City hall and the chamber portray a Business Improvement District as inevitable. But a broad array of locals are fighting back against this gentrifying power grab

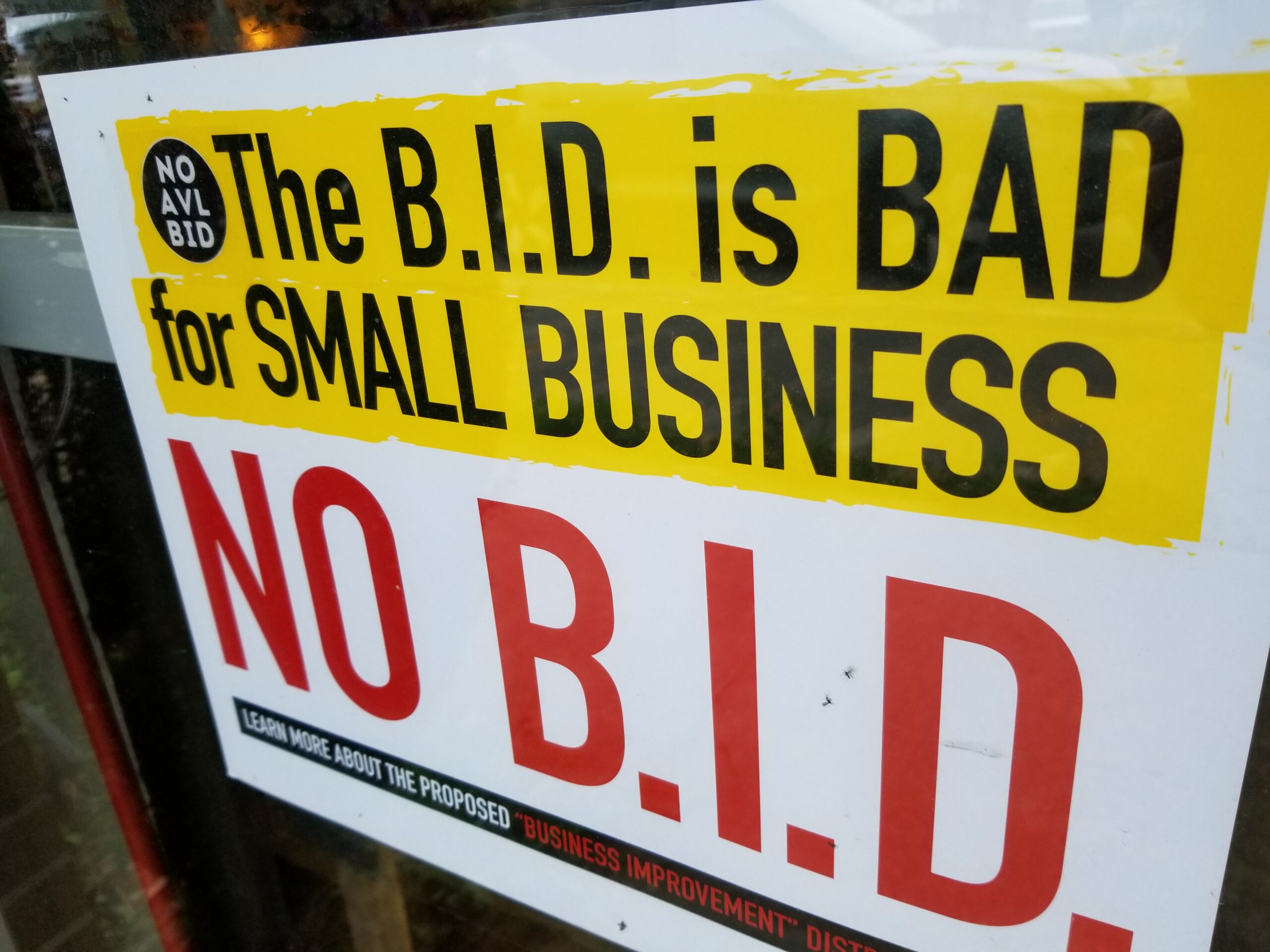

Above: A sign against the BID in the window of Sow True Seed, one of many independent spaces opposing it

Earlier this year a Business Improvement District in downtown Asheville was supposedly a done deal. The proposal was pushed by the Chamber of Commerce, hyped by a mostly compliant media and backed by an extensive marketing campaign claiming it would make the neighborhood “clean and safe.” At the time no city council members or candidates opposed it.

