Old wounds, segregation, a lack of transparency and skyrocketing costs all collide as the city’s ambitious plans to overhaul the river district flounder

Above: A painting from the cover to the 2004 Wilma Dykeman Riverway plan, depicting part of the imagined future River Arts District.

The French Broad cuts, from a birds’ eye view, just west of the city core. A century ago, like many rivers, its bounds were packed close with industrial works: factories, tanneries, railyards. Like many it was also bordered by redlined neighborhoods left to deal with the consequences of segregation both economic and environmental, hit even harder by urban renewal that pushed out or robbed whole communities.

It was unique in some ways too, one of the only rivers on the continent flowing northeast, the French Broad attracted dedicated advocates like famed writer Wilma Dykeman and the environmental activists who started the decades-long work of clean-up in the ’80s. It also attracted the attention of artists, taking refuge in cheap if crumbling spaces. Graffiti and street art sprang up.

Then came the businesses, the breweries, the deals and the sales. The marketing and merchants’ associations. The pushing out of the marginalized, the local and the artistic. All the familiar signs of gentry deciding that the place was now ripe to make “just so.”

Everyone seems to see something in the river, so out come the plans. City plans, private plans, business plans. Plans for future plans and plans about plans. Plans to counter gentrification and plans to profit from it. Everyone agreed there was something special there. Over the years — and now — they often agreed on little else.

Even the names of the area bore the mark of old wounds. The urban renewal plans that devastated the local African-American community dubbed the whole swath “East of the Riverway,” a term the city has still uses on its plans, while the largely black communities nearby call their neighborhood Southside. The official artists and architects’ renderings of the potential future depicted a gleaming, tourist-friendly area that often leaves humans out entirely. When the renderings depict include them at all, it’s often as a gentry impressionist’s fantasia: sunny, shiny to the point of wash-out, blithely affluent and very, very white.

But the many people left out of that vision didn’t stay idle. Southside residents increasingly organized to demand to a voice, and that the city’s attention turn to addressing their long neglect and exclusion.

To the city of Asheville and the elected officials in charge of governing it, the river was also an opportunity, and one they usually emphasized for reasons of economics (with some references to justice thrown in). Downtown Asheville, with its revival of once-abandoned buildings and its dense residential and commercial activity, had boosted Asheville’s profile and the city’s revenue. With their annexation powers curbed and Asheville facing major issues of its own due to the city’s limited ability to get funds directly from the tourism boom, perhaps — the thinking went — lightning could strike twice. Over the past 15 years, emphasis repeatedly turned to the river.

Innovation district, business attraction, tourist hub, beer destination. All those images glittered in the minds of city officials, folded the ideas centered on improving Southside’s long-neglected infrastructure into a plan to bring together the many disparate official proposals for the area, to overhaul the district’s infrastructure, especially the parts friendly to breweries, arts destinations and tourists.

They dreamt of plazas around old smokestacks, a visitors center, the site of the city’s stormwater control offices, a recreation hub and graffiti replaced with public art (carefully chosen by the city, naturally). a place appealing enough that businesses and wealthier residents would pour their resources into it.

So the city sought — and found — partners, and assured the public that behind the acronyms like RADTIP and TIGER lay a glorious (and sure, more just and a bit less segregated) future for Asheville, the largest infrastructure project local government had embarked on in living memory, the jewel in the crown for Council and officials alike.

They found something very different. As 2017 wore on, those capital letters instead became a byword for a mire of skyrocketing costs, opaque dealings and, once again, the neglect of a neighborhood.

TIGER by the tail

It comes down to infrastructure. Indeed, this is one of those cases that shows how that word can seem far too bland when the reality of “can people in your community cross the street without dying?” lurks behind it. The river — its promise, profit and segregation — revolve around infrastructure.

The Wilma Dykeman plan, focusing on area directly around the river itself, dates back to 2004 and includes street improvements, bridges, greenways and more. Devised by the Riverlink non-profit that played a key role in cleaning up the French Broad, along with local officials, it was an attempt to tie improved public space, environmental rejuvenation and a desirable area for artists, businesses and locals alike.

But the community’s harsh divides also remain apparent in infrastructure. While Dykeman fought segregation the district intended to be remade in her name still bears its harsh hallmarks. Crosswalks and pedestrian improvements, a roundabout and medians sporting green bushes sprang up as the River District gentrified, only to stop at a line as Depot curves towards Livingston.

