The MMIW crisis is at the intersection of racism, sexism and the ongoing violence against Indigenous communities. A glimpse at how one local is part of the efforts to fight back

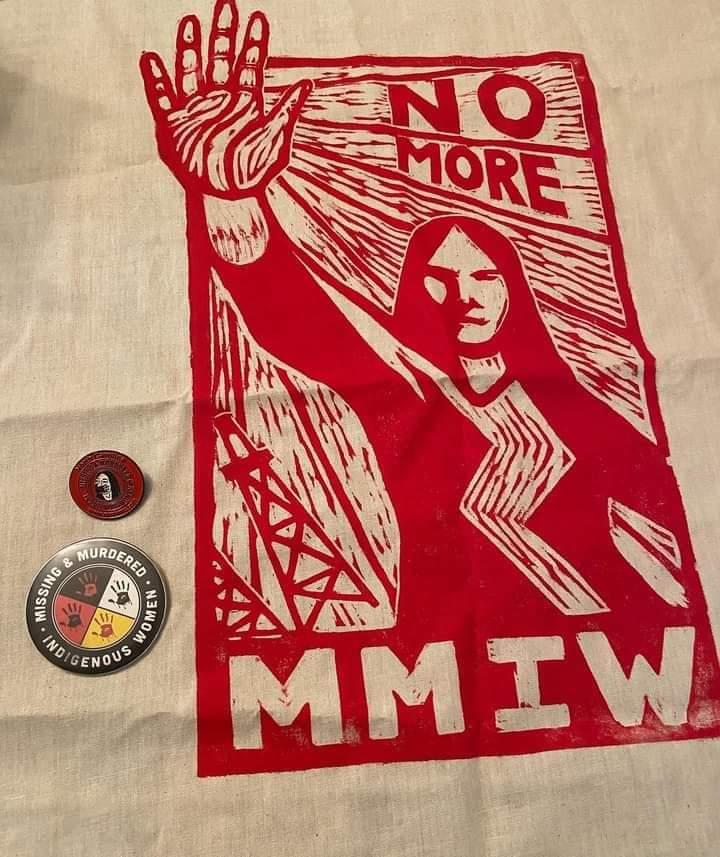

Photo from the MMIW NC Coalition

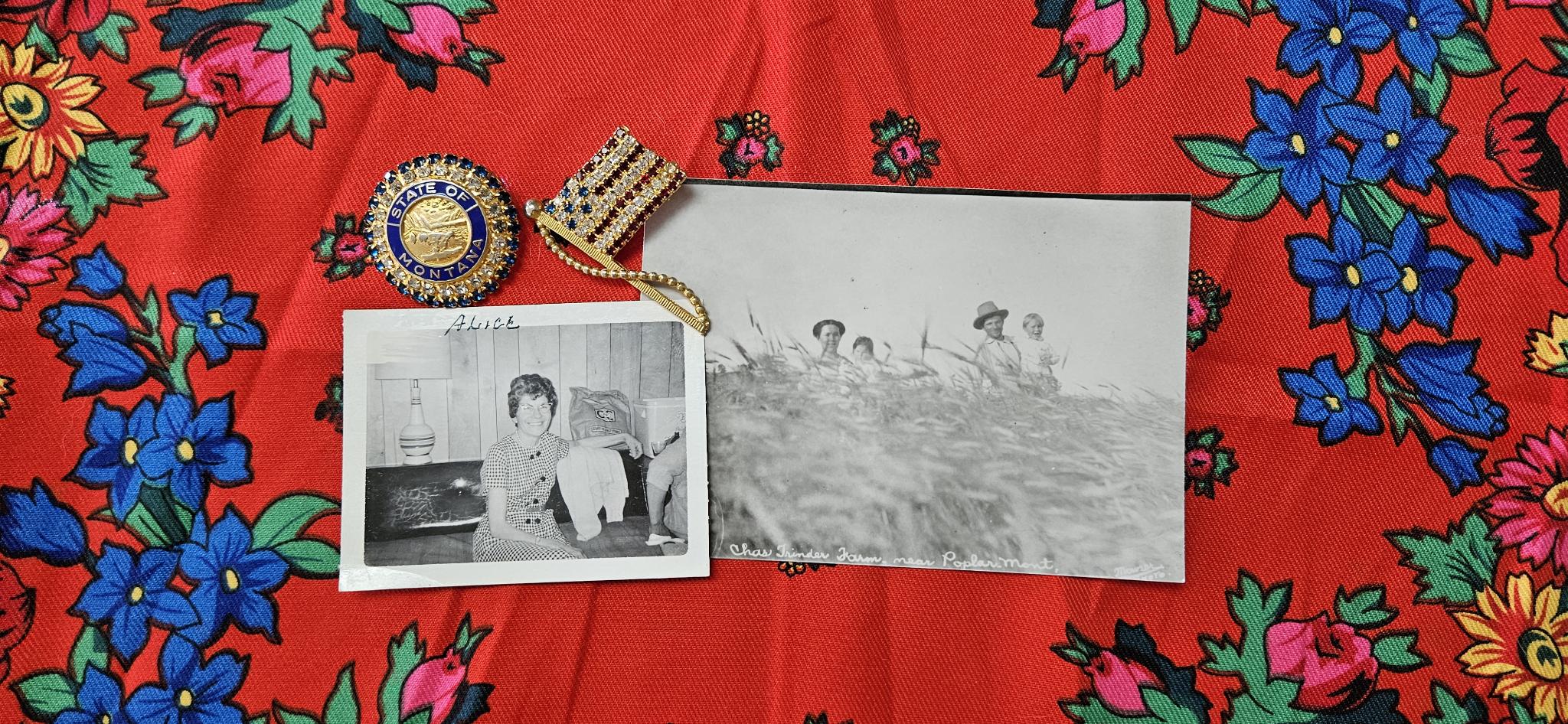

Amber Merideth was raised here in Asheville with the knowledge of her Indigenous heritage, but it wasn’t until the pandemic that she began the journey of reconnecting to a family line she knew little of. Merideth is Assiniboine and her ancestral home stretches through Montana, North Dakota, and into Canada. She has also been publicly adopted by a Dakota elder and is now recognized in the Dakota nation as well.

As Merideth learned more about her home and met long lost family, she also learned the true depth of the crisis of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, or MMIW.

“Indigenous people have had targets on their backs since the age of colonization. Colonizers know if you want to truly bring a strong nation down, you go after the women and children,” she tells the Blade.

“People like to think Indigenous people get free education, free healthcare and even free money. This is the furthest thing from the truth. Our land is held in trust through the BIA, our women and children get stolen, raped or murdered, and we’re pitted against each other through government-installed programs like Blood Quantum.”

There’s more, including food apartheid and ongoing cultural genocide. When we spoke Meredith asked if I knew there were still open residential schools in the U.S.

“They’re in South Dakota and Oklahoma” she said. She mentions the lack of education about Indigenous cultures and how this impacts both white and Indigenous children, and that ignorance is a breeding ground for hate and fear.

She emphasizes the concentration of MMIW where Indigenous land is close to military bases and oil pipelines, and that bodies are most often “dumped” and “found in ways that destroy evidence.”