But in early April the public’s attention finally turned to what it would actually mean and what the track record of other BIDs across the country actually looked like.

Locals did not like what they saw.

Past the facade of glossy brochures and stage-managed information sessions the proposed BID is a massive giveaway in public cash to a front group controlled by the chamber and other conservative business owners. They’d tax the whole of downtown — meaning higher rents for tenants — to the tune of over $1.25 million a year. Most of this would go to private security teams (the “ambassadors”) whose role would be to target, in the plan’s own words, “anything deemed out of the ordinary.” The BID’s governing board would be dominated by wealthy property owners. City hall would even pay the chamber back for hiring a private consultant to craft the BID to the tune of $200,000.

Then there were the track records of similar districts throughout the country. Contrary to the rosy view of an uncontroversial “best practice” pushed by business groups, BIDs have an ugly record of civil rights violations, surveilling protests, breaking labor laws and pushing out small businesses.

More and more people saw the BID for what it was: a power grab by the wealthy, blatant even by Asheville’s standards. Over the next few weeks opposition boiled over from government meetings to local sit-downs to online organizing.

Now, heading into the first vote on the proposal at tonight’s Asheville city council meeting (it also has to pass a second vote June 11) even its boosters are grudgingly admitting the BID now faces an uphill battle in the face of an increasingly mobilized public.

Here’s a look at what changed, and some ways locals are fighting the BID.

The spirit of the city

As March turned into April more locals were becoming more aware of the Business Improvement District and the potential threat it poses.

An in-depth April 11 article from the Blade delved into the details of the proposed BID and the damage done by others around the country. While our coverage was far from the only discussion about the BID taking place, the piece got an unusually high amount of attention as it circulated over the coming days and weeks. The public wasn’t buying the chamber’s talking points and wanted more information.

On April 14 city council member Kim Roney, who’d previously indicated at the April 9 council meeting that she might consider supporting the BID, openly opposed it in a public statement.

“If we raise taxes for a BID, the burden will disproportionately fall on renters, including small businesses,” Roney wrote. “Like the Tourism Development Authority this is another unelected board overseeing tax dollars with majority of seats for the largest property owners.”

Grassroots efforts were also ramping up. Already hit hard by skyrocketing rents in one of the least affordable cities in the country, locals were justifiably angry about a proposal that embodies the worst of Asheville’s gentrification.

On April 16 the Sunshine Labs organization, composed of longtime local government transparency advocates, released a blistering analysis in the form of an open letter. They sharply criticized the secrecy of the BID process and the predominance of seats reserved for wealthy elites on its governing board.

“The current proposal to establish a BID in downtown Asheville would create yet another unelected board systematically designed to serve the interests of the few,” they found.

The anarchist Firestorm cooperative, who played a key role in organizing resistance to the previous 2010s push for a downtown BID, denounced this one too and urged locals to fight back.

“Many of us feel that we’ve reached a new low, in which our voices are not being heard and Asheville is more unlivable,” their statement against the BID reads. “What comes next is consequential: we can work to protect the vibrant spirit of our city while fighting to correct historic and ongoing injustices; or, under a ten-year BID term, we can watch as a few power brokers, insulated from democratic controls, transform our urban spaces to suit their needs.”

The BID was marketed by the chamber and others as a demand by “downtown workers,” thought it was lawyers, realtors and top-level managers touting it in public. But as word spread throughout early April service workers did organize around the issue — against the BID.

