Last April’s police raid on the Aston Park camp set the model for future crackdowns. Documents reveal city officials rejoicing over arrests and seeking to please gentry groups

Above: Asheville police gather for the April raid on the Aston Park camp. Photo by Veronica Coit.

The Blade is currently raising funds to support our journalists arrested for covering the Dec. 25 police crackdown. Make a one-time donation here. Or subscribe here. Any amount helps.

On April 16, 2021 nearly the entire on-duty police marched down South French Broad Avenue to Aston Park. There they attacked a houseless camp and locals who’d shown up to support it, dragging four people away in handcuffs. Cops would arrest three (including one on a blatantly false assault charge) and take another to the hospital.

To any human being with anything resembling a soul this would be ugly, tragic, even enraging. But not for city manager Debra Campbell.

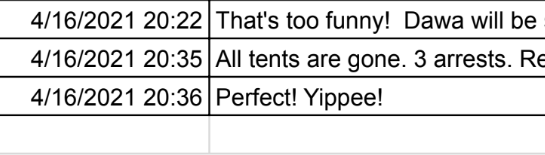

“Perfect! Yippee!” Campbell, who’d ordered the crackdown, exclaimed in a text message to police chief David Zack that evening, after he informed her that “all tents are gone. 3 arrests.”

Meanwhile Mayor Esther Manheimer was passing on the personal thanks of the head of a gentrifying “neighborhood association” to Zack, Campbell and then-assistant city manager Cathy Ball.

The raid last spring turned out to be a harbinger of things to come: huge police presence, trumped-up charges to punish protest and the use of “outside agitators”-style propaganda to try to discredit solidarity between housed and unhoused locals. We’ve seen such tactics escalate since.

Part of an April 16 text exchange between City manager Debra Campbell and APD chief David Zack. Campbell exclaims “Perfect! Yippee!” in response to arrests during the Aston Park eviction

In the aftermath of the April attacks, the Blade and the open records group Sunshine Request sought to obtain records of what was going on behind the scenes, among those who ordered the police assault on the camp. It took over nine months, which is apparently city hall’s idea of turning documents over, in the words of state records law “as promptly as possible.”

The documents were released in two waves on Jan. 27 and Feb. 4. They remain incomplete, with several parts redacted without explanation and other key information missing.

But from what is revealed it’s easy to see why they drug their feet. The records — emails, text messages and call logs — show city officials excited about arrests and eager to please conservative gentry transplants even while a wave of locals called on them to stop the sweeps.

Recently there’s been a common observation from members of the public that Asheville city government is waging a war on the houseless. This is accurate. In war it’s easy to focus on the crimes of the foot soldiers and lose sight of who’s ordering them. The officials and property owners in the accounts that follow are as responsible for violence against the unhoused as the cop swinging a club.

Coordinating the crackdown

Police gathering in Aston Park before the April 16 raid. Around 40 would deploy to evict on houseless camp. Special to the Blade

By the afternoon of April 16 it was already crystal clear that the Aston Park raid wasn’t some cops deciding to just attack the camp. Instead the orders came from the very top. Police on the scene said that Campbell had personally directed their actions. This was later backed up by Council member Kim Roney, who said that the matter had been approvingly discussed between the city manager, mayor and two council members at one of their secretive weekly “check-in” sessions.

The newly available records reveal far more. On April 9 APD Capt. Mike Lamb contacted Campbell and top city officials, writing that “per our earlier conversations” seven-day eviction notices had already been given to the campers. Campbell noted that then-Assistant city manager Cathy Ball would return to the office in a few days “and has scheduled a meeting with city staff and key partners to continue coordinating this work.”

Campbell also was in close communication with Zack days ahead of the raid. On April 13 the police chief texted her about “some chatter of a protest tomorrow night.”

“Please tell the officers to keep safe and keep me posted,” she replied.

Apparently the idea of houseless people sleeping in a park was enough to literally keep Campbell up at night, because just after 10 p.m. on April 15 she texted Zack “Hey chief hate to bother you this late at night but I was wondering if you had heard if there is any activity happening in the park(s)?”

The next morning Zack replied that he’d update her shortly due to “some issues we’d anticipated.”

