Racist government programs shaped Asheville’s ‘urban renewal,’ demolishing homes and pushing out thousands. The results still haunt the city today.

Above: Priscilla Ndiaye, with her map of the homes demolished in the Southside neighborhood during urban renewal. She’s standing on the site of the house her family lived in, condemned when she was nine. Photo by Max Cooper.

Priscilla Ndiaye was a child in 1970, when thousands of residents of the Southside neighborhood moved their belongings, many by hand, from their homes.

“I still remember dragging the chairs.”

Ndiaye, who’s served as a chair of the Southside Community Advisory Board and researched the area’s history extensively, was nine when the home her family rented was condemned as part of a sweeping “urban renewal” program.

From the 1950s through the 1970s, urban renewal was vigorously pursued in Asheville and cities around the country, aiming to end “blighted” neighborhoods by demolishing homes and local businesses, with promises that things would improve as a result. During these years, housing projects sprung up around Asheville, and many of those displaced by urban renewal ended up there.

Over 1200 homes and businesses in the Southside area where Ndiaye grew up were demolished. Through the decades of urban renewal, highways cut through close-knit neighborhoods on Burton and Hill Street. The East End, a linchpin of local downtown business and homes, was similarly struck (today, a major part of it is the city’s public works building). For detailed accounts of the program’s impact locally, this 2010 issue of Crossroads, from the North Carolina Humanities Council, is essential reading.

While its course was a complicated one, today Asheville’s urban renewal is generally acknowledged as devastating for many involved, especially the city’s African-American population. When the program is referred to in local political discussion today, it’s usually as a wrong to be righted. Asheville City Council justified spending millions on an affordable housing development in Eagle Market street, for example, as a way to start correcting a historic tragedy.

But the history of urban renewal runs far deeper than the bad decisions or misguided urban theories of mid-20th century planners. It was shaped by a 1930s federal program that helped set bigotry into the structure of housing for decades to come, by setting up maps defining desirable areas for investment. If a neighborhood was considered unsuited for investment it was shaded red — or “redlined.”

The criteria these maps used were often blatantly racist, considering neighborhoods risky for little other reason than having a high percentage of minority — especially African-American or Latino — populations. Those living in the redlined areas were often cut off from mortgage loans, or could only get them at exorbitant rates.

Now, a mapping project shines some light on the overlap between these two programs and how their impacts struck Asheville, due to Ndiaye’s extensive research.

Richard Marciano, a professor of information studies at the University of Maryland, formerly of UNC, has worked for years to chart the effects of redlining around the country with the Mapping Inequality project.

Over two years, he cooperated closely with Ndiaye to trace the links between, and impacts of, redlining and urban renewal locally. The project was recently featured in an episode of The State of Things, and Ndiaye’s efforts in Asheville specifically cited as revealing how the impacts of these programs continue to shape cities today. One of the latest versions of the maps includes detailed information for both Asheville and Durham.

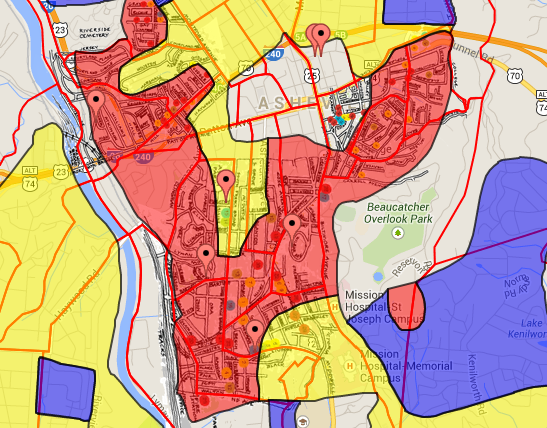

When one overlays the maps of the Asheville neighborhoods targeted for urban renewal and those redlined in the 1930s due to their African-American populations, Marciano notes, “it fits like a glove.”

