Major racial disparities in traffic stops and questions about police reporting, building for months, finally take center stage as Council dubs the situation an ’emergency’

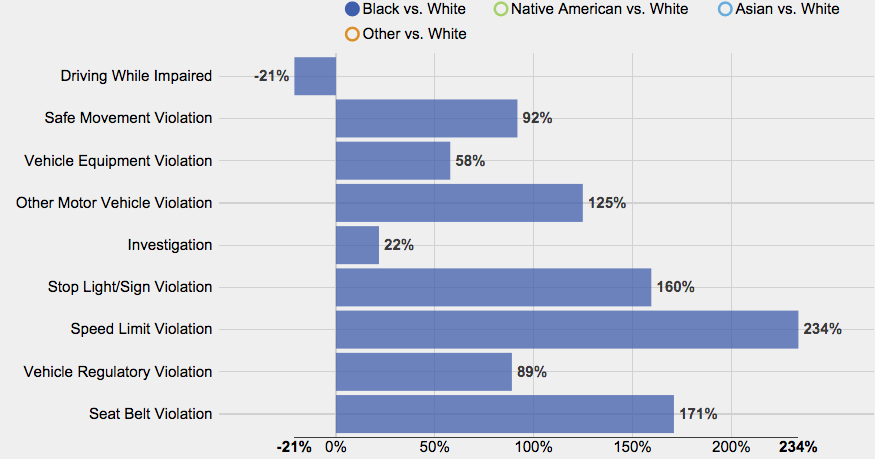

Above: A chart from Open Data Policing‘s analysis of the Asheville Police Department, showing that black drivers are far more likely than white drivers to be searched for the same offenses.

Every month police departments throughout the state send off traffic stop and search numbers to the State Bureau of Investigation. This is required by state law, and the numbers provide a picture of who’s stopped, for what, and if they’re searched.

However, while the numbers are public record, comparing and visualizing them over time can be challenging. So in late 2015 the Southern Coalition for Social Justice, a Durham-based civil rights group, started the Open Data Policing project, gathering this information on a single site and offering multiple ways to delve into and visualize it.

The numbers for Asheville showed that the APD, like agencies around the state and country, pulled over and searched black drivers disproportionately more often than white ones. This is despite the fact that white drivers in Asheville are slightly more likely to actually have contraband.

Those numbers became a touchstone of local discussion in 2016, as activists referred to them after the reactions surrounding Sgt. Tyler Radford’s killing of Jerry Williams last July. The Blade also repeatedly highlighted those numbers in our coverage at the time, partly to show how long-running problems and disparities played a role in the community reaction to Williams’ killing and the skepticism that greeted the official response.

Last year, local NAACP and open government activists contacted the SCSJ in an effort to use the data to both highlight a serious problem and propose some solutions. Besides the disparities, they had further concerns as well: an unusually high number of APD searches claimed that the driver had consented, rather than that the officer had probable cause or a warrant. A high number of consent searches can indicate that officers are relying on hunches or biases rather than evidence, and black drivers are under significantly more pressure to agree to them, fuelling disparities.

There was also a sudden decline in reported traffic stops around 2010 that could indicate that some stops were not being reported to the SBI as required.

These concerns were first brought to the attention of top APD officials last November. Early this year, the NAACP held a public presentation by SCSJ attorney Ian Mance, with the groups involved calling for three reforms all adopted to one degree or another by some other police departments in N.C. On Feb. 1 Mance made a similar presentation to the city’s police committee. On Feb. 27 the NAACP’s Dee Williams called on Council’s Public Safety Committee to send the matter up the chain and APD Chief Tammy Hooper promised she was studying the issue.

But there wasn’t much movement over the coming months, or any official response from the APD even as public discussion of the issue mounted. On April 25, however, the matter finally landed on Council’s doorstep and the elected officials found, after some debate and pushback, a sense of urgency.

