The Flatiron hotel proposal comes back before Council tonight. Behind the vindictive rent hikes, sleazy connections and special exceptions made for the hotel project the public hates

Above: The Flatiron building, home to 80 local business and organizational spaces. A proposal before Asheville City Council would turn 71 of them into hotel rooms

Tonight (5 p.m. on the second floor of City Hall) Asheville City Council will once again decide on whether to turn the Flatiron building into a hotel.

It seems like just yesterday locals rallied to fight against this very thing. On May 14, following months of public outcry and nearly two hours of Ashevillians four Council members made it clear they were against the project. In the weeks leading up to that, the Blade published a primer on the importance of the Flatiron fight and its role in the larger political battles over the explosion of hotels in our town.

The project seemed to crystalize nearly everything awful about this particular wave of gentrification. It doesn’t just place another hotel across from two hotels, it kicks out nearly 80 local businesses and organizations, For good measure it even violates the city’s own rules on parking (it would take spaces away from already crowded public decks) and accessibility (it would only have a single loading zone, and would take up a chunk of public sidewalk to do it). Beyond that, if Council passes it, they will send the signal to numerous waiting hoteliers that they’ll basically pass anything, and the floodgates would open on even more hotels.

That galvanized an overwhelming level of opposition to the project, and it seemed to be enough to push a slim majority of Council against the project. But just over a month after its initial defeat, the Flatiron hotel proposal is back, with no public input and hardly any changes.

The time since has proved illuminating, with Flatiron tenants facing massive rent increases and the sordid history of one of the building’s main owners (including indictments for fraud, a lawsuit for unsafe buildings and a conviction for illegal prescription drug sales and money laundering) coming to light. Meanwhile, some in our local government have seemingly doubled over backwards to bring this back to the dais with lightning speed. So here, readers, is an updated, even more direct primer on what’s going on.

What the hell just happened?

Yes, indeed, four Council members (Julie Mayfield, Keith Young, Sheneika Smith and Brian Haynes) did announce their opposition to the Flatiron hotel project on May 14. If they’d followed through with an up-or-down vote on the project, that would have buried it for a year. Instead, they let the attorney representing hotelier Phillip Woollcott withdraw the proposal. This isn’t unheard of (which also speaks to the deference Council gives to property owners with money) but the speed with which the hotel deal ended up back before Council is.

Typically, controversial development projects that get bounced from Council take months to end up back before them, usually with some (often insufficient) concessions to the concerns of the opposition. Not this time. The Blade has spoken with several prominent Flatiron hotel opponents and none were ever contacted or notified by the developer about any attempt to assuage their concerns. No public input session was ever held.

But while Mayor Esther Manheimer didn’t announce a firm position on the hotel project on May 14, she did seem deeply sympathetic to Woollcott and building owner Russell Thomas, praising rich developers as the people who built downtown (they conjured all those buildings out of thin air, perhaps) and saying she understood why they’d see it as a “slap in the face” that they couldn’t turn as much property as they wanted into hotels to make as much cash as possible.

Instead of 80 hotel rooms, the project now proposes 71, retaining nine spaces for businesses or organizations. If that’s enough to sway a Council vote, Woollcott and Thomas are getting them for cheap.

Why the project’s being rushed back so quickly remains, at least publicly, a mystery. Perhaps some part of the development deal or financing expires in July or August. If that’s so, it’s worth wondering why a hotelier’s rickety schemes should dictate a government process. Also highly unusual is that Manheimer, who won’t be present at tonight’s meeting, has received a special exception to attend and vote by phone. I’ve covered Council for 13 years, and that’s nearly unheard of (Manheimer’s certainly felt no need to request it for a multitude of other pressing matters).

That’s a lot of effort by local government officials to seemingly smooth the process for those involved in a deal the public hates. It’s worth taking another look at who they’re exerting all that effort for.

Who’s profiting from this?

While the exact terms of this deal aren’t public, the last asking price for the Flatiron was a cool $16 million. The Flatiron is owned by an LLC, Midtown Development. There are two members of that LLC. One is Russell Thomas, who’s been most prominent. But the other owner is a trust for Marshall Kanner, who’s received far less attention.

Thomas’ actions have included blatant classism, failure to maintain an aging building for over three decades and, most recently, a brutal rent hike on tenants after his hotel scheme initially failed to go through. Kanner’s record includes indictment for alleged land fraud, a lawsuit for collapsing condominiums and federal prison time for money laundering and illegal distribution of prescription drugs.

That’s who’s going to profit off this deal.

Let’s take them one at a time. Thomas has been the public face, claiming that he’s just involved in a potentially lucrative hotel deal purely out of altruistic concern for the building’s preservation. Apparently, the building requires $10 million in renovations and repairs, supposedly making a luxury hotel the only option.

