For nearly 40 years, the TDA has spent significant tax dollars to market Asheville to the wealthy and privileged — and done untold damage. It’s time to abolish them and chart a new course

Above: The construction site of the new Marriott hotel on Merrimon Avenue, which demolished a local diner and gas station. One of many hotels, driven by the TDA’s marketing budget, that are taking away amenities for locals to create more spaces for wealthy tourists

The Tourism Development Authority commands a budget of nearly $20 million in hotel tax dollars, controlled by a small board of only eight voting members, all with vested interests in tourism. While communities throughout our area struggle with a lack of services, with being pushed out, the hotelier-led TDA markets Asheville to the white and wealthy. It is a major factor behind the rampant tourist growth that has cost us dearly.

In recent years, the TDA has been under increasing pressure. Locals, concerned about its massive budget and complete lack of accountability, have pressed for hotel tax dollars to instead go to housing, infrastructure and more.

Last Tuesday, thanks to public outrage, Asheville City Council unanimously passed a year-long moratorium on hotels. Locals rightly tied the TDA and the “extractive” hotel industry to woes with increasing segregation and other ills. Some even suggested reining in the TDA or changing up the funds they receive, perhaps (as Council member Brian Haynes proposed) taking away their marketing budget. That would require a change in state law.

As a community, we need to go farther. The TDA needs to be abolished entirely, and it’s fully within local government’s power to do so. No state law required. The TDA needs to be ended so we can start reversing the damage done and focus on building an economy that actually works for the people who live here.

While state law mandates that Buncombe’s hotel tax goes entirely to the TDA, it also gives the county commissioners the ability to end that wave of money entirely by voting to repeal the tax. That would end the TDA’s massive public subsidy and, with it, the organization itself.

My perspective is informed by having lived in and near Asheville since the 1980s, my connection to marginalized communities in Buncombe County, and research. This essay echoes insights from The tourism machine, an illuminating piece written by Matilda Bliss which was published by the Blade in April. That article thoroughly outlines the history of the TDA and the racism and classism found therein. It traces money and influence, and calls for us to shift our energy and resources towards cooperatives and mutual aid.

With a rotten foundation and an enormous budget to spend without recourse to expand a problematic industry, there is no reason for the TDA to continue.

Exploitation from inception

“The tourism machine” looks at local history related to tourism starting in the 1920s — let’s look further back as well.

The first non-native “tourists” to Buncombe County were led by wealthy Spanish conquistador Hernado de Soto, who passed through this area in 1540. As is well-documented, the “discovery” of what’s now WNC was tragic for the Indigenous tribes who were the original stewards of this land.

From that point on, waves of rich people have arrived and shaped things to their liking and profit. While we also had many working class settlers in this region, the wealthy have had held and exercised power out of proportion to their numbers, as they do everywhere. This country’s economy is built on the theft of land from Indigenous natives and the extraction of labor from enslaved and exploited people, and our local economy mirrors that fact.