The issue delves into some serious tensions in what remains a deeply segregated city. Issues with racial disparities in policing go back decades, but have seen increased attention over the past few years due to increasing activism, the controversy over Williams’ killing, several high profile use of force incidents and multiple controversies over Chief Tammy Hooper’s leadership. This has increased over recent months, partly due to the backlash to Hooper’s controversial $1 million proposal to ramp up policing downtown.

There was also notable tension on the Council dais during some of the discussions, as some members sought to send it back to committee and others wanted it addressed more quickly by the elected officials themselves, because “driving while black in Asheville is real” as Council member Keith Young put it. Mayor Esther Manheimer even dubbed the situation “an emergency,” though unlike Young she initially favored bouncing the issue back down the chain, possibly until June.

The two weeks following the meeting have seen the APD’s official response take issue with the assertion that there was a widespread under-reporting of stops or that consent searches were over-used in recent years. But it also looks like months of political pressure might have had some effect: the APD claims that they’ll implement one of the reforms sought by activists. If Council will force them to adopt the rest remains to be seen, but they take up the issue again tonight, May 9.

The long and winding road

The path from data on a page to Council emergency began last year. Local advocate Dee Williams was one of the leaders of the successful effort to “ban the box” automatically asking about a criminal conviction for city or county jobs. As that effort continued, community members kept bringing up racial disparities in APD traffic stops as another major problem the city needed to face.

“We started talking to people about how much they were stopped,” Williams recalls, and started working with other locals as the chair of the local NAACP’s Criminal Justice Reform committee. From there, attention turned to the data as one of the ways to deal with “a lot of resistance, based on what I know about the history of how police departments operate.”

She’d found data persuasive in previous efforts, including around minority contracting with the city, so Williams, who earlier this year declared as a Council candidate with the backing of the Green Party, started working with local open government advocates.

“When data demonstrated disparities, it took some of the passion out of it, showed where the problems were, maybe even some solutions to those, rather than attacking individuals,” she tells the Blade. “So let’s try to find some data.”

They sought out the SCSJ. Williams and other Ban the Box activists had previously worked with the group on that effort. The civil rights group, especially Mance, were also behind the Open Data Policing effort.

However, as they started pushing forward in 2016 and early this year, Williams claimed the coalition encountered resistance from city officials.

“There’s not a lot of receptivity, at least from the officials I’ve seen,” she says. “They’re not used to citizens presenting findings to them and asking for feedback and to take action. It’s almost like they think if a policy doesn’t come from the top down, it’s no good. It’s the exact opposite of the way a democracy should work.”

“I’ve seen it be very closed, it’s almost like they want to say it’s wrong before they even take a look at it,” she continues. “You’d think they would want to examine it before now. It’s data, there’s tools there for the chief and others to use. If you want to know how your department’s doing, plug it in.”

By the time he started traveling to Asheville in his role as “a resource for community groups, police chiefs or lawyers that want to work to this data” the site’s information had played a role in policy changes in Greensboro, Fayetteville, Chapel Hill and other law enforcement agencies throughout the state, Mance recalls.

“What we see in Asheville is consistent with what we see in cities of its size and in larger cities,” Mance says, though he notes that could change if more stops are reported. The two areas Asheville did stand out in, he noted repeatedly, were the possibility that traffic stop numbers were being under-reported and the unusually high number of consent searches.

“Generally consent searches happen when officers don’t have probable cause, they’re relying more on hunches than acting on evidence, facts and circumstances,” Mance said. “It raises the question if searches are more rooted in legitimate law enforcement need or if it’s just the officer’s gut instinct. Given what we know about implicit bias, that can be problematic. That’s why we have these hard and fast rules for when you can and can’t search someone.”

“It’s not like they have a super high seizure rate, so most of the people [the APD are] searching are innocent,” Mance continues. “That’s something the department might need to reflect on.”

Mance and Williams had notified Hooper about the concerns about the possibility of unreported stops as early as last November.

To test if stops were actually going unreported, Mance and local open government advocates pulled a court calendar for late 2016 and early 2017, then extracted 50 cases of traffic infractions reported by the APD. The oldest citation they reviewed was issued in May, some of the most recent in January of this year.