It’s worth questioning what he was doing as the owner while the building apparently was practically falling down. It’s also worth questioning that $10 million dollar estimate. If it includes the cost of the fancy “speakeasy” and bar the hotel plans to open, or the costs of installing bathrooms and showers in every unit when they’re converted, then the actual costs of renovating the space to continue in its current would be far lower than the estimates Thomas and Woollcott are touting. It’s profitable for them to make a hotel seem inevitable.

Thomas has also indulged in blatant classism. At the planning hearing on the Flatiron proposal, he dismissed the tenants who’ve made his living possible as people “who don’t have a lot in the game, just looking to get by.”

While claiming care for the tenants and the future of the building, Thomas’ actions after the hotel proposal was initially defeated tell a different tale, of a gentry landlord turned vindictive when denied his way. The day after Council refused to pass his hotel project, many tenants within the Flatiron saw rent hikes of 50 percent or more. One longtime tenant, for example, saw her rent go from $325 a month to $500.

Kanner was, as of last week, still listed as a member of Midtown Development in official state documents. Kanner’s history, recently researched by by Downtown Commission member and hotel opponent Andrew Fletcher, is even more sordid.

He first entered the public eye in 1985, when he was named in a federal indictment alongside Madison County political boss Zeno Ponder. That indictment alleged mail fraud in relation to a land deal that Ponder had special knowledge of due to his role on the state board of transportation. Kanner was already one of the partners owning the Flatiron building. The indictment didn’t stop Asheville City Council, then led by Mayor Louis Bissette, from voting $800,000 in bond money for the Flatiron’s development as a retail and office space in 1986 (the money was never issued and the Flatiron’s owners opted to go for private funds instead).

While Ponder and Kanner were hit with further charges, they were eventually dismissed in 1986. In 1990, Kanner was sued by a condo owner claiming that the Windswept condominiums that Kanner built had started to collapse in 1989. That lawsuit, which also named the city (for allegedly failing to properly inspect the buildings) was dropped in 1991, after the N.C. Supreme Court ruled the city couldn’t be held liable. An attorney for the plaintiff claimed the lawsuit’s end was due to a lack of resources to pursue the case further.

In 2007 Kanner was charged with 31 counts related to running an illegal business selling prescription drugs online. He later plead guilty to illegal drug distribution and money laundering and served 32 months in federal prison before being released in 2010. The federal government seized over $3 million and possessions including cars and a boat.

When Manheimer praised developers as the people who built downtown, I wonder if this what she had in mind.

There’s more. McGuire, Wood and Bissette (yes, that Bissette is former Mayor Louis Bissette, during whose tenure Council signed off on $800,000 to the firm partly owned by someone indicted for shady land deals) dealt with Kanner until at least 2006. Two dissolved development groups Kanner owned listed the law firm’s offices. The firm was also hired by the city of Asheville to provide an interim city attorney and legal services when the Flatiron proposal began to wend its way through the city’s development process last year.

According to subsequent Citizen-Times coverage of the documents raised by Fletcher, the firm has claimed that they weren’t involved with the hotel proceedings. However, it might not take that much to throw a giant wrench in the approval process. Manheimer, who works as an attorney with the powerful Van Winkle firm, has repeatedly had to recuse herself from Council proceedings because a developer has hired another attorney at her firm for unrelated matters. If McGuire, Wood and Bissette still had any current connection to Kanner when they started working for the city in 2018, that raises serious problems about the entire process, possibly enough to scrap it entirely.

What is indisputable is that Council is now aware of Kanner’s record and connection to the Flatiron. Fletcher emailed them a link to the documents on June 22. Council member Brian Haynes replied the next day, noting he would push to delay the matter to consider the many concerns these documents raise. If the rest of Council will insist on ramming the Flatiron deal through anyway remains to be seen.

Who’s getting hurt?