“A couple of our members reached out and said they were opposed to the BID for various reasons and we put it to a vote among the dues-paying membership,” Jen Hampton, lead organizer for the Asheville Food and Beverage United union, tells the Blade. “Overwhelmingly they chose to oppose it publicly.”

The initial result was a powerful April 19 declaration from Asheville FBU against the BID, blasting it as an attempt to “turn downtown into a glorified outdoor shopping mall controlled by elites who only care about lining their pockets even more.”

Plenty of independent business owners also saw in the BID not increased prosperity but a danger to their livelihoods and communities.

“I was told over and over ‘everyone downtown wants a BID,’ and that it was ‘inevitable,’” Madison Jane, owner of the Haus of Jane salon, tells the Blade. “Yet the more people I talked to that didn’t have a direct affiliation with its proposal or interest in the financial benefits that comes with managing the BID knew little to nothing about it.”

“I can’t get on board with something that claims to support the community when the community as a whole has little to no say in who and what it’ll support. I don’t believe corporate redlining and privatization of our taxes and public spaces addresses the key needs for a thriving city.”

In everywhere from conversations among neighbors to social media, opposition to the BID grew in the coming days. At the beginning of the month the upcoming April 23 city council hearing must’ve looked like just another opportunity for BID supporters to continue their parade to power. Council had even obliged the chamber by moving to an earlier meeting time before many locals got off work, changing the venue to the civic center and planning to limit public comment to a single hour.

All this made it more likely that the wealthier BID supporters could shut out the growing number of locals against it. Given city hall’s track record of arbitrarily changing rules to favor the gentry, that was probably the intent.

But as the hearing drew closer even the chamber started to feel the heat. The weekend before that meeting they suddenly changed the proposal: lowering the property requirements (from $1.5 million to a mere $500,000 in holdings) for some of the seats on the BID board, eliminating a seat for the TDA and shifting the BID boundaries to leave out part of the historically Black East End neighborhood.

These changes were minor, more re-arranging the deck chairs on the Titanic (or, given the chamber’s politics, the Hindenburg) than any actual shift.

If the chamber thought it would appease locals, they were very wrong.

‘We have a whole hell of a lot more to lose’

Even in the extensive history of Asheville city government’s incompetence and petty disdain, the April 23 meeting stands out. Some public hearing notices said the BID hearing wouldn’t start before 7 p.m. despite the 4 p.m. meeting time. Others told locals to get there by 3:30. Before the meeting even began dozens had already signed up to speak, most about the BID.

As if all that wasn’t enough Vice mayor Sandra Kilgore — who chaired the meeting in Mayor Esther Manheimer’s absence — and council spent much of the first half of the meeting debating on how they should even hold the hearing. They considered limiting speakers to two minutes instead of the regular three and whether to cap public comment at an hour or not.

To working class locals this, combined with the wall of cops that greeted many of them upon entering the civic center ballroom, made for a deeply confusing and intimidating environment.

“What’s happening here tonight shows you don’t really care about the voices of the people,” Grace Barron, a local against the BID, told council during public comment. “You said we had to be here at 3:30, so most people working a 9-5 job are not going to be able to access it. Now you’ve moved the comment back to 7 p.m. You kind of make up rules along the way; we don’t even know how long we’re going to be able to talk for.”

Then there was the contempt. Kilgore, despite leading a round of applause for police officers during a proclamation at the beginning of the meeting, falsely asserted that clapping was banned when people started to criticize the BID. Council member Maggie Ullman chided the crowd for being “divisive” for, heaven forfend, criticizing the chamber and the police.

She claimed the chamber’s BID proposal was “an offer of help” that the city shouldn’t refuse. By contrast Ullman spent considerable effort last year trying to make actual help — in the form of locals directly giving cash or food to the poor — literally illegal. She failed due to public outrage.

City hall has repeatedly cracked down on community efforts to feed and shelter the homeless and currently faces civil rights lawsuits for secretly banning protesters and mutual aid volunteers from parks. Apparently something only counts as help when it means giving a group of conservative business owners $1.25 million a year in public tax dollars and another $200,000 for their consultants.

