The return of a state plan to gerrymander city elections and break black voting power gets a surprising boost from a Democratic senator — and sets the stage for a major civil rights fight

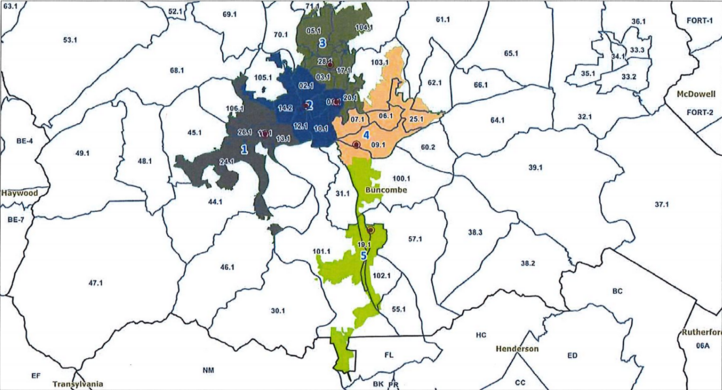

Above: A map of gerrymandered Asheville City Council election districts in legislation passed by the GOP-dominated general assembly. The map breaks up precincts with higher black voter turnout.

Gerrymandering is one of the hallmarks of the North Carolina General Assembly. After the far-right took power there following the 2010 elections, they’ve embarked on a spree, taking the previous Democratic establishment affinity for district-tinkering and ramping it up to previously undreamt-of heights. Absurd congressional districts blatantly drawn to elect as many Republicans as possible? Done. Racist state legislature districts carved to hold onto power at any cost? As many as possible. Voting restrictions tailored to exclude black North Carolinians “with almost surgical precision?” Most of the legislators in Raleigh love nothing more. It has, for awhile, been crystal clear that the state legislature would happily restrict the right to vote to white millionaires over 55 if they could get away with it.

Local governments haven’t escaped their wrath either. The general assembly passed bills gerrymandering and overhauling elections in both Wake County and Greensboro. But both were struck down by federal judges for being blatantly racist power-grabs (as were the legislative and congressional districts).

Over the past few years the GOP-dominated legislature has also set its ire on Asheville. While the idea of changing the city to a district system isn’t new, it took on a far more partisan cast as local conservative electoral fortunes declined. In recent years, gerrymandering the city became the favorite Hail Mary of Asheville’s dwindling and embittered right wing and their allies in Raleigh.

While Asheville City Council has its own divisions, the city’s elected officials have so far staunchly opposed these intrusions, as have Asheville’s people every time they’ve been given an opportunity to weigh in. They won a surprise victory against the first bill, in 2016, when the state House narrowly rejected the measure. But the push to slice up the city came back the next year, as Republican Sen. Chuck Edwards (whose district includes a tiny slice of South Asheville) pushed a plan to force Council to split the city into six districts. This time, the legislature passed it. In response, Council put the plan to a referendum in last year’s election, partly to bolster their chances in a future legal battle, and 75 percent of city voters cast their ballots against it. Council then refused Edwards’ directive that they redraw city elections according to his dictates.

This year, as Edwards introduced a bill to split the city into five districts, the proposal still hadn’t gained any local traction. Even the public comments the general assembly sought were overwhelmingly against the idea.

But the far-right picked up an unexpected ally. Democratic state Sen. Terry Van Duyn agreed to support the gerrymandering plan in exchange for an amendment shifting Council elections to even-numbered years (something neither Council or Ashevillians had requested or even publicly discussed). Importantly, the plan splits up the six key precincts where African-American candidates, due to an increasingly organized black voting base, did particularly well in the last two elections. The new districts are, bluntly, a racial gerrymander. Van Duyn backed it anyway.

While Van Duyn had shown a propensity for betrayal and political incompetence when she ditched LGBT communities (especially trans Ashevillians) to support the blatantly discriminatory HB142, she remained feted even in some more left-leaning circles in Asheville. To many liberals, her move came as a surprise given the overwhelming local opposition to state district plans.