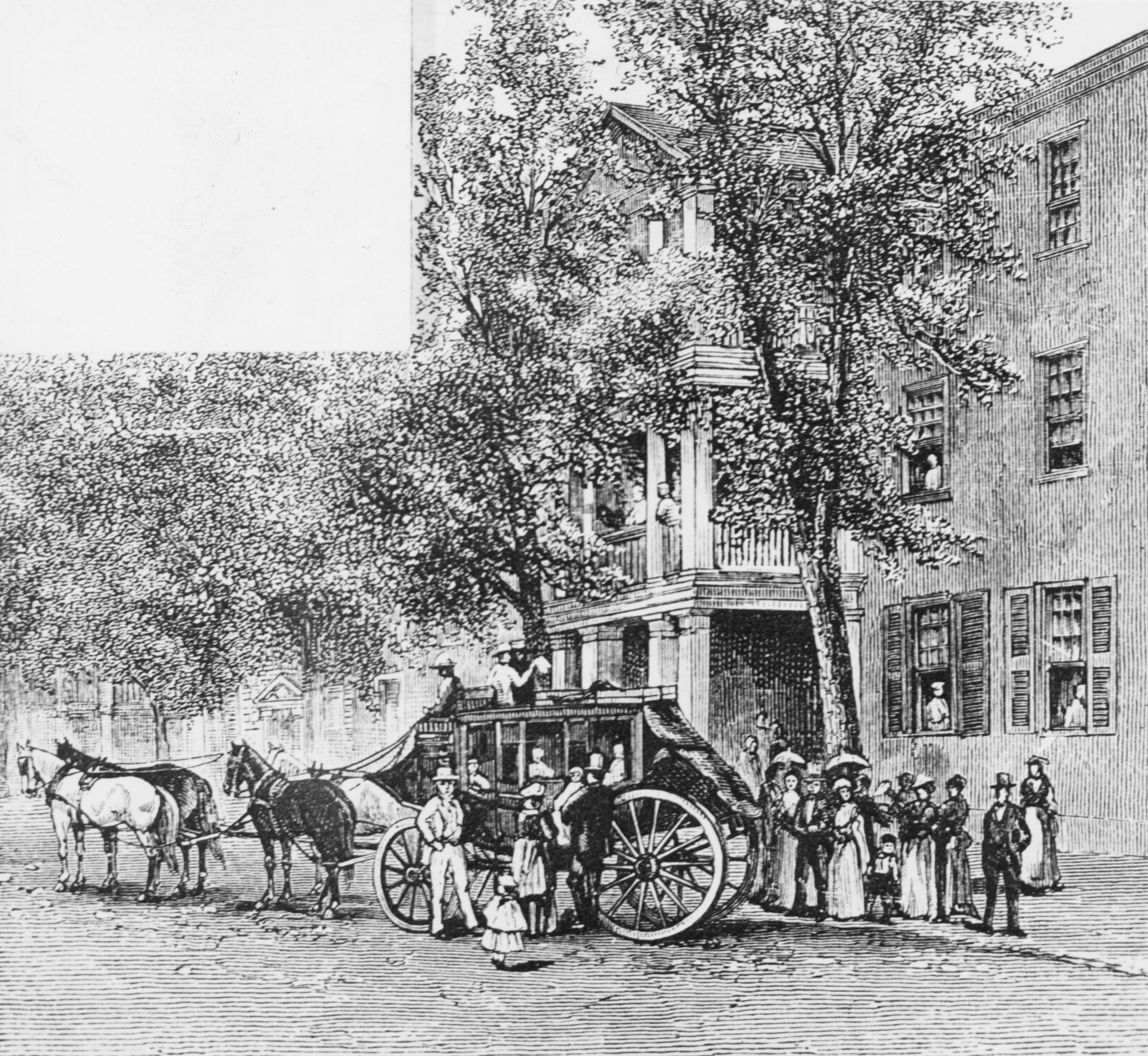

The Eagle Hotel, Asheville’s first “luxury” hotel, staffed by enslaved people and owned by one of the most prominent slavers in the county. Image from the North Carolina Collection, Pack Memorial Public Library, Asheville, North Carolina.

In 1814, James Patton, at the time the second-largest slaver in Buncombe County, opened Asheville’s first “luxury” hotel, the Eagle Hotel. The hotel was operated by people he enslaved. Patton was then a key partner in the construction of Buncombe Turnpike, which was built using enslaved labor and opened 1827. The Turnpike greatly increased traffic and commerce into Asheville, and visitors to Patton’s hotel.

