The truth about the decades-long fallout from racist government programs offers some harsh reminders — and important lessons for Asheville today.

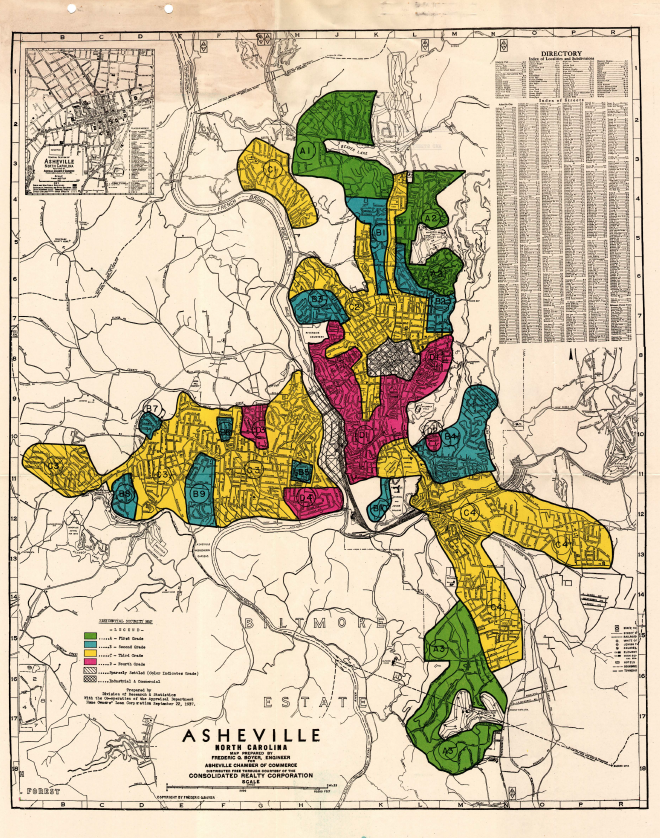

Above: The 1937 HOLC map for Asheville. The areas in red, most of them African-American, were designated “unsafe” for investment.

Over the past week, I’ve been incredibly pleased to see people read and respond to Red lines, our in-depth story on how a racist government program in the 1930s guided the “urban renewal” of the 1950s and 70s that had a devastating effect on Asheville’s African-American communities. The effects, sadly, still haunt the city today.

History is important not just because of the need to not repeat past evils, but because without it we can’t have an accurate idea — horrors and all — of how the place we live got the way it did. Without history it is far too easy to succumb to prejudice, lazy generalizations and a host of other things that will easily march people to disaster.

I can’t count the number of times I’ve heard, for example, Asheville’s lingering, de facto segregation waved off as just a matter of “culture.”

But it wasn’t culture that demolished the homes on Hill Street. It wasn’t culture that rolled through Southside and kicked thousands out. It wasn’t culture that put a highway smack dab into the Burton Street community. It wasn’t culture that pushed many of the remaining people into housing projects.

It was power, wielded by people. Power abused in the service of bigotry and bad ideas, because thousands of Ashevillians were considered expendable and the neighborhoods they’d built against considerable odds “blighted.”

The “real estate desirability” scale that economist Homer Hoyt used to shape redlining in the late 1930s seems like a horrific artifact of the prejudices of another time, with its warning against mortgages for “Negroes,” “Mexicans” (a catch-all term used for Latinos) and “Russian Jews of the lower class.” But it’s worth remembering that people with power and education didn’t just believe these lies but acted on them for decades, even after it had faded into the background.

It’s a warning against the view that the problems of our city — or any other, for that matter — are just the products of sincere people trying to do their best in the face of impersonal forces, things that can be solved through education or consensus-building to get everyone on the same page.

Evils like redlining are conceived and carried out by actual people to gain an advantage and use power to hurt others. The people responsible didn’t need educating. They needed to be stopped, period. For society to thrive, some views need to win and others need to lose, and redlining is a reminder of the stakes — in this case on a national scale — when bigots win.

Additionally, the wholesale destruction of key Asheville communities — and the betrayal of many of its citizens — was conceived, carried out and continued by educated people using official-sounding language to cover up what amounted to no more than prejudice and delusion, and elected officials went right along.

This is also a harsh lesson in that, because one common thread from the 1930s to now is the huge amount of power the Council-Manager system (and the state and federal governments that tie into it) gives to the appointed bureaucracy (during urban renewal the city manager essentially ruled the city). Hoyt wasn’t just an economist who believed terrible things, he was among the pioneers of a new type of urban governance that was supposed to move more authority into realm of professionals using “scientific” ideas.

While redlining and urban renewal are extreme examples, they are instructive that professional managers can be just as horrible as anyone else, especially when unchecked by a robust local democracy.

Because someone is knowledgeable about planning, for example, doesn’t mean that they’re not a bigot — or that they don’t believe some really stupid things. In historian Barbara Tuchman’s classic The March of Folly, about how governments end up crashing into disaster, she diagnoses the problem with over-relying on management, noting that without check from the larger society “bureaucracy, safely repeating today what it did yesterday, rolls on as ineluctably as some vast computer, which, once penetrated by error, duplicates it forever.”

So, it’s all too easy for the inertia of past evil to continue again and again. Reinforcing the racist lines drawn up in 1937 can eventually just become “building off existing infrastructure” long after the people who made the maps are dead.

Rather than vague forces, “culture” or “the way things are,” the story of redlining reminds us that cities are made — or ruined — by human beings. Other humans can choose, aggressively, to take a different course, to refuse to let the horrors of the past continue to dictate a city’s future. The past lingers only until other people successfully fight its influence.

Yes, 1937 is a long time ago. But it’s 2014 and Burton Street is still facing an interstate. Southside’s inhabitants still fear, according to a recent report commissioned by the city itself, “another wave of displacement.”

Talking about learning from history’s mistakes is one thing. Doing it is something else. In the coming years, we’ll see which path Asheville chooses.

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by its readers. If you like our work, support us directly on Patreon. Questions? Comments? Email us.