To top it off Ullman insultingly implied that BID opponents hadn’t researched the issue.

Locals weren’t having it. Service workers, teachers, renters, artists, elders and even plenty of business and property owners all still showed up and opposed the BID.

“You want to know why non-business owners are upset and distrusting? It’s because we have a whole hell of a lot more to lose,” Bree Snyder said. “We are fighting for our living and for our literal homes, as we cannot afford to pay rent in this town. They are fighting for extra profits on top of the profits they already make off our backs.”

“We stand firmly against the Business Improvement District,” Hannah Gibbons, one of the worker-owners of Sow True Seed, told council. “The cost of living and working in Asheville has risen exponentially over the last few years.”

“We have concerns that the additional tax will make it more expensive for our small business to continue to grow and operate out of this city,” Gibbons continued. “We strongly oppose an additional tax that will allow for increased and privatized policing and surveillance of our neighbors.”

Even some of the downtown figures who’d supported the early 2010s BID push opposed this one.

“It has too many unresolved elements, too little community input and a false sense of urgency to get it done,” Susan Griffin, who chaired the earlier effort, said. “A bad BID is worse than no BID at all.”

She emphasized that the effort had, from start to finish, been run by the chamber while “residents, tenants and other stakeholders have not been invited to join this conversation” and that council should “send this back to the drawing board.”

Council has an extensive track record of ignoring the public. But this much anger, for this long, was having an effect. Council member Sage Turner, previously a vocal supporter of a downtown BID, announced at the hearing that she was now neutral on the idea. Notably Roney and Turner are both running for re-election this year.

“I feel like it would be a mistake for council to push forward a flawed and incomplete proposal just because the chamber says so,” Patrick Conant of Sunshine Labs said.

“There are over 4,500 cities in the United States and the vast majority of them don’t have BIDs,” Libertie Valance, of the Firestorm cooperative, said. “Across the country communities are rejecting this form of neoliberal urbanism and its noxious track record.”

“Here in Asheville we have our own history of skepticism towards this nonsense. Rather than being a new idea, the BID is an extension of an old idea: the idea that downtown exists for, and should be controlled by, commercial landowners and the rich.”

“’Clean and safe’ has been a dog whistle against marginalized communities for so many decades,” educator Kyle Teller pointed out. “The rising costs of living and working in downtown Asheville continue to highlight and exacerbate our city’s deeper issues: a lack of living wages and affordable housing in a tax and rent-hike driven city.”

“I could be one of those people that is labeled as ‘out of the ordinary’: I’m transgender and I struggle with mental health,” another speaker said. “A lot of us are passionate about this because we care.”

“This proposal is a thinly-veiled attempt to clear out the riff-raff,” a downtown service worker against the BID told council. “The shift meals I’ve given to people on the street have been a greater contribution towards this community than that proposal could ever hope to be.”

In the end speakers against the BID overwhelmingly outnumbered its supporters, 39 to 11. Perhaps for this reason, council backed off limiting public comment to a single hour rather than face a roomful of angry locals. If you want to see the sheer array of locals against the proposal, Firestorm put together a super-cut of all the anti-BID speakers.

Even at a place and time set up to cater to BID backers they were still heavily outnumbered.

The official presenters of the BID proposal were Larry Crosby, manager of the luxury Foundry hotel and Eva Michelle Spicer, one of the owners of Spicer Greene Jewelers, previously known for its blatantly misogynistic billboard.

Besides them so few speakers showed up to support the BID that we can easily list them all:

Steven Lee Johnson, a landscape architect and downtown property owner.

Scott Fowler, owner of Brucemont Communications, a p.r. firm whose clients include the Biltmore Company and the Tourism Development Authority.

Sherree Lucas, director of the Go Local Asheville business group.

Radd Nesbitt, representing the Hatteras Sky real estate development firm, whose focus includes hotel investment.

Austin Walker, a real estate broker specializing in “office and industrial properties.”

