Behind the controversial definition of ‘workforce housing’ and the larger debate over local government’s power to solve Asheville’s housing crunch

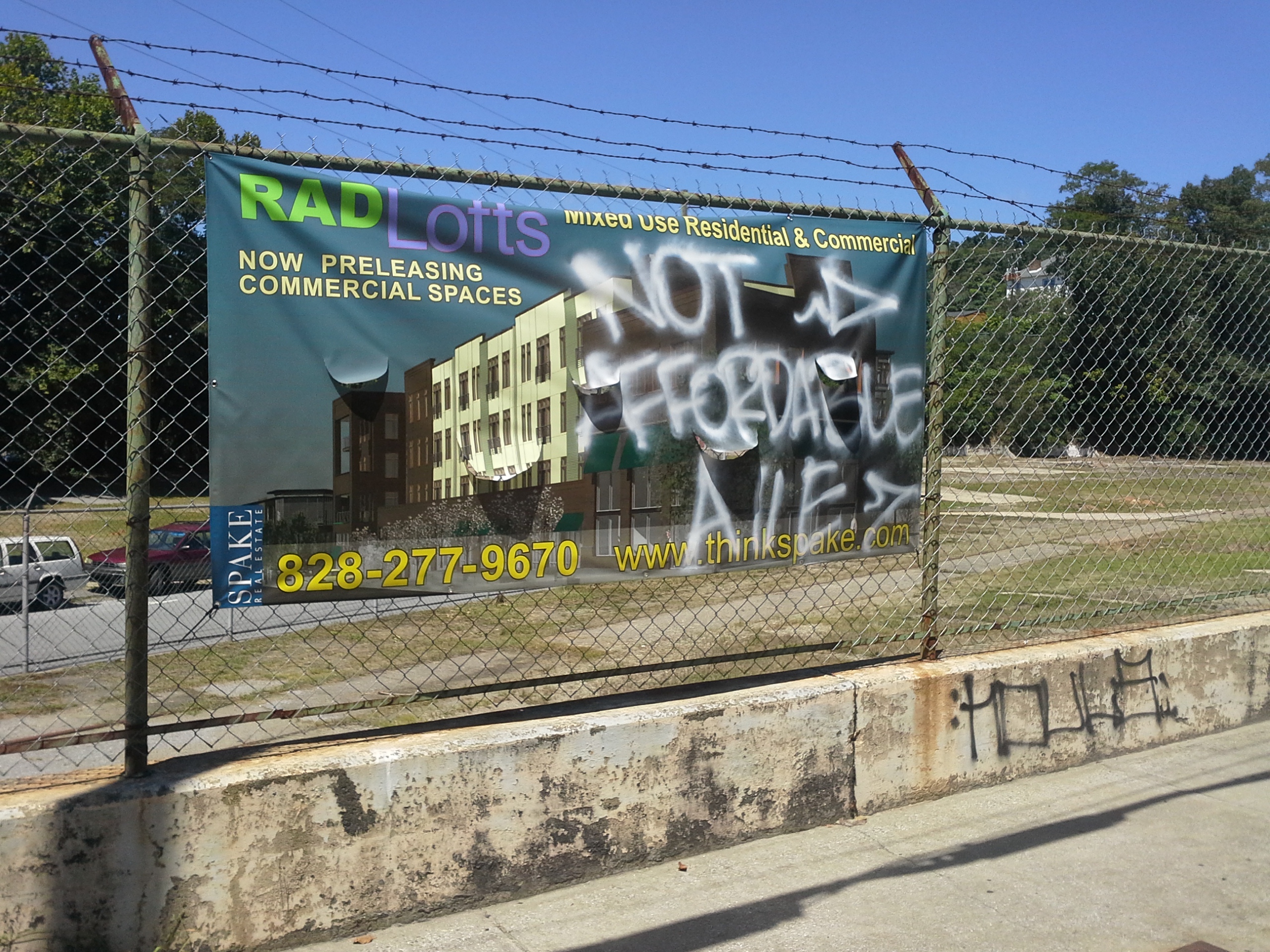

Above: The site of the future RAD Lofts development in September, with dissenting graffiti painted on its sign.