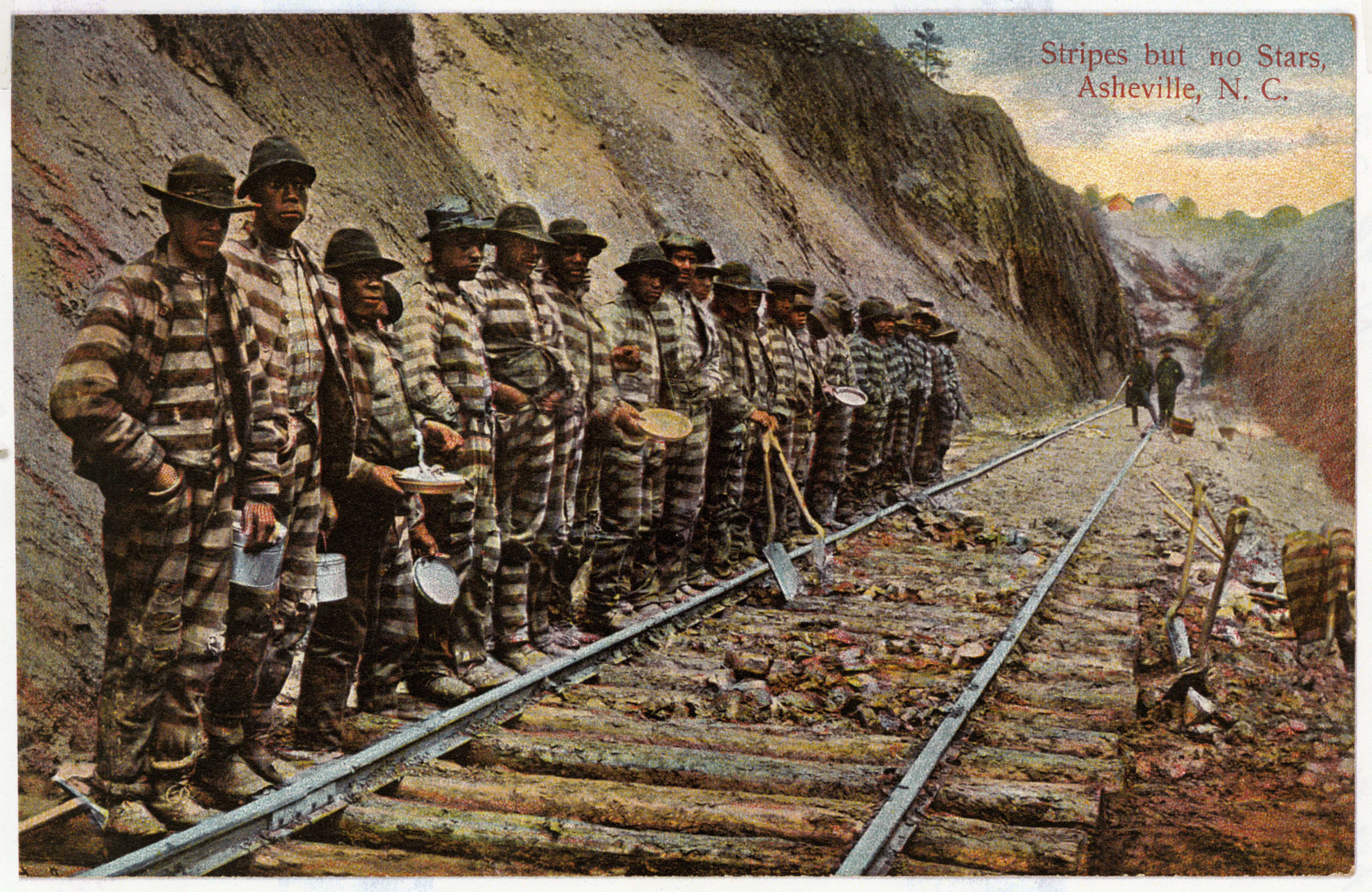

Another significant transportation project, the Western North Carolina Railroad, was built using incarcerated labor and opened in Asheville in 1880. The majority of those incarcerated were African American, the earliest victims of the post-emancipation racist criminal “justice” system which jailed people for fabricated “crimes” like “loitering.” This system was an adaptation by whites wanting to intimidate and re-enslave freed Blacks. It continues to operate the same way today, destroying the lives of millions.

Postcard of incarcerated railroad workers, 1880s. North Carolina Collection, Pack Memorial Public Library, Asheville, North Carolina.