Rick Bell, executive director of the Asheville-Buncombe Hotel Association. One of his main reasons for backing the BID was that it will push downtown’s already sky-high property values even higher.

Elizabeth Button, of Asheville Independent Restaurants, a business group representing the interests of restaurant owners.

Laura Webb, owner of an investment and “wealth management” firm who said she was “a little uncomfortable walking downtown.”

J.B. McKibbon, heir to the McKibbon hotel group, who bragged that the company “is a large property owner” and hoped that the BID would help deter protests like those outside his organization’s hotels in 2020.

Notably McKibbon also touted his involvement in Chattanooga’s BID, which he claimed was not contentious. This is untrue. That BID faced heavy opposition from the city’s NAACP and Black locals who saw it as an attempt to concentrate more power in the hands of wealthy, white property owners.

Hayden Plemmons, executive director of the Asheville Downtown Association, who’s working directly with the chamber to push the BID and would have a role in appointing its board.

Casey Gilbert, head of the PowerWith consulting firm whose clients include chambers of commerce. She’s also the former CEO of the BID in Portland, Maine.

It’s a revealing list, because these aren’t just business and property owners but a narrow upper crust even among them.

That’s who’s behind the BID. That’s who it will serve.

Indeed, the facade of excuses for the BID fractured badly during the hearing. Lucas claimed that independent businesses were backing the proposal, but almost every small business owner that spoke at the hearing strongly opposed it.

Button asserted that restaurant workers supported the BID. But just moments before she spoke Hampton, speaking for a literal services workers union, condemned the proposal as “pushing out the working class.”

The fight continues

“We call on Asheville City Council to fully cease any further action toward the creation of a downtown BID, and further,

We call on Asheville City Council to invest instead in community-led, democratically accountable initiatives for downtown that prioritize equity and the needs of the many, instead of the desires of a few.”

— Petition from Community Members Against the BID to Asheville city council, April 29

The first up or down vote on the downtown BID proposal took place at the Downtown Commission on Friday, April 26, a few days after the city council hearing.

BID proponents might have hoped for something of a political comeback after the public thrashing they received at the council hearing. Plemmons and Spicer even sit on the commission, though they had to recuse themselves from voting given their direct interest in the BID. The commission’s generally controlled by the kind of gentry — architects, elite consultants, wealthier business owners — that are its main constituency.

Instead a motion proposed by Spicer to endorse the chamber’s BID proposal failed to even get a second. A heavily-amended BID endorsement that would’ve required stripping property requirements for its board, more public input and limits on the powers of “ambassadors” stilled failed 4-4.

Even among the more well-off who might support some form of BID, the chamber’s proposal has encountered skepticism and outright opposition. On an April 29 episode of The Overlook podcast, three downtown business and property owners — including two involved with the previous BID effort — took this one to task as an un-transparent power grab by the chamber.

Among a wider coalition of locals mobilization against a BID — period — gained increasing traction. On April 29 the Community Members Against the BID coalition launched an online petition, titled “Don’t Sell Downtown Asheville to the Highest BID-der” rejecting the idea entirely. Within a week it had gained over 500 signatures — unusual for a local issue — and as of press time had over 800.

As the effort’s gained momentum those who portrayed the BID as an inevitable civic reform have scrambled to play defense. In a recent column Asheville Watchdog‘s John Boyle, who’s routinely acted as de facto public relations for the chamber’s effort, dismissed the widespread opposition to the BID as based around aesthetics, like the polo shirts ambassadors would wear (no, I’m not making this up).

This is, to put it mildly, false. Those against the BID have extensive studies, research and direct experience backing up their opposition. The petition included a list of eleven major points against the proposal, complete with links. Its debut saw opponents of the BID put up a whole page with even more information.

The coalition behind it included the Asheville FBU union. Hampton tells the Blade that many service workers are from — or closely connected to — populations that the BID will threaten.