With her support, the plan to impose an unwanted election system on the city and break black voting power in Asheville passed the state Senate unanimously. Local Democratic House representatives took the opposite approach, representing the wishes of their constituents and voting against it. Their party followed suit and the vote was far closer in that chamber, as they drew the backing of eight Republicans also opposed to the measure.

Earlier this month. Van Duyn asserted that caving to a plan overwhelmingly hated by most of her constituents, “will hopefully help get this issue behind us.”

Nothing could be further from the truth. Now the issue is front and center like never before, as the people of Asheville face uncertainty about when their next election will be and local black voters face a threat to their civil rights. Ashevillians have to rally (yet again) against a legislature they hate trying to run a city they love. How that fight will play out, and what actions Council will (or won’t) take, remain up in the air, as local leaders are considering their options. That said, given the plan’s pretty blatant civil rights violations, it’s likely heading to court one way or the other.

The years-long fight has seen some surprising twists and turns. There are many, many more on the way.

The plans

The original 1812 political cartoon of “the Gerry-Mander” coined the term and is too good to not use in an article on this topic

Ironically, there was a time where a local effort to pass district elections might have drawn broad support from across the political spectrum. Asheville operates on an at-large system, meaning every voter can vote for any open seat. For example, last year the mayor and three Council seats were up for election. Ashevillians got to vote for all three Council members (and pick a candidate in the mayor’s race), with the top vote-getters winning seats.

Under this system, Council members of all political stripes have historically come from the wealthier areas of North Asheville. In the mid-2000s, this became an increasingly prominent political issue, as residents of other areas of the city felt their concerns weren’t being heard.

However, this ended up playing out not in a major push for districts (though that idea was debated and discussed) but in Council candidates from other areas criticizing this state of affairs and trying to rally voters in other areas of the city to put them in office. Bryan Freeborn got a seat on Council in 2005 promising to better represent West Asheville. That proved just the beginning, as local “progressives” (a loose alliance of centrist and center-left Democrats) gained electoral strength in the ensuing years and West Asheville gained more representation. Chris Pelly won a seat in 2011 by focusing on East Asheville. Last year, Council member Vijay Kapoor (a vocal opponent of the state district plans), won in part by building up support in South Asheville, another area that hadn’t had a Council member for over a decade.

Meanwhile, as conservative electoral fortunes declined, the local far-right increasingly appealed to state legislators to impose districts, placing their hopes that such a system would at least allow them to hold a seat or two. At the county level they saw some success on this front. In 2011 far-right Rep. Tim Moffitt successfully pushed a bill to forcibly change Buncombe County commissioner elections to a district system (based on state House districts drawn by the Republicans to give them an advantage). Due to that system, Democrats now only have a narrow majority on the commissioners.

When it came to plans to gerrymander the city, conservatives claimed that they were just concerned about making sure South Asheville, historically the more conservative part of town, had representation. While the idea had come up before (Moffitt drafted up a bill in 2013 but never introduced it), it’s no coincidence that the first major push to gerrymander Asheville’s elections came after three experienced conservative candidates were wiped out in the 2015 local elections.

The first effort, introduced by then-Sen. Tom Apodaca in 2016, suffered a surprise reverse. While the plan passed the state Senate, in the House it narrowly lost. Democrats were joined by some Republicans who felt the bill was an overreach and were angered by Apodaca repeatedly ignoring the rules of their legislative turf.

