The Airbnb wars take a decisive turn as Council passes a new ban in an attempt to halt a wave of housing losses

Above: Asheville City Council member Vijay Kapoor, who asserted that the nearly-citywide ban on whole home/apartment Airbnbs was necessary due to the industry’s rapid takeover of housing units. Photo by Max Cooper.

The housing crisis isn’t new. Asheville’s status as a deeply-segregated tourism hub with a perpetually-underpaid working class has fueled various forms of desperation and injustice for decades. Its compatriot shoving out of people and cultures in favor of more gentry residents, aren’t new.

But in the last few years the explosion of Airbnb-style rentals added a harsh new wrinkle, one that would grow, as the industry did, into a massive political fight.

In the view of those with an extra property (or four, or five…) to hock out to tourists, the change was a godsend, a chance to get the type of tourist cash hoteliers had been wallowing in for years.

But from the view of affordable housing advocates and many renters (over half the city are tenants) facing already expensive costs to keep a roof over their heads, it was the equivalent of throwing gasoline on already raging fire. While there were occasional cash-strapped homeowners that rented out a room, the booming industry tilted far more in favor a very different class of property owner. A whole home or apartment in a tourist town suddenly became a hot commodity, and visitors looking to spend cash could pay a lot more than a local worker. Those with multiple properties (and the funds to hire cleaning and management companies) were ideally set up to cash in on the boom. They did.

The fight split plenty of property owners too, sometime on the same streets. Those who viewed it as a profusion of mini-hotels wanted the industry reined in. Those who thought they could profit from it wanted the rules loosened. Both groups took their cases to Asheville City Council.

Renting whole homes/apartments to tourists has been illegal in most of the city’s residential neighborhoods for as long as the city had modern zoning, but in practice the restriction was haphazardly or barely enforced. In 2015, as pressure mounted, Council upped fines and enforcement on that business (technically known as “short-term rentals”) while relaxing rules on homestays (the technical term for a resident renting out a room or two in a home they live in).

There was just one catch: short-term rentals remained legal in key areas like downtown, the River Arts District and Haywood Road. The displacement this created wasn’t news, Joy Chin’s ground-breaking early analysis of the Airbnb industry, published in the Blade early that same year, highlighted it as a key problem. The article even sparked some Council discussion, but if city leaders felt any urgency to act, they didn’t show it.

Despite the 2015 laws, the Airbnb lobby continued to loudly press for looser rules and less restrictions and for most of the ensuing two years, Council remained split 4-3 on the issue. But more renters and affordable housing advocates started to press back, especially as the industry boomed into one of the biggest in the region, further taxing the already-strained housing supply.

Last year’s elections saw industry advocates fare badly while those favoring restrictions won out. The issue was hotly debated, and under the resulting pressure Council banned short-term rentals in the RAD and along Haywood Road in the last months of 2017. Pushed to come up with clearer information on the impacts of the often-shadowy industry, city staff finally delved into the extent of short-term rentals in areas where they were actually legal. They found that downtown developments were switching from housing to short-term rentals at a rapidly-increasing rate.

That provided a key rallying point for an ad-hoc alliance of left-leaning city residents and some centrists, both set on reining in the industry for very different reasons even as realtors and pro-Airbnb gentry tried to stop them. A nearly-citywide ban on whole home/apartment Airbnbs, mulled for years but never seriously acted upon, finally made its way rapidly through city government, passing committee after committee and heading to the new Council as its first serious controversy.

On Jan. 9, it landed on the dais.

‘The shape of things to come’

The fight over Airbnb is as complicated as a jargon-laden development policy, and as brutally simple as an eviction notice. It was clear from the start that there were a few wrinkles to the ban.

For one, North Carolina law makes it legally complicated (though not impossible) to force current, legal short-term rentals to cease. So if they notified the city (many, according to staff, didn’t) and if they operate in an area (mainly downtown) where they were legal, they won’t have to shut down under the new law. They would have to get a permit every year, and if they ever let it lapse they’d have to convert to housing or commercial space, but they could keep operating a whole home/apartment Airbnb even if it shifted to a new owner. Right now there are 67 such units, but between mid-December and Jan. 9, according to city staff, 53 more had applied to become short-term rentals.

