Tensions mount over a controversial push to expand policing, some shady numbers and paltry levels of funding for local social services as Council hashes out a budget

Above: Asheville Police Department Chief Tammy Hooper. File photo by Max Cooper.

For months tensions built. Normally sleepy committee meetings were packed with protesters. Jargon-laden budget hearings were pushed to a larger room because of public turnout. Instead of the usual question-and-answer presentations, there were closed door meetings. City officials, including some Council members, ended up on the receiving end of repeated criticism.

Asheville is in a time of tension. On fronts from segregated neighborhoods to rising rents it defines the lives of the tens of thousands who struggle to keep their heads above water in a gentrifying city. Many of the issues stretch back decades, but over the last years this reality has become particularly stark, leading to upsets in our local politics. The usual rules and routines increasingly falter against the forces of long-neglected issues, collapsing trust and dwindling public patience.

On April 11, those tensions again flared into the open. The main flashpoint, what had brought all those members of the public out for months, is a controversial push by Asheville Police Department Chief Tammy Hooper for $1 million a year to massively expand policing in the core of the city. She claims it’s necessary to deal with the challenges posed by a larger population in a busy tourist town, though some of the numbers she cites don’t seem to hold up under scrutiny or are lacking essential context.

But Hooper and the APD’s leadership are already under fire over racial disparities, use of force and a lack of transparency. So multiple groups and locals have pushed back against her proposal, wanting the funds put towards social services to deal with the impact of gentrification instead of something they believe will brutally increase it.

On April 11 one controversy in City Hall was over a potential excess of resources directed towards one institution, another emerged over a related issue: far too little going to others. The city has a pot of money to distribute to local non-profits, especially those helping out marginalized communities. But that pool of cash is tiny, currently less than Hooper’s annual salary. On April 11 multiple organizers, educators and non-profit heads said they were tired of a contemptuous attitude from city officials and an expectation that they had to beg for scraps of support for their vital work while other initiatives received far greater sums.

On April 11, most of Council sided with Hooper, though nothing will be final until they vote on the budget in early June. One member told the critics, once again, to tone it down. The backlash was considerable, and heading into election season the issue’s not going away.

The fire down below

On paper, “recurring and Non-Recurring Additions to the Base Budget,” wedged into an afternoon budget hearing, doesn’t seem likely to make sparks fly.

But over the past few months, controversy around both Hooper’s tenure as the city’s police chief and the impacts of gentrification have steadily built.

The APD had a tumultuous decade, with five chiefs since 2011 and issues ranging from the evidence room to problems with morale, pay, retention and minority recruitment. Hooper, hired in 2015, came in trying to build a reputation as a reformer and uniter.

That crumbled rapidly last summer, as her leadership became more a source of controversy than consensus. After APD Sgt. Tyler Radford shot and killed Jerry Williams in July, the ensuing controversies revealed the force of long-simmering tensions about policing in Asheville’s black communities.

In the aftermath, Hooper was criticized for a lack of transparency and retaliation against critics. Things didn’t exactly ease when the department clamped down on ensuing protests, reviving tactics it had shied away from for most of a decade, including after-the-fact arrests and flatly misrepresenting some basic facts of the case to the public. In one case, Hooper refused to meet with one protest leader until she was handcuffed and in custody.

As this year began, groups like the NAACP and the Southern Coalition for Social Justice highlighted long-running racial disparities in the APD’s traffic stops and searches, calling for several reforms. The controversies continued as Hooper was silent when Officer Shalin Oza was caught on videotape in September throwing a teenager to the ground and outright defended Oza earlier this year when another video emerged of him carrying an AR-15 in the arrest of a group of black teenagers (one of them had a bb gun).

So when Hooper asked, during a larger Jan. 24 presentation to Council, for $1 million to hire and equip 15 more police officers in downtown, it collided neatly with both long-running and more recent public pushback over the APD’s leadership. It also joined with a perception among some that the city of Asheville has remained complacent in the face of a severe housing crisis and a wave of gentrification that’s hit minority communities particularly hard. Homeless advocacy, civil rights and left-wing groups, along with some downtown business owners, joined together to call for the $1 million to instead be directed towards housing or social services.

Since the mention in January, Hooper hadn’t defended or elaborated on the proposal further, which was incredibly unusual. Major budget proposals are usually discussed publicly by senior staff and any relevant committees well before Council’s budget hearings get going. After protesters packed the room at a committee meeting and the first budget hearing in early March, Council member Cecil Bothwell claimed the $1 million would be front and center at the March 27 meeting of Council’s Public Safety Committee. It wasn’t. Hooper didn’t show at that meeting, or any other committee meetings before Council held its final budget hearing on April 11.