“Workforce housing” is back in the city news again. This perhaps shouldn’t be surprising. Asheville has a major housing shortage and rising rents. City leaders have labelled it a crisis. Meanwhile, developers pushing for incentives claim that they’ll solve some of that shortage, if the city will give them a tax write-off.

Critics, including some on Council, see granting substantial incentives for “workforce” housing as not providing enough units that are genuinely affordable for Ashevillians.

We’ve been here before. Late last summer, controversies over two developments seeking incentives for “workforce” housing also caused some major local debates. Then, the Blade ran a piece laying out how the city defines those terms — there’s a lot, as we’ll delve into shortly, but in a nutshell “workforce” housing is allowed to have higher rents than “affordable” housing — and some of the controversy over those definitions. Last Tuesday, the developers of the RAD Lofts — one of the developments that also came up last year — came before the city again, once more seeking an incentive level above what city policy allowed them. They received those incentives, in a split vote on Council, but not quite as high as they had requested. The vote revealed divisions on Council about how to deal with the city’s housing crisis and how hard a line the city should take on demanding lower rental rates.

The title of “workforce housing” has also come in for some criticism as a good portion of Asheville’s workforce makes well below the income level necessary to afford those rents.

So what’s behind this debate? What exactly is “workforce housing” and why do incentives for it attract so much controversy from graffiti and Facebook forums all the way up to the Council dais? How does it relate to the larger debate over a major civic crisis and what role local government can or should take in solving it?

The city has two criteria of housing it offers possible incentives (of differing varieties) for: “affordable” and “workforce.” Both are based on the median income for different household sizes for the area, then on rents that won’t result in someone of that income level paying more than 30 percent of their pay in rent. If people pay more than 30 percent of their income in rent, they’re considered “cost-burdened” according to federal criteria; their rent or mortgage is eating up enough of their income to make their finances considerably more difficult.

“Affordable” rates are intended as workable housing for households making 80 percent of median income or less, while workforce covers people above that, sometimes well above it. In Asheville’s case, “workforce” can cover households making up to 120 percent of the median income.

When those numbers are crunched, this is what the city comes up with for “affordable” and “workforce” rents:

Then things get a little more complicated. Affordable housing rates are tied to criteria set by the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development. This is because, in part, cities receive grant funds from the federal government to try and provide more housing at this level. In Asheville’s case city government also tries to add more such units through its own programs like the affordable housing trust fund.

But “workforce housing” doesn’t have any such federal direction: local counties and cities set their own criteria, and what local governments consider “workforce” rates can vary widely.

Why is that? Jeff Staudinger, the city’s Assistant Director of Community and Economic Development and its point person on affordable housing, says that “workforce” level-housing becomes more important when a city, as Asheville does, has a housing shortage that starts limiting supply even for those making at or above the median income.

“People have found throughout the country, and certainly here in Asheville, that the need for those who have greater incomes is still significant when it comes to affordable housing,” he says. For example, the recent Bowen report on the extend of Asheville’s shortage found that Ashevillians making up to $70,000 a year were also having trouble finding housing due to the severity of the area’s need. “Part of it is a recognition that housing, especially housing for which people will spend less than 30 percent of their income, runs through a broader gamut of income ranges than what’s defined by federal programs.”

Because those shortages are different in different areas, each ends up coming up with their own limits and guidelines. Staudinger notes, for example, Buncombe County has different criteria for “workforce housing” than the city.

“It goes back to ‘what are the conditions on the ground in the community,'” he says and after research “we decided, and Council agreed, that 120 percent [of median income] was a reasonable standard for this community.”