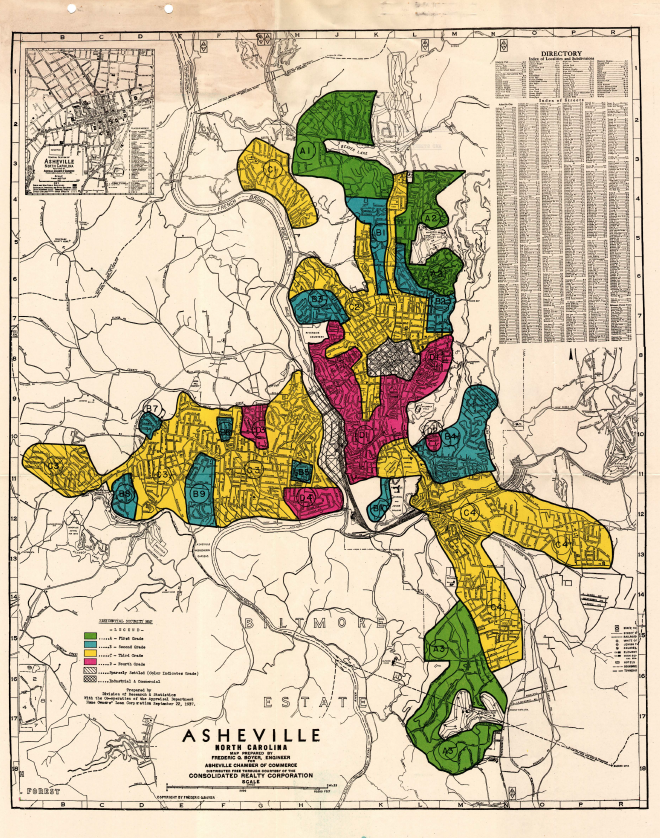

The 1937 HOLC map of Asheville. All but one of the areas marked in red — including the areas near the French Broad River — are majority African-American and were targeted by devastating racist government programs in the decades that followed. Image via Mapping Inequality.

As one goes towards Livingston Heights, such things disappear almost entirely — with just one thin walkway near the Edington Center — reappearing only when one reaches the cluster of doctor’s offices near Mission Hospitals. Much about our city’s segregation problems remain below the surface, but sometimes the divide is starkly apparent even to strangers driving through.

In recent years however, locals including groups such as the Southside Advisory Board, longtime residents and public housing representatives pushed for redress. They sought rebuilt community centers, a renovated pool, better infrastructure and for a far greater say and role in their own communities. City officials did not always respond well to those efforts, and how much the city is actually willing to do remains a source of serious controversy.

But governments from the local to federal level started, with extreme belatedness, to claim that they recognized the scale of the problem. Both the city and the EPA did studies on the impacts of and alternatives to gentrification in the area. Starting in 2014 they pushed for improvements around Livingston Street, to hopefully improve pedestrian safety and connectivity in the area.

But the plans ended up becoming something quite different, and far more expansive than just reversing that sliver of racism and neglect. The city sought — and received — $14.6 million in federal TIGER funds from the Federal Highway Administration. The Tourism and Development Authority, the consortium of hospitality industry magnates that controls local hotel tax revenue, also put up $2.5 million. The largest chunk of the costs — $26 million — would be borne by the city. The project didn’t just center on the Livingston Street improvements, it also included many parts of the Dykeman plan, as well as improvements to intersections, sidewalks, bridge changes (that would make the area more accessible to commercial and brewery trucks) multiple greenways and a visitors’ center.

Then-U.S. Secretary of Transportation Anthony Foxx announced the grants in late 2014, intended to “complete an interconnected six-mile network of pedestrian, bicycle, roadway, and streetscape improvements” alongside city officials.

“With the help of TIGER, Asheville residents and visitors will soon have even greater access to their community with the ability to bike and walk the city’s streets more safely and securely than before, including the roads near the French Broad River and in the Southside neighborhood,” he declared.

“The plan is coming together,” Mayor Esther Manheimer told the Blade at the time.

It was ambitious, certainly — one of the biggest infrastructure projects the city’s ever embarked on — and Manheimer and other city officials touted it as a way forward, the next stage in Asheville’s development. RAD was even designated one of the city’s “innovation districts,” ripe for investment. If the city could pull together these kind of partnerships in the RAD, the reasoning went, they could use the same model elsewhere, handily revamping Asheville’s aging infrastructure, bringing in a boatload of cash and maybe defraying a bit of its de facto segregation.

The years marched on, and city staff went about preparing the massive groundwork for such a project, honing the design on each part, holding meetings with “stakeholders” (and the public) and planning its budgets for the massive undertaking. Last February they even put up a video of what the future Livingston improvements would look like.

In December, city officials hired Beverly Grant/Barnhill to handle “pre-construction work including bidding, disadvantage business outreach, and advertising.” In the nearly three years since the TIGER announcement, construction costs had certainly risen, and the company told the city that RADTIP would now require $6 million more (the amount was included in this year’s regular city budget), bringing RADTIP’s total costs to $56 million.

