Asheville’s political culture is lately turning to wealthy executives to craft the response the affordable housing crisis. Excluding the people most affected by the crisis while giving leadership to those who caused or profited from it is a bad idea.

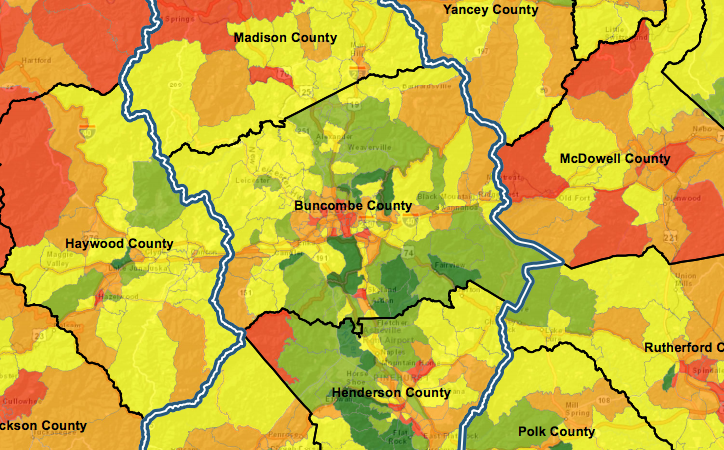

Above: a map of city areas by median income, from the 2014 Bowen report. Red areas have a median income under $30,000 a year, orange areas under $50,000.

Last week a number of local notables gathered at UNCA for a Leadership Asheville panel focusing on the city’s housing crisis. Some of these were no particular surprise — heads of affordable housing non-profits and the public housing authority — but the panel also included First Citizens’ Bank executive Pat Carver, Eddie Dewey of commercial real estate company Dewey Properties and Kit Cramer, the head of the Asheville Area Chamber of Commerce.

This continues a recent trend where such panels feature more and more such executives. Long the domain of activists, advocates and non-profits, as the crisis has worsened some of the business elite have declared that they can help step in and stem the tide on the affordable housing issue, with prominent leadership roles, of course.

Last week’s event was far from the first time this trend became apparent. The Asheville-Buncombe affordable housing summit last year (intended to “focus on solutions”) treated us to panels peppered with developers and banking executives, crowned by the sight of Biltmore Farms President Jack Cecil — a man whose family has lived in mansions for about half a millennia — presiding over an affordable housing panel. There Cecil declared that he was an optimist who sees “the glass half full.” Born with that kind of silver spoon, who wouldn’t be?

It’s not that some decent ideas don’t occasionally end up broached at such forums, whether held by local government or private organizations (full disclosure: I participated in a Leadership Asheville media panel last year), but their make-up sadly points to a major problem with how our city’s political culture thinks about and is trying to tackle the affordable housing crisis.

How that crisis is (or isn’t) addressed is key, because it’s really, really bad. Asheville’s notoriously poor wages have collided with skyrocketing housing costs to create a problem so dire it’s putting our fine city alongside major metropoli on some lists of the most unaffordable places in the entire country. A detailed 2014 report found that unless you make more than $75,000 a year, finding affordable housing to rent or own is increasingly nigh-impossible. City elected leaders have admitted, repeatedly, that their previous methods and programs can’t possibly hope to cope with the scale of the problem (that’s one of the reasons a $25 million bond on the issue suddenly became politically feasible this year). It’s certainly a complicated topic, and recent years have seen debates about how accurately the city measured affordability and if — as some housing advocates asserted — there were major steps it could have taken and didn’t.

But this recent trend is bad for a number of reasons that aren’t that complicated at all. Let’s start with the obvious: the fact that these panels have excluded renters struggling with the crisis entirely, even though just over half the city rents rather than owns. That’s probably the easiest part of this whole approach to fix. Going forward, it’s absolutely necessary to have more renter/worker representation at panels, summits and crafting any future policy, including the voices of some of the many public housing residents trying to ensure that their rights are protected.

The deeper problem is the exclusion, even if unintentional, of the voices of those most affected by the crisis in favor of those who profited handsomely from it. These magnates are on the panels because the city’s current political culture sees them as “stakeholders” essential to solving the growing problem.

In theory, and once in awhile in practice, the “stakeholder” method can work (if you need to decipher this and other jargon that pops up in these kind of discussions we have a handy guide). It’s supposed to mean those with some direct involvement in an issue that the city calls on to solve a problem or craft a policy. That’s all well and good if “stakeholders” are residents of a neighborhood affected by a particular policy or representatives of a grassroots organization with direct knowledge about a given issue.