They took those numbers to the clerk, pulled the files and compared the demographic information and details with those reported to the SBI’s database. They found that over half of the stops, 58 percent, didn’t show up in those reported to the SBI.

“I’m not saying 58 percent of all stops aren’t reported, I’m only speaking about the sample,” Mance emphasizes. “At previous meetings, the department asserted they seemed confident all stops were being reported [to the SBI]. So we just wanted to test that hypothesis. If that was true, they should all have shown up.”

The possibilities, he tells the Blade, are that some officers were consistently not reporting their stops, that there was some technical problem in transferring those reports to the APD or some combination of the two.

The public and police, Williams asserts, should find the possibility that traffic stop records regularly weren’t reported to the SBI troubling and the “sky high consent search” rate raises major questions about “what’s being verbalized” during traffic stops and “the culture of the Asheville Police Department. Is it a culture of us versus them?”

“Council is almost always confused when something comes up that’s controversial,” Williams emphasizes. “You have to be willing to work with people, but there’s a limit when it comes to moral authority or issues that impact public safety. There’s a certain amount of healthy skepticism, accountability and transparency that’s called for.”

‘It’s real, it’s alive’

On April 25 Mance presented his data in Asheville for the third time. He told Council about the background of Open Data Policing, and the result of the 50-citation audit indicating that the APD had some major issues with its stop data not reaching the SBI.

Then came the stop and search numbers.

“Over the last decade and a half black drivers have been stopped at a rate about 50 percent greater than their representation in the city population,” Mance said. “That number has gone to about 100 percent more in 2017. So far this year over 27 percent of all stops in Asheville have involved black drivers.”

“In searches, we also see significant over-representation” of black drivers, he continued. In the first two months of 2017 the disparities worsened, marking “the first time the department has reported searched more black motorists than white motorists, with black drivers accounting for 55 percent of all searches.”

“In all categories there is a significantly higher likelihood that the black driver will be searched,” though white drivers are found carrying contraband slightly more often. Indeed, across the state “we have very good data that black and white drivers are carrying contraband at essentially the same rate, though we do see black drivers searched more often.”

‘We’re fortunate in Asheville:’ Council member Julie Mayfield claimed that while racial disparities in stops are an issue throughout the country, she believes the APD’s leadership is willing to deal with them.

“But what does that mean for us?” Council member Julie Mayfield said. “I’m having trouble drawing a conclusion here.”

“Black drivers are searched more,” Young replied, and laughter broke out in the chambers (“I get that,” Mayfield then said).

Mance continued that Asheville’s consent search numbers were unusually high, 58 percent of all searches over the last five years. By comparison, he noted, only three percent of searches were consent searches in Fayetteville, 13 percent in Durham and 21 percent in Concord.

“That’s a high number,” he continued.

“Is that bad? Is that better or worse than probable cause?” Manheimer asked.

“I’ve had police chiefs tell me if that number creeps above 40 percent that they get concerned, that it might be indicative of fishing expeditions,” Mance replied.

The disparities continued when it came to regulatory and equipment stops (expired registration, broken tail light, etc.), as 40 percent of Asheville black drivers stopped were stopped for such reasons, as compared to 32 percent for white drivers.

“Over time that does contribute to these racial disparities,” he said.

He encouraged the city to “scrutinize and address the data reporting issue,” de-emphasize regulatory and equipment stops, require written consent for searches and to do periodic audits of individual officer’s traffic stop data “as an early warning system” of disparity issues something the Open Data Policing site makes easy for police chiefs. In cities around N.C., he said, these had resulted in declines in racial disparities.

“These seem reasonable responses,” Council member Gordon Smith said. “I’d be interested in the Public Safety Committee getting in the weeds on this stuff.”

“It would be helpful to give the police chief an opportunity to respond,” City Manager Gary Jackson said. “I think thoughtful consideration would be in order.”

“They look like fairly reasonable policies to me,” Council member Cecil Bothwell, chair of the Public Safety Committee, said, adding that the committee had heard a summary of the data and referred it up to Council.