This spring the final bids came in, from just two companies. Under state law, the city had to put the matter back up for bid. They did. Again, in mid-May, two bids came back.

The city manager picked one: Beverly Grant/Barnhill.

Despite the very same company handling the bidding process for a project that — six months earlier — would supposedly cost $56 million, it now wanted $76 million for the job.

This was, to put it mildly, a big problem. It didn’t stop there.

The company’s bid didn’t include the Livingston Street improvements; supposedly one of the main reasons for RADTIP in the first place. At Beverly Hanks/Burnham’s suggestion, to “provide the project with the greatest flexibility in determining how to award the work in a difficult bidding environment” RADTIP was split into six separate pieces for the bidding. No one bid on the Livingston Street segment.

But if city officials sprang into emergency mode, they declined to tell Asheville City Council or, importantly, the public (though Manheimer later revealed staff did meet with some property-owning “stakeholders”).

The final bids came in during mid-May, during the most contentious budget season in memory, and right before a major public hearing on that budget. But while police expansion, bond money, taxes, transit, a hidden staff salary hike (with extra raises primarily going to top officials) and energy initiatives all came up for discussion, the massive cost change in RADTIP did not, because senior city staff kept it to themselves.

Indeed, the first time Council was informed by senior staff that the biggest project on their watch was in massive trouble was early June, when Assistant City Manager Cathy Ball sent out a brief email.

That’s it. No “heads up, this is a big problem and we’re trying to figure out what to do about it,” no “let’s discuss this during the next budget session” (Council had one before its May 23 meeting), no “meet with us ASAP to get a briefing and discuss options.” Council didn’t receive formal notice — in the form of two-member meetings with senior city staff — until June 19-20, almost a week after the budget had already passed 5-2 and just a week before their next meeting.

Asked about why Council wasn’t quickly informed about such a key matter, Ball tells the Blade that staff needed to understand the federal response first before informing Council or the public of the massive problems their biggest project had encountered. “We needed to get a feel for what they felt like before we could present to Council with any options that we had.”

Why did construction costs skyrocket so much? “I think it’s a lack of bidders, the cost of work and some of its the three-year window of the project, there’s a lot of unknowns that could happen over that time period, with the cost of gas or the materials they might need.”

The project’s sheer scope, she claimed, also meant that there simply aren’t that many companies nearby that can do it.

So staff started sheaving off parts of the project, road improvements at both ends of the RAD, the Town Branch and Bacoate Branch Greenways and French Broad River Greenway West were all now on the chopping block, to be “phased at a future time.”

On June 27, the matter finally came before Council, and staff was seeking another $6 million to make a stripped-down version of the project possible. Deadlines loomed.

“City staff have met with community stakeholders regarding the future phases of this work and are committed to continuing the discussion about the project development. Additional efforts will include a citizen engagement process,” staff’s memo to Council read. “Through this process the community will continue to stay involved and have input into to the continued project development in the River Arts District.”

‘Radio silence’

Vice Mayor Gwen Wisler sharply criticized staff for a lack of transparency around major cost overruns. file photo by Max Cooper.

“TIGER VI is entering the room, I wish we had walk-in music,” Manheimer said as the RADTIP issue came before Council on June 27, to the laughter of her colleagues (though City manager Gary Jackson and Council member Gordon Smith were absent).

“What you’re being presented with is really a big deal, it’s a major milestone in the city of Asheville’s riverfront redevelopment program,” Stephanie Monson Dahl. “This project is the largest, most comprehensive — and also the costliest — project in the city of Asheville’s capital improvement program.”

She noted the swath along the river was equivalent to the distance from the Masonic temple to Biltmore Station and that RADTIP was based on the concept that the many, many things the city wanted to do in the area “do not compete with each other.”

“This is becoming quite the place where people want to see local businesses succeed,” Monson Dahl continued.

But “there is a cost to developing in this area,” she continued, and not just a physical cost but an “emotional cost,” with staff having a “certain level of disappointment” but with the current budget were unable to build the original projects.

To make a long spiel short: staff needed another $6 million for a pared-down version of RADTIP that left out a good chunk of greenway and road improvements and ditched one of the core reasons for the whole project — proper infrastructure on Livingston Street — entirely.

Vice Mayor Gwen Wisler however, despite being enthusiastic about RADTIP (“an exciting project with a lot of potential”) had some major problems.

“I am really disappointed and frustrated by the large budget overruns, driven by concerns around transparency and equity,” Wisler said. She had questions “driven by concerns around transparency and equity. The public input on this project has been stellar, up to a point. Staff’s consistently gotten input from our boards and commissions, held public meetings, asked people to weigh in. Then when the bids came in it felt like radio silence.”

