The response to recent protests by APD leaders and the city attorney’s office is marked by petty retaliation, contempt for civil liberties and repeatedly shifting explanations, giving locals of all political stripes cause for major concern.

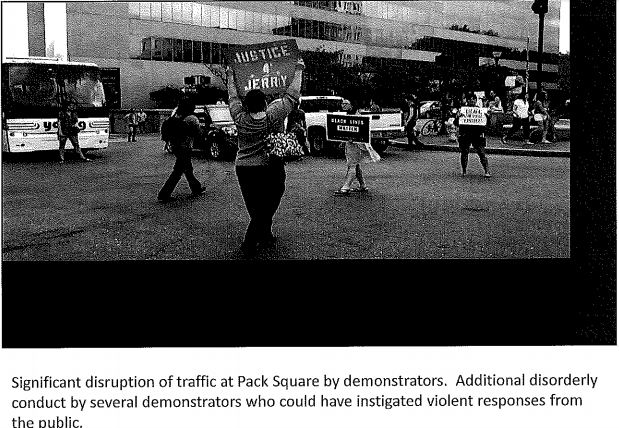

Above: a slide in an Aug. 3 APD presentation about its response to late July protests. The city delivered the grainy black-and-white scan of the presentation in response to the Blade’s record request.

On July 21 protesters started to gather outside the Chamber of Commerce.

They had come there in response to the July 2 killing of Jerry Williams by APD Sgt. Tyler Radford, something that’s rocked the city to its core, especially around issues of policing, force and segregation. Police asserted that Williams was “displaying” a gun and had participated in an earlier shooting, but only Radford was on the scene when the shots were fired and eyewitness accounts differed, ranging from uncertainty about what happened to asserting Williams was unarmed and trying to surrender. There are multiple conflicting stories about the events that evening, and the shooting is currently under investigation by the State Bureau of Investigation.

The aftermath tapped into skepticism about the APD’s conduct springing from long-running issues and controversies, especially from the city’s African-American residents. In its aftermath, protesters from an array of groups demanded reforms of differing varieties through vigils, protests or promises to craft new policies.

The particular protest that morning was organized by Showing Up for Racial Justice, a largely white ally group of Black Lives Matter. Protesters unfurled “Justice 4 Jerry” and “Black Asheville Matters” banners. They were calling for the firing and indictment of Radford and an apology for Williams’ killing from the APD, along with a series of reforms to police and local government, ranging from bias training to directing more resources to marginalized communities.

Just before the march began Amy Cantrell, a local minister and head of BeLoved House, told protesters that if directed to move onto the sidewalk, they would do so.

Despite Cantrell’s caution, no order came. As the protesters proceeded down Haywood a police car near the St. Lawrence Basilica turned on its lights and blocked traffic coming from Flint Street so the march could proceed. Other officers, near the intersection with Walnut Street, observed as the march proceeded and protesters handed out fliers, including a summary of the State of Black Asheville reports.

So far the response was in keeping with how the APD has generally handled public protest in the city’s core. Despite occasional controversies and criticisms over the past decade — especially during the early days of Occupy — the Asheville police have generally taken a fairly light hand. When several Black Lives Matter protests took place in the heart of downtown in late 2014, for example, police presence was generally minimal. When marchers at one such demonstration that year moved into the intersection of Biltmore and Patton, temporarily blocking traffic, police moved in to direct cars away, but did not arrest the protesters or order them to disperse.

On July 21, the protesters would go on to occupy the APD lobby, where seven of them would eventually be arrested, about 30 hours later, as part of a sit-in. That evening, some locals showing up to protest in support of the demonstrators then ensconced in the APD lobby would block the intersection of Biltmore Avenue and run into confrontations with some drivers.

But things would be different this time on the APD’s end, specifically as they took a harsher approach to protest than Ashevillians have seen in many years. This is the first major time Chief Tammy Hooper, appointed last year as the city’s top police official, has responded to public protest, so those differences are important to delve into. They’re very possibly the shape of things to come.

So what follows is what’s known about the disputed parts of the protests and the aftermath — including the controversial after-the-fact arrests of protesters based on social media videos and postings. Both the sit-in protesters and those cited as part of the demonstrations and marches have their first court date today.

Then, I feel I have an obligation to go further, which is why this isn’t going to be a typical follow-up piece; its latter section, detailing the considerable civil liberties problems raised by the response to the protests, is an opinion column.

Whether one sides with the protesters entirely is not the point. You may not personally agree with all of their tactics or actions, or have a different idea about the steps necessary to reform policing in our city. Those are debates the people of Asheville can and should have.

But what I believe should alarm everyone — citizens, activists and journalists — is the response by the APD’s leadership and the city attorney’s office to acts of protest not particularly different from those that have happened in Asheville many times before: except that they specifically criticized the city government and police department’s actions.