‘Driving while black in Asheville is real:’ Council member Keith Young said Council needed to treat the issue of major racial disparities in traffic stops and searches as an urgent one.

Mayfield said such problems were an issue without the country, and took the opportunity to reaffirm her support for APD Chief Hooper.

“You’ve presented us some very challenging information,” Mayfield said. “My guess is if people dug into this data in many, many, many, many cities across the country, particularly in the South, we would find similar things. We’re fortunate in Asheville we have a police chief who’s indicated a willingness to tackle these kind of issues.”

“A city like Asheville can be on the forefront of moving forward.”

But Young asserted that Council needed to act with a bit more urgency than just referring the matter back to committee. He had major concerns about the lack of traffic stop reporting, and another issue.

“There’s a big ‘ol elephant sitting in the room that I don’t think has been addressed and glossed over a little bit, but I’m going to sit right on top of that elephant” Young said. “Driving while black in Asheville is real, based on the information you presented. It is real, it is alive. We’re more than 200 percent more likely to be stopped and searched, but contraband found is about equal. That says a lot.”

“Anecdotally I always thought driving while black was there, but the data you’ve presented has definitely shown there, so I’m waiting for a competent response,” he continued.

Manheimer thanked Mance and claimed Council was interested in the proposed reforms, but wanted to give Hooper “time to review the information and take a hard look at these recommendations.”

Young had problems with that approach, “I feel that Mr. Mance and his data has been through the committee system” and any APD response should come directly to Council. “I don’t think it should go back to a committee.”

Manheimer favored sending the issue back to committee to “have a more thorough conversation and take some public comment.”

“I think this is a great place for public comment,” Young replied.

“I’m not disagreeing with you, Keith,” Manheimer shot back. “Public comment is very important. I’m not trying to say that. I’m trying to make sure we have a process that is thorough and gives staff the opportunity to absorb this and figure out what we need to do as a city to make a difference.”

Mayfield wanted to give Hooper more time, bring the matter back before the Public Safety Committee and revisit it at Council a month or more later.

“I think this is going to be a long process, I don’t think we’re going to fix it in one Council meeting,” Manheimer said.

“I’m not suggesting fix it, but we heard this here, it would be good to have the information come back here,” Young said.

More back-and-forth followed, with Mayfield again asserting that a committee taking the issue up would make for an easier discussion. Young wasn’t convinced.

“I’ve heard this information at [the police committee], you’ve heard it an abbreviated version at public safety and we’ve heard it here, I feel like this is a punt…”

“We’re focusing on the solutions now,” Manheimer cut in.

“What we haven’t heard is the department’s response,” Mayfield added.

Bothwell noted that the issue could come back before Council to consider how the reforms would change the APD’s process, and the elected officials could opt to direct the reforms themselves. “It seems there are some clear policy proposals,” Young added.

Smith also inclined toward letting the issue go back before a committee, “I don’t see any harm in doing it.”

Jackson tried to schedule the next discussion of the issue for early June. But then Smith also suggested having some kind of response by the May 9 meeting, “with a note that if this is the rate this is happening at right now, there is an urgency to address these issues right now. With some policy pieces we have that luxury of time, but the people getting stopped and searched don’t.”

“But it won’t take two years like body cams,” Bothwell quipped, as Council agreed to focus on the issue at its next meeting.

‘You can’t just sweep it under the rug’

Things didn’t end there. During the open public comment period, Council member Brian Haynes noted he regretted not speaking up earlier and agreed with Young “that it should come back to us as soon as the chief is ready with her answers. Though this data was not surprising it was extremely disturbing, I don’t think we can let this go any longer than we should.”

Williams told Council that “I am grossly disappointed in the response. Anecdotally, we already knew there were some problems here.”

Despite the issues demonstrated by the data, she noted, the city was ready to throw $1 million behind expanding the force before it corrected its problems.

“We don’t want to be obstructionist and we certainly don’t want to continue to leave the area to get help and recognition for our problems, but we have no choice,” she said. “Folks heard your responses, it seemed like it’s being kicked down the road, so they left.”

