my mind throughout: for each local family tackling homelessness, how many more were just a paycheck away from ending up in the same situation?

“It’s impossible to measure,” she said. “But it’s a lot.”

Gentrification and its related issues are, rightly, the talk of the day in Asheville. The city’s just wrapped up a study on alternatives to gentrification in the Southside/East of the Riverway area, service workers are organizing against low wages in a supposedly booming town, and our daily newspaper is running stories on rising family homelessness. In fact, the Citizen-Times forum was held in the same building — the Grant Center — where just a few days earlier city staff and consultants announced some of the basic findings of the gentrification study.

It’s easy to think of gentrification as just a process and it is, if one can afford it. But it also pushes and excludes, making affordable neighborhoods unaffordable for those who live there and, eventually, even turning former homes into hostile territory.

Sometimes the process is particularly aggressive, which is why it’s important to focus on credit checks.

For some personal context, I moved to Asheville in mid-2005. From then until early 2008, I lived in three different houses, each with roommates: in West Asheville near Burton Street, in Haw Creek and in Montford.

We dealt with both management companies and individual landlords; none of us ever had to go through a credit check. The Montford landlord conducted a background check, but mainly wanted to make sure we didn’t have violent felonies. I was asked for references to vouch for me, and I provided them. That seemed to be enough.

Making ends meet was hard, sometimes incredibly so. But the city was, as a whole, far more affordable than now. Studies back this up; 2005-07 was one of the last times when Asheville had an ok — not great, but ok – supply of affordable housing.

In 2008, when I moved into my current apartment in downtown, I had to apply with one of the largest management companies in the city, and there was a credit check. I was worried. At that point I’d managed to scrape by doing a combination of freelance work and part-time jobs, and had just been hired at a full-time reporting job. My credit history, on paper, did not look particularly good. But they mostly seemed concerned that I’d never messed up anything severely with previous landlords or missed rent (which I hadn’t). I got into the apartment without issue.

I was lucky, times were changing, or both. In the years since, almost everyone I’ve known or encountered that’s had to deal with rental housing has had to meet a credit check, unless they’ve rented the place under the table. Recently, I’ve had people tell me it’s become far stricter over the years: companies want letters from employers and more just to give someone a chance of getting approved for a basic efficiency.

It’s safe to say that the practice has increased as the cost of housing has skyrocketed. As pointed out in the forum, using strict credit checks already excludes anyone who’s had a bad period in their life, even if it wasn’t something they could have controlled.

But it goes even further: credit checks for housing aren’t just exclusionary, they’re also not particularly accurate. A lot of working class people who’ve juggled paying their other bills or haggled with the phone company — things that can show up as a negative on a credit check — have never missed a month of rent or been evicted. Credits checks also don’t look particularly favorably on people patching together several part-time jobs or freelancing; which also leaves out a lot of Ashevillians.

Then there are people who don’t have a credit rating at all. This is actually a byproduct of being wise. If one is low-income or working class, the credit economy can be incredibly predatory, so staying out of it is often a really good idea. But while this population has done everything they’re “supposed” to — living within their means and avoiding debt — it actually makes them far less likely to get housing if a credit check is used.

So, with all those populations increasingly removed from consideration for rental, who does this situation leave? It leaves people with a well-off co-signer or with enough income or wealth to navigate the loftier parts of the credit economy, where things are more romper room than snakepit. It leaves people likely to not bat an eye or complain if, for example, rent sharply increases the next year.

It leaves, in short, the gentry.

Remember, we’re not talking about loaning someone money for a car or some similar item. We’re not even talking about people’s ability to pay rising rents, though that’s a real issue in its own right.

We’re talking about the use of credit checks to even give people a chance to pay for housing, something incredibly basic to living a non-destitute life. The pervasiveness of credit checks tends to push people excluded by them to rent under the table, leaving them in a more precarious situation with even fewer protections.

So when talking about gentrification and housing in Asheville, it’s important to face the fact that in many cases, there’s already a sign up that reads “gentry only.”

—

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by its readers. If you like our work, support us directly on Patreon. Questions? Comments? Email us.