That response was marked throughout by petty retaliation, contradictory explanations, contempt for a free press, disregard for civil liberties, ham-handed intimidation and what is at best incredibly sloppy investigation and at worst outright deception of the public. In a time where trust is at an all-time low, there’s no approach more damaging to our city’s future.

Change of tactics

The protesters’ occupation of the lobby lasted about 30 hours until the sitting protesters (and one journalist) were arrested. The demonstrations were part of an array across the country protesting police violence, with SURJ and other groups focusing on local killings or misconduct as well as national issues. Those ranged from brief marches and vigils to protesters locking themselves to the doors of a police station.

In Asheville, the tactics were different; no locks, for example, and no attempt to shut down access to the police station. The protesters filled the lobby and placed banners over the main doors into the APD station. They also removed them several times to let people in or out. They sang, chanted and shouted slogans about their demands and views. At no time among the protesters in the police station did I witness any threats, physical altercations or attempts to block people from entering or exiting the building. Even a sometimes tense verbal exchange with FOP President Rondell Lance, who showed up at the protest and has repeatedly asserted that Williams’ killing was justified, didn’t escalate beyond simple disagreement.

The length of time was a bit of a surprise, as the tactic of protesters occupying a government office and holding a sit-in is far from new. The We Do campaign for equal marriage rights, masterminded by the Campaign for Southern Equality and endorsed by many local elected officials, repeatedly filled the Register of Deeds’ office with protesters over the years. After repeated couples were turned down, Register of Deeds Drew Reisinger would receive their demands, assert that he agreed with their goals but could not issue the licenses due to state law. Then some of those demonstrators would conduct a sit-in. Reisinger or a sheriff’s deputy would, after some time had past, warn them that they were risking arrest if they remained. After repeated cautions, they would be arrested and given a minor trespassing charge. If the APD’s response to the lobby demonstration had followed suit, it probably would have been concluded in a few hours.

Instead, the building shut down, APD staff closed the window they usually conduct business through and started meeting people around a side door. When locals came in to get a car out of impound or find a document, police staff told them through the intercom that the building had been shut down for safety concerns (protesters at several points also directed locals as to where they could meet police for those services). Repeatedly, the protesters asked to speak to Hooper or an APD representative to present their demands. None came. At various points, officers and police staff told the protesters that they were trying to work out who would come speak to them.

Around 6 p.m. some locals came out in support of the protests (the time had become a regular event for those protesting Williams’ killing to gather near the station).

In this case, part of that group blocked traffic at the intersection of Biltmore and Patton while others held signs on the sidewalks. This tactic isn’t unheard either. Protesters have at multiple points over the years done the same, including during environmental protests, May Day rallies and Occupy demonstrations. Generally, the APD has not responded with arrests, though it’s not uncommon for them to direct traffic away from the site or observe from a distance. Those exceptions usually involved incidents where police repeatedly directed protesters to disperse or move onto the sidewalk first.

During the July 21 evening protest, I was inside the police station lobby and did not directly witness it. Later, APD representatives said that they declined to give an order to disperse (or any significant police presence) due to not wanting to escalate the protests, asserting that there was a possibility of violence and that their manpower was involved in responding to the protest at the APD lobby. Department leaders have also repeatedly and incorrectly conflated the very different evening and morning protests as one demonstration.

During the morning march, I observed minor delays caused by the protesters as they marched, but no confrontations with drivers or passer-by.

In the evening demonstration, some protesters tried to block cars that attempted to push through. On a brief video of the protests (the one the police would later highlight), several get in front of a car to stop it moving through their group. The video also appears to show the tail end of a confrontation with the driver of a vehicle that moved through the group of protesters, with one demonstrator repeatedly shouting at the driver “there are people there!” while before banging on the side of their truck. As they drive away (after shouting back inaudibly) the protester shouts “fuck you!”

Other than the time I was asleep that night, and some brief breaks to get food, I observed the initial march and subsequent sit-in from beginning to end.

Just after 2 p.m. the next day, July 22 the arrests came, after the APD had directed the protesters to leave. At first it looked like the APD was following their usual approach (folding up the “Black Asheville Matters” banner and handing it back to the protesters, for example). But some key things would be very different this time. For one thing, police ordered observers not directly involved in the sit-in out of the area and had multiple police officers block off the windows, making observing the arrests directly difficult.

While it’s not uncommon to have police clear a distance for an arrest to take place at a protest, and ask journalists and observers to step back, I’ve seen them do so in spaces more cramped than the portion of the APD lobby the protesters were still occupying (like, say, the Register of Deeds’ office). The differences in policing this particular protest didn’t stop there.