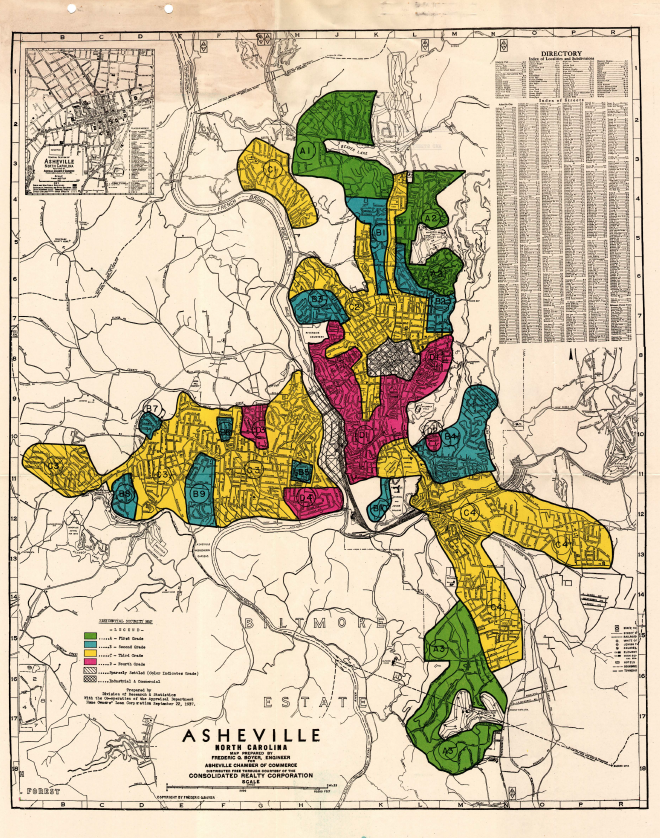

The 1937 HOLC map of Asheville. All but one of the areas marked in red were majority African-American. Image via Mapping Inequality.

‘Detrimental influences’

“Southern side contains railroad depot, big negro business district, and cheap houses,” — description of Southside and East End neighborhoods, from 1937 HOLC appraisals. The area was “redlined” as unsafe for investment or loans to local homeowners.

HOLC, or the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, came into being as one of the many New Deal programs intended to stop the spiral of the Great Depression. To that end, the government-sponsored company handed out millions to save underwater homeowners and refinanced mortgages.

But like many New Deal programs, it had a dark side when it came to racial discrimination. HOLC was also charged with appraising areas, dividing up cities into zones fit for loans and assistance and those that weren’t, ranking neighborhoods by “favorable” and “detrimental” influences. This didn’t just happen in large metropoli; smaller cities like Asheville were also targeted by HOLC’s maps.

One of the driving forces behind HOLC was Homer Hoyt, who became the Federal Housing Administration’s chief economist in 1934 and set up the criteria HOLC would use for its appraisals. Hoyt was a believer in the ability of “scientific” analysis to decide which neighborhoods were worth backing and which weren’t.

Shaped by Hoyt’s guidance, the federal program separated cities into four types of neighborhood, shaded different colors on HOLC’s maps. The districts believed safest were marked green, those not quite as “secure” but still useful blue and declining neighborhoods yellow. Those considered absolutely unsafe for investment were shaded red, or, as the term later arose, “redlined.”

In 2010, Baltimore Sun reporter Antero Pietila extensively documented the effect of redlining on his own city in the book Not in My Neighborhood. He delved into the theories and work of Hoyt and other related economists who shaped HOLC and its maps. Hoyt, he noted, used a 1933 academic paper that “graded various nationalities in order of their real estate desirability.” At the top of the scale were whites of “English, Germans, Scots, Irish, Scandinavian” descent. At the bottom of the list, below “South Italians” and “Russian Jews of the lower class” were “Negroes” and “Mexicans.” At the time, deeds could still carry explicit “covenants” that prohibited buyers of certain races or ethnicities, and HOLC maps draw from those as well. In fact, the program even strengthened them in its quest to “stabilize” neighborhoods.

Eugenic beliefs about “desirable” and “undesirable” populations, often ground in shaky pseudoscientific theories combined with outright bigotry, held a surprising influence over political decision-makers at all levels at the time, and for over a decade after. In their cruelest form, they fueled programs like the sterilizations North Carolina is still grappling with. HOLC and the redlined maps weren’t quite as blatant, but they had their own devastating impact.

HOLC forms for various neighborhoods, included as part of the mapping project, had a line to specifically note percentage of “negro” population or of “foreign nationals” living in an area. It even had a spot to note “infiltration,” or changing racial and ethnic make-up in a neighborhood, because Hoyt’s criteria declared that integrated neighborhoods were unstable.