The main ways the city incentivizes “workforce” housing are by considering it as a criteria when allowing a zoning change for a larger project to go through and through an incentive formula that can allow developers tax write-offs based on providing affordable housing, workforce housing, development near transit lines and other goals in a development they propose. Council, staff and developers have all said that formula is in drastic need of an update, something developers like the RAD Lofts’ Harry Pilos have used to push for a higher tax write-off than the current policy allows.

Because it subsidizes housing for people making, in some cases, above the median income, the idea of the city giving incentives for such housing has come under fire as simply a way to subsidize developers doing what they already plan to do anyway, without serious addressing the area’s need for housing that people can afford on Asheville wages.

“That is an astute and reasonable question for people to ask,” Staudinger says when asked about those concerns and criticism. While “affordable” rate units are needed throughout the city, a challenge with figuring the need for “workforce housing” is that it can vary drastically from neighborhood to neighborhood, he claims.

“One of the hard things is assessing this relative to the location of a particular development as we try to create this one or two sizes fits all solution,” he adds. “Would a development in a green field that wasn’t necessarily accessible by transit have the same level of market and pricing demand — and cost — as RAD Lofts would? I think the answer is no.” In neighborhoods where there’s considerable demand and development is expensive, he asserts that incentives for “workforce” housing can serve to ensure some diversity of housing in developments that might otherwise be entirely out of reach for all but the wealthy.

But due to concerns about the “workforce” rate, he said, he and others on staff are in the process of redrawing the city’s tax incentive policy to encourage more “affordable” rate units and place less emphasis on “workforce” housing.

“We’re constantly listening to feedback from Council and the public,” he says. “We’re feeling more on the staff level that we’re going to be more focused on affordable, we’re really going to look at increasing the score for affordable housing and while not discounting the workforce element, really trying to incentivize those rents at the 80 percent of the median income level.”

Courses of action

For a Council that often votes in unison, the debate over “workforce housing,” how much leeway developers should get and how to deal with the city’s crisis has become a point of increasing contention, and is a key part of a larger public debate about the powers and limits of local government to deal with a pressing issue.

Earlier this month, a lack of affordability was among the concerns that led to a rare 4-3 vote in favor of approving the Greymont Village Apartments. The narrow majority in that vote — with Vice Mayor Marc Hunt a particularly vocal advocate — asserted that the housing shortage is dire enough that even projects that aren’t ideal need to get the city’s stamp of approval. The latest round of RAD Lofts incentives passed 5-2, with Council members Gordon Smith and Cecil Bothwell, dissenters in both that vote and the approval of the Greymont apartments, both asserting that the city should take a harder line on doling out incentives to projects mostly comprised of “workforce” housing. Meanwhile, supporters of the RAD Lofts incentives again asserted that the crisis was dire enough to go above and beyond the city’s old rules, though not as far as the developers wanted.

Part of the reason for this debate is that while state law does place some limits, development is actually an area cities have significant power over.

But cities in North Carolina can’t pass a law, for example, establishing rent control. They also can’t require regular inspections of rental housing due to a 2011 state law and instead can only inspect when a tenant files a complaint, though Asheville ended regular inspections, at the urging of local realtors and landlords, eight years before the state did.

City leaders note these limitations and the tight budgets and limited resources Asheville faces. In such a clime incentives are, the argument goes, one of a limited number of tools local government can use in the face of nearly overwhelming pressure from markets and limits placed on cities in this state to impose more definite requirements. Local officials can also point to studies like the “report card” last year that showed Asheville’s government exceeding others in the state in creating units of affordable housing through government efforts due to the use of grants, incentives and programs like the housing trust fund.

At the same time the cost of housing continues to rise, especially as wages stay stagnant, and the numbers created fall short of what multiple studies — most recently the Bowen report — say is needed. In a meeting last month of Council’s own Housing and Community Development committee, members admitted that the situation was dire. Smith noted that “with the current tools we have we can not meet the need” and Staudinger observed that the city’s policies had created “relatively low numbers” of affordable housing units in recent years when compared to the rising demand.

