With the city of Asheville considering more incentives for “affordable” and “workforce” housing, it’s worth looking at what that means.

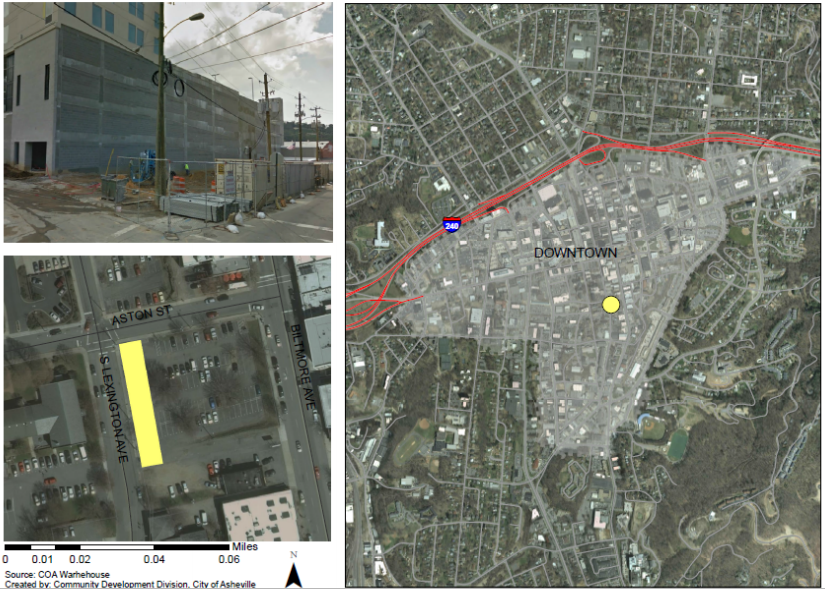

Above: An image from the city of Asheville’s documents of the proposed site of 32 “workforce” housing units on the back of the Aloft Hotel in downtown.

On Tuesday, Sept. 23, Asheville City Council will vote on whether or not to give incentives — in this case that the city spend $250,000 to bury power lines — to developer Public Interest Projects so it keeps 32 units it’s planning to build downtown at “workforce” rental rates. City staff have endorsed the proposal.

Last month, Asheville City Council voted $765,000 in tax breaks for the RAD Lofts project, despite concerns about a lack of affordability. Part of developer Harry Pilos’ call for incentives — in addition to touting the economic impact — was the number of workforce units the project would produce in the area.

Among the criteria for city incentives are the number of “affordable” and “workforce” units a project will build. Asheville’s in the middle of a housing crunch, even making some national lists for its lack of affordability, and successive Councils have made incentivizing affordable — and more recently, workforce — housing a priority with either direct loans or tax breaks.

So what do city officials mean when they say that housing is “affordable” or, for that matter, “workforce?”

The city bases these rent caps off of the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development’s criteria for an area’s annual median income. For affordable units, the city divides 80 percent of HUD’s median income by 12, then tags 30 percent of that as an affordable rental rate. For workforce units, it uses 120 percent of the median income when calculating the rent limit.

“That amount is the accepted standard for what a household should reasonably pay for rent and utilities on a monthly basis,” Jeff Staudinger, the city’s assistant director for community and economic development, writes in an email explaining the criteria.

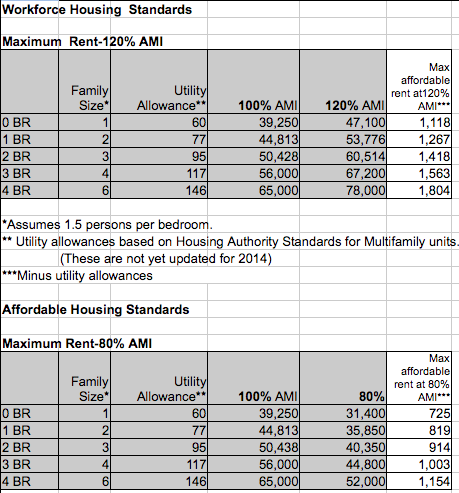

This — with a utility allowance figured in — totals out to the following as the affordable and workforce rates for Asheville:

A screenshot from the spreadsheet of the city of Asheville’s affordable and workforce housing rates. Information from the city of Asheville.

On that chart, AMI is “annual median income.”

It’s worth noting that those aren’t the only criteria in play. Two major federal programs that have played a role in the city’s affordable housing strategy — HUD’s low-income housing tax credits and the HOME program — require that rents are based instead on 60 percent of an area’s median income. Such programs figure prominently in the affordable housing developed by non-profits like Mountain Housing Opportunities, with whom the city frequently collaborates.

As the topic of affordability’s heated up, it’s not uncommon to hear comments bounce around on social media and elsewhere that the criteria — especially for workforce rents — aren’t that affordable and that in some cases the city’s just straight-out subsidizing private developers for doing what they would have done anyway. For their defenders on Council and elsewhere, the situation’s dire enough that expanding the housing stock with workforce and affordable units does at least some good.

Staudinger admits in an email explaining the criteria that refining them is a constant effort. For example, he notes, city staff are currently looking into ways to incorporate the cost of transit into considering whether or not housing rates at a particular place in Asheville are affordable.

“Council includes a focus on affordable housing as part of its strategic plan, so I expect that we will delve more into this issue and continue to hone our definition of affordable,” Staudinger writes.

On Tuesday, the latest round in the debate over affordability in Asheville will go before the Council dais. If you’re interested, Council meets at 5 p.m. on the second floor of City Hall.

—

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by its readers. If you like our work, support us directly on Patreon. Questions? Comments? Email us.