City Attorney Robin Currin’s far-right legal views have played a key role in halting progressive change. Now she’s resigning. A look at the damage she did, and what might happen next

Above: Asheville City Attorney Robin Currin, file photo by Max Cooper

The announcement came last Thursday morning. The email didn’t even have a subject line revealing its content, and the text read simply:

Robin Currin, Asheville City Attorney, has resigned, effective September 27, 2018. Ms. Currin will be assuming the role of City Attorney for Raleigh, NC.

“While we are disappointed to be losing Robin, her role in Raleigh is a wonderful career opportunity. It will also allow her to return to her long-time home. We will miss her leadership, skills and professionalism.” said Asheville Mayor, Esther Manheimer. “The City Council wishes her the very best.”

The Asheville City Attorney reports directly to the City Council. The City Council will begin the search for Ms Currin’s successor as soon as practicable.

Well, that changes things.

Since early 2014, when she was sworn in during a low-key ceremony in a City Hall conference room, Currin has proven a major influence on city policy, specifically hauling it in an extremely conservative direction. While the city attorney is one of the three positions that directly serves at the pleasure of Asheville City Council, the support of then-City manager Gary Jackson certainly helped her secure the job, and the two’s political outlooks were pretty closely aligned. Currin also had some key allies among “progressive” elected officials as well, for reasons we’ll delve into later in this piece.

But Currin would outdo even her managerial counterpart when it came to contempt for the public, scaling back transparency and creating the most hostile city attorney’s office in memory. She also proved to have a definite agenda of her own, pushing far-right legal views that would, for the next four years, see ostensibly progressive city government take some surprising positions. In areas from LGBT rights to housing to policing and open government, Currin’s office frequently combined with Jackson’s administration to form a de facto veto on ideas that tried to directly address injustice or check the powerful during a time of massive gentrification.

But times change. Under increasing pressure from a more left-leaning electorate (and even some centrists) tired of the city’s legal office serving as a giant “NO” stamp for every new idea, Currin had attracted an unusual amount of criticism for a job that often stays out of the limelight. With Jackson’s removal in March and the city potentially facing a wave of lawsuits around police brutality and other equity issues, she was in a more vulnerable political position than before. Currin was notoriously silent even for our notoriously opaque City Hall, but it’s not hard to see why a job offer for a powerful spot in Raleigh looked pretty appealing.

Combined with Jackson’s removal opening up the city manager job, the coming months offer a unique opportunity for the people of Asheville, as this Council will choose two of the most powerful positions in city government. Those choices will shape Asheville for the next decade.

That’s more important than ever because while there are city officials whose impact is hard to judge, Currin isn’t one of them. Her tenure was a disaster. There will no doubt be plenty of gentry bonhomie from some of our elected officials as the weeks wind on to her departure. But Currin deserves not a single word of respect or thanks, because she earned neither. All she did was make city government even less accountable to the people, hurt marginalized communities further and block even mildly progressive reforms.

That should not be forgiven, and we’ll be dealing with the impacts of that damage for years to come. Here’s a look at what that wreckage looks like, why Currin was able to inflict so much of it and what it reveals about how our city has to change.

The lost years

Currin’s background is as a land use and development attorney, practicing for many years in Raleigh before she was tapped to take Asheville’s top legal job.

She took over for longtime City Attorney Bob Oast, who retired from the post in mid-2013 after 16 years. While in office Oast was mostly a mild-mannered political moderate. Though he carried out plenty of controversial Council policies — and deserved plenty of his own share of criticism — he would actually rein in the city bureaucracy on occasion, especially on transparency issues. For example, in 2008 while I was investigating housing conditions for a Mountain Xpress story, some city staff tried to claim that landlord-tenant complaints weren’t public record. This position was completely illegal, and Oast quickly directed the staffers to cut the crud and turn over the documents, which they did.

That didn’t mean Oast didn’t defend some of the city’s questionable stances (post-retirement, he’s often taken jobs defending the hotel industry) or take a fairly cautious approach to policy (attorneys usually do), but compared to his successor he took transparency far more seriously and tended to take a less aggressive attitude towards pushing conservative policies. Importantly, he was one of the major city officials independent of the city manager, as Oast answered directly to Council and was already firmly entrenched in his office by the time Jackson was hired in 2005.