Find and report

Civil disobedience to raise awareness of a cause has a long tradition in America, and in Asheville. Cantrell and the other six protesters went into the situation expecting to be arrested as an act of political protest.

One person that didn’t, however, was Dan Hesse, a reporter for the Mountain Xpress, the aforementioned journalist. I witnessed Hesse there and at no time observed him blocking police officers or doing anything different from what a journalist covering a protest would normally do, observing the actions of all parties, taking photos and interviewing some of the people involved.

If protests are nothing unusual in Asheville, neither is the presence of journalists at them, whether it’s marches filling the street, occupations (including of public property) or sit-ins.

In this case however, despite no clear command for the media (as opposed to protesters) to leave, at least none that Hesse heard (he’s deaf in one ear), the APD arrested him, despite the fact he repeatedly identified himself as press. This isn’t just unusual, it’s unheard of, as Hesse, a local reporter for over a decade, detailed in a column about his experience.

I asked the APD about Hesse’s arrest and received the following reply:

Hesse was present for at least two of the discussions between the demonstrators and police liaison, Captain Stony Gonce, in which participants were asked to voluntary [sic] come into compliance with laws that they were in direct violation of. In addition, Mr. Hesse was also present when demonstrators were provided with a final notification to voluntarily leave the Municipal Building and that those who chose not to voluntarily leave would be arrested. At the time of the final notification, approximately 17 individuals were present – including media representatives from other agencies – and approximately half of those individuals voluntarily left the building. There is no statutory exemption for media representatives to be in violation of the law and not be charged.

While Hesse and the protesters were being arrested, Hooper, who hadn’t spoken to the protesters during the entire occupation, found time to give an interview to WLOS.

She also confronted Cantrell within the police station, while the protester was still handcuffed and in custody.

The account released by SURJ after the arrests describes the meeting this way:

Cantrell was then separated and taken to an impromptu meeting inside the building with police Chief Tammy Hooper. Present were Hooper, a sergeant and three other officers. Hooper expressed extreme frustration that protestors had created a spectacle by occupying the lobby of the APD. She demanded a meeting with Cantrell, who could not accommodate the request, being in handcuffs, without a calendar, and separated from the rest of her group who would also want to attend any meeting.

When asked, APD spokesperson Christina Hallingse confirmed that this meeting took place, describing it as follows:

Chief Hooper did meet with Mrs. Cantrell, as she was the designated spokesperson for the group. During this meeting Chief Hooper offered to schedule a follow-up meeting, however Mrs. Cantrell was unable to do so at the time. Chief Hooper offered to follow-up with her regarding the scheduling of a meeting and neither Chief Hooper, nor the Asheville Police Department, have heard from Mrs. Cantrell since July 22nd.

By the next Monday, when Asheville City Council’s Public Safety Committee met on the upper floor of the police station, the building remained on lockdown, with an officer controlling access to the front door.

At that meeting, after activist Sabrha n’haRaven said the lockdown was unnecessary and constituted a barrier to many in the community attending, asking “why are their guards and locked doors today?”

Asheville City Council member Cecil Bothwell, the committee’s chair, wondered if it was because the police worried about another occupation by protesters. Hooper asserted that was correct “we’ve enhanced security to ensure our police stay secure and we stay safe” but that they wouldn’t turn anyone away. She added that the lockdown would last for the immediate future, as “we don’t actually have the resources for it to be a permanent state, we’d have to do a whole lot of additional security.”

The Council member added that based on his experience talking to protesters and seeing news reports, he believed the APD responded to the sit-in professionally.

The police chief made no mention about follow-up arrests, which would start in the days afterwards. Searching videos and social media posts, the APD would eventually cite 21 people for impeding traffic and while the department would not tell media how many personnel or resources they used in the effort, court documents reveal that at least five officers were involved.

This is also incredibly unusual. The APD hasn’t done after-the-fact arrests for involvement in a protest, including blocking traffic, since the early days of Occupy Asheville in 2011. Those arrests, including one for handing out a pamphlet, an activity protected by the First Amendment, resulted in widespread public backlash. In the wake of that, police officials backed off the approach and generally took a more careful attitude to protest, with a lighter presence and a general practice of giving repeated warnings before an arrest. In 2013 Council passed a civil liberties resolution emphasizing protections on the right to protest.

City ordinance, which has multiple rules on picketing, prescribes the following for when a protest blocks traffic:

(1)

Whenever the free passage of any street or other public area in the city shall be obstructed by picketers, persons picketing shall disperse or move along when directed to do so by a police officer of the city.

(2)

Whenever the free passage of any street or other public area in the city shall be obstructed by a crowd, the persons composing such crowd shall disperse or move along when directed to do so by a police officer of the city.

