How the city backed away from defending renters, the housing crisis fueled segregation, a climate of fear faces tenants and much, much more on a key Asheville issue. An interview with Robin Merrell, Parker Smith and Ben Many of Pisgah Legal Services.

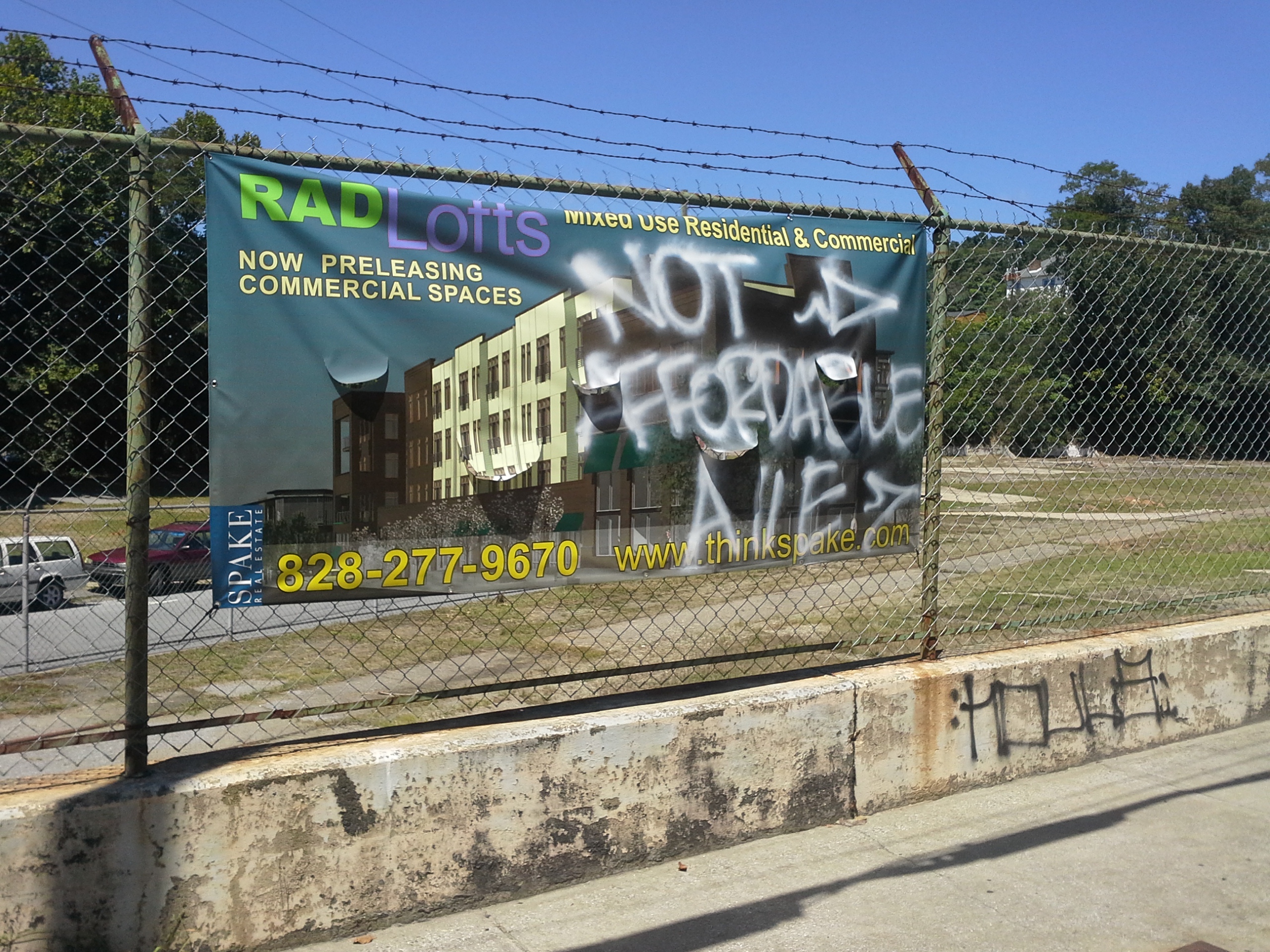

Above: Graffiti criticizing the RAD Lofts project, which controversially received city incentives in 2014 despite having few affordable units.