APD Capt. Mike Lamb threatening campers at Aston Park with arrest on the morning of April 16. Photo by Veronica Coit

That afternoon Campbell coordinated a 3 p.m. meeting. Things escalated from there, as then-Parks and Rec director Roderick Simmons went to the camp, repeatedly yelled at campers, and started trying to take tents down personally even as the people there informed him that others were coming back for those tents. He then called the cops and falsely claimed “agitators” were attacking him. His lies would later be used in city hall p.r. to claim “obstruction.”

“He is at Aston Park now,” Ball texted Campbell that afternoon. “I asked him to contact a biohazard cleaning company to clean up the park.”

Ball, who would later leave city hall for a job in Johnson City after calls for her resignation due to repeated anti-houseless remarks, did not specify why biohazard removal might be needed. In observing the camp at different times of day, three Blade journalists witnessed nothing beyond campers’ belongings, food supplies and the amount of trash that naturally comes with people existing.

“Arrests will be needed at Aston Park,” Zack messaged Campbell early that evening. “Captain [Jackie] Stepp is getting no compliance.”

After a brief back and forth about an untrue rumor that an ICE van was on site (“that’s too funny!” Campbell texted the police chief), early that evening Zack told Campbell “All tents are gone. 3 arrests.”

“Perfect! Yippee!” she replied.

The exchange also shows them coordinating on the ensuing propaganda (the Dawa mentioned in the texts above is city pr head Dawa Hitch), which would try to paint the only people left at the camp as “protesters” while the actual houseless people were all supposedly docile and cooperative, happy to take city hall’s supposed offer of a night in a hotel.

The documents show Council member Sage Turner, who would “applaud” future APD camp crackdowns and supports a de facto ban on food and supply distribution, liked the press release when it was shared with a council group chat.

The city’s propaganda was, of course, untrue. On the contrary, Blade journalist Veronica Coit witnessed the decision to stay in the camp made primarily by houseless people there, backed up by local supporters who were against them losing the only shelter they had.

Many campers, fearing police violence, did leave, and not for hotel rooms. Plenty of houseless people who left the camp didn’t want to do so: they were under threat of arrest. Indeed a houseless person was detained by police that day along with the protesters, but transported to the hospital rather than being booked at the jail. Buncombe detention center is the deadliest jail in the state.

Council’s been incredibly secretive about how decisions about camp evictions are made, but the messages reveal a little more about the divides among the city’s elected officials.

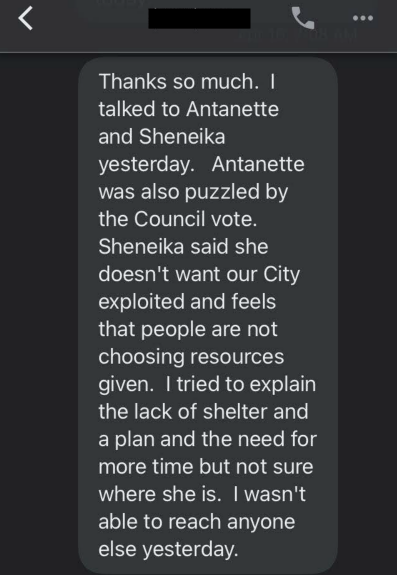

On April 14 a member of the public whose identity is redacted in the records — seemingly involved in houseless services — texted Council member Kim Roney that they’d heard about the looming raid “in a meeting today when I was pushing to pause the evictions so that we can create a genuine safety plan and housing plans for individuals.”

A person, whose identity was redacted in the city records release, talks to Council member Kim Roney about the internal politics behind the secret decision on evicting the Aston Park camp

“I was told that City Council made the decision last week to evict campers,” the person wrote. “Can you tell me more about how all that happened?”

The decision, such as it was, happened in a secret “check-in” session of city council. These weekly meetings are supposed to be informal chances for rotating three-person groups of council members to discuss policy priorities. But records show that they’ve become full-fledged secret meetings, complete with policy decisions and confidential legal advice. While documents presented at the meetings are public, they have no minutes or records of who said what. They violate open meetings and records laws on multiple fronts, and are part of council becoming more right-wing and far less transparent.

On the morning of April 16, the same person messaged Roney again, noting they’d talked to Council member Antanette Mosley and Vice mayor Sheneika Smith. Mosley “was also puzzled by the Council vote” and apparently wasn’t at the check-in session. But it’s implied Smith was, and “said she doesn’t want our city exploited and feels that people are not choosing resources given.”