(3)

Nothing in this section shall prohibit any person from reconvening after dispersing so long as free passage of any street or other public area is not obstructed.In neither the morning or evening protest was there an order to disperse.

Technically, however, the protesters that participated in the July 21 morning and evening marches are charged under a state law that reads as follows:

§ 20-174.1. Standing, sitting or lying upon highways or streets prohibited.

(a) No person shall willfully stand, sit, or lie upon the highway or street in such a

manner as to impede the regular flow of traffic.

(b) Violation of this section is a Class 2 misdemeanor.

On Aug. 3, the city’s Citizens Police Advisory Committee heard a presentation from Deputy chief Jim Baumstark, like Hooper recently come to Asheville from a Greater Alexandria law enforcement agency, who laid out the department’s justification for the arrests.

Baumstark referred to “the demonstration” and showed the video of the evening march, claiming it had taken place just before the marchers had proceeded to occupy the police department lobby that morning (he also showed photos of the morning march, again claiming it was the same demonstration as the evening one).

“You can see we have people in the street now pushing on cars, stopping traffic,” he told CPAC and the public. “You can see we have people coming up and beating on the car, beating on the windows. I apologize for the quality. From Pack Square it continued down, they took over the entire intersection yet again and then you had some of the individuals come in and started occupying the lobby of the police station.”

He claimed that the APD knew very little about the morning march when it started, but had followed along “to try to get it to move a little faster and to help with the confusion” but that after it arrived at the Pack Square intersection the demonstrators took over the area and protesters “started banging on cars, arguing with motorists in the intersection.”

This did not occur at the morning march, which I observed along its entire course. Rather than taking over the intersection as Baumstark describes, the morning demonstrators only paused there briefly before proceeding on: based on the times of photos taken during the march, it took just 14 minutes for the marchers to travel from Pritchard Park, through Pack Square and to the police station.

Baumstark said that any citing of protesters at the scene would have escalated the situation and asserted the protest was not peaceful. He also stated again, incorrectly, that the confrontations in the video of the evening protests were done by the morning marchers, something which several observers and activists would point out in comments at the same meeting.

His power point presentation went further, asserting that “the APD and the City wanted to avoid crowd escalation into potential dangerous behavior and destruction of property.”

At the meeting, he added that the department had received multiple complaints and that locals had helped them identify protesters who they had then gone on to issue citations to, after consulting with the city and district attorneys.

“There is a correct way to do a march and protest, this is Asheville, every day there’s a protest, they do it peacefully and get their point across,” Baumstark said.

At the same meeting, DeLores Venable, speaking for the Asheville chapter of Black Lives Matter, proposed a series of reforms, including direct community oversight, more body cameras, more consequences for misconduct and better training.

She also noted that despite the illegality of the sit-in, “the tactic did work” in drawing attention to an important issue. Venable also criticized the APD’s response in charging protesters after the fact.

“If we want to have better community and policing tactics going to people’s houses unannounced to serve a citation is not a great way to do that. Picking images off of social media? Not a great way to do that. That is turning our city once again into a police state. This is not viewed very well across the city of Asheville, especially in black and brown communities.”

When members of the public at the meeting later asked the city attorney’s office to clarify its legal stance on the citations, assistant city attorney John Maddux declined, though staff said they might do so at a later date. Other activists noted that the APD hadn’t initially shut down threatening comments on its July 27 post about the protests, including people wanting to run over protesters and kill them.

The day before that meeting I asked the APD why, after five years, it had suddenly changed its tactics with regards to the approach to protests and after-the-fact arrests for blocking traffic, this was the reply:

The demonstrators did not obtain a lawful permit, therefore the City of Asheville was unable to provide advanced notice of the route or possible traffic disruption in the downtown area. As a result it caused delays for many citizens traveling through, and working in, the downtown area. The Asheville Police Department strongly supports and respects the constitutional right of individuals to practice their freedom of speech and protest, and we have demonstrated that respect throughout this process. Individuals are not entitled to conduct themselves in a manner that is unlawful and infringes on the rights of others.

This approach didn’t go entirely uncriticized, either. Asheville City Council members Brian Haynes, Keith Young and Bothwell (the architect of the 2013 civil liberties resolution) issued the following statement after news of the citations emerged:

From our viewpoint we don’t see how this action can be fruitful moving community relations forward. We understand the need to uphold the law. However, we don’t think anyone would be too thrilled about receiving a citation days after the alleged incident.

The action may be lawful to cite folks after the matter, but it is our opinion it’s counterproductive for long-term conversations. The time for enforcement is in the moment. However, a great deal of deference and compassion was rendered to the actions of protesters. We totally understand the need to enforce the law, as it is the duty of sworn officers.