For 16 years Robin Merrell has been on the frontlines of fighting for affordable housing in Asheville. She’s helped locals fight unjust evictions and landlords as an attorney for Pisgah Legal Services and tried to craft policies to stem a worsening issue. As the housing crisis metastasized in recent years, Merrell became a major voice on the problem, both as a critic of the city of Asheville’s response and an early advocate of some ideas (like a bond referendum on affordable housing) local government ended up adopting. Here, joined by Pisgah Legal attorneys Parker Smith and Ben Many providing an on-the-ground perspective, they delve into multiple aspects of a crisis that still defines the lives of most Ashevillians.

Asheville Blade: How have y’all seen the affordable crisis and housing situation change over the years you’ve been working on it?

Robin Merrell: I’ve been working here for 16 years, and it’s been a problem the entire 16 years. But it seems to get tighter and tighter as time goes on. I’ve been one of the people who’s used the word “crisis” because I’ve long felt that people who need to take it seriously haven’t taken it seriously enough. I could see it coming and I could see it getting worse.

For a long time I felt that if we’re going to do something about it, people really have to see it for the problem that it is, and that housing is this fundamental foundation. If a person’s housing is not secure, nothing else in their life is secure. We know that there are these terrible effects on families and children, that each time a family is evicted a child loses four months of progress in school. If that happens a few times a year, and it does to our clients, then kids are behind in such a way they may never catch up. Those are long-term effects for all of us.

I see more elected officials paying attention to it now than ever, and I see Asheville trying and Asheville doing some innovative stuff, Asheville doing some stuff I’ve recommended they do. But we’ve still got so far to go. It can get discouraging to just watch the problem grow and progress as time goes on.

Ben Many: I can definitely say it’s not better. Every year seems to bring about different challenges. A couple years ago when we had a couple of cold snaps, it was the year of people in trailers pipes freezing. If you’re evicted in Buncombe County in the next couple of years, you’re going to have a really difficult time finding suitable housing. You’re probably going to wind up in a trailer somewhere in the county, not the city.

Obviously this is anecdotal. We keep tabs on what we see, but we don’t see it all, we see what comes through our doors. I worry, sometimes, that some of the most vulnerable, don’t feel like they can get to us or don’t know about us, particularly undocumented populations. There are horror stories about what happens to them, some of which we get wind of. There was a place in Henderson County a couple of years ago where a guy was packing as many undocumented people into trailers as he could, charging them by the head and it wasn’t cheap. But you can see why, especially in this climate, why no one would want to come forward and say “hey, let’s take part in the justice system.”

Does this desperation create a climate of fear? That obviously hits more marginalized populations worse. Has it gotten worse, especially since the election?

Merrell: I think we already had this climate of fear where people were afraid to complain about their housing conditions or complain about being charged illegal fees or too much of a security fee or a daily late fee, things that weren’t ok, because if they were evicted, where would they go?

We see people who have put up with sexual harassment, no heat, serious plumbing issues, big holes in their floors, because they’re afraid to complain, they’re afraid of displacement.

Parker Smith: It’s a valid concern because of the housing stock being what it is. If they do complain and they do get evicted they may very well not have anywhere to go.

Many: I think these are broad problems all over the country, but when you’re ina spot where there’s just not as many options, it adds to the difficulty.

Merrell: But there are states with stronger tenant protections than North Carolina, our retaliatory eviction law is very weak.

Many: Very weak, you can’t use it as a sword, only a shield and the shield’s got some holes in it. I think if anything it’s more preventative than being really effective in court.

That brings up something I’ve heard in recent years, a fear of even speaking broadly about housing conditions, of even saying ‘hey, housing’s not that great and I struggle with meeting the cost of housing’ that they will be evicted for that, for getting involved in basic activism. Is that something y’all encounter?

Smith: I think so. We get calls all the time from clients who have no heat, have had a broken window for two years and just want to know what their rights are. When we talk to them a lot of the time they say “ok, I just wanted to know what my rights were, but please don’t call my landlord, please don’t do anything.”

Many: Don’t rock the boat.

Smith: “Don’t rock the boat” is a big one we hear.

Many: I’ve got a couple right now saying “don’t rock the boat” despite the fact they’ve got pretty good claims.

Smith: They do, but I can understand where they’re coming from since there is, especially in Buncombe County, doubly so in the city of Asheville, not really anywhere for them to go if they do end up evicted.