In a March 2022 hearing by the U.S. House Subcommittee on Civil Rights and Civil Liberties it was stated that in 2020, 40 percent of all women and girls reported missing were Black, Brown, and Indigenous. This 40 percent is in spite of BIPOC women and girls only representing 16 percent of the population. Indigenous women face a murder rate ten times higher than the national average.

A 2016 study by the National Institute of Justice showed that 4 of 5 Indigenous women experienced violence in their lives, with a little over half experiencing sexual violence.

While these rates are staggering, research data shows that national averages hide the extremely high rates of murder against American Indian and Alaska Native women present in some counties comprised primarily of tribal lands,” according to the report. “Less than half of violent victimizations against women are ever reported to police.”

Indigenous women are 1.7 times more likely experience violence than white women, and more than two times more likely to be raped than white women.

But there is also a lot of organizing against these atrocities. The MMIW abbreviation emerged as a hashtag online, though the growing movement is for all Indigenous people including girls, two-spirit, boys, and men.

One of the hardest parts in putting this article together is the absence of data for MMIW. Indigenous people are racially misclassified, ignored by authorities, written off as runaways, and underreported, among other problems. Across the country documents lack the ability to distinguish the cultural nature of kinship and connection to indigenous communities.

Some cases below were given to me by Merideth, and the others I came across as I researched. None of the articles I found linked to each other and few of them mentioned MMIW as the crisis it is.

In North Carolina a key group fighting back is the MMIW NC Coalition and its founder Crystal Cavalier-Keck, of the Occaneechi-Saponi nation. Getting accurate data on the scale of this part of ongoing genocide is one of their main goals. A recent petition sent to the state demands a task force be created to help fight the abduction, homicide, violence and trafficking of Indigenous women in North Carolina. One focus of the task force would be improved data collection and reporting methods.