Anyone exercising their first amendment rights should do so with the knowledge moving forward that certain actions are not inconsequential. Any adverse action, that does not comply with NC General Statutes are subject to enforcement.

As we continue to step out. We constantly ask the community in good faith, to lean into a better commitment with regards to relationship building, especially with our police. This current action leaves us three perplexed and scratching our heads. We support the right to peaceably assemble and we support our police but this is definitely in our opinion a faux pas.

However, Bothwell also declared his confidence in Hooper in his own statement to the Blade Aug. 10, writing that “the nation is confronting painful issues around racism, bad police conduct, and failure of accountability. In my view APD Chief Tammy Hooper is handling a very fraught situation with professionalism and sensitivity. I may not agree with every decision, but I don’t think we could hope for better leadership during difficult times.”

Further wrinkles developed from there. When police can’t find someone to issue a citation, it eventually becomes a warrant for arrest and, as the days wore on, several protesters found out that there were warrants out for them. I asked the APD to clarify when these citations for a minor traffic violation, which can simply be delivered to a person, became warrants for arrest, meaning the protesters could be detained and processed through the Buncombe County jail anytime the APD found them. They declined to answer directly and instead directed me to look at court documents.

Those documents show two main waves of citations, on July 27 and July 29. Many of the protesters who weren’t immediately handed a citation had warrants issued for their arrest the same day, July 29, though in at least one case a protester wasn’t issued a warrant until Aug. 2 (due to differences in spelling and other details in the APD’s list of those charged, not every warrant could be located by the clerk of court’s staff).

One of those who ended up with a July 29 warrant for their arrest was Calvin Allen, a longtime advocate and member of the city’s transit committee. Allen briefly gathered with protesters at the chamber before they commenced marching into downtown. He had also spoken before top police officials, city staff and the public at the Aug. 3 CPAC meeting — unaware that there was a warrant out for his arrest at the time — asking for more clarification about the details of Williams’ shooting.

Allen has lived at the same address for years, an address the city had on file due to his committee member application. He was not delivered the citation and was not made aware of the warrant, he claims, until informed by a lawyer in mid-August, nearly a week after he’d spoken to the police board. He went down to the Buncombe County Magistrate’s Office (located in the jail) on Aug. 11 to receive the citation and ended up spending about four hours in custody before he was released.

Once that incident became public, it also resulted in criticism from Bothwell, who wrote:

It seems wrong to me that a person who learns that police failed to deliver a citation and who goes to the police station or courthouse wouldn’t simply be given the citation. I understand the legal argument that once a warrant is issued an arrest is required, but it makes no sense to me given the originating event. Why not hand the person the citation? What good was accomplished by the wasted time and expense for all concerned?

The problems

From this, I have to conclude that from start to finish there were major problems with the city’s response every step of the way, and that given the basic problems raised, these must be commented on. Let’s start with the reaction to the sit-in.

If the protesters were actually a big enough problem that they needed to be cleared out, that they caused security risks or seriously impeded services, the APD could have sent officers in and done so. It could have sent Hooper or another top APD officer (they have two deputy chiefs and four captains) to briefly talk with the protesters before arresting those involved in the sit-in, as it eventually did the following day. It’s not like that approach would have been a new one to protests in Asheville, including for ones that used almost the exact same tactics as this sit-in.

The decision to shut down the service window was made by the APD. Agree with their tactics or not, I never witnessed the protesters shut someone out from trying to access the services usually provided at the building. While I witnessed plenty of noise, pleas, chanting and criticism, I also definitely never saw the protesters do anything that could be interpreted as a threat to anyone’s safety.

So after hearing APD officials and staff repeatedly cite supposed safety and security problems caused by the protesters’ presence, I asked them to specify what those problems were, and the costs — the ones Hooper had mentioned — that were associated with the lockdown.

When I received a reply on Aug. 5, the APD dropped the safety concerns entirely and Hallingse claimed , contra Hooper’s statement on July 25, that the lockdown was only to “to ensure that we could provide unobstructed access to the public for both police and fire services.”

The same happened with the supposedly high costs of keeping the building on lockdown, the ones Hooper also mentioned on July 25 as constraining the time the department could keep the building in that state. Despite the police chief telling the Public Safety Committee that they didn’t know when the lockdown would end and that it would entail considerable extra costs, Hallingse later wrote that it only lasted one day longer, until July 26, and there were in fact no extra costs at all for the heightened security manning the front door, “as this officer was working his regular on-duty shift.”

Either the APD’s shifting its explanations just to try and paint the protesters in as bad a light as possible, or there are serious communication issues within the department over basic details of an important incident. Neither is comforting.

Then there’s the matter of arresting a journalist. Hesse’s account of his arrest is revealing, from how it differs with the approach to protests he and plenty of other local journalists have observed to police’s use of technical jargon to avoid doing something obvious like loosening a journalist’s restraints.