Nonetheless, the new ban would shut the door on future whole home/apartment Airbnbs in a time where they were rapidly escalating in the areas where they were allowed.

This was a little hard to ascertain going into the hearing, as city staff’s framing of the issue was clear as mud in the agenda documents, laden in jargon to the degree of being difficult to parse for even experienced Council journalists. Staff refused to answer questions, claiming that new city policy forbids them from directly talking with the press.

Indeed, after a presentation that barely clarified things, Council member Vijay Kapoor specifically pressed head planner Shannon Tuch about what the new rules actually did.

“I think a lot of folks are wondering what this does about whole home short-term rentals downtown,” he said.

“If Council were to adopt this amendment as proposed the option to convert a dwelling unit to a short-term rental downtown would no longer be an option by right,” Tuch replied.

“Is there anywhere else in the city where you can do a whole home short-term rental by right?” Kapoor continued.

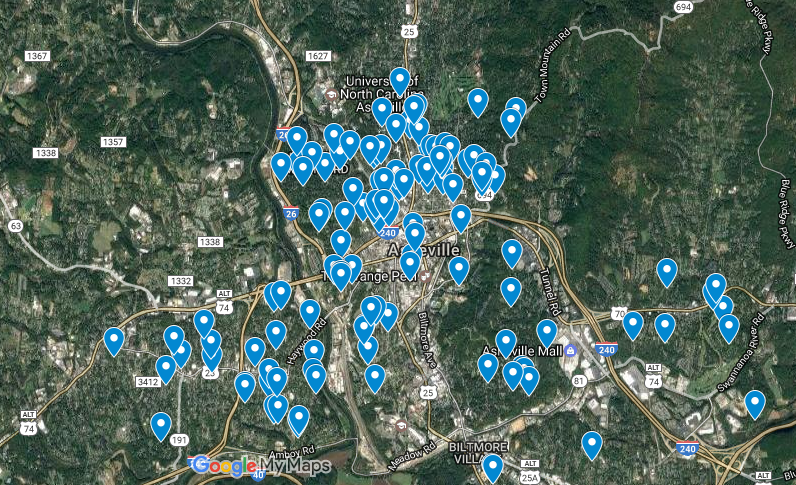

A snapshot from a map created as part of a 2016 Blade investigation, revealing part of the spread of illegal whole home/apartment throughout the city’s neighborhoods.

Tuch clarified that it would still be allowed in the resort district (areas right around the Grove Park Inn, Crowne Plaza and Richmond Hill). Going forward, anyone wanting to do a short-term rental would need to specifically request an exception to the ban from Council (as the elected officials can grant from most zoning rules).

With that, it was the public’s turn to duel. Local resident Moira Goree started off by reminding Council of the harsh cost the Airbnb industry had inflicted on locals like her.

“I’ve lived here my whole life, in the last year I moved five times,” she said. While the first time had been due to a changing roommate situation the “second time that house was sold out from under me to become a whole home short-term rental, the third time also sold out from under me, to become a whole home rental.”

The fourth time the only place she could find was as the “live-in cleaner” at a whole-home Airbnb where she was allowed to stay in the house only “about two nights a week” when visitors weren’t there.

“I was basically living in my car,” Goree said. Now, she finally lived in a place that likely wouldn’t become a whole home Airbnb, “because it has a hole in the floor and the roof leaks.”

“I think that’s the shape of things to come as far as whole home rentals pushing me, as an artist and local, pushing me out of town,” she continued.

Resident Eliza Alvarado admitted that she didn’t “have a lot of facts or figures” but she felt that Council shouldn’t ban homestays (which the proposed rules didn’t).

“I’ve lived downtown for over 10 years,” Kirk Adcock said. “It’s a much different place than it was when I moved in. There was still a sense of community, there were people I would meet on the street, there were still artists living downtown.”