Currin proved very different; if city staff and Council were looking for an attorney whose outlooks was aligned closely with Jackson’s, they got it. Some of her influence first showed later in 2014, in the city’s bizarre campaign to crush the local busking scene. Her city legal department, working with some officers within the APD, started quietly broaching a bunch of ludicrously draconian restrictions, from background checking performers to banning them from having dogs. They pursued a similar course for almost three years, proposing various harsh measures and claiming that a thriving cultural scene beloved by most Ashevillians was a public safety problem.

This set the tone of many of Currin’s efforts: an unpopular far-right proposal prioritizing the wishes of the powerful (a smattering of gentry who felt buskers didn’t belong in public space) over working Ashevillians’ rights while taking dubious legal positions (busking has broad protections under the First Amendment) and showing outright contempt for members of the public. It also demonstrated the prominent role of Assistant City Attorney John Maddux (who’s still with the city and may replace Currin) as the point person for many of the most far-right positions Currin’s office would take, especially on policing.

The busking fight also revealed that, under Currin, the legal department would absolutely refuse to talk to press or the public. This isn’t standard practice. Under Oast, city attorneys would usually speak about their legal rationales for a given step. While there are real constraints on their profession, and there were some questions they admitted they couldn’t answer, it at least offered the public some insight into how a key city department functioned. Under Currin the office went completely silent.

In the busking battles Currin was eventually checked by a massive public backlash, busker organizing and the fact that despite her office’s belligerent stance, the performers stood a pretty good chance of getting most of the city’s proposals thrown out in court. Nonetheless, the issue dragged on for years, eating up city resources in pursuit of what amounted to a petty grudge by a small group of people towards a key part of Asheville’s culture.

It didn’t stop there. In late 2014, local activists cited a legal white paper from the progressive N.C. Justice Center to assert that the city should try to pass its own minimum wage to better address Asheville’s infamously low pay. Currin came out strongly against a step. This too would set a theme. Currin has repeatedly asserted that local government has little or no power to regulate business, despite a slew of state court cases showing that — with some limitations — they do. In other cases, Currin would even claim Asheville couldn’t legally take steps already taken by other N.C. cities. Currin’s opposition gave Council the cover to refuse to even study the wage issue.

Then, in early 2016, came a major incident that made it clear Currin wasn’t just an especially cautious lawyer but working from a very specific worldview, came in early 2016. At Council’s retreat, she objected to including the they/them pronouns used by many trans and non-binary people in a city policy document, claiming it would be “incorrect.” Witnessing it at the time, I thought it was a case of either stunning ignorance or outright bigotry.

What happened next revealed that it was just bigotry. A few months later, after Charlotte passed a non-discrimination ordinance, multiple state and local LGBT rights groups called on Asheville to do the same.

The step would have made sense and would have provided key momentum for such protections (facing multiple cities is a lot harder than facing one). Indeed, Asheville City Council had repeatedly touted their pro-LGBT credentials. The year before, City Hall had even flown a pride flag after a federal judge legalized equal marriage in North Carolina. But Currin told Council that despite Charlotte taking such a step, Asheville legally couldn’t do so.

The initial rationale cited by Currin wasn’t just dubious this time, it was nonsensical. Currin maintained that basic non-discrimination protections were illegal under state law. She asserted this counter to extensively-researched legal basis for the step provided by the Charlotte city attorney’s office (not exactly known for their radical views).

To make it clear exactly how extreme her position was, even the N.C. General Assembly mostly didn’t hold it, claiming that they had to convene and pass an entirely new law to counter Charlotte’s ordinance. Currin’s legal view was only shared by the most fanatical right-wing legislators.

It foreshadowed what was to come. The damage continued after HB2, when Council had opportunities to forge ahead anyway and directly challenge the law by passing their own non-discrimination ordinance. Indeed, that September LGBT groups pushed them do so again, laying out the legal rationale and even offered the assistance a free legal team specifically trained in the issue.

Vetoed: Pro-trans rights protesters rallying against HB2 Pack Square in 2016. Currin’s legal department played a key role in ensuring the city didn’t fight HB2 or pursue non-discrimination protections. Photo by Max Cooper.

At each step of the way, it was Currin’s legal department that made sure these proposals didn’t advance. Their rationale was even influential on some of Council’s more dissident members. Contra reams of legal research from just about every progressive group out there, then-Council member Cecil Bothwell espoused hook, line and sinker Currin’s assertions that any challenge to HB2 had no chance in court.

At a time when LGBT Ashevillians were under particular threat, the city completely abandoned them and Currin — someone who had publicly demonstrated a bigoted streak — was a major reason why.