So the NAACP and open government advocates were going to reach out to other groups, she said, and try to generate more pressure. “We don’t seem to be getting much help here.”

Patrick Conant of PRC Applications and a longtime open government advocate who helped Mance with the audit, emphasized “I am a bit frustrated, just hearing the discussion, that we’re talking about sending it back to another committee.”

After all, he continued, Hooper and the APD had heard the information multiple times since November, and it was presented to the public on several occasions before most of Council suddenly discovered a sense of urgency about the issue.

“We’ve been doing this for four, five months,” Conant said. “It took us an hour to see data was missing. Council needs to hold this process accountable. This is too important, you can’t just sweep it under the rug or wait a year, two years and see what happen. For some people these decisions are life or death.”

“One of the things we struggle with here is that we’re a Council-manager form of government,” Manheimer replied. “We’re not structurally set up to impose policies decisions directly on the police chief. ”

This is untrue. Council has the authority to set policies for all city departments, including the APD, as long as the rules they make don’t run afoul of federal or state law.

“So we have to work through our system of government,” Manheimer continued. “That sounds sort of bureaucratic and unsatisfying, especially when we’re dealing with an issue that is an emergency.”

“I think we’re unified here in trying to get us to a better place.”

The police response

Despite the long road through meetings with city staff, public presentations and multiple city committees, no senior city staff or APD leader was on hand to reply to the presentation or Council’s concerns on April 25.

But last Thursday the APD did release an official response, a seven page report that they’ll present at tonight’s Council meeting.

The report claims the department is ready to adopt one of the proposed reforms (auditing individual officers’ stop data). But it balks at the other two. The report claims the APD doesn’t emphasize citations for equipment violations (instead issuing a warning first) but won’t stop enforcing them. It also claims that the department doesn’t need to have a policy of written consent for searches because it can review body camera footage instead.

Their report also disagrees with some of Mance’s conclusions, especially around a widespread lack of reporting traffic stops to the SBI and the over-use of consent searches, but confirms others.

When it comes to consent searches, the report claims that they used to be far higher but have declined over the last few years:

In the period of 2010-2012, the number of consent searches actually exceeded the number of other searches, equating to approximately 59% of all searches. This represents an unusually high percentage of consent searches, for which Mr. Mance’s concerns are well taken. However, in the four years following, 2013-2016, the number of consent searches equate to about 39% of all searches. Looking only at the last two years, 2015-2016, consent searches equate to 34% of all searches. Still a high percentage, but continuing to trend downward.

There is no specific provable explanation for the reduction. Over the past several years, all APD officers have received training specific to implicit bias as well as other racial sensitivity training which may be a factor in the reduction. Further, since July 2015 APD has been steadily gaining momentum in incorporating 21st Century Policing practices with a focus on procedural justice and community engagement.

As for regulatory stops and their role in driving racial disparity, this is what the APD claims:

In his presentation, Mr. Mance stated that regulatory and equipment based traffic stops

disproportionately impact black motorists in Asheville and reported that an analysis of stops beginning in 2011 revealed that 40% of black motorists were stopped for these violations compared to 32% of white motorists. APD does not dispute these calculations. The reasons why drivers, regardless of race, chose to operate vehicles that are not properly registered, have defective equipment issues, or other regulatory concerns is debatable, but it stands to reason that a substantial portion of these violations are the result of the inability of people in lower income circumstances to afford to keep their vehicle in compliance with these laws. As such, these stops necessarily have a disparate impact on African

American drivers.

APD officers will not be prohibited from conducting lawfully permitted traffic stops for regulatory or equipment violations. At the same time, these violations are not, and have not been a priority for APD and will not be emphasized as such.

Notably, Mance’s reports and other comments made about the role of these stops in disparities note that it’s the stop itself that may result in disparity numbers, whether there’s a citation issued or not and that de-emphasizing such stops is an effort to reduce such encounters. The APD report does not address that issue.

The APD report also denies that there’s any widespread problem with failing to report traffic citations.