The push for ramped-up policing did find defenders among local gentry and business groups, after Hooper or top police officials discussed the issue with them. The South Slope Neighborhood Association endorsed her proposal on April 4, the Asheville Downtown Association’s board on April 7, both in letters laden with very similar talking points to Hooper’s presentations.

At that March 27 meeting, critics of the hike shot back that this showed once again that the chief had major issues with transparency and responding to public concerns. But Hooper has her defenders too. At the same meeting Council member Julie Mayfield told the protesters to tone it down and not criticize the chief or the APD (full disclosure: I criticized Mayfield’s remarks at the time as representative of a culture in city government that tries to tone police public criticism rather than constructively respond to it).

April 11 was the last budget worksession of the year, but as the date rolled around there was still no specific time set aside for a report on stepped-up policing.

However, as protesters and local activists took their seats in Council’s chambers, it was clear that in some form, the issue was going to come up.

Debate on the dais

Public comment doesn’t happen at these worksessions, as they’re devoted to staff and Council wrangling over the destination for the over $160 million that makes up Asheville’s annual budget (the May 23 Council meeting will have a full public hearing on the budget, and they’ll vote on the final budget in early June).

The $1 million was presented, however, but it wasn’t set up as a single item. Instead it was split into two items tucked into separate, much longer lists of budget expenses for the coming year, with $567,000 for personnel and over $300,000 for their equipment and vehicles in the coming year (once they’re hired and trained, the total cost will be $1 million a year).

‘This request could not have come at a worse time’: Council member Brian Haynes criticized the proposed expansion, citing problems with a militarized police force and the need to invest in social services. File photo by Max Cooper.

But Bothwell asked about the issue, and Council member Brian Haynes then made a statement opposing it. While he praised Hooper for community outreach and changing the use of force policy to emphasize de-escalation, he said he felt the funds needed to go to rehabilitation and social services, citing a similar decision unanimously backed by Buncombe County’s commissioners in February.

“This request could not have come at a worse time,” Haynes said. “A time when African-Americans’ distrust of police forces across our nation are at an all-time high, a time when over a 10-year period roughly three people a day have been fatally shot by police in the United States, a time when police forces across the U.S. are militarizing at an alarming rate.”

He also criticized police targeting of peaceful protesters as another reason he couldn’t support the increase.

“I agree with much of that,” Bothwell said. “As chair of the Public Safety Committee I’ve asked repeatedly for more detailed about downtown crime statistics. The numbers I’ve seen so far are pretty general.”

“My impression is increased patrols make some people feel more secure but don’t necessarily make any impact on crime,” he added.

Hooper then, for the first time since January, weighed in on the increase, claiming with a series of slides that the current downtown unit was overworked and conjuring images of the problems facing higher crime cities like Chicago if the APD didn’t get $1 million more a year.

“The livability in Asheville is considered pretty good in most areas except for crime,” Hooper claimed.

Besides for referencing the department’s overtime issues, Hooper’s presentation relied on comparisons of the APD’s 2015 to 2016 crime numbers and on stats from the website AreaVibes claiming crime in Asheville was considerably higher than both the North Carolina and national averages, and that the city was relatively under-policed, with only 2.8 officers per 1,000 residents versus as supposed 4.8 per 1,000 average for the state. That last number, it would later emerge, is incredibly dubious.

“There’s a lot of development that’s planned, that’s already in the works and we haven’t had any additional officers to handle that work since 2010,” she continued.

Currently the city is divided into three patrol districts — Adam, Baker and Charlie — with the latter including downtown. The 15 additional officers, she said, will allow the creation of a new district in the center of the city, named David, and improve response times in both the core and South Asheville, “due to traffic and the shape of the city.”

Meanwhile, she claimed that crime was “all over downtown,” from shoplifting to assault and nuisances, and the current unit is struggling to handle it.

“In order to accommodate the crime load on Sundays and Mondays we have to have officers work overtime.” After the new district was fully established next year, she claimed it would save $375,000 a year in overtime.

Asked by Bothwell if patrols would help these issues, she claimed that “literally dozens of studies” backed up her position. Currently, with officers just handling calls for services, she claimed they couldn’t interact with the community. If the APD didn’t receive additional funding she claimed they would have to stop traffic enforcement and responding to some crimes entirely.

A slide shown by Hooper at the April 11 Council budget session, claiming the APD will have to stop providing some basic services if it doesn’t receive $1 million to massively expand downtown policing.

“That’s what happened in Chicago in 2013, they stopped responding to minor crimes, we sure know what happened there,” she said. “I would like not to get to that place.”