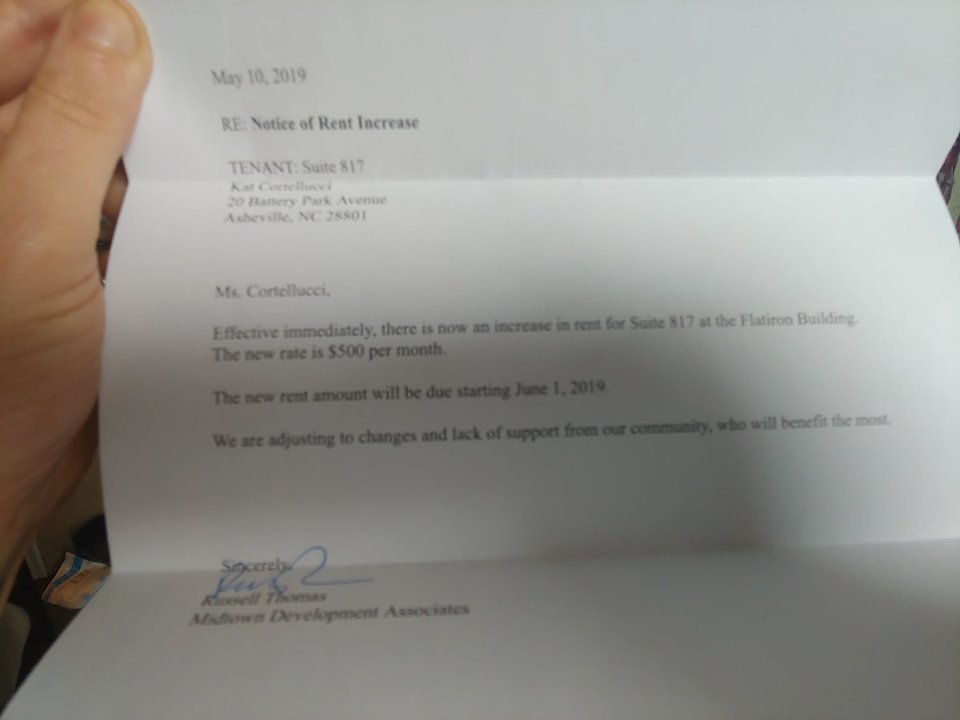

A rent increase notice received by Flatiron tenant Kat Cortellucci, a local massage therapist, on May 15, the day after Council declined to approve the hotel proposal. Her rent increased from $325 to $500 a month due to ‘lack of support from the community’

Central to the Flatiron fight has been the number of tenants the new hotel would kick out. Because the building is home to some of the last non-gentry business and organizational space in downtown, many of the tenants aren’t exactly wealthy, leaving them with limited options.

But so far the voices of Flatiron tenants have largely been missing, other than a few trotted out by Thomas to voice approval of the hotel. This isn’t entirely surprising. Landlords have a lot of power in North Carolina and for those already living precariously, it’s a daunting prospect to fight one in public.

But now one has broken that silence. Kat Cortellucci, a local massage therapist, had a space in the Flatiron for 13 years. Most of the time, she tells the Blade, her experience was fairly positive.

But then the push to turn the building into a hotel and kick out the tenants, her included, ramped up.

Were they opposed to their own removal? “Of course we were,” Cortellucci notes. She asserts that, contra Thomas and some other hotel supporters, most of the building’s tenants, working-class locals “who didn’t own anything,” were against the hotel.

The day after Council declined to move the Flatiron hotel forward, Cortellucci received a letter from Thomas. It informed here that two weeks later her rent would skyrocket from $325 a month to $500, because, Thomas claimed in a vindictive note, “we are adjusting to changes and lack of support from our community, who will benefit the most.”

Cortellucci believes Thomas upped the rent specifically on longtime tenants who had somewhat lower rates; those less likely to have wealth or other funds to fall back on.

“He basically wants to retire with a lot of $$. That’s it in a nutshell,” she writes to the Blade. “Decisions currently seemed to be based off that and [Woollcott] wants a massive money-maker instead of a project. Shortsightedness and greed are the bases of this entire operation.”

Scrambling, she was able to find another space, but wonders if other tenants will be so lucky.

“I am just over being caught in the crossfire of this shit storm. I gave up the only stable part of my life in Asheville because of this. I am done.”

What’s going to happen?

Honestly, it’s anyone’s guess. The Flatiron fight was already a flashpoint for the battles over gentrification. If the mass evictions, city officials bending over backwards and a hotel across from other hotels didn’t already personify much of what’s wrong with Asheville, the brutal rent hikes, rushed process and the hidden co-owner with a history of fraud indictments and money laundering sure as hell do.

In May it looked like Council had — belatedly and after a lot of community pressure — finally started to get some iota of determination to resist. That the Flatiron might prove a step too far, that community outrage had finally been heard.

But the community was outraged over the recent city budget as well and on June 11 Council passed that unanimously, with even Council members who’d previously voice objections silently dropping them. Since then, I’ve heard everyone from outraged locals to longtime advocates wonder if there’s any limit to Council’s capacity to ignore the public in favor of wealthy “stakeholders.”

If Council passes the Flatiron hotel tonight, despite the slew of ever-increasing problems, they’re telling you where they stand.

Politicians are not your saviors and they are not your friends. Public anger is the reason the Flatiron didn’t pass in May, and if it doesn’t pass tonight, public anger will be why.

That part, reader, is up to you.

—

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by our readers. If you like what we do, donate directly to us on Patreon or make a one-time gift to support our work. Questions? Comments? Email us.