Earlier there was a mention that there has been some progress made and that some policies have worked. What do y’all see as some of the policies, at the city level and on the ground, that have worked and haven’t worked?

Many: it is important to understand that municipalities in North Carolina are very limited, they are very much creatures of the state. So a lot of very modern growth principles that other places can use, we can’t, as the city is so limited by state statute.

There’s also a concern from the city that if they push too far on any one thing, the general assembly will jump all over it and take away any authority they do have. I think we saw that happen in Charlotte [with HB2]. We’re interested to see what happens with this bond.

Merrell: One thing the city has done well is its housing trust fund program. There has been a measurable amount of affordable units put on the ground because of that program. Not enough, but we’re about to see this influx of cash into the trust fund that’s never existed before. We hope developers are going to take advantage of that. What we want to do is learn what that’s really going to look like, educate the community and developers and encourage them to take advantage of that program.

[Turning to Smith] You want to talk about something the city’s not doing well?

Smith: They are not enforcing the minimum housing code and I think that ties into the issue about tenants not wanting to complain about conditions. I don’t think it should be on the tenants, completely, to complain and monitor and hold the landlords accountable in Asheville. We have a minimum housing code that doesn’t have any teeth so even if they find violations, nothing’s getting enforced, there’s no incentive for a landlord to actually make any repairs.

Many: It’s much easier for a tenant to get an inspection in the county than within the city limits.

Why that difference?

Merrell: With the county all that has to happen is a tenant calls the fire marshal’s office and says I’m a tenant and this is what’s going on. If it’s something they believe is within their code, they schedule an inspection and they come out and look at it. If it does violate the ordinance they [the county inspectors] go through the steps of notifying the landlord, giving them time to correct it, those sorts of things.

In the city, for one, it’s not clear who you call. When we call those numbers, no one calls us back. If someone does manage to get ahold of a person, they get asked ‘have you told your landlord?’ In writing, can you prove you told your landlord? Have you given your landlord 30 days?

The way I see it is it’s actually putting a requirement on the tenant that is not in the ordinance. The ordinance does not say you have to give written notice to your landlord.

Many: But it is the practice.

Merrell: State law doesn’t say it either. 42-42 A1 is very clear that a violation of a municipal or county ordinance is a violation of state law and it does not require written notice.

So the key difference is that the city is expecting this extra burden on the tenant, where the county will just send out an inspector?

Merrell: Correct. To give it some context the city used to have one of the most progressive and best-enforced ordinances in the state. Back in 2003 there was a review. Both Jim Barrett, our executive director, and I sat on the review committee. It was very much a political process and that was when some major watering down of both the standards and the enforcement happened.

Since then we’ve just seen this snowball effect of the city not enforcing the code to the point that it’s completely ineffective.

[Indeed, neither the city’s housing ordinance or state law require a tenant to notify a landlord before a local government inspects housing, so this is a practice chosen by city staff. The Blade asked the city of Asheville about their enforcement process. According to Mark Matheny, the city’s Chief Building Official, “a request is made for the tenant to communicate with the landlord about the issue. The City requests that the tenant communicates about the complaint in writing to the landlord. A site visit is scheduled once the City gets a copy of the written communication from the tenant to the landlord.”

I asked for further clarification and received the following from a city spokesperson:

“The City of Asheville began a practice of having tenants notify landlords via written notice as far back as 2004, when these types of complaints were handled by the former CoA Housing Division. The practice continues today through the current Development Services Department.

Although, DSD strongly encourages tenants to notify landlords before notifying the City, in order to allow them a chance to rectify a situation, a City inspector will still do a site visit if the tenant declines to notify the landlord first.

— D.F.]

I take it this has been pointed out to city staff. What has been their reaction when that has happened?

Merrell: Over the years we have found a varying degree of interest from city staff. Some people have been very upset. Others don’t seem to think it’s a big deal. There is an overwhelming sense of ‘I’m following orders and this is not my problem.’

When we’ve talked to city attorneys — and I say city attorneys because it was not the main city attorney that I had this conversation with — we didn’t get far. There was some defensiveness and in general a lack of interest in changing the ordinance in a way that will keep more tenants safe.

After the GOP took over the general assembly, there was some change around what cities could require enforce as far as housing codes. How does that actually constrain a municipality? It sounds like some of this from Asheville is local. I know the watering down of the ordinance took place way before the state ever passed those laws.