Vice Mayor Gwen Wisler broached the idea “to revisit” forming a Business Improvement District in an effort to put more resources towards downtown. That highly controversial proposal, to create a separate entity run by wealthy property owners and backed by its own tax revenue, floundered in 2013 after facing wide opposition. Mayor Esther Manheimer highlighted the potential overtime savings of adding more police officers while Bothwell clarified that the APD already has 20 vacancies due to turnover problems.

The main defender of the increase emerged as Council member Gordon Smith, who praised the chief, said opponents of expanded policing shouldn’t criticize the APD so harshly and asserted that many social services aren’t the city’s responsibility.

‘Other social services are not the function of the city of Asheville’: Asheville City Council member Gordon Smith defended the proposed $1 million for expanded policing downtown, and APD Chief Hooper’s controversial tenure. File photo by Max Cooper.

“We’ve got a lot of emails about this from folks who want to make sure City Council is supporting all the people of Asheville and ensuring justice and equity in the broader community,” Smith said. “We’ve also had a ton of emails from people saying that as our population grows we want to make sure our police presence can grow along with it and ensure that when you call 911 someone’s there to answer.”

He sided with the latter, and defended Hooper’s controversial tenure.

“The demands are greater than ever and the demands for level of accountability make perfect sense,” Smith said. “I think that part of the unfortunate side effects of that call for accountability has been the vilification of many officers who are incredibly ethical and incredibly hard-working who get caught up in the blanket move to make sure the police are accountable.”

“You’ve done the finest work of any of the chiefs that I’ve seen come through here,” Smith said of Hooper, citing the APD’s new use of force policy, “bridge building” within the department and better mental health training. “Our population has went up 28 percent since 1997, our police staffing’s gone up 23 percent. This will take us to 27 percent, so pretty on par with population growth.”

“Money for the police versus money for the people, that’s not something that resonates with me,” He continued. “That’s not how this budget process works or how our city works. I don’t think we have to pit one against the other.” He claimed the city was set to spend record amounts on affordable housing and transit (which is facing its own issues) and parks. “Mental health, substance abuse and other social services are not the function of the city of Asheville, they’re the function of the county of Buncombe.” That last remark drew derisive sounds from some in the audience.

Both the latter points are a bit dubious, whatever one thinks of Hooper’s proposal. Budgets are finite and choosing to increase police funding means that money won’t go to other uses or services. The city also in fact funds multiple social service efforts, including partnering with local non-profits and Buncombe County on matters ranging from homelessness to education programs.

“I’m a little resentful that we’re in this tough position,” Manheimer said, noting that the tourist trade strained Asheville’s services, but that by state law hotel taxes just went to fund more tourism. “We’re in between a rock and a hard place here.”