“Since July 2016, APD has conducted monthly compliance audits of traffic stop reports and at no time have such audits found any data whatsoever that is consistent with Mr. Mance’s assertion,” the report claims.

It claims that when Mance compared Asheville’s stop numbers to Concord, he didn’t account for that police department doing far more traffic enfrocement due to its unique position along major interstates.

However, in two months in 2015, the APD report also found that over 1,300 stop reports were, in fact, not sent to the SBI.

“The uploading of traffic stop data to the SBI database is an entirely automated process,” the report claims. “A disclaimer on its site explains that a small variance is not unusual, however, APD reported more than 1300 traffic stops in those two months that do not appear in their database. It is unclear why this occurred and there have been no subsequent similar anomalies.”

While the report notes that “the history of disparate and racist treatment of African Americans, including in our own community, must be acknowledged. Reports such as the one presented by Mr. Mance bring examples of this to light that can be specifically addressed and corrected” it only takes up one of the three reforms and claims that two of the major issues the reports have cited (under-reporting of traffic numbers and over-use of consent searches) aren’t major issues at all.

Importantly, the report also claims that Mance did not turn over the citations he’d audited when asked by the APD and quotes an email where Mance notes that the audit he performed did not necessarily indicate under-reporting for the whole department.

Pressing forward

Contacted by the Blade about the assertions in the report, Mance contradicts many of the APD’s claims about the audit of unreported traffic stops. He claimed he spoke with an APD official on April 26 for over an hour, the day after his report to Council, that he did send some of his citations on for review and even offered to do a joint audit with the APD to help figure out if the problem of un-reported traffic stops is more widespread.

“In fact I did send them citations,” Mance says. “I didn’t send them all of them. I was clear that I was a little frustrated with the chief’s decision to critique our method before we’d even really discussed what the method was. It felt like, talking to them the next day after she’d critiqued me in the paper, that they were looking to undermine what we were doing in some way, so I was a little dubious of their purposes.”

Instead, he notes, he sent some of the citations on “so you can see what I’m doing and check them. Then if you have a concern about what I’m doing, or a critique of what I’m doing, I’m available to talk about it. I offered to come to Asheville, to meet with them at APD and do an audit with them. They did not address the stops I did send them. I’ve since tried calling them a number of times to have a dialogue about this report and have not been able to reach them.”

“I’ve been very careful not to assert our sample is representative,” he said of the previous audit, but adds it’s clear there’s a problem the APD needs to deal with when it comes to not reporting its traffic stops. The email the APD quotes, he claims, was from a separate discussion from the disclosure of citations and is taken out-of-context.

“It does seem that they are acknowledging that there are over 1300 un-reported traffic stops in 2015, that seems to substantiate our assertion that some of the traffic stops are not being reported,” he said. If they want to, “the APD is well set-up to conduct an audit and get to the bottom of this.”

But he adds that since April 25, he’s contacted some of the people involved in the un-reported citations their audit found and, after discussing the stop with them, felt it was clear “at least some of these stops should have been reported.”

The issue might attract even more attention in the weeks to come. After all, in the first two months of 2017 the racial disparities in the APD’s reported stops were worse, not better. Mance notes that while only two months have been reported, the disparities are “the highest since Asheville started reporting data in 2002.”

“Those numbers may level out once we’re six months into the year, but it does seem the percentages have shifted in a worrying direction, though I would caution drawing too much from that.”

Williams claims she’s found Council’s response lacking, with city government as a whole unwilling to admit the scale of the problem.

“What bothers me when they see these numbers, they always ask for more information from the chief and the department,” and they treated the data like “alternative facts” rather than “the chief and Council admitting we have a problem,” adopting the reforms and seriously asking why a transparent, accountable police department wouldn’t have looked into these issues on their own long before now.

“Are you leading or are you being led?” Williams asks. “There has been a total breakdown of trust in the black community with the Asheville Police Department. That needs to be admitted and then we need to look for solutions.”

—

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by its readers. If you like what we do, donate directly to us on Patreon or make a one-time gift to support our work. Questions? Comments? Email us.