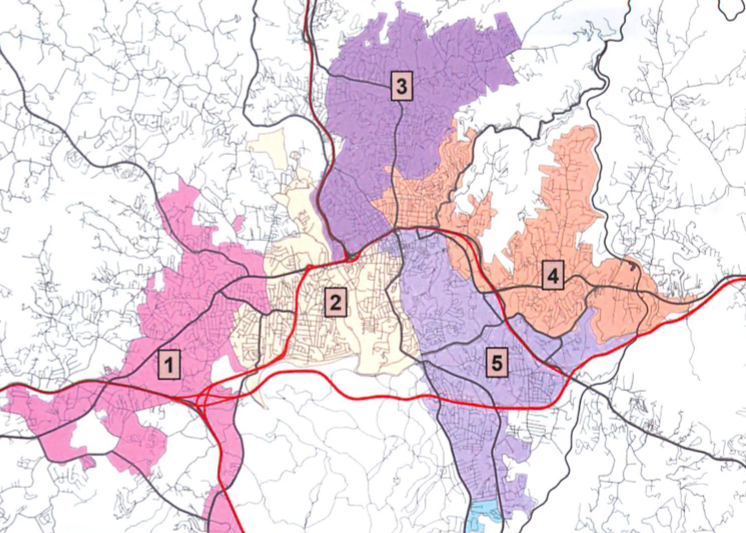

Part of then-Sen. Tom Apodaca’s 2016 proposal to split city elections into six districts. In a surprise, the plan failed to get support in the state House.

But Edwards, Apodaca’s successor, pushed forward again with a very similar plan in 2017. The gerrymander was obvious from the start, as the 2016 plan carved up different parts of downtown, broke up precincts with a strong black vote and “double-bunked” current Council members together in a way that would have forced many of them to run against each other. Notably, both plans also shifted Asheville from a completely at-large system to what would have been one of the most restrictive district systems in the state (most cities that use districts have a combination of district and at-large seats, or allow all voters to cast their ballots for each seat while requiring that some candidates come from certain districts).

Ironically, the push to use state-imposed districts to rig city elections has destroyed any vestiges of local support for the idea. Now, it’s overwhelmingly tied to an unpopular legislature in Raleigh, and fighting back against that is one of the only causes that still unites most Ashevillians in our often-divided city.

The point

So why is Edwards so keen to redraw Asheville’s elections? Like with so many things in our city (and state), race is key to understanding this. The general assembly’s attempts to rig Wake County and Greensboro’s elections were about curbing their political opponents overall, certainly, but their main targets were African-American voters.

Interestingly, districts have in some cases been supported by the left and civil rights campaigns as a way to increase minority representation. In my hometown, Elizabeth City, an at-large system favored white candidates (and was accordingly supported by the right-wing) in a majority black municipality. There the local left, progressives and civil rights activists engaged in a decade-long legal and political battle during the ’80s and ’90s to switch to a district system.

But the devil, as with any electoral system, is in the details. In cities where minority populations are mainly in one or two specific areas, districts can help ensure more diverse representation. But in Asheville, black voters are concentrated in several neighborhoods (like Southside, Burton Street and Shiloh) spread throughout different parts of the city.

With the current at-large system, if black voters in all these areas vote for common candidates and causes, they can sway not just a seat or two, but whole elections. Indeed, this has happened in recent years, going hand-in-hand with political organizing responding to Asheville’s particularly brutal de facto segregation. The past half-decade has seen rising black voter turnout in local elections, and it’s had results. Going into the 2015 elections, Asheville had an all-white Council. As 2017 closed Council had, for the first time in three decades, two African-American members.

So it’s not coincidence that the general assembly ramped up its plans to gerrymander Asheville after the 2015 elections made it clear the local right-wing wasn’t coming back, that they proceeded even after Kapoor’s victory disproved their assertion that South Asheville couldn’t be represented or that every plan proposed by the general assembly slices African-American precincts into different districts, diluting their voting power at a time when it’s becoming increasingly organized and effective. Indeed, both black Council members — Sheneika Smith and Keith Young — have vocally criticized the latest plan for exactly that reason.

Council member Sheneika Smith, who’s vocally criticized the state district plans as a racial gerrymander. File photo by Max Cooper.