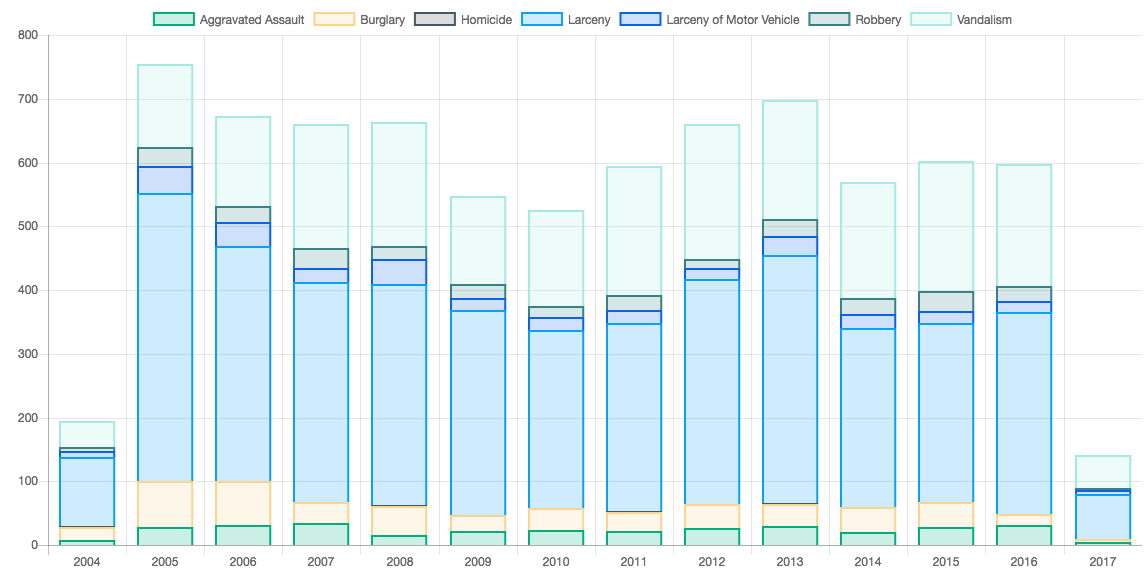

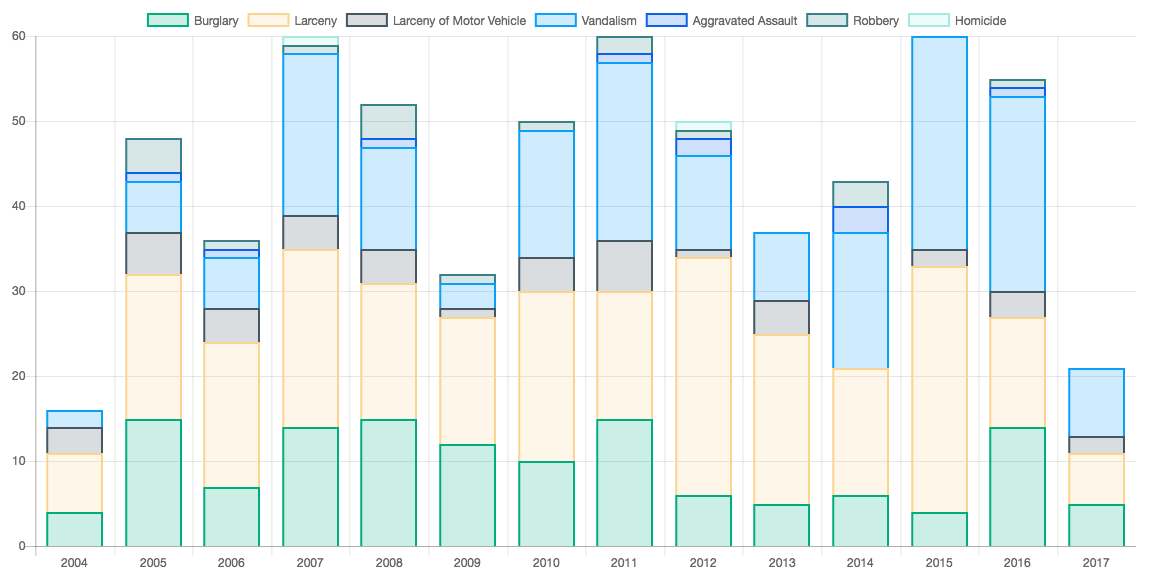

Downtown crime statistics: Numbers for a range of crimes in downtown from 2004 to the present, assembled from the city of Asheville’s publicly released data by open government advocates at AvlCrime.

In the end Manheimer, Wisler, Smith and Mayfield all vocally supported Hooper’s proposal. Council moved to discussing the crunch facing transit, including aging buses and federal cuts, as well as the need for improved bus service. After City Manager Gary Jackson warned them that “the budget is not elastic,” Council agreed to put a half cent property tax increase to cover the increased costs of transit and the police expansion. In the process, they agreed to increase the total pool of cash available to local non-profits to $200,000 a year.

One item that wasn’t discussed was $2.5 million more to increase city staff pay. When asked about that issue by the Blade after the hearing, CFO Barbara Whitehorn said the amount was unusually high (except for the recession, the city hikes staff pay every year) because they had major turnover problems in several departments, including the APD.

‘Stop having us fight tit for tat’

If Council was hoping for a respite in the early part of their formal meeting, they were disappointed. Criticism emerged over a related issue — how little the city gives to many social service non-profits — when Council voted on the consent agenda, a usually uncontroversial list of minor items they approve in one vote. This time, however, that list included the city parceling out its $158,400 “strategic partnership fund” to help non-profits, especially those dealing with issues facing marginalized communities. This year, the city received around $400,000 in requests, and at an earlier meeting, Mayfield had expressed frustration with some of the groups’ demands.

“There are a lot of worthy projects that were presented and it’s a shame our city does not invest in those projects,” Dawn Chavez, director of Asheville Greenworks, said. “It would only take $400,000 whereas other projects I hear proposed without much substance behind them were approved for $200,000.”

“I was appalled at some of the things that were said,” Libby Kyles, a teacher and director of YTL Training Programs. She criticized comments by Mayfield in particular. “I’m a native of Asheville, I know what it’s like to live in these communities, I don’t think that you do.”

“It would be really nice if instead of declaring your frustration you got up from behind your seat and visited the organizations applying for funding so you can see more of what we do and not make assumptions about what you think we’re not doing.”

Applying for the city funds was “so disheartening I don’t think I will ever apply again” and she asserted Council members were out for their own goals rather than the community.