“That’s Asheville, we are ‘out of the ordinary,’” she says. “We’re worried about our unhoused neighbors, we’re worried about our trans neighbors. Anybody that is not ‘normal’ or ‘ordinary,’ anyone the Business Improvement District folks don’t want the tourists to see.”

“We love how different and unusual and unique we are. We worry about the effect this will have on everybody that doesn’t look like the business class.”

This isn’t speculation, as Hampton has seen the damage wrought by a BID up close in her hometown of San Antonio, Texas.

“It’s entirely ruined the vibe of downtown. It used to be a whole bunch of independent stores and restaurants. Now it’s just a bunch of national chains,” she says. “In the BID it’s super-sterile, it feels like a shopping mall. I didn’t see any locals there.”

Hampton also emphasizes BIDs’ long record of labor law violations. Block by Block, a company that was brought in to help craft the chamber proposal, is currently facing a bevy of lawsuits alleging it did just that.

For Jane, gentrifying efforts like the BID tie into Asheville’s long history of city officials and powerful business interests trying to push out everyone who isn’t white and wealthy. She sees ominous parallels with the “urban renewal” that devastated local Black communities.

“I don’t believe they have everyone in mind when pitching a ‘clean and safe’ downtown. I’m worried that it means cleansed of people they deem unworthy of taking up space, which usually points to underestimated communities,” she tells the Blade. “Just like urban renewal, Jim Crow segregation and redlining, I’m afraid if a BID is passed history will repeat itself and the devastation of its impact will be felt for generations.”

“Nothing about a BID addresses fundamental human needs to survive that many people throughout Asheville are struggling to attain,” Jane continues. “Healthcare, living wages, affordable housing, education, and infrastructure maintenance to name a few. That’s where I believe our taxes and efforts should be focused before ever considering handing our tax dollars over to private entities that only have their needs in mind.”

In addition to the threat posed by the BID itself, the fight against it has also galvanized larger anger against gentrification. Hampton notes that it’s telling that AIR and other business groups are claiming to speak for downtown workers when they support the BID, even as actual workers loudly oppose it.

“I have not talked to a single service worker who thinks the BID is a good idea,” she emphasizes. “I don’t think the restaurant owners’ association can really speak or represent the voices of the workers, because even if they were to have a conversation with a worker, there’s the power dynamic. A worker is not necessarily feel comfortable with sharing their actual views on this issue with an owner who supports it. You can’t really speak your mind to your boss.”

Jane, Hampton and others around the city didn’t stop with an online petition. Locals have gathered to bombard officials with letters, to canvas and organize others against the BID, laying the groundwork for further efforts to fight it. They even launched a new slogan, “The BID is CRAP,” with the last acronym standing for Corporate Redlining and Privatization.

You can hear some of the organizers of the coalition against the BID, including Jane, speak about their efforts in a recent episode of The Final Straw radio program.

At the heart of the widespread outrage driving this opposition this is the simple fact that the people of this city absolutely do not want a Business Improvement District and that a small cartel of the wealthy is trying to inflict it anyway.

Tonight city council is set to take its first vote on the issue. Despite the signs of growing opposition, one should still never put an ounce of faith in politicians. Council goes against the public will all the time. Anyone fighting the BID, and the larger gentrification it embodies, should be prepared for the long haul.

But in a matter of weeks locals across the city have already thrown a wrench into the plans of the chamber, turning a done deal into a desperate scramble.

So beneath the contempt from city hall and CEOs are the unmistakable signs of fear. The fight against the BID is a serious, grassroots challenge to this city’s status quo, where a handful of wealthy “stakeholders” run things to the detriment of everyone else.

Like the BID, there is nothing inevitable about their power and, increasingly, the rest of us know it.

—

Blade editor David Forbes is an Asheville journalist with over 18 years experience. She writes about history, life and, of course, fighting city hall. They live in downtown, where they drink too much tea and scheme for anarchy.

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by our readers. If you like what we do, donate directly to us on Patreon or make a one-time gift to support our work. Questions? Comments? Email us.