However, too often “include stakeholders” and “focus on solutions” actually means “let’s make sure any proposed policies don’t upset people with power and money, even if that’s what’s required to actually solve the problem.” It can act as a way of avoiding the obvious, turning a blind eye to how the current crises came to be and a deterrent against real civic engagement by anyone not already within the elite.

So if we’re talking stakeholders, let’s talk about stakes. Specifically, what kind of stakes Asheville’s elite could put up if they truly felt housing were a crisis.

According to the Chamber’s 2014 filings, Cramer makes $264,398 a year (equal to the starting salaries of almost seven public school teachers, for context) as the head of the chamber. She’s not alone in getting a generous salary from that organization. Stephanie Brown, who heads up the Convention Visitors Bureau, brings in a solid $211,863 a year. If they could survive on just $100,000, they have the resources to make a considerable contribution to affordable housing every year.

Sure, that’s crude math (taxes, withholdings, etc.), but the larger point is that if the executives in the room for these affordable housing panels and summits seriously wanted to make a dent in the affordable housing crisis, they have personal resources to do so, while leaving them funds still far, far above what the vast majority of the city’s people manage on.

More importantly, Cramer’s cash comes from an organization whose members have profited considerably off of low wages, skyrocketing housing costs and building for tourists rather than residents. The same applies to Cecil and Biltmore’s various companies. Notably, both the chamber’s leaders and Cecil played a role in spiking even modest attempts to direct some share of the hotel tax to the public coffers in favor of continuing to use the funds to market the area to tourists, something Cecil claimed was necessary because — in its infinite wisdom — the hotel industry drastically overbuilt.

The myth at the heart of this is that Asheville’s housing crisis is some sort of natural disaster, like flooding or a tornado, emerged to ravage the people due to factors beyond anyone’s control. Certainly, this line of thinking goes, it’s nothing that’s anyone’s fault or requires any real changes to the way the city works.

While Asheville’s CEOs and property barons certainly didn’t wake up and go “let’s cause a housing crisis so bad it makes national lists,” the fact is that everything that led to this situation made them a lot of money for a long, long time.

That approach had consequences, of course: a city with higher all-around wages, better job prospects and more affordable housing would have made everyone more money, including them.

But most parts of business culture are set up for one purpose only: to accrue as many resources for the business as possible. That makes the same culture — whatever its pretensions — the epitome of penny-wise, pound-foolish, prone to the kind of runaway greed that caused the housing crisis (and the hotel bubble) in the first place and historically terrible at the kind of long-term, wider-view thinking necessary to solve it. In short, it breeds a mentality uniquely awful at solving public problems to the benefit of, well, the public.

Bluntly, it’s also not really a crisis for them and many don’t want to give up the power dynamic that comes with a desperate labor pool, weak worker and housing protections and a landlord’s market.

But now that the housing crisis is so severe that it’s even hurting business’ ability to recruit and retain, they’re suddenly concerned. Great. Better late than never, I suppose, but you’ll forgive that I’m not really convinced of their sincerity, considering that the problems at the heart of the crisis made them so much for so long.

I don’t mean to just single out Cramer either; the problem goes far deeper than any one person or organization. The chamber as an institution profited off the dire situation of Asheville’s workers and an overheating housing market long before she took office — and they’re not alone.

Indeed, the executive salaries of other major employers offer even riper ground for resources to direct at the crisis currently threatening thousands with eviction, homelessness or exile from the city they’ve helped build.

Most companies’ executive pay aren’t public knowledge, including privately-held ones like the Biltmore behemoths. Despite the name, Biltmore Farms’ business is hotels, housing for the wealthy and commercial real estate, the sort of thing that’s made bank during the current crisis. So I’d wager (a local beer for anyone who can prove me otherwise) that the pay of Cecil and other bigwigs in both Biltmore Farms and the larger, tourism-fueled Biltmore Company makes Cramer’s salary look positively modest.

Those of Ingles Markets executives certainly do. Because the local grocery giant sells shares, it has to file documentation with the SEC, including revealing the compensation of its top executives. In 2015 CEO Robert Ingle, II brought in just over a solid million (about 27 school teacher salaries) from the company he inherited, as did President James Lanning. The company’s CFO raked in $434,615 and the head of its dairy wing $257,281.