The annual MMIW NC Coalition conference is Saturday, April 29 in Chapel Hill. Some panels at the conference will discuss domestic violence, human trafficking, and a men’s panel titled “How to get back to Protector.” Speakers include Indigenous activists Norm Sands and Teyana Viscarra, as well as keynote speaker Mary Lyons.

The day before the conference is a virtual race that Merideth has pledged miles to that will raise funds for the coalition. She will begin her trek from the Biltmore Gate House, walk through downtown, to the Grove Park Inn and back. The purpose of the race is to “is to raise awareness, bring solidarity with Indigenous Women, Girls, Two-Spirits, Relatives, victims, grieving families, and individuals working on the frontlines to end this problem of violence against our Indigenous relatives.”

Some of Merideth’s family, on land that’s still at risk of being lost due to colonizing government policies. Photo from Amber Merideth

She reached out to several departments with the Biltmore House trying to arrange beginning her walk at the front door of the historic home. That mansion, still the largest private home in the country, sits on land stolen from the Anikituwagi, or Cherokee. Meredith sought to do this as a symbolic gesture that could show land acknowledgement and help shine light on an important issue facing modern Indigenous people. They didn’t respond.

Merideth plans to do this walk in a traditional skirt, made by her grandmother and a red handprint — the symbol of the MMIW movement — on her face. She hopes the regional significance of the locations she has chosen will help more people learn about the crisis.

Just south of Fayetteville, in Pembroke, Meredith’s friend Jane Jacobs lost her sister, Katina Locklear, both of the Tuscarora Nation, in 2018 just days before Christmas. Jacobs would later learn that her medical records had her listed as African-American; which means her death could still be misclassified in statistical data.

Jacobs, like Merideth, demands better for all Indigenous people.

“Women are sacred,” she tells the Blade, “powerful enough to bring life forth from the spirit world into the physical world.” Indigenous women “need to be protected at all cost.”

As of now, the two men charged with Locklear’s murder in 2018 are still awaiting trial. Other cases from that same area remain unsolved. Such are the cases of Rhonda Jones, a Lumbee woman, and her friend Megan Oxendine, also Lumbee, as well as another friend who is not Lumbee, all found over a few weeks in the spring/summer of 2017.

Those three women all disappeared within the same shorter timeframe and as of this writing, those families still have no answers. There are others as well. In 2015 Sarah Nicole Graham, a Lumbee woman, went missing and her family still has no answers. North of Robeson County, in Chapel Hill, a student named Faith Hedgepeth, a member of the Haliwa-Saponi nation, was brutally murdered and her alleged murderer was arrested in 2021 but has yet to go to trial.

Western N.C, is not exempt. Merideth calls attention to Marie Walkingstick Pheasant, who was found inside a burning vehicle just inside the Qualla Boundary on December 29, 2013. This fire, like so many MMIWs, was intentional.

There has been no movement on that case since Pheasant was found, though a reward for information leading to arrest was increased to $50,000.

Recent years have also seen increased organizing within the Eastern Band of the Cherokee to fight back against these atrocities. Last year the EBCI marked MMIW Awareness Day with a vigil, where organizers declared their intent to organize an EBCI chapter of the MMIW movement.

“That’s one thing that I want to see with us organizing this chapter together is to really support our families of the victims – not just work to bring justice to those that murdered our sisters, but to help these families and to help these children,” Mary “Missy” Crowe told the vigil, according to a report in the Cherokee One Feather.

Also last year three women from the EBCI started the We Are Resilient podcast to directly bring attention to too often-ignored MMIW cases.

MMIW NC and Merideth know one of the biggest hurdles faced is the shortage of consistent, accurate media coverage. One example is the widespread media coverage of the murder of Gabby Petito in 2021 which drew attention internationally, but too often treated her killing as a singular tragedy.

Tai Simpson, director of Social Change for the Idaho Coalition Against Sexual and Domestic Violence and a member of the Nez Perce nation, emphasized in the decade leading to Petito’s disappearance nearly 700 Indigenous women have gone missing from the same area.

Merideth hopes her walk, and the planned walks of others across the state will bring more awareness and more answers for families of all the missing and murdered Indigenous people.

Merideth says she wants to be direct with colonizers:

“We’re still here. Respect us or expect us.”

—

Veronica Coit is birth giver to two, mother to a few and grandma to one. They are a hair stylist by trade; cat rescuer and advocate by passion. Veronica is an award-winning community volunteer who founded Asheville Cat Weirdos and the ACW Emergency Fund, both with the goal of improving the lives of companion animals and their humans in WNC.

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by our readers. If you like what we do, donate directly to us on Patreon or make a one-time gift to support our work. Questions? Comments? Email us.