Thanks to the turnpike, the railroad, and word of mouth, by the mid-1880s Asheville had become a popular destination for wealthy white tourists from South Carolina, Georgia, and beyond. From early on, the city of Asheville advertised to attract the rich to visit, promoting attractions such as luxury hotels and golfing. Like today, some of these monied visitors chose to buy property and build here. Examples include George Vanderbilt, E.W. Grove, George W. Pack, and Julian Price. Their legacies continue to generate wealth as tourists pay steep prices to fetishize the decadence of the Biltmore House and Grove Park Inn, etc.

I share this early history to reinforce that we should have no illusions about the roots of tourism, on whose backs it was built, what type of tourists we have courted, and who benefits.

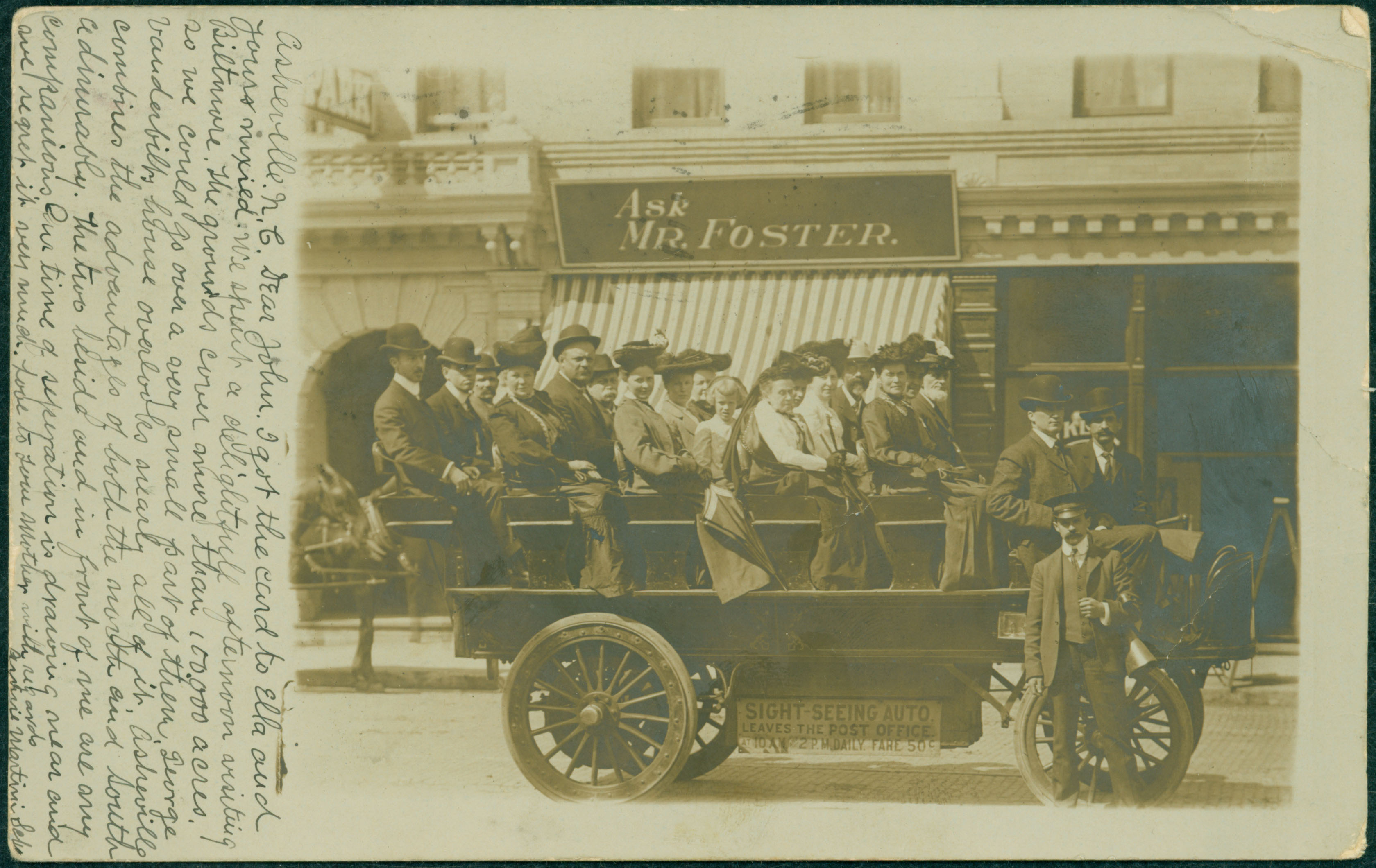

‘Sightseeing Auto,’ 1905 North Carolina Collection, Pack Memorial Public Library, Asheville, North Carolina.