Instead, Kyles said, Council must “start to take some responsibility for the state of black Asheville,” Kyles said. “Stop having us fight tit for tat over five, ten, $15,000 which isn’t nearly enough to do any of the work to do.”

She added Mayfield had “no clue” what it was like to run a non-profit as a woman of color, “you don’t know what it’s like for a person to have to beg over and over again to do things that should come automatic to any community.”

“We’re not a priority,” Dewana Little, chair of Green Opportunities and director of Positive Changes, stated bluntly. Little accused city officials of repeated disrespect and failures to understand the groups’ proposals. “I’ve seen different people in these racial equity trainings but nothing has changed. It was worse this year to have people slam their hands down on the desks in frustration, to talk down to us and devalue our work, the same disenfranchised communities the city has a focus to build up.”

“It’s getting worse,” she continued. “If equity and inclusions are y’all’s focus, you do not single out the minorities in the room, tell us what we’re not doing and talk to us like we are children. We are not children, we are adults and we are supporting the community that has been underserved and disenfranchised in Asheville for years. It’s not new, it’s been getting worse for years.”

Her organization, Little noted, had sought $50,000 from the city to fund a four-year program to help 50 students. Instead the organization got $6,500, so “thanks for the crumbs.” By comparison, she said, she didn’t see any hesitation from city officials in dropping “$300,000 for a consultant.”

After the remarks Mayfield apologized.

“I regret what I said, the way I said it,” she said. “I can only ask you to believe that my intention was good. But I did not seek to understand what you were bringing to the table before I sought to put on the table what I hoped would happen in that meeting. I apologize for that. I would be happy to come learn more about your programs.”

“Even the increased money we’re allocating is not enough, I don’t think any of us would agree with that,” “It’s hopefully just a start.”

“It was a really, really difficult meeting, illustrating how much need is unmet in our community,” Smith said, showing how federal and state cuts were shifting the burden to cities and local property owners. “We need advocates at the state and federal levels as well.”

‘These are boots on the ground’: Council member Keith Young said the city needs to look at providing more funding for smaller non-profits. File photo by Max Cooper.

Council member Keith Young thanked Kyles, praising her ability as a teacher and the work of similar non-profits and advocates.

“These are boots on the ground that may not get as much recognition as other non-profits,” Young said. “I do have a voice, y’all do have an advocate. It may not be enough, but things are being looked at.”

“The intention is to create tension so that your disappointed with these funding decisions,” Manheimer said, due to the state and federal cuts many groups are facing. “It’s disheartening to me.”

Bothwell asserted the cuts were an attempt to force progressive local governments to either cut services or raise taxes and then conservative groups like ALEC would back candidates in local political races criticizing them for doing either.

If Council’s budget passes, the total amount available to the non-profits will rise to $200,000, slightly more than the city manager’s current salary.

‘We have to stop pretending Asheville is a Southern utopia’

After the presentation of a poll on locals’ opinions on a district election system (which is worth delving into in its own piece), the barrage of criticism continued during the open public comment period at the end of the Council meeting.

Local poet and organizer Nicole Townsend blasted Council for opting for the police increase and for larger issues with its treatment of the local black community.

“I am angry, I am hurt and I can no longer sit back and play the role of respectable negro,” she said. “While I am not ignorant that the city funds efforts that are led by community members with the goal of enhancing the black community in Asheville, I am taken aback by what seems to be a lack of real support.”

She wanted the $1 million directed to help the community, but added that the city had to take steps far beyond increasing funding. The city needed to “prioritize the lives and well-being of black folks” hit hard by urban renewal and gentrification. For starters, it needed to embrace the proposals of Black Lives Matter, protect trans lives and fight sexism.

“We must stop pretending Asheville is a Southern utopia,” Townsend continued. “It is here that black and brown bodies are pushed out of their homes to make room for overpriced rentals, highways, restaurants and breweries. It is here that our police are harassing and intimidating people. It is here that black joy can only be found in small pockets nestled in communities that will soon be sick and disgusting results of white supremacy, white privilege and capitalism if you, City Council, don’t do something. Existing while black in Asheville will be a contradiction, because we are leaving.”

In a presentation countering Hooper’s, Amy Cantrell of BeLoved House asserted that the city is already over-policed, with a higher than average number of officers, according to 2015 FBI statistics (22.6 per 10,000), while the national average was 15.9. If the city passes the additional $1 million, she said, it would have the second highest number of per-capita officers of any city in the state.