“Why didn’t the staff let Council and the public know about the size of the overruns and allow the public to weigh in on the portions of the projects that were being delayed and how that selection was being made?”

One of the major points of the project, she emphasized, was “connectivity of some of our underserved communities to economic opportunity and other community facilities. How was that overriding equity issue addressed?”

Indeed the plans to improve Livingston Street, or the equity aspect, weren’t even mentioned in either the staff memo (which emphasized the aspects of the Dykeman program RADTIP would still fulfill) or Monson Dahl’s presentation.

Wisler wanted to know if there was any opportunity to delay the decision to allow that input, and to have far more transparency in the future. She wanted staff to update the Finance Committee on these major projects more routinely.

“I think your questions are fair,” Assistant City Manager Cathy Ball said. “When we received the bids, and that was a matter of less than five or six weeks ago, our primary concern was how to work through the FHWA to maintain the $14.6 million.”

Without that cash, she said, the whole project started to fall apart.

She claimed that the federal grants were based around helping “underserved, the lowest socioeconomic area in the whole city,” and the pared down projects retained the core of that. Access to greenways, for example, remained preserved. Livingston Street imporvements, the cornerstone of the equity effort, was off the table because it hadn’t received any bids, but remained a “high priority.”

“Given the dynamics of a changing world in Washington, we were very concerned about being able to move fast and get this funding secured.” All were “guided,” she claimed, by the previous community input they had received.

The city had to keep the Tourism Development Authority on board as well, to make sure it could keep $2.5 million in funding from them.

“Having not had that information, I can understand why people would be worried about the radio silence,” Ball said. “But I assure you we worked in every way we could to guarantee this community would get the funding for this project.”

She laid out a situation that, despite Council and the public’s shock, put them between a rock and a hard place due to staff declining to notify them for weeks: if they didn’t “turn dirt” on Aug. 1, and approve the funding before the start of July, the whole endeavor stalled.

But in the future, she said, staff would happily go before a Council committee for more regular updates.

“The question is: how could you get so surprised by the bids?” Council member Cecil Bothwell said.

“We were very surprised to turn around only six months later and receive bids that are $20 million above that,” Ball emphasized. “There is a lack of competition in WNC for this kind of work.”

But, she said, staff were brainstorming ways to divide up the remaining parts of the project so that small businesses could also bid on them.

“So the choice we have tonight is to approve this or give up $14.6 million federal dollars” and the TDA funding as well, Bothwell noted.

Council member Julie Mayfield said she’d heard from the public that “we’ve chosen the wrong things,” cutting greenways, for example, when they were popular with the public. Ball replied that if the city had prioritized the greenways, they likely would lose the federal funding.

Manheimer praised staff and the fact they had talked with “the key stakeholders, the people who actually own property” before deciding how to pare RADTIP down. She was “shocked” by the bids, but emphasized staff was too.

During public comment the speakers, with the exception of one who sharply criticized staff for not anticipating the construction costs, mostly called on the city to not pare down the Lyman Street greenway, worrying that a lack of bike lanes and adequate size could make it less safe. This included former Vice Mayor Marc Hunt and representatives of several local groups. Council agreed. Council candidate Kim Roney criticized a lack of public outreach and noted that the upcoming opportunities for working people to weigh in were limited. Council gave no response.

They did, however, approve the stripped-down RADTIP, passing the $6 million with no dissenting vote.

After the meeting, reactions split, and the floundering of RADTIP promises to be an election issue. Bothwell (who’s running for re-election) defended staff in some statements on social media, saying they adapted well to an unexpected situation.

Not everyone was so sympathetic. Council candidate Vijay Kapoor, who consults with local governments on economic and financial matters, issued a statement harshly criticizing of the entire process that “has left me stunned and concerned about Asheville’s commitment to good management, transparency and equity.”

He asked why Council and the public weren’t informed, why Beverly Hanks/Burnham was allowed to bid on the same project it helped set the terms for and why the estimates were so badly off.

Indeed, whichever view one takes, the RADTIP woes raise major questions about the costs and hazards of the city’s preferred method for overhauling neighborhoods and changing infrastructure — as well as how seriously it actually takes addressing the impacts of redlining.

As for the Southside improvements, one of the main reasons for RADTIP’s existence in the first place, their fate remains uncertain. At one point in the June 27 meeting, Mayfield asked about a desperately needed crosswalk in the area. That, staff said, will still go forward.

Manheimer said that Livingston needed to be a priority, “it’s a very important piece,” but agreed with staff that Council would take it up next year at the earliest.

Still, with rising construction costs, she added “I don’t think it’s going to get better.”

—

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by its readers. If you like what we do, donate directly to us on Patreon or make a one-time gift to support our work. Questions? Comments? Email us.