The damage

It is difficult to digest the cumulative damage caused by encouraging rich white people to visit for over a century and a half. While there has been an ebb and flow of the influx of visitors over the years, a tourist-pleasing mentality has prevailed. Decision makers have focused on the dollars that flow in with tourism, while ignoring the problems caused by it. There has been scant effort on a governmental level to curb the negative impacts of a tourism-driven economy, even as our infrastructure is strained and many residents struggle to survive. With little resistance, powerful hotel mega-corporations and transplant entrepreneurs (who arrive with capital to open breweries and related businesses) are profiting off of the tourism machine. Meanwhile, residents suffer from the deluge of vacationers.

Systemic racism

Not unlike the plantation owners who came to vacation here in the 1800s, a case can be made that since its inception, the TDA’s target demographic has been rich white people.

In recent years the TDA’s own marketing plans describe their “primary audience” as “elite empty nesters.” While they do not specify race in their target demographics, our country is one where the “elite” are primarily white and cishet. Moreover, the TDA’s photography, choice of advertising platforms, and messaging have long pointed to a white target (as did customer profiles of white women shown at a TDA marketing presentation I attended a couple of years ago).

This slanted marketing has reinforced the ways that Asheville is segregated and dysfunctional when it comes to equity and diversity. While the latest marketing plans claim to be casting a wider net, a real pivot seems unlikely, and we still face the cumulative impact of advertising thus far. Of great concern is the fact that TDA’s staff is and has been almost 100 percent white. TDA President Stephanie Brown defended this at a forum this summer by asserting they were looking for people “with a certain skill set,” which reeks of racial bias. This isn’t only with staff; there are only a small handful of businesses owned by people of color being promoted on the TDA’s exploreasheville site.

A focus on white tourism has exacerbated the particular brand of systemic racism found here. As Bliss documents in her article, the decisions that led to the destruction of Black home and business ownership, culture, and community through urban “renewal” were in part the result of a desire to appeal to visitors. The fact that Asheville has the highest number of police per capita in the state, with that department consuming a full third of the city’s budget, reflects a pattern of wanting to make certain demographics (wealthy, white) feel “safe.” Little has been done to address the fact that this same overfunded department terrorizes communities of color, particularly the Black community, with the attack on Johnnie Rush being a case in point.

It appears that justice for marginalized residents does not fit into the equation of catering to fancy folks from out of town.

Gentry-fication

With high dollar advertising drawing them in, we see “elite empty nesters” and “power families” (a secondary TDA audience) filling the streets downtown and staying in houses that should be rented to locals. We see their expensive cars and clothes. Later, we see them buying houses — in many cases second and third houses — in our neighborhoods (with cash). When they become landlords, we see them raise the rent. We feel the pinch of gentrification and the affordable housing crisis their arrival contributes to.

The super-luxury Arras hotel, only open to the wealthiest visitors and now dominating the skyline of downtown

I know the over-advantaged are prone to arrive and colonize. At the same time, I see absolutely no reason to spend millions of advertising dollars to invite them to do so. Instead, we need to center those who are struggling to survive this unsustainable system.

Environmental woes

It is no secret that the growth in tourism has led to a proliferation of hotel construction and other development. This has meant countless negative environmental impacts, ruined views, ugly architecture, tons of trash, toxic materials, runoff, and a strain on public utilities. With thousands of tourists flushing toilets across the city, it is no wonder that sewage lines are breaking and filling local waterways with disgusting levels of e coli. Then there are the negative impacts of traffic including increased pollution. The overuse of surrounding natural areas. And on and on and on.