The person messaging Roney said they brought up to Smith that the city’s houseless population is disproportionately Black, but that the person was “not sure where [Smith] is” on camp sweeps.

“Our city has been exploited by the tourism industry and will continue to be exploited by people with wealth staking claims for multiple homes, and some are doing it on purpose in advance of climate catastrophe,” Roney wrote during the conversation. “We are the health and human services hub for WNC with a good V.A. Where are people expected to go?”

It is the only time in any of the exchanges obtained by the Blade and Sunshine Request that any official raises any concerns about the evictions. Roney was, however, pretty mild in her criticism.

“I’m trying to acknowledge that each of us is doing what is right in our own way,” she says about her colleagues ordering the eviction and arrest of human beings. “But this journey has been very hard.”

Pleasing the gentry

The documents also answer a question we’ve gotten at the Blade. It’s clear that camp crackdowns are not popular in left-leaning Asheville. Indeed, the public backlash to them has only grown, with the broad coalitions against them including not just leftists but longtime houseless services organizations and religious groups.

While city government’s always been hostile towards the houseless they’ve historically tried to be more low-key. Large, brutal public crackdowns are fairly new, part of a sharply conservative shift in council over the past year.

So, who are they trying to please? The messages reveal a lot about this, showing a small group of gentrifiers communicating extensively with police, city administrators and the mayor in pressing for crackdowns. It also shows officials eager to please.

“Chief, Debra and Cathy – thank you all and your teams for the work today and tonight, I know it was stressful and difficult,” Manheimer wrote the city’s top officials in the hours after the raid. “I spoke with the head of the SFB neighborhood associations and they appreciate your efforts.”

SFB is South French Broad. Despite the name, the “neighborhood association” there is made up primarily of well-off white transplants in a working-class Black neighborhood.

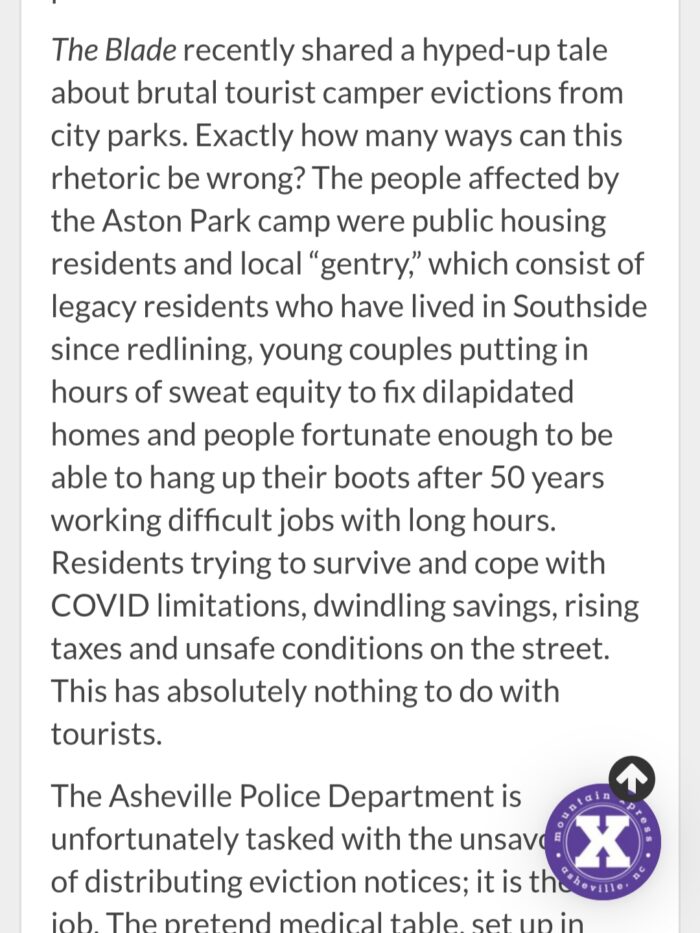

The head of this group is Helen Hyatt. Just over a month after the raid, she penned a screed to the Mountain Xpress, attacking the Blade specifically and praising the evictions.