Merrell: The state laws that have changed certainly have an impact on the city and on the county. They narrow the authority a bit, but they also still preserve the right to have a code and enforce a code and for the standards to be health and safety related. The state changes aren’t great from our standpoint, but they don’t hinder the city from having a robust housing inspection program if they want to.

What would a more robust enforcement program look like from the city’s end? Would it look more like the county’s?

Merrell: Well the county has some room for improvement as well, but it is better. I think that a broad campaign of both landlord and tenant education is warranted, so both property owners and renters know exactly whose responsibility it is for what and for the city to say ‘we have an ordinance, we’re going to enforce that ordinance. Here are your obligations. Tenants, here are your rights, if they are not being met then you can call us.’ To me that’s what a robust program looks like, and then for it to have enough staffing so that when people call they can respond.

Also: following through on inspections to ensure that repairs are being made. Then, if it becomes necessary, going to court and being willing to testify. That could happen in a couple of ways, it could happen if the tenant has a claim against the landlord about long-term, serious violations that have caused harm. But also, going back to what we talked about before with the tenant fear. If the tenant complains and then the landlord files for eviction, having that inspector come in and testify as to ‘I got a call on this day, I inspected on this day, landlord did/didn’t make repairs’ would frequently give the evidence that the tenant’s being evicted and that would stop their eviction for a year.

You mentioned earlier that the housing trust fund had worked out and now it’s got the bond funds in it. What are some other steps the city could take to improve the housing situation?

Smith: I would like for the city to prioritize low-income housing over, or at least in addition to, workforce housing. What I hear a lot are prioritizing housing for people moving to the area and I think we’re forgetting about people who are already in the area and already working here and struggling to find affordable housing or stay in their housing.

We had the one percent vacancy rate across the board and that’s improved, it’s two to three percent, which is still not great. That increase in housing stock is not for the low-income population, it’s not for the people that need it most. It’s not for the person that has no running water, is afraid to tell their landlord and doesn’t have anywhere to move if they get in trouble with their landlord. What I hear a lot is “why don’t people just tell their landlords?” or “why don’t people just move?” That misses a huge part of the problem, which is there’s nowhere to go.

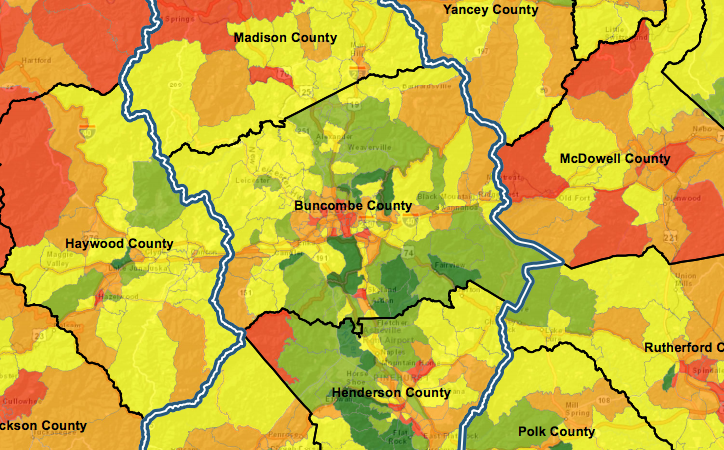

A map of city areas by median income, from the 2014 Bowen report. Red areas have a median income under $30,000 a year, orange areas under $50,000.

It also seems like that assumes a level of faith in the landlord and a level of money that the person has that is not always applicable.

Smith: Right. I want people to understand that our clients don’t enjoy living in these conditions. They don’t, they just don’t have anywhere else to go. They’re having to come up with security deposit, first month’s rent, you have to save up money to do those things. That’s not necessarily something our clients can do. So when these landlords see they can raise the rent, they can charge so much more above fair market because of people wanting to come to Asheville, it creates this problem for our community and the people that have been here.

So despite the uptick in vacancy rate, the level of desperation and issues with landlords and tenants haven’t decreased measurably. They’re still there?

Smith: Yes, especially among a low-income population there’s still a housing crisis.

Merrell: We need to clarify that there are lots of really great landlords out there, but people who call us are in crisis and are frequently taken advantage of by a number of unscrupulous landlords that operate in this area. Being a landlord is like being an attorney, the bad ones really color the opinion of all of them. The good ones suffer for that.