But in the time since, he claimed, the city, chamber of commerce and the Tourism Development Authority had so heavily marketed Asheville to tourists that it had lost its local charm and prices had skyrocketed.

He wasn’t here to seek to reverse or check that tragic displacement. Instead the key question for Adcock, a longtime land developer and realtor, was: where’s my cut?

“You’re telling people that have paid high taxes, that are sick of walking over buskers and bums that we have to sell our place,” Adcock said. “Can we not rent [to tourists]? Why is it only the hotel lobby gets to rent?”

“It is a myth that any of this is about affordable housing downtown,” he continued. “Let’s get over the fact that [downtown] is different forever. It’s not a living place anymore, it’s a place for tourists and the wealthy.”

Angie Rainey asserted that her family owned a duplex near downtown, on Merrimon Avenue, and relied on renting out one of the whole apartments to tourists to make ends meet and enable their sustainable lifestyle.

“We bike or take a bus to church, the park and grocery stores,” she said. “As you know, the price for property in that particular neighborhood is fairly high. The only way for us to afford our mortgage is for us to live in a duplex and get income from the other half of the property.”

According to Buncombe County property records, however, ownership of the duplex was transferred to Rainey and her husband for free last year by a trust owned by his parents.

But Rainey claimed that renters, in one of the tightest housing markets in the Southeast, weren’t interested in an apartment near downtown. Instead, she said, they had no choice but to turn the living space into “a very suitable short-term rental for visitors to Asheville to benefit from a walkable getaway. Please do not deny middle-class families like ours the opportunity to directly benefit from Asheville’s tourism trade enough to allow us to pursue a healthy, environmentally sustainable lifestyle.”

The neighborhood where Rainey’s duplex is located was unaffected by the rules Council was debating on Jan. 9 — whole home/apartment short-term rentals have always been illegal there. Rainey added that her family managed multiple affordable housing properties but then claimed that were only affordable they were offset by the profits from their short-term rental. She also felt allowing whole home/apartment short-term rentals “empowered” women like her (who own multiple housing units).

Sue Robbins, representing Downtown Asheville Residential Neighbors, asserted that the group was squarely behind the new rules to stem the loss of housing in downtown.

Downtown business owner Casey Campfield called the vote “very encouraging” and asserted that landlords who wanted to make money from housing units could rent them out to locals instead of tourists.

“The needs for homes among cash-strapped renters is greater than the needs of multiple property owners and corporations for greater profits,” he said. “With a severe housing shortage and over 10 million visitors each year to a city of 90,000 residents there is simply no good argument for expanding tourist housing at the expense of local housing.”

A mix of locals and tourists, he said, would also help diversify the economy and buffer local businesses. But he added that more is needed, including making sure multiple property owners weren’t using the homestay rules as a way to enrich themselves.

“Multiple property owners already have a way to enrich themselves. It’s called renting to tenants.”

He also asked any member of Council operating a short-term rental “here or elsewhere” to disclose it. None replied.

Local musician and former Council candidate Andrew Fletcher noted he and his band had lost their practice space on Chicken Alley when the area was converted to short-term rentals, and that he saw the danger for renters like him growing.

“It affects the people who are most vulnerable, who make this city what it is: artists, musicians, people who bus your tables, serve your drinks, cook your food,” Fletcher said. “The people that are getting displaced aren’t being displaced by 120 unit hotels, they’re getting displaced by 120 individual Airbnb units scattered throughout the city.”

When he was a Council candidate, Fletcher noted he talked to many people who had been kicked out of town, “who don’t have mortgages they have landlords, and many of them told me the same story Moira [Goree] said. One day they go to put their rent check in the mailbox on time and they get an eviction letter out.”

“It needs to stop, if we care about the character of this community rather than the marginal profits of people who aren’t worried about where their next meal comes from.”

Andy Brokmeyer, who owns a wedding chapel that markets to visitors, was concerned that restricting whole home/apartment Airbnbs would damage ‘the beautiful menu for tourists who come here” and “limits their Asheville experience.”

“This issue is pushing way too fast,” he said. “I would ask Council to slow it down, work through this a little more clearly.”