Another major employer whose top salaries are known is the biggest of them all: Mission Hospitals. They recently made headlines for adopting a living wage ($11 an hour with benefits in this case) for about 200 of of the hospital chain’s lowest-paid workers, mostly cafeteria and cleaning staff.

According to their 2014 filings, Mission CEO Ron Paulus — the head of an ostensible non-profit, mind you — brought in $1.3 million (that’s 33 starting teachers’ salaries). Taylor Foss, the VP that publicly touted the recent shift to a living wage, made $517,084 that year. It doesn’t stop there. Mission’s CFO received $735,439, its COO $786,088, its general counsel $457,107 and so on. All told, all of Mission’s 22 paid executives made more than $200,000 a year, 15 made more than double that.

So let’s see some sincere, shared sacrifice. The workers in the businesses that form the chamber have scraped by to make them money for years. Mission’s obviously doing pretty well. Ingles is expanding rapidly and Biltmore’s making money hand over fist. I’m sure Cramer, Cecil, Paulus and other CEOs could pare their salaries down to a mere annual $100,000 — just for a few years until rental rates stabilize and the crisis eases — and donate the remainder to building and supporting affordable housing.

They can call it the “$100K challenge” if they like, a lovely way to put all those budgeting skills and entrepreneurial ingenuity to work. Despite my abundant skepticism I will happily abide the inevitable flood of self-congratulatory press releases they could issue because in the meantime whatever housing program received their excess cash — a non-profit laboring in the trenches, the city’s housing trust fund, pick one — would have a great deal more resources at its disposal. If those resources were then spent on plans led and developed by those directly affected by the crisis, we might get somewhere.

If just the executives whose salaries we know — for the chamber, Ingles and Mission — all donated their annual pay above $100,000 to affordable housing efforts, that would be a bit over $11.4 million a year (or about 293 starting teacher’s salaries, if you’re keeping score). For comparison that’s about 23 times the city of Asheville’s entire annual affordable housing trust fund contribution and over twice the $5 million the proposed bond referendum might put into the same fund as an extraordinary, one-time measure.

Keep in mind, that’s only the executives from two major employers and two chamber chiefs and it still leaves all of them with a generous amount of money per year. Again, the math is crude, but even pared down by a few million that’s a lot of funds to seriously fight the problem, especially considering that the organizations working on the affordable housing crisis here could leverage that substantially for additional financing and resources.

I’m sure the executives of other major employers around town could make considerable donations of their own — hell, throw in the heads of the two Biltmore companies and who knows how far we could go — meaning this is only a fraction of the amount that our local executives could direct at the affordable housing crisis. If they chose to.

Or they could go farther and get even more serious. The chamber could require that any business receiving the benefits and connections membership there provides pay a living wage (because the gap between pay and housing costs is at the heart of the housing crisis). Some of them do already, so they could even sell it as “let’s not undercut each other and ensure more money goes back into the local economy.” Biltmore, Ingles and numerous other companies could sit down with Fight for 15 leaders and go “you know what, you’re right, wages are far too low and we value our workers. Let’s show some leadership, raise our starting wages to $15, put some real labor protections in place and go from there. We’ll all end up better off.”

But that won’t happen, because the view of the world at work here won’t allow it.

This is after all the kind of mentality that was for many years perfectly fine with executives making massive salaries — including while heading up a non-profit — while janitors and cashiers scraped by. This is the view that saw no crisis in crud wages shoving Asheville’s workers farther and farther out of the city they make possible until the greed metastasized to such ridiculous levels that it started to hurt even their prospects. This is the belief that there is nothing wrong with using a living wage as a marketing perk before dropping it after a corporate expansion.

Asheville’s housing crisis is a human problem, one that’s already devastated lives and promises to devastate far more in the coming years. It is an injustice made by people and, every day, upheld by them too, consciously or otherwise.

Now they want to be “stakeholders” in affordable housing solutions? Grand. Put up a stake. They truly believe this is a crisis? Act like it.

But until they are ready to both admit wrong and make a serious effort to address it, we shouldn’t just take their words with a shaker full of salt, we should ignore them entirely. They and their predecessors built this crisis. Maybe, just maybe, they’re not the people to look to for solutions.

—

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by its readers. If you like what we do, donate directly to us on Patreon or make a one-time gift to support our work. Questions? Comments? Email us.