Nor is Hesse the only member of the press facing charges. Ponkcho Bermejo was photographing and recording the event for BeLoved House’s Homeless Media Project (several members of the group were involved in the protest), and even had a lanyard on identifying him as a media observer. I talked to Bermejo briefly and saw him at multiple points during the march to the station. His actions were nothing that countless journalists and photographers — myself included — haven’t done over the years while covering protests in a variety of situations. Neither were Hesse’s.

Fortunately, in Hesse’s case the District Attorney’s office dropped his charges, citing the necessary role of the press. I hope they will do the same for Bermejo.

But the fact that they were charged or arrested in the first place is already a major problem. The justification given by the APD and the city attorney’s office, that “there is no statutory exemption for media representatives to be in violation of the law and not be charged,” should worry every member of the press in Asheville. Taken to its logical conclusion — and given the city attorney’s historically ludicrously broad reading of police powers — it can be used to arrest practically any journalist covering a protest or police action. Indeed, that intimidation might be the point.

Protesters fill a road and you step in front of them to get a photograph? Arrest. Protesters occupy public or corporate property and you go to interview them? Arrest. Even if the charges are later dropped, it provides an easy way to clear out observers of the police’s actions and hassle the press. It opens the door‚ if one’s intent on reading a law broadly enough, to use police discretion to punish media officials might feel aren’t sufficiently sympathetic.

However, while incredibly disturbing, this shouldn’t come as a surprise: this approach is sanctioned by the city’s legal department. In a column back in April I pointed out that under City Attorney Robin Currin the office had repeatedly taken stances contrary to basic transparency and civil liberties, even to the point of embroiling the city in a lawsuit over footage of — ironically enough — surveillance of peaceful protesters.

If anything, this case illustrates the need for press and other observers to be around protests, especially during arrests and other police responses.

Hooper’s confrontation with Cantrell just after her arrest is also deeply troubling. It’s one thing for the police to arrest someone engaged in an act of civil disobedience (after fair warning and without the use of violence). It’s one thing for a police official to disagree with a group of protesters or their specific demands. It’s quite another for a police chief to insist on speaking with a public critic of a department’s actions only flanked by other officers, after the person is physically restrained and in their custody.

That’s incredibly unprofessional, to say the least. It is, obviously, score-settling and direct intimidation in retaliation for an act of protest directed at the APD.

Then there’s Allen’s arrest, and the implied threat to protesters there. Allen’s well-known to city officials because for several years he’s helped advise them on transit policy and advocated on a number of concerns, including policing in public housing, many times. The idea, especially after he even went into the police station to address the Aug. 3 meeting, that for two weeks he couldn’t be located to deliver a basic citation is ludicrous.

The logical extension of this approach is again, plain intimidation, the assertion that police can cite protesters after the fact for participating in a demonstration, turn those citations into arrest warrants the same day, not tell the protesters and then arrest them, well, whenever. Protest in Asheville starts to look very different if everyone who steps into the street at any point during a demonstration is facing the prospect of being randomly arrested and hauled to jail weeks later based on an officer’s brief look at social media. Furthering that fear, like declaring that media might be arrested for covering protests, might well be the point.

It raises even more problems alongside the APD’s repeated conflation of two separate marches, which is one of the most disturbing parts of this whole thing. That assertion immediately seemed dubious to me, as the video Baumstark played at the Aug. 3 police board meeting noticeably had different people, different light and different circumstances from those I observed on the morning march. Here’s a picture of the protesters marching down Patton Avenue the morning of July 21 toward the police station.

While the video from the evening protest, taken at the other end of the same street, clearly shows the sun visible in the West (this is particularly apparent about 10 seconds into the video).

While we can debate the protesters’ impact, I think it’s beyond dispute that they don’t have the power to change the position of the earth relative to the sun.

On Aug. 2, the day before Baumstark’s presentation I pointed out that the photo the APD posted on its Facebook account on July 27, announcing that it would cite protesters, wasn’t from the march on the morning of July 21. I asked why it was used and if they were aware of this.

I received the following reply:

The Asheville Police Department utilized publically [sic] available information in order to assist in the identification of those that participated in the march. This information came from the organization’s Facebook page, YouTube and media footage. The photograph was derived from those sources.

As of this morning, the photograph is still up on the APD’s Facebook page and they’re still associating it with the morning march.

I wasn’t the only one to notify the APD that they were conflating the two protests in their public media statements. Longtime activist Clare Hanrahan, who acted a legal observer for the protesters during the march and sit-in, and observed both the evening and morning protests, pointed this out at the Aug. 3 meeting, as did activist Vicki Meath. So far, there has been to my knowledge no clarification from the APD that there were two separate marches, and that the confrontation depicted in the video took place at the evening protest.