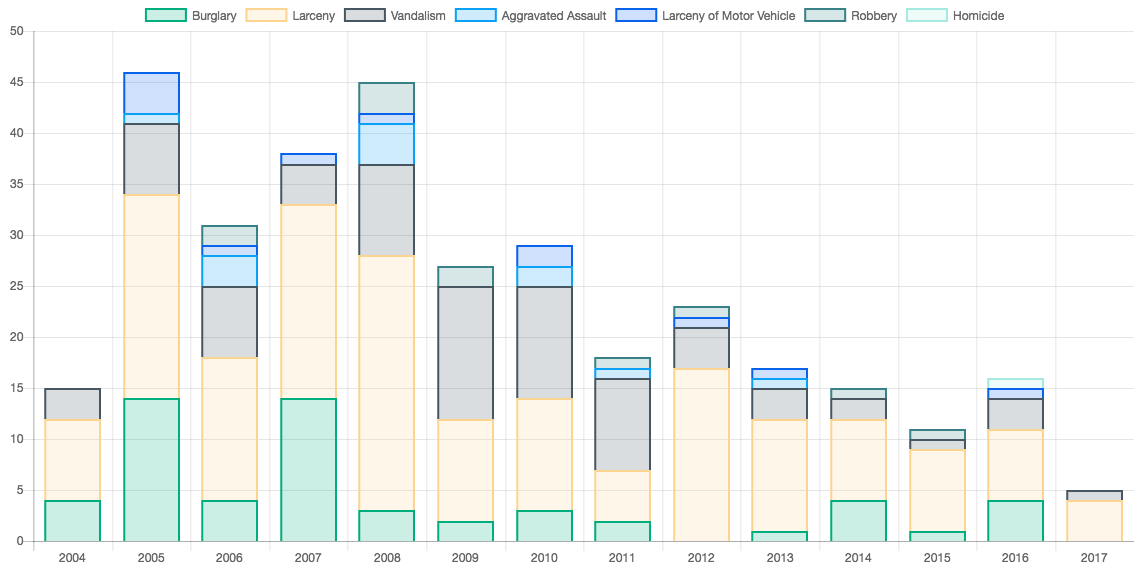

North Downtown crime statistics: Numbers for a range of crimes in the north part of downtown from 2004 to the present, assembled from the city of Asheville’s publicly released data by open government advocates at AvlCrime.

“I feel like there are many people in this city that have no voice, no place and no power, that are being left out of the decisions and the budgeting,” she said. “I am deeply concerned about the democracy of our city and the transparency of the budget process. I think it’s reprehensible that policing was automatically included in the base budget without any public discussion.”

She played the voices of impoverished and homeless people who swore that more policing downtown would, in the current environment, just mean more harassment. While the city digital display system was unable to play the slides in her presentation, she noted one showed 11 APD officers downtown to arrest just two homeless people.

“It’s unfair people are being treated like this in our own town,” she said. “This is the referendum of the people at this point, this will be an election issue. We need to get at the root causes of the crime: poverty, gentrification and homelessness.”

“There’s been some serious refutation of the chief of police’s presentation,” Moira Goree said. “Why does it need to be that much for a town this size?

“We were hearing earlier groups say not enough funding was available for their projects,” Matilda Bliss noted. “Yet many more times those amounts are being asked for by the police this year.”

Indeed, one of the same non-profit organizers that had condemned the city’s actions on that front also took aim at the police expansion.

“There is over-policing in our communities,” Little said. “I watched as a 13-year-old kid, night before last, was pulled over, held by six cops.”

“They’ve got the whole street blocked for one child of color,” she continued. “It’s not in Biltmore, you don’t see them over-policing on the hill tops. You see it in our community. There’s not a time I get in my car I don’t see the police messing with somebody. Not to say police are bad, but some things need to be reviewed. Before investing that money, accountability needs to be in place.”

She’s seen complaints about police go unanswered, seen others harassed and been harassed herself because her license plate tag light was out, “it’s really racial profiling.”

It’s an election issue

Agree with her overall or not, one of Cantrell’s assertions is indisputable: the police expansion is definitely an election issue. Already candidates are lining up and taking different sides on Hooper’s push for more police.

Of the incumbents, Manheimer and Wisler back the increase, as noted above, while Bothwell is skeptical of it.

Dee Williams, backed by the Green Party in this year’s local elections, has been active in pushing for police reform around traffic stops as one of the local NAACP’s leaders and has also repeatedly criticized the proposed expansion since earlier this year.

“In our communities we’re suffering immeasurably,” she said at the March 14 Council meeting. “There’s a lot more ways we can use that $1 million than putting it into the police department.”

“We don’t want another $1 million to be used to perpetrate more violence against African-Americans, folks who we have documented as receiving disparate treatment,” she added.

Kim Roney issued a statement on her website late last week, criticizing the expansion and saying the money could be better spent in many other ways.