That wasn’t the only issue where Currin’s influence proved particularly damaging. At a time when Asheville’s housing crisis reached nationally-bad proportions, she played a major role in scuttling attempts to make a key reform. As the housing crisis worsened further in 2015 and 2016, the idea of passing inclusionary zoning — a requirement that all new developments either have a certain percentage of affordable units or pay into a city fund to build housing — gained momentum.

This step had especially solid legal footing. Both Chapel Hill and Davidson had already adopted it, and Chapel Hill’s ordinance has now been on the books for most of a decade. While not a panacea, it is one step where cities can use their considerable powers over development to try to ensure more affordability. Importantly, it also had grassroots support throughout the city. At the very least, it looked like the idea would get some serious research that might come up with a variety of options to strengthen the city’s affordable housing response.

But Currin was strongly against the idea, and her department’s opposition stopped city committees from even researching it. In this case their legal rationale was especially shaky, given that two other N.C. cities had successfully had such an ordinance on the books for years. But it worked, and inclusionary zoning died.

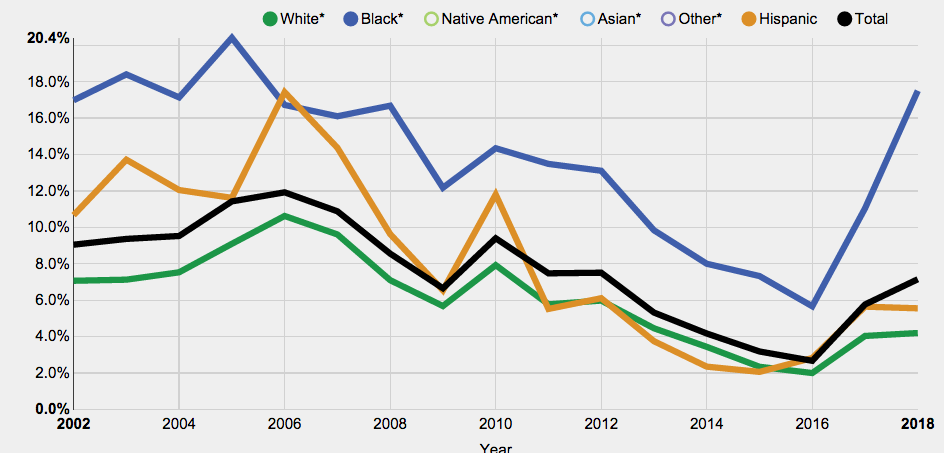

Search and seizure: APD stats showing the search rates for drivers by race and ethnicity. As Currin’s legal department blocked NAACP policing reforms, Asheville’s disparities grew to the worst of any major city in the state. Chart from Open Data Policing.

Last year Currin’s department, working hand-in-hand with APD Chief Tammy Hooper, also played a key role in halting police reforms proposed by the local NAACP and extensively researched by attorneys at the Southern Coalition for Social Justice. In these cases, the city’s legal rationales (pushed by Maddux) for rejecting the reforms basically boiled down to “other cities don’t do it so why should we.” This year, under massive public pressure, Council finally passed the reforms. By that time, Asheville had the worst racial traffic stop disparities of any major city in the state.

Worsening all these issues was Currin’s absolutely opposition to even basic transparency, which the Blade delved into extensively in 2016. Her department claimed APD recordings of peaceful protests were “criminal investigative records” (even though they admitted no crime had been committed) and declared them closed (for which they got sued). They likewise claimed that records of publicly-held Civil Service Board hearings also weren’t public record, nor was body camera footage (even before state law clamped down on public access).

Currin’s steps weren’t just damaging, they came at the worst possible time on almost every front. Rather than working with local artists and musicians, the city wasted years trying to drive them out. The refusal to move on LGBT rights weakened the fight against HB2 at a key time. The veto on even considering the minimum wage proposal steered the city away from policy on a key issue even as many Ashevillians’ pay situation worsened. The lack of inclusionary zoning (or even researching similar options) deprived the city of key tools to address housing while that crisis became a catastrophe. Currin’s “we’re not doing anything ever” attitude on police reform enabled a department that now has the worst racial disparities in the state and has made national headlines for incidents of racist violence.

That last one may have finally put the most pressure on her office, as Maddux and the legal department apparently knew about the horrific APD attack on Johnnie Rush last August, even as Council remained unaware until this year. The city is almost certainly going to end up in court over that and other policing issues, promising to completely tank the city attorney’s already-low reputation among most of the public. She cinched a move to Raleigh before the situation got worse.