A pro-camp eviction screed penned by “neighborhood association” head Helen Hyatt, who city officials sought to please with the April raid

According to multiple sources Hyatt, who bought a house in the neighborhood less than a decade ago, has been particularly vocal in pushing for police crackdowns on sex workers in the area. This is backed up by a 2020 Asheville Citizen-Times piece noting her work with a particularly right-wing APD liaison officer “on curbing drug dealing, open prostitution and other issues.”

On the day of the raid Hyatt took screenshots of tweets by Blade reporters Veronica Coit and myself supporting those pressing city officials for an end to the sweeps. She sent them in a personal email to the mayor.

“They are setting up Asheville to fail, especially APD,” Hyatt wrote to Manheimer.

The Blade co-op is, to a person, strongly anti-eviction. I’m sure this will come as a shock to our readers.

In her May column Hyatt, a white gentrifier, claimed to be speaking for a mostly Black community. By contrast Blade reporters observed some Southside residents — including some in Aston Park Towers supportive of the later December camp on multiple occasions.

The April emails show that instead of a wave of broad neighborhood support for Hyatt’s position, the only South French Broad residents writing in to back the evictions were two other well-off white transplants.

Asheville Mayor Esther Manheimer, who sought to please local gentry with the Aston Park raid. File photo by Max Cooper

“Thank you for sticking to your conviction regarding the dismantling of the Aston Park encampment,” Reuben DeJernette wrote to council. “I was able to walk through the park unencumbered by the foul language from our visitors this morning. It was refreshing.”

He recommended the city prepare for more camp evictions in the future due to the looming expiration of the eviction moratorium kicking people out on the street.

DeJernette, who bought a house in the area for $355,000 four years ago, was quoted in a 2020 Christian Science Monitor article with some quasi-racist comments about the reparations issue.

“There is no escaping that we have been doing the Black community wrong, but every time I go over it in my head I don’t know what can be done to fix it.” He proceeded to spend significant time in the coming year pressing city officials for more police crackdowns.

McKenzie Brazil, a doctor employed by Hendersonville’s Pardee health system, wrote to city hall claiming that “allowing [campers] to continue to stay only encourages the spread of infectious disease,” a position contradicted by the entire field of epidemiology and public health.

Brazil purchased a house on South French Broad for $380,000 in 2019. The property records show a tale of gentrification in miniature, with property doubling in value from a $150,000 sale in 2013 as repeated waves of transplants flipped it. Brazil is the latest. In her email to council she wrote without a trace of irony that she was one of the “actual residents of these communities.”

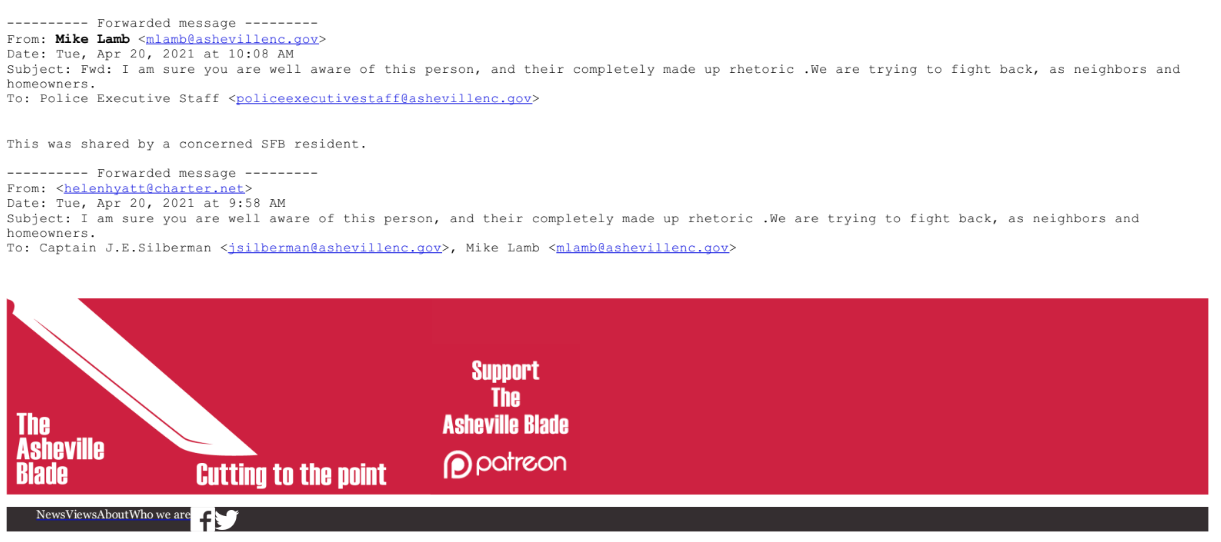

Ominously, something else comes up in the documents too. A few days after the raid Hyatt personally notifies Lamb about the Blade‘s reporting on the camp evictions, pasting in the entire article.