That’s the most important part of this story. Not only is the state’s gerrymandering plan an attack on the rights of Ashevillians to determine how they’d like their own government to work, it’s also a blatant push to segregate the city further.

Asheville remains pretty unfavorable terrain for Republicans no matter how you slice it, but that doesn’t mean that Edwards and his far-right peers won’t gain from this bill. Something the right-wing has long realized, but liberals and even many leftists often forget, is that politics isn’t just a series of elections or single-issue campaigns. It’s interlocking cultures, organizations and movements, and most of it takes place outside of election season (though one also has to pay attention and fight then too). Damaging one’s enemies in one area damages them in others and decreases their overall chances of taking more power.

A more motivated and organized black voter base that shows up for local elections is universally bad news for conservatives because a large portion of their political power is based on propping up racial hierarchies. People who vote in local elections and become involved in local politics are overwhelmingly more likely to show up and organize around other political issues as well, and to vote in state and federal races.

But if whole communities have their say in local government reduced and their election system rigged from Raleigh to make it even harder for them to wield even a modest share of power, people are more likely to get dispirited and drop out of the political process entirely. Over time, that does shift things in a more conservative direction, and it makes the occasional upset in county and state legislature races less likely.

It’s unlikely Edwards has that whole rationale drawn out war room style, but he doesn’t have to: these methods are deeply steeped in conservative political culture, which is one reason the general assembly’s used them so often.

So it’s doubtful the district bill will give Edwards more Republican Council members (though it makes it a bit more likely), it will possibly result in more Van Duyns; well-off, basically status quo politicians who are easily outmaneuvered and don’t put up much of a fight.

The traitor

Unlike Apodaca, Edwards telegraphed what he was going to do and notified Council (though that didn’t reduce any of the damage his plans threaten to inflict) in advance. On June 9 he emailed Mayor Esther Manheimer with proposed district lines, even helpfully noting where current Council members lived on the map to show that the plans minimized double-bunking (“I hope you also recognized that I have worked to create as little impact as possible on the current council membership”). She quickly forwarded the message onto Council members and city staff.

While Edwards’ plan switched the proposed gerrymander from six districts to five (one Council seat and the mayor will remain at-large) and didn’t double-bunk current Council members the same way its predecessor did the bill still switches Asheville to a system locals had just overwhelmingly voted against and, importantly, still breaks up black voting power.

At first, it looked like this would play out like previous attempts, with Republicans having to push the bills over Democratic opposition. While that opposition couldn’t muster the votes to outright stop the plan, it has bolstered legal battles against similar state bills in the past (by making it easier to make the argument that local election gerrymanders were done over the will of both voters and most of the legislators in given municipality).

But something that surprised many Ashevillians happened. Van Duyn, rather than opposing the measure as she’d vocally done the last two times it was brought, up, instead supported it.

Why did she do this? Her explanations are, honestly, a mess. Van Duyn claimed that by having five districts instead of six the plan was better than its predecessor and that in return for her support she would get an amendment switching city elections to even-numbered years, which she believed might drive up local turnout.

But the amendment she was seeking didn’t have any prior support from Council or the public and, indeed, they weren’t even given an opportunity to discuss it. Manheimer told the Blade that while she personally likes the idea of moving city elections to even years and had discussed the idea with Van Duyn briefly, no Council member had sought the change or taken a position on the issue.

Manheimer adds that given the rest of the district bill “it’s still putting lipstick on a pig.” During the vote in the House, the district bill then picked up an amendment abolishing city election primaries (which passed), which Manheimer notes “came out of left field.”

There’s a good argument that having non-partisan local elections in the middle of a slew of partisan battles further up the ballot actually reduces organizing and voter interest. But Van Duyn never sought, seriously consulted or gave Asheville’s people an opportunity for that discussion.