In the best possible scenario, the police missing this basic fact in the course of their investigation makes it incredibly sloppy: establishing when something happened and the basic chain of events before and after it is literally Investigation 101. If neglecting this core part of their duties is what happened, that is a cause for deep concern about the level of expertise and training present in this investigation, as well as an unwillingness to adapt when new information is directly pointed out to them, as it was over a month ago by both media and activists.

At worst, some within the APD were intentionally deceiving the public to associate the relatively peaceful morning march that began the protest with the confrontation that happened much later that day. Furthermore, they did so repeatedly, even when directly asked to clarify the situation and even after informed by other observers that they were conflating two very different events.

If that’s the case, the city of Asheville needs to figure out who was responsible for this particular deception and start firing people. If they lied about this, they’ll lie about far more important things in the future. With tensions this high, our city can’t afford that.

The APD handled multiple protests that used very similar techniques over half a decade without resorting to after-the-fact charges (or arresting journalists, for that matter). If either July 21 protest was actually causing a great enough disruption that it needed to be cleared, they could have done so with relative ease. As noted earlier, the organizers of the morning march specifically directed protesters in advance to move to the sidewalk if ordered, so all it would have taken in that case were words. I have seen local police repeatedly deal with far more difficult situations than those posed by the protesters, including at the evening march, without such heavy-handed tactics as going to one’s home and reprimanding them for a protest that happened a week earlier.

The “it’s the law” explanation falls apart too in the face of the APD’s leaders not opting to enforce this law this way until the moment a protest specifically criticized them and got considerable media attention after a controversial shooting. If the APD’s new direction is so insistent upon strict enforcement of traffic laws, there are intoxicated tourists aplenty to be found many nights in downtown, temporarily blocking traffic, getting into confrontations with drivers and even banging on vehicles. Plenty of them no doubt post about their drunken antics on social media. I won’t hold my breath for the wave of arrests.

My job requires me to do my best to understand complicated situations and present the relevant facts to the public as best I can. When I do offer an opinion (in an editorial, for example), it requires me to clearly label it as such.

It does not require me to treat fiction as fact, or abide the inability of city officials and departments to clearly answer basic questions about their conduct.

This is all the more damaging because this all comes at a time when trust in the city’s institutions, including the APD, is the worst I have ever seen in more than a decade covering local government.

Indeed, signs of problems with Hooper’s tactics and approach here reach outside the protests themselves. In the aftermath of Williams’ shooting, Council directed the APD to partner with the Racial Justice Coalition, a broad alliance of local civil rights groups, to craft a new use of force policy emphasizing de-escalation. Indeed, in the days after the killing, Hooper and multiple city officials touted their involvement with the RJC as a way forward.

But on Aug. 16 the RJC declared that it would no longer participate in the process as a whole (though some individual groups and members would), declaring the following:

We want to recognize the Chief’s willingness to work on use of force policies and appreciate her recent participation in a two-day Racial Equity Institute Training.

While members of the RJC have met with the Chief and agreed on including a number of community groups, and the use of an outside facilitator from the VERA Institute of Justice; we did not come to an agreement on all of the groups represented or the process involved.

Because we think it is important to continue to include community voices in the use of force policy review process, some of our members will continue to contribute as the process moves forward. However, we want to be transparent with the community that we were not in agreement with the final composition of the working group, and that this process is now being directed by APD rather than as a partnership with the Racial Justice Coalition.

Here too we’re faced with another case of contradictory explanations. At the Aug. 22 Public Safety Committee meeting, Hooper did not mention the RJC’s withdrawal at all and said the process was moving forward. The next day, when I asked for a list of the organizations involved in the use of force committee, Hallingse sent me a roster that included the Racial Justice Coalition. When I pointed to the Aug. 16 statement, rather than the APD clarifying the situation, I got this answer:

The vast majority of participants on the Community Police Policy Work Group were agreed upon by both the Racial Justice Coalition (RJC) and the Asheville Police Department (APD). Additionally, both groups do strongly agree on the importance of this working group and the feedback that it will provide. The group is diverse – including several representatives from the RJC and its member organizations, as well as representation from additional community social justice groups. Anyone not represented on the committee is encouraged to provide feedback to a working group member to be shared and included

A good piece in the Citizen-Times clarifies what actually happened. The RJC had pushed for the inclusion of representatives from SURJ and CPAC and some members became frustrated with what they described as police officials’ push to be too controlling and exclusionary, including in refusing to include those groups. There’s good arguments, as you might imagine, for at least giving both of them a seat at the table (Hooper, after all, pushed for the chamber of commerce to have a hand in crafting how the APD is allowed to use force). But SURJ occupied the police lobby and CPAC — while officially charged by Council with advising on police policy — has some members who’ve criticized the department’s conduct and processes. While some key groups, including Black Lives Matter and the local NAACP, remain involved in the process, the withdrawal of the RJC because of an inability for the APD to work with them as partners speaks volumes.