The results are stark. While a close-knit neighborhood with a well-known local agricultural fair, churches, schools and businesses, Burton Street was redlined in the 1937 reports. Despite the presence of a large commercial district, an acclaimed school, civic institutions and “all city conveniences,” even by the HOLC evaluation’s own admission, a massive swath around downtown, including East End, Southside and Hill Street, suffered the same fate.

The reports noted that Burton Street was “100% Negro” and Southside/East End/Hill Street was “75% Negro.” In fact, all the city’s neighborhoods with a majority African-American population were bounded by the federal government behind red borders, tagged as blighted, unworthy of aid. Long after HOLC was over, this designation would have far-reaching consequences.

A 1964 booklet from the Housing Authority of the City of Asheville, touting increased tax values from urban renewal. From UNCA, D. H. Ramsey Library Special Collections

‘Urban removal’

The overlap of the HOLC and urban renewal maps also shine light on one contradiction that’s long stuck out about Asheville’s own urban renewal: governments considered whole neighborhoods “blighted” and fit for demolition while residents described places that were home to locally-owned businesses and working class people proud of their communities.

“You had thousands of people that had lived there their whole lives,” Ndiaye remembers. “People stuck together, they helped watch out for the children. If you owned a paint company or were a mechanic, you mentored and you trained and taught the young.”

Urban renewal was complicated, she notes, and some — including her family – initially viewed it as a boon.

“We were going from a two-bedroom, rat-infested home to a new four-bedroom apartment, so that was a good thing.”

But while there was certainly plenty of poverty and “some of the areas were blighted,” Ndiaye recalls, “The whole neighborhood was not blighted; there were some good, solid homes.” They were demolished too.

“That was disturbing. You had a lot of elderly women who had worked all their lives along with their spouses. Many of them were widows, and they’d paid for their homes. They owned them,” she says. “Now you go into their neighborhood, you take their homes, you promise them they can come back.”

“But many didn’t come back,” she says. “All this was in the name of economic development, that it was for the good of the city. But when it came to the people involved, well, many call it ‘urban removal.’”

The urban renewal grants were based on the “entirety of the neighborhood being blighted,” Ndiaye notes, and they were considered blighted often because they were redlined. Decades separated HOLC and urban renewal, but by that point, the maps shaped by archaic eugenics theories had a surprisingly long life.

“What you see in Asheville is stunning: the urban renewal projects coincide precisely with the redlined areas from the 1930s,” Marciano says. “There’s absolutely no room for speculation here: it’s one policy seeping into another. Those neighborhoods that were singled out under redlining — and labelled as areas that should not be reinvested in — come out in the 1960s and ’70s policies selected as candidates for putting highways through them or for eminent domain.”

Urban renewal maps, with roads in bold, overlaid with the 1937 redlining districts for the areas around downtown, including Southside, Hill Street and East End neighborhoods. The red pointers are housing projects, most built during the ’50s and ’70s. Full interactive map from the Southern Redlining Collection here.

Interestingly, he notes that one redlined section in Asheville wasn’t African-American: a swath near Amboy Road, described in the 1937 reports as inhabited by “cheap white laborers — railroad men.” It was not targeted for urban renewal in the decades that followed.

“This is sort of an interesting case of redlined areas: a white redlined area and a black redlined area,” he says. “On the surface, at least, you can see how they were treated differently. It’s definitely food for thought.”

While the HOLC maps were supposed to be secret, historians like Nathan Connolly of Johns Hopkins, interviewed along with Marciano on The State of Things, note that local political and business elites ended up with access and could then use them to shape their own criteria for lending or redevelopment. The effects of HOLC lingered long after the corporation was dissolved in 1951, and it continued, fueled by cultural prejudice, even after a 1948 Supreme Court ruling found enforcement of racial covenants unconstitutional and federal legislation in the late 1960s made redlining based on race technically illegal.

“My theory is that they didn’t need to be used beyond the first few decades: everyone knew what these things were and they had a life of their own,” Marciano says.

As if that wasn’t enough, enforcement remained elusive even after the new court rulings and laws. As a This American Life report late last year detailed, attempts to turn the ban on racial housing discrimination into reality were vigorously fought through multiple federal administrations and still remain an issue today.