Instead, he wanted “creative thinking” like an affordable housing fee on legal short-term rentals. He didn’t think those funds should go to affordable housing in the core of the city, as “I don’t see it being a reasonable thing for downtown anymore but maybe it could be supported elsewhere.”

‘For people who live here’

‘Just have a shortage of housing:’ Council member Julie Mayfield, a vocal supporter of the new Airbnb restrictions. File photo by Max Cooper.

Council member Julie Mayfield pushed the measure forward, asserting it would help halt the loss of the housing stock.

“We’ve talked in this room many, many times about the shortage of housing that we have in Asheville,” Mayfield said. “We have an extreme shortage of affordable housing, but we also just have a shortage of housing.”

“It’s a tried and true long-term strategy that if you have a shortage of housing you just need to build housing and that does serve, ultimately, to increase the affordability of older apartment buildings and older housing,” she continued. “Even by building $400,000 condos downtown,” she said, they were helping to expand the overall housing supply and taking some of the pressure off older units, at least “stemming the tide of lost housing.”

“If you are building a unit that someone can live in, it has a bedroom, a bathroom, a kitchen, we want that to be used for someone to live in long-term,” she said. “Hotels are not built to be lived in. They are different things.” She even put in a good word for some hoteliers, asserting that more of them than people thought “are owned by people who live here, they do invest in the community.”

“We are trying to keep downtown a place that has a good mix, that’s for people who live here, not just people who visit here,” Mayfield concluded. “That’s incredibly important to Asheville.”

Council member Keith Young, a frequent opponent of tighter regulation on the industry, asserting his remarks would be “all over the place.”

First, he claimed that the move had come too quickly, and he wanted instead a “comprehensive conversation” about Airbnbs throughout the city.

“This process moved so quickly we’ve seemed to omit a lot of that,” Young claimed. “Government never ceases to amaze me. I’ve been trying to get a gun buyback program for years and this moves forward in, what, five weeks?”

He claimed that now people looking to get a whole home/apartment Airbnb would have to come directly to Council for approval and given the current political make-up “I don’t think you’ll get it.”

‘I don’t think there’s an actual shortage of housing:’ Council member Keith Young downplayed the housing shortage while asserting a hodge-podge of reasons he opposed reining in whole home/apartment Airbnbs. File photo by Max Cooper.

“Property rights, someone came up here and mentioned something that seemed to fall in the line of property rights, I don’t know, but I like to think these would be things we would consider,” he continued.

He then veered into claiming “if you have about $300,000 I don’t think there’s a shortage of housing in Asheville. Now I know there’s a shortage of affordable housing. This isn’t about affordable housing, as stated. But I don’t think there’s an actual shortage of housing. You can go on Zillow and if you have $300,000 you can find somewhere to live in about all corridors of the city.”

According to the detailed 2015 Bowen report on Asheville’s housing crisis, the city’s shortage of available living units is so severe anyone making $75,000 or less a year faces considerable difficulty finding housing they can afford.

“Are we just going to ban all STRs in the city of Asheville?” Young continued. “It’s just one of those things, I’m very disappointed in how this process moved forward.”

But Kapoor defended the measure, noting that Council could still take a look at other aspects of the Airbnb issue, but needed to move quickly to halt the profusion of “mini-hotels” and make rules consistent throughout the city.

“I don’t think this was an easy thing to do, I think the speed with which we moved on this was important,” Kapoor continued. “The data indicating what was happening downtown, with the number of units that were being converted, was worth moving this process fast.”

Nonetheless, he added that several city committees had weighed in on the issue and it had received coverage in the media.

With that, the ban on whole home/apartment Airbnbs passed 6-1, with only Young against.

While the Airbnb fights will certainly continue, the vote made it crystal clear that the new Council, after facing considerable public pressure, is far more skeptical than the old on the arguments made by Airbnb industry supporters. Sometimes, the city’s political terrain does shift, and it shifts fast.

—

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by our readers. If you like what we do, donate directly to us on Patreon or make a one-time gift to support our work. Questions? Comments? Email us.