“I have personally urged our council members to consider the state and national statistics when justifying more officers in our police force – especially when not all the available positions in the APD are currently filled, which leads to increased overtime,” she writes. “The main issue here is how our city is going to prioritize funding requests. If there is an extra million in tax dollars to allocate in this year’s budget, we should consider the example recently set by Buncombe County when they voted to fund community initiatives instead of a new jail.”

Rich Lee asserted the city should hold off for a year and see about the effects of the low/no-cost reforms proposed by the NAACP, SCSJ and local open government advocates.

“I’ve seen little evidence justifying it, compared to the need for better policing outside the city core. Downtown residents and business owners are opposed as well, ranking it below sidewalks and other needs in a survey last year, and petitioning against it online,” Lee wrote to the Blade. “From the window of my office near the transit station, I can see residents and the homeless being detained in a gas-station parking lot. These searches may turn up an outstanding summons or minor drug possession, but their effect on public safety is negligible, speaking as a downtown business manager; they disproportionately hit a vulnerable black community already mistrustful of law enforcement; and they clearly take a lot of manpower. That seems a high price to pay with little benefit that I can see in return.”

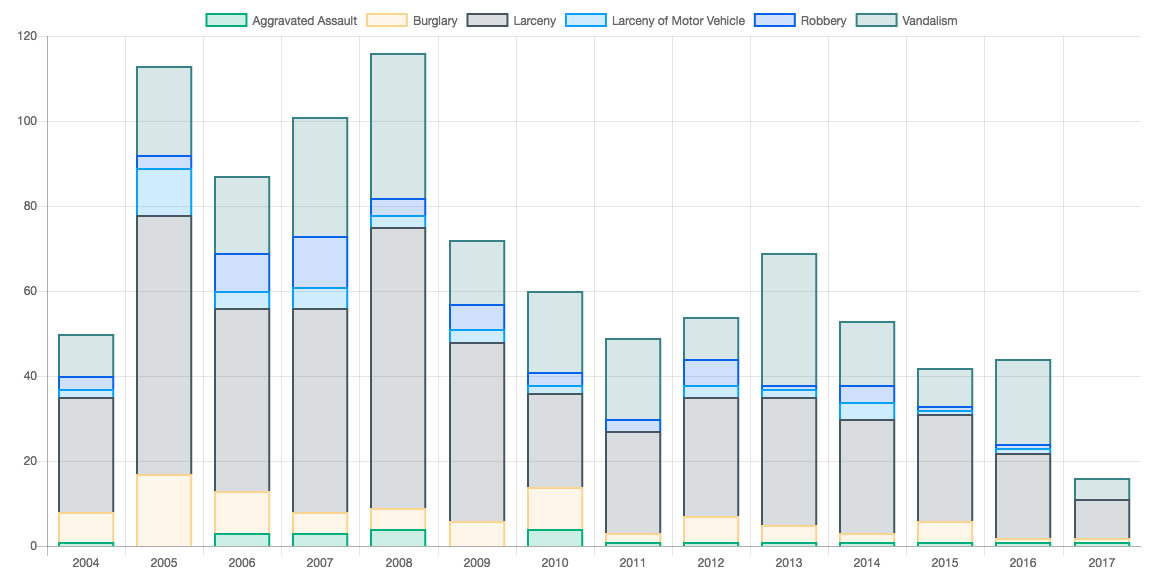

South Slope crime statistics: Numbers for a range of crimes in South Slope from 2004 to the present, assembled from the city of Asheville’s publicly released data by open government advocates at AvlCrime.

But Jeremy Goldstein wrote in an email to the Blade that he trusted Hooper and supports ramping up policing in downtown.

“I believe in hiring well qualified, caring and hard working people. Then, I believe in letting those people do their jobs. If Chief Tammy Hooper recommends additional funds in order to adequately protect the welfare and safety of our citizens, then I support that recommendation.”

Vijay Kapoor is somewhat skeptical of the increase, asserting in an email that he wanted to see more information about turnover and pay within the department before approving any additional hiring.

“I’m not necessarily opposed to hiring more police officers if there is a demonstrated need, but before we allocate additional money to do it and have to raise taxes to pay for it, I need to know what police department turnover is, whether there are unfilled vacancies, and whether there are other current police resources that the City could redeploy,” Kapoor writes. “If we have a turnover problem, then we’ll be spending money to train people who walk right out the door. Assuming that there is a demonstrated need to hire more police officers, I’d prefer to see the hiring phased in over a couple of years rather than all at once to see whether it’s having any impact.”

‘Simply not supported by the data’

As over a week’s passed since Hooper’s presentation to Council, there’s been some time to analyze the numbers and assertions she provided. On at least two important fronts, it seems those numbers are either dubious or lacking serious context.