At that meeting, committee members and city staff discussed zoning changes, more city funds directed to affordable housing, new rules allowing more apartments near existing homes, using city land for housing and new partnerships with the county, among other steps, as some of what they believed they could do to address the issue. A number of the suggestions came from a report from the city’s Affordable Housing Advisory Committee.

Those debates and tensions make how to resolve the housing crisis — and what local government can and should do — a major issue as elections for three Council seats approach.

Robin Merrell, an attorney for Pisgah Legal Services and a longtime affordable housing advocate who’s served on city committees and crafted reports on the issue, observed in a recent interview with the Blade that the situation is the worst she’s seen.

“There’s just nothing available anywhere,” she says. “What is available seems to be pretty substandard.”

Recent years, she notes, hit Asheville with a one-two punch when it comes to affordability: construction came to a halt during the recession but when things ramped up again, new housing was targeted towards the wealthy than the workforce.

But Merrell asserts that there are significant actions local government can — and must — take.

“There should be a bond referendum, density should be increased in every zoning district in the city and I don’t mean add a couple units, I mean double or more,” she says. “There has to be this very public commitment by the government that they’re going to have affordable housing. They’ve got to put their money behind it too.”

Hence the need for a bond, she says, as “small contributions are not cutting it, they’re not getting us where we need to be.”

As for the need for density, she said an increase there, to be effective, would need to come with a requirement that some of the new units are affordable.

That’s a policy known as inclusionary zoning. It’s a topic of some legal debate, but two municipalities in North Carolina, Chapel Hill and Davidson, have such a requirement on their books. Chapel Hill’s has been in place since 2010. During the April meeting, city legal staff noted that Davidson’s currently in court defending its ordinance, and warned the city against adopting such a measure. Notably, the same staff were cautioning against such a policy even before the Davidson court case began.

Merrell notes that even if staff and Council won’t go for such an ordinance because of fears they might end up having to fight a court battle, there’s still more the city can do to put some teeth behind its affordable housing goals, particularly by placing stricter limitations on any housing proposal that doesn’t include a significant amount of affordable housing.

“The biggest is conditional use; putting conditions on development that are then taken away if affordability is included,” she says.

She also says that it’s time for the city to be far more aggressive in dealing with landlords who refuse to keep rental properties in good condition and asserts that despite state limitations, that can happen at the local level.

“There have been changes in the law, there’s also been a change in the city’s way of dealing with rental housing, what was before a hands-on approach has turned into a very hands-off approach and the people who are paying the consequence of that are the low-income renters who call the city for relief when their landlords won’t fix anything and aren’t getting it,” Merrell notes. “If the housing code is a priority for them, they’ll put the funding into that department that it needs. If it isn’t, things will continue the way they have.”

But Merrell also notes that from experience, some of the changes, especially density and ordinances pushing hard for affordable housing, will involve significant local political battles. Specifically, they’ll face opposition from neighborhood groups in wealthier areas “that don’t want density in their neighborhood” and “some of the developers and homebuilders that don’t want any more regulation.”

But without such changes, she sees a bleak future, one where “we are busing in workers from other counties, we have a greater divide between the haves and the have-nots, we’ll have more homeless people. We’ll have more renters in substandard conditions because that’s what landlords can get away with.

“We lose who we are,” she continues. “This is a community that a lot of people have felt comfortable to move into. That’s a great thing. But you have to look at what was here that made them want to be here. It was this vibrant community with all levels. We just don’t have that anymore. A lot of the young people growing up here will move and find their opportunities in other places because they just can’t live here.”

To avert that, she asserts that a major part of the solution will need to come from City Hall.

“This is government of the people, by the people, for the people. The public needs to insist that the government deal with this in a whole lot bigger way than they ever have.”

—

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by its readers. If you like our work, donate directly to us on Patreon. Questions? Comments? Email us.