Does the overall shortage and high housing costs create a more conducive environment for those unscrupulous landlords?

Smith: Without question it does. They are able to make money and profit off of the situation these tenants are in, that there’s nowhere else for them to go and someone is going to choose a house with no running water over having no home at all.

The increase in the vacancy rate has been touted by some in Asheville and on Council to the point that it was said during one of the housing debates last year that the housing crisis is only “perceived.” There was this crisis moment when the Bowen report hit, many city leaders acknowledged it as a crisis. Is there a danger now of potential complacency?

Merell: Absolutely there is, the notion that there is no longer an affordable housing crisis and that it’s perceived is one of the most insulting things I’ve ever heard and is also completely and totally erroneous.

Smith: It’s wrong, it’s just clearly incorrect based on what’s happening to people in our community.

Merrell: It is wrong and to me it’s sort of that comparison of when the word changed from calling it “hunger” to food insecurity. Tell that to the kid with nothing to eat. They’re hungry, they’re not insecure about their food.

In this situation people don’t have a decent place to live and it’s not a perception. Anyone who thinks that it is should open up their spare bedrooms and let some homeless people come live with them.

Smith: People with Section 8 vouchers can’t find anywhere to rent because there’s nowhere available.

That’s a good question, how does the Section 8 voucher situation get affected?

Smith: People can’t find anywhere to use their vouchers because they do have the requirement to be used at a place with fair market rent. Since that’s not the housing stock that’s available here in Asheville, you have people whose vouchers expire because they can’t find anywhere to use them.

That is one thing I wanted to clarify: so it’s not that places aren’t taking Section 8 vouchers, it’s just that the rents are so high that they can’t legally be used on it.

Smith: Exactly, that’s what my clients are finding.

Merrell: There are some people who will say they don’t take a Section 8 voucher. There are, possibly, that there are people who inflate their rents so they don’t have to take a Section 8 voucher.

The city’s embarking on an overhaul of its development codes. We’ve talked previously about the workforce housing issue and about a year-and-a-half ago you mentioned the zoning needs to change, that has been a part of this housing crisis. How has that played into the housing situation and what are some changes the city might consider pursuing?

Merrell: I have heard from developers for years, some of whom straight-up say they will not build [housing] within the city of Asheville due to the constraints. That kind of speaks for itself.

Constraints might not even be the right word. The bureaucracy, the process being too long and too cumbersome. I even hear it from churches and businesses downtown that the idea of adding an outbuilding or fixing a sidewalk is not simple. It’s long and it’s expensive.

Anytime a requirement is put on development that extends the time or the cost, that gets passed on to the consumers of that development. If we want affordable housing we have to make the process for building it as easy, quick and inexpensive as possible.

We don’t want developers’ money spent on architects’ and lawyers’ fees. We want their money spent on producing a quality product that’s affordable.

One of the other issues that has come up is the potential impact, in a hot tourism market, of short-term rentals on already very expensive market. Is that a concern? Is that something that could be a contributing factor to the crisis if it continues or increases?

Merrell: It is. Anytime a unit is taken out of the rental market and put into the short-term rental market than that’s one fewer unit we have.

It gets back to something Parker talked about before. Do we provide housing for people who are coming here or do we provide housing for people that are already here.

Is it something you’re seeing as a concern on the ground? Are people saying ‘hey, my landlord’s going to evict me because they want to make a short-term rental?’

Smith: I’m not seeing the short-term rentals come up. What I’m seeing is tenants who are being evicted because their landlords want to sell, or because they want to tear down what’s there because it’s in such poor shape and then turn around and make money.

Merrell: What I’ve heard from some community members are people who are more middle-income who are finding themselves losing their housing for it to become short-term rentals. It happened to the person who used to be our IT provider.