It’s even more bizarre because from the political standpoint, Van Duyn had a solid position: oppose a bill most of her constituents hated and bolster the chances of it being thrown out in court even if it passed. In the process remind Democratic-leaning locals that the state legislature is once again being their tyrannical asinine selves, putting one in a solid position to rally votes and funding for those major elections that are happening in a few months.

But Van Duyn, as she showed in the fight over HB142, is both politically incompetent and steeped in a culture of compromise for its own sake. In both cases she gave away relatively strong political positions for paltry or non-existent concessions, then justified them by citing a need for compromise or “moving on.” This is the opposite of how functional political movements work: they instead push for ideas they support until they succeed. They fight ideas they oppose until they’re stopped or reversed. Bad ideas don’t get any better because one’s enemies keep bringing them up.

But in centrist political culture, compromise isn’t simply a political tactic that may or may not make sense depending on the circumstances, it’s a sacrament. Getting a compromise is regarded as a win in itself, no matter how incompetent it might be or how much it might hurt one’s constituents.

Also, like with the anti-LGBT bigotry of HB142, it’s not a compromise where Van Duyn has to give up anything that impacts her. Asheville’s state senator is an extremely wealthy white person who lives outside Asheville in the ultra-rich enclave of Biltmore Forest. She’ll be fine.

This is where I have to add that listening to marginalized communities is really, really important. The trans community and many of our allies were shouting about the damage done by Van Duyn for a long time, but far too many still treated her like some sort of social justice champion.

How a politician treats communities on the front line of oppression isn’t an exception or footnote; it defines who they are and tells you what they will do when the chips are down. If more Ashevillians had been willing to put serious pressure on Van Duyn after HB142, she would’ve been a lot less likely to turn coat on the gerrymandering plan. We’ll see if the lesson takes, or if Van Duyn will remain lauded even though her legislative record now largely consists of joining Republicans to pass two pieces of bigoted legislation hated by her constituents.

The uncertain path

How will city officials respond? So far it looks like their position remains one of opposition, though according to Manheimer they’re still deciding on the specific way to fight the gerrymandering plan.

“We have pretty consistently opposed any plan to district the city,” Manheimer tells the Blade. “As far as I know that hasn’t changed.”

“It did turn out differently than the local legislation that passed last year,” Manheimer added “We’ll need to have a discussion about how best to deal with this legislation now that it’s become law. My first thought was ‘well let’s put it back to a vote’ [via a referendum] because we the people voted against six districts. Should we do it that way or should we just file a lawsuit? There’s a lot to chew on.”

She shares, she says, concerns about the impact on minority turnout “and in these legal battles, that comes up a lot.”

Earlier this year, Manheimer notes she and other Council members visited state legislators in Raleigh and briefly discussed the bill when they were there for the League of Municipalities summit, and even sat in on a judicial redistricting hearing. Manheimer describes the legislature’s process for drawing districts as “a railroad job.”

As mayor, she says she met with Edwards frequently to urge him to change or drop the plan entirely and talked to Van Duyn before the bill hit the Senate floor.

So far no Council member’s publicly said they’re willing to let districts go through without a fight. Smith and Young have condemned the latest plan vocally. Kapoor, in a July 4th message to the public, noted he’d had breakfast with Edwards and “left with a better understanding and respect of the other’s point of view.” But while he believed the legislator’s motives were sincere and honorable (the racial gerrymandering part didn’t get mentioned) Kapoor also wrote that he still disagreed with the districts bill.

Rather than put the matter to rest, the redistricting bill has likely just set off a lengthy legal and political battle. Even on the off chance the city doesn’t take legal action, numerous civil rights groups could and likely will (as happened with other gerrymandering battles) due to the pretty clear damage Edwards’ bill causes to black voters.

From Biltmore Forest, it might look like the issue’s now in the past. The view from Asheville is a very different story.

—

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by our readers. If you like what we do, donate directly to us on Patreon or make a one-time gift to support our work. Questions? Comments? Email us.