Helen Hyatt, the head of a gentrifying “neighborhood association,” targets the Blade’s coverage in an email to APD Capt. Mike Lamb, who passed it on to top police commanders

“I’m sure you’re well aware of this person,” Hyatt writes in the subject line. “We are trying to fight back, as neighbors and homeowners.”

Lamb passes along to the APD’s top commanders, with the note that “this was shared by a concerned SFB resident.”

Zack then forwards Hyatt’s email about the Blade article directly to Campbell.

The next time Blade reporters would cover a police raid on a houseless camp, APD officers would target and arrest them first.

‘Telling them to disappear’

The documents paint a bleakly telling picture. Campbell’s astoundingly callous reaction to the arrests puts the lie to the constant claims that her administration gives a damn about equity. These are the actual views of the most powerful official in city hall when she’s out of the public eye, and they show a giddiness over punishing the poor.

Hyatt’s belief that the gentry being well-off and oh-so virtuous (“sweat equity”) gives them the right to call in an armed paramilitary any time they see someone they don’t like is equally revealing. So are the classism and entitlement openly expressed by the other transplants pushing for evictions. These are the beliefs of those city hall is bending over backwards to please.

After the April Aston Park raid city government backed off — a bit — offering spaces at the former Ramada Inn to houseless people in other camps instead of just evicting them outright. They didn’t do this because they wanted to, but because public outrage was growing while police numbers were dwindling. Repeatedly deploying the entire on-duty APD to face direct action was not something they could sustain for long.

But last Fall and Winter officials promptly reversed course, suddenly scrapping plans to turn the Ramada into a low-barrier shelter after pressure from far-right business owners. Police retaliation also increased. During the infamous Christmas night raid police targeted journalists first before dragging people out of tents. They followed up with a wave of arrests in the weeks after, hauling people away from work in handcuffs and from their homes at night. The APD hit them with clearly false “felony littering” charges for having art supplies in a park.

Notably, while hanging on the every word of rich transplants, Asheville police would portray working class locals targeted with anti-protesting charges as suspicious outsiders. Their most recent pr barrage listed those arrested’s homes as the last place they lived before Asheville, even if they’ve lived here for years.

But during the Aston Park raid something else happened. Members of the public across the city were sending in a barrage of messages against the evictions. On this front too the documents are revealing.

They’re a reminder that while an increasingly brutal approach to the houseless might be city hall dogma, it’s a policy hated by many locals on the ground.

The earliest rebuke was on April 13, when a resident emailed council that “it is absolutely unacceptable to dismantle the homeless encampments” before the city had a clear plan to provide shelter for everyone there.

Similar messages only increased in the days after. Of the 12 people who emailed city officials about the evictions, nine — everyone except the gentry transplants mentioned above — were strongly against them.

“I’m writing to urge you and the rest of city government to please comply with CDC guidelines and pause all evictions in Asheville, including people living in homeless encampments,” Zeb Camp wrote to Campbell on April 16.

“I believed your statements after the Lexington Bridge travesty,” Sandra Houts said in an email to the city manager. “No longer do, nor do I expect to believe much of anything coming out of the manager’s office or council chambers in the near future.”

“I am ashamed of how our city is treating our homeless community here,” Angelica Danielsen said. “Provide housing and stop these evictions. It is inhumane to deny shelter. Especially with our shelters full during a dangerous pandemic.”

Perhaps most telling is a message from the Hawthorn Community Herb Collective to the city manager.

“You tell them to leave Aston Park — but where do you want them to go? You’re basically telling them to disappear.”

—

Blade editor David Forbes has been a journalist in Asheville for over 15 years. She writes about history, life and, of course, fighting city hall. They live in downtown, where they drink too much tea and scheme for anarchy.

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by our readers. If you like what we do, donate directly to us on Patreon or make a one-time gift to support our work. Questions? Comments? Email us.