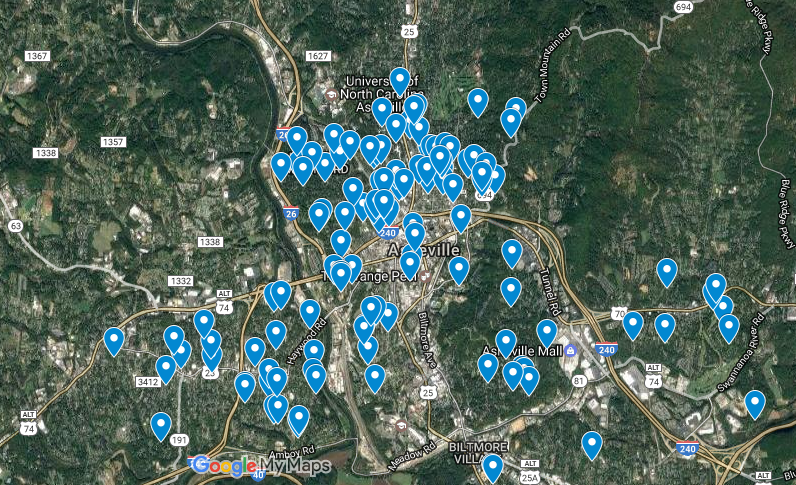

Sites hit by city inspectors for violating local prohibitions on Airbnb-style rentals in many neighborhoods. The practice has fueled fears that it may make the affordable housing crisis even worse. Image from a map project produced by the Blade.

Smith: I think that’s primarily because , in the case of many of our clients’ units, if anyone listed them on Airbnb, no one would pay to go there. But I have had friends who have been evicted with landlords wanting to turn them into short-term rentals. That’s kind of frustrating, because it’s often people who are out of state, who bought a house and are now renting it out as short-term rentals so there’s nobody in the community.

Is density something the city needs to look at encouraging more of, and to what degree?

Merrell: Back before I got here the city adopted the UDO, that decreased density within the city limits by about half. It only seems reasonable, from a mathematical standpoint, that increasing density provides more units and that if we had higher density in the past, we can have higher density again in the future. I think the city has been looking at increasing density in some districts in the last few years.

I think it’s wise and strategic to look at increasing density along transit corridors, to create this continuum where you have extremely high density, then density decreases until you get to the single-family neighborhoods. But with there being plenty of space for higher density. The city can’t just be a city of single-family residences.

What do y’all see as the biggest obstacles to changing that?

Merrell: There are several obstacles to increasing density. We have to understand the topography where we are is mountainous and we can’t have great density on mountainsides, because then they just slide off.

But in many neighborhoods there’s an element of the NIMBYism that still exists. People become afraid of the unknown, of who might move into their neighborhood, of how their neighborhood might change, how their neighborhood might look with more people and more structures in it.

I think that everyone is fine with affordable housing being constructed somewhere else. But it’s when we have to think about it being in our own neighborhood it becomes a different thing.

Larchmont apartments on Merrimon Avenue are a huge example of this, where they went into this great space between the businesses and neighborhoods. A lot of people were opposed, a lot of people said it would change the characteristics of their neighborhood and it hasn’t. It’s almost like it was always there or is barely there at all. It just hasn’t changed things.

It’s a good example of both how people feel about density and then what can be the result of density when it’s done correctly. I think that there has to be some political will around increasing density. That will may well be there in the city.

We’ve seen numbers coming out of the State of Black Asheville about the level of de facto segregation in Asheville, it’s even worse than many other North Carolina cities. How does this overall housing situation contribute to that?

Merrell: I was at the [Buncombe] County Commissioners’ [Feb 21] meeting and I saw Dr. Mullen’s presentation. It was the sort of presentation that both makes me angry and makes me want to cry. What we see as our reality is that people of color tend to live in certain neighborhoods in the city and certain areas of the county. They don’t live in the others really at all.

I think that within the city limits especially, there’s this perception that “all the black people live in the ‘hood’ a.k.a. public housing and that as long as we keep them there, away from the rest of us, it’ll be ok.” We’ve worked with thousands of clients who live in public housing. Universally, they want a decent place to live. Many of them want to have the ability to leave those communities. The way life is right now they’re not getting those opportunities. Maybe it’s because no one will take their Section 8 vouchers or no one is building housing that they can afford in all areas of the city and the county.

We know that people of color are disproportionately impacted by the affordable housing crisis, we know single women are disproportionately impacted by the affordable housing crisis. Therefore, children are disproportionately affected. When we don’t create housing for those folks then we perpetuate segregation.

Is there anything else you’d like to add?

Frequently we only get to highlight the problems, we need people to understand that people living in a housing crisis don’t have the opportunity to tell you about it. They tell us because we’re in crisis. But we have to help spread their voices and their stories.

—

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by its readers. If you like what we do, donate directly to us on Patreon or make a one-time gift to support our work. Questions? Comments? Email us.