The coup de grace, Currin’s hostility to even basic transparency further damaged public trust during all these crises.

That was Currin’s “leadership,” and thanks to it, Asheville didn’t just lose opportunities thanks to her influence, we lost whole years. With the exception of Jackson, it’s hard to think of another city official who so determinedly made things so much worse in so many areas.

Currin’s defenders have typically pointed to the fact that under her direction the city maintained control of its water system against an effort by state legislators to seize it. This doesn’t (pardon the pun) hold water. Due to how obscenely over-reaching the state bill was, the city was on solid ground with the water lawsuit long before Currin took office. The result would have been no different with Oast or any other basically-competent attorney in the role. Surely, Council could have found someone else who would have won a similar victory without making every other problem worse in the process.

A convenient smokescreen

But another question looms large over this. As much as we should hold officials like Currin accountable, we should also turn our attention to the people that put them there. How did supposedly “progressive” city leaders keep listening to such far-right views and letting them shape policy at so many key moments?

Like with Jackson’s long tenure, part of it was that their identities and privileges lined up pretty nicely, and elected officials are always less likely to rein in officials they appoint when that’s the case. Manheimer, like Currin, is a well-off attorney (Currin pulled in over $170,000 a year in her job) focusing on land use and development. Vice Mayor Gwen Wisler was a CEO of a major company before retiring to Asheville, a background far more likely to hire a pro-corporate attorney than defend against one. Council member Julie Mayfield, also a lawyer, has a background in environmental activism but is a centrist who’s repeatedly spoken dismissively about local civil rights activists and has frequently focused on encouraging the city to more closely ally with Duke Energy, a company that’s literally the villain in countless union songs.

Of Council members with legal backgrounds, none were the social justice types that might have used their expertise and ethics to counter Currin. Throughout her tenure most of the elected officials overseeing her were, like her, white, well-off and insulated from the damage of gentrification. They were primed to give her the benefit of the doubt, and they did.

There was another reason too. One of the most damaging aspects of Currin’s tenure was what it prevented: on multiple key issues the public didn’t get the full hearing and up-or-down vote we deserved. Her legal department didn’t just stop specific proposals; they effectively shut down vital discussion in whole policy areas.

While city attorney is always a powerful position, Currin took an unusually outsized role because of the aggressiveness she displayed in pursuing her views, and how out-of-synch they were with the vast majority of the city.

For some on Council, this was a feature, not a bug, because it made sure that reforms didn’t reach the dais, where they would inconveniently have to cast a vote.

That meant a lot, especially to centrists like Manheimer who were especially closely allied with Currin. Put to an outright vote, measures like fighting HB2 or reforming the police department would face fairly good odds. The ideas are widely popular with Asheville’s people, and the ensuing public pressure would make it really hard for elected officials to publicly refuse. They wanted to avoid exactly what’s finally started happening in the past few months with measures like the NAACP reforms; public pressure forcing a vote on social justice stances many of them are reluctant to take.

So “legal says we can’t” became a useful excuse allowing local politicians and city staff to avoid having to even consider ideas a lot of them were lukewarm on anyway, while usually avoiding a backlash.

In some ways, that’s the most important part of this story; Currin’s damage wasn’t wrought by her alone. At every step of the way it was enabled by elected officials and other key city staff. Some of them enabled this simply by a lack of courage, unable to muster even a “we have heard your concerns but we make the final decision” in response to some of her more absurd stances.

But others did so because at the end of the day they don’t view LGBT rights, fair pay, affordable housing, transparency and police reforms as important priorities. Their views are a lot closer to Currin’s than they are to most of the people of this city and Asheville’s working just fine for them.

So because of cowardice and convenience, we’re left with an imbalance of power, one where Council’s answered to the city attorney far more often than the other way around.

The next city attorney, the next city manager, need to at the very least have some level of actual alignment with the people of the city. But far more importantly, Council needs to be reminded that at the end of the day both these positions exist to serve us — and their occupants should be promptly removed when they don’t. At the core of Currin’s crusade was the treatment of most Ashevillians as an expendable nuisance. To repair the damage she’s done will require a Council that treats rich lawyers as the disposable ones.

—

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by our readers. If you like what we do, donate directly to us on Patreon or make a one-time gift to support our work. Questions? Comments? Email us.