“Several decades later this stuff was still being litigated,” he says. “This showed the persistence of these policies, even when they’re outlawed or rendered unenforceable. Once these tools are in place, it almost becomes self-fulfilling; you don’t even need to enforce them.”

A Pulitzer Prize-winning series in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution in the late 1980s showed, for example, that the legacy of redlining still excluded many middle and even upper-income African-American families from obtaining fair housing loans.

Ndiaye, after observing the impact of urban renewal firsthand and researching it extensively, has a map of all the properties affected in the Southside neighborhood, and which ones were redlined, telling the story of homes and businesses demolished. Rolling it out on a table, she points to the house her family rented, and those of neighbors and friends. She and Marciano went through extensive local property records and UNCA’s archives to help assemble the map.

“When you say 1,200, it’s one thing, then you look at it,” she says. “All these homes were taken. When you start multiplying two, three, four, even nine people inside each of these homes, that’s the impact.”

“You can see, up to the red line, what wasn’t touched.”

Many residents in the area rented, as the effects of redlining combined with lower wages made the prospect of homeownership difficult. Many that did own their homes saw them taken. Often, the compensation offered for a home in the “blighted” area wasn’t enough to purchase another. Many had scrupulously saved money to buy their homes, she notes, but by the time urban renewal came they were retirees with more limited incomes.

“When urban renewal came through, it divided up the community; some still call it ‘divide and conquer’,” she says. “Now all the wisdom, all the elderly women, are up in the high rises on South French Broad. It broke down a connected community.”

And if they wanted to get a loan so they could buy another home and stay in the area, Ndiaye notes, many were out of luck.

“Once they gave the address or the zipcode, you knew not to approve the loan,” she says. “Because the neighborhood was redlined.”

The fallout lingers

Marciano believes increased insight into the history and injustices a city has endured is one of the reasons tools like these digital maps can be so powerful.

“That’s the promise of a lot of these digital projects: being able to ask more global questions, interact with the materials and really question some of the prevailing assumptions,” he says. “Good or bad, with what’s happening now it really helps to put it in context, where you can see the cumulative impact of these policies. If nothing else, it’s a way to make sure we don’t repeat the past.”

The city of Asheville recently completed a study of gentrification and its alternatives “East of the Riverway,” a broad swath that includes much of an area redlined under HOLC’s 1937 maps and hit by urban renewal, such as Southside. There, incomes still lag far behind the rest of the city, with 57.3 percent of the population living below $25,000, as compared to 29.5 percent in Asheville as a whole. The study mentions the “rich history, often marked with pain” of the area.

The memory remains fresh, the study notes, and with rising home prices pushing out many, especially the African-American population, “there is concern another wave of displacement is coming.”

Ndiaye hopes that the new efforts, in this case intended to tackle gentrification, will take the past into account and finally learn from it.

“If we sit down and have the conversation, and I say ‘we’ as the community and the city, you can look back and learn from what you did and see how it truly impacted the people,” she says. “Maybe that can show you and teach you some things that you don’t want to do again.”

But even the very terms still used by today’s urban planners still bear the shadow of urban renewal, Ndiaye notes.

“East of the Riverway was the term they used on the urban renewal applications; we’d always called it Southside.”

Meanwhile, in the housing projects that ended up home to many of those pushed out by urban renewal, a sweeping overhaul intended to put housing on firmer financial footing has some residents skeptical that it’s a backdoor way to privatize and push more people out. In the words of Hillcrest resident Olufemi Lewis, a critic of the change, “this feels a lot like urban renewal.” The measure comes up for a final vote tomorrow evening.

As for Eagle Market Street, the area saw a bevy of different development proposals flounder for decades before the newest affordable housing development finally broke ground.

Burton Street has seen a revival in recent years, but still faces an uncertain future, with the proposed Interstate 26 connector threatening to take homes from the area and further impact the community. Earlier this year, neighborhood leaders said they still felt like their voices are ignored by local and state leaders planning to again expand the interstate.

The legacy of urban renewal in Asheville and the redlining that shaped it, Ndiaye says, “remains unresolved.”

“We’ve been having a little conversation here and there about it,” she says. “But it’s 50 years later, and we’re still seeing the impact now.”

—

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by its readers. If you like our work, support us directly on Patreon. Questions? Comments? Email us.