For community members who witnessed Hooper talk about law enforcement problems and issues of racial discrimination at a forum last year, or for those who took her calls for dialogue at face value, it’s a marked and depressing change.

The political math (and yes, a police chief’s job is as political as they come) isn’t hard to figure out here. The APD’s gone through multiple chiefs in recent years due to major internal and external issues. Given that history — and the positive response to the first months of her tenure — City manager Gary Jackson and Council really would like Hooper to work out well as the city’s top cop. A serious controversy or public rebuke would be a problem, especially heading into next year’s local elections. It’s possible for a senior staffer to read that political terrain as a free hand to do what they like for a long time to come, knowing that elected officials and the city manager will be very hesitant to call them out in any major way.

However, the duty of elected officials, and the manager and attorney they hire (and can reprimand or fire) require them to keep up scrutiny whether it’s day one or year 10 of their tenure.

At the end of the day, the buck stops with Council and they have the responsibility to halt this and demand a different approach. Fortunately, as I noted above, three of them have at least offered some concern about the actions after the protest and some of the following clampdown.

But far more is needed. Council sets policy, and what they need to set in this case is the message, loud and clear: “respect for civil liberties is a must at this job” because clearly, some of the APD’s leaders and the city attorney don’t believe that it is and don’t think anything will happen to them if they ignore it. If city staff believe that they can do what they wish, and our elected officials don’t check them, then our local government is fundamentally broken. If the elected officials who have so far remained silent endorse this harsher approach to policing protests, let them say so and the public can judge accordingly.

The bitter irony, of course, is that this heavy-handed policing, intimidation and petty retaliation is directed at protests that asserted that communities of color in Asheville too often face heavy-handed policing, intimidation and petty retaliation.

This is where Asheville’s problems collide with national ones. A recent report by the U.S. Department of Justice on the Baltimore Police Department attracted nationwide attention because of the endemic level of racism, harassment and brutality it revealed at that department (though importantly, many of Baltimore’s black community members had been pointing out the problems, and been dismissed, for decades).

But it pointed to something else as well, something very relevant locally, something that didn’t attract as much notice. The following applies event to departments without Baltimore’s history of blatant bigoted brutality:

Interviews with BPD officers throughout the chain of command also revealed that officers openly harbor antagonistic feelings towards community members. We found a prevalent “us-versus-them” mentality that is incompatible with community policing principles. When asked about community-oriented problem solving, for example, one supervisor responded, “I don’t pander to the public.” Another supervisor conveyed to us that he approaches policing in Baltimore like it is a war zone. A patrol officer, when describing his approach to policing, voiced similar views, commenting, “You’ve got to be the baddest motherfucker out there,” which often requires that one “own the block.” Officers seemed to view themselves as controlling the city rather than as a part of the city. Many others, including high ranking officers in the Department, view themselves as enforcing the will of the “silent majority.”

Whether every cop acts that way all the time is not the point. When a department has that kind of culture it will prevail more often than not, in ways large and small. The public, especially its most marginalized populations, will suffer accordingly. This whole sorry chain of actions described above has revealed that this mentality is sadly present among some leaders in the APD and our city. Even if they don’t personally hold those views too many are, at the least, unwilling to take serious action to halt it.

What happened after the July demonstrations could have simply been the arrests of seven protesters engaging in an act of civil disobedience, accompanied by their release on minor charges, something that’s happened plenty of times before in Asheville. The issues raised could have formed part of an ongoing and much-needed discussion over where our city goes and how we finally deal with issues going back many decades.

The actions of some of the APD’s leaders and the city attorney’s office, however, have combined to make it something else entirely: a clear warning to activists, journalists and even locals who might simply come out and hold a sign that they’ll be targeted. It serves as an indication to local groups that “dialogue” will only be tolerated if it reaches hollow, pre-determined conclusions.

I hope I am wrong about that, but too much that has happened since the protest continues to back it up, giving every indication of a push for facade and silence, not collaboration or change. As I write this, the APD is embroiled in another controversy, over video and eyewitness accounts showing an officer grabbing a teenager in the Hillcrest public housing complex and shoving her to the ground.

I hope the response — including to any protests or demonstrations — is a very different one this time around. If the direction of the July clampdown continues, then one day Asheville may find itself the subject of a similar paragraph in a future report, just another name in the litany of places where the government treats its own city like occupied territory.

—

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by its readers. If you like what we do, donate directly to us on Patreon or make a one-time gift to support our work. Questions? Comments? Email us.