The first is that Hooper has almost exclusively focused on two years, 2015 and 2016. In 2016, Asheville overall saw just a one percent increase in crime, but Hooper’s asserted that the concentration of crimes in and near downtown still justifies the new unit.

I admit, as a journalist who’s covered Asheville for over a decade, that focus seemed a little off to me. Asheville crime numbers are usually low enough, at least on major crimes, that a few more incidents in a neighborhood in a given year can look like a big spike. It’s important, then, to look at multiple years. Police officials usually aren’t shy about highlighting crime waves (like Hooper, they often use them to argue for more funding) but while there have been localized problems in given areas or neighborhoods, on the face of it 2016 didn’t seem like a massive departure from previous years.

That’s because it wasn’t.

Also concerned about the way crime statistics were being used and seeking to bring more context to the debate, local open government advocates created the AvlCrime site, drawing from the city’s own publicly available crime data. Those numbers monitor a range of crimes (aggravated assault, burglary, larceny, larceny of motor vehicle, robbery, vandalism, homicide). Unfortunately, many other crimes — while public record — aren’t yet included in the city’s public data. The makers of the site are pressing for the city to release more data to give a fuller picture.

But many of those crimes are exactly the sort of thing Hooper claims a new unit would address, and in many neighborhoods in or near downtown those numbers have significantly decreased over the past decade — as you can see from the graphs throughout this article — with 2016 representing, at most, a minor uptick. For one of the neighborhoods, WECAN (West End/Clingman Avenue) that saw an increase in 2014 and 2015, crime actually ticked down last year.

One of the people who composed those graphs is Patrick Conant, an open government activist who’s worked with a range of local governments and groups including the city of Asheville, BeLoved House and the NAACP on efforts related to data and public transparency.

“When I look at the South Slope, for example, we see a minor increase in crime from 2015 to 2016,” Conant writes in an analysis of the crime data provided to the Blade. “What that leaves out, however, is an over 33 percent drop in overall crime from 2013 to 2016. If we look at a wider timeframe, you’ll see many neighborhoods in Asheville have become safer overall — particularly those around downtown.”

“The argument that our population growth has caused a significant increase in crime is simply not supported by the data that the City makes publicly available,” he concludes.

The officer ratio numbers were also something that stood out to me, as did the fact that Hooper exclusively drew from the AreaVibes site in her presentation. That ratio wasn’t a number I’d heard cited in multiple pushes for more funding by APD officials over the years, and Asheville’s population has increased steadily for decades; it’s not like there was a sudden explosion of new residents just in 2016. APD officials have certainly complained about staffing before, but the focus has been on vacant positions or problems with retention.

WECAN crime statistics: Numbers for a range of crimes in the WECAN area, covering some of the River Arts District, from 2004 to the present, assembled from the city of Asheville’s publicly released data by open government advocates at AvlCrime.

He also raised some concern about the officer ratio numbers Hooper was citing from AreaVibes, so he sought out the same FBI statistics that the site uses. He said he’s not sure how AreaVibes uses those numbers to calculate its officer ratios, but is concerned it might include very small jurisdictions that can throw off the averages considerably. When he divided the 14,511 police employees in N.C. by the state’s 9.9 million population, for example, he found the state police per capita average at 1.5 officers per 1,000 residents, much lower than the 4.8 Hooper cited.

He also checked AreaVibes numbers against ratios, based on the same FBI numbers, provided at another site focused on government statistics, then compared those to other N.C. cities. Again, Asheville has a relatively high number of officers (2.8) per capita. Among other cities in the state with a similar population, Asheville again has a relatively high number of police per person, tied with Wilmington. Even compared to larger N.C. cities that are major tourism and population hubs, only Winston-Salem currently has more police per resident than Asheville.

For his part, Conant is concerned that Hooper has lobbied business groups instead of addressing criticisms and concerns from the public directly. Combined with the serious questions about the numbers in her presentation, he believes the current proposal should be rejected and the APD should have to resubmit it during the next budget cycle with clearer information and a more transparent process.

Now that her proposal has the backing of a majority of Council, Hooper is finally presenting the proposed police expansion to city committees. She presented it to the Downtown Commission on Friday (though she didn’t stay to answer questions) and is set to present it before the police committee on May 3.

But that majority is slim, possibly as little as one vote, and pressure from critics continues to mount with the final vote on the issue (and the rest of the budget) over a month away. The dodging of public discussion has intensified that pressure, not decreased it. Once again Council goes into an election year facing the stark fact that many Ashevillians’ patience is at an end.

—

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by its readers. If you like what we do, donate directly to us on Patreon or make a one-time gift to support our work. Questions? Comments? Email us.