In the last 10 years we have lost over 10 percent (1600 acres) of the tree canopy in the Asheville city limits. This undermines our ability to manage runoff, and lessens our capacity to counter climate change and support the new economies we need. Tourism generates eight percent of human-produced carbon emissions worldwide. How can we justify growing this industry in the face of extreme environmental collapse?

We’re screwing up the ecosystems we live within, and upon which we all depend, for people who are just passing through.

Economic inequality

The issues outlined thus far are being exacerbated by an industry that is not producing significant numbers of living wage jobs nor improving living conditions in our community. As international corporations, hotel profits are not reinvested locally. Instead, tens of millions of dollars are extracted annually by hotel brands in the form of royalties and fees. Once again, the rich (in this case, corporate hotel CEOs are getting richer on the backs of exploited workers. While some locally-owned businesses that cater to tourists do pay and treat their employees decently, they’re the exception. Because of gentrification, workers are grappling to find housing, access to reliable transit, and other supports that would make living here sustainable. The dominance of the service industry — and the lack of unions — means jobs and income are unstable.

Creating systems that work for the working class and our neighbors dependant on fixed incomes is not a priority of the powers that be. Meanwhile, the TDA exists to get “heads in beds” for hotels, which then grow its already out of control budget even more. A budget spent inflating an unsustainable industry and pushing its costs onto locals and the marginalized.

It’s a self-perpetuating disaster.

False narratives

Of great concern is the damage caused by false and misleading narratives manufactured by the TDA about who and what is Asheville and Buncombe County. With white staff hiring out-of-town marketing firms to spend multi-millions of dollars advertising with a specific, slanted agenda, the TDA is not shaping narratives in ways that are reflective of or accountable to residents. Instead, our collective narrative is being obscured by a handful of people with way too much money to spend on a narrow agenda. A caricature of our culture is being sold to drunk sightseers — this has led to wasted packs of sightseers belligerently threatening the dignity and safety of locals. What are we losing in this process? I believe the TDA has corroded our regional identity.

Our story is being sullied in dangerous ways.

Pull the plug

If this all feels hopeless, I am happy to share that the Buncombe County Commissioners can vote to eliminate the TDA. The TDA often hides behind state law, portraying their existence as inevitable. It is not. Buncombe County has control over accepting and distributing the tax that funds the TDA. The commissioners can, if they choose, refuse to do so, ending the TDA.

Knowing Asheville and the neo-liberal tendencies of those in positions of influence, it is inevitable that many will disagree with this demand, proposing reform instead. Detractors might point to the (insufficient) community input process the TDA has undertaken, the slight expansion of their marketing demographic targets, City Council’s approved one-year hotel moratorium, economic concerns and, um, I don’t know what else.

I am not alone in saying that real reform of the TDA is impossible. The legislation that governs it is too limiting. As with most if not all large institutions, it is hardwired to produce better results for the white owning class. “Reform” or no, the vested interests calling the shots will continue to line their pockets, strain our resources and distort our stories all while undermining the efforts of those of us working towards a Buncombe County where everyone can thrive.

Let me reiterate — the TDA can be dismantled. It will just take many voices joining the chorus of “Abolish the TDA” to give the county commissioners the political will to pull the plug.

What we will find if that happens is not darkness from a gigantic light being turned off, but instead the brilliance of finally being able to see countless smaller lights shining.

Overtourism or an alternative

There have been a number of stories in the past few years about cities suffering from the ills of “overtourism.” Asheville belongs on the list. Today, as Bliss states, we have “an annual visitor to resident ratio of almost 15 to 1 and a ratio of 42 to 1 when considering all visits including day trips.” Compared to other tourist hubs across the nation, this is as extreme as it sounds.

Those of us who live here and are fighting for a better quality of life for ourselves and our neighbors are doing so while being vastly outnumbered by people who are only having a transactional relationship with our community.

The stress and strain on our streets and psyches is real. The damage done to our communities is devastating. The way forward is to use our strength, not playing by their rules. Instead of begging for whatever concessions the TDA might offer to save face, we should remind them of who really holds the power, and end their reign.

In response to overtourism, popular destinations across the world are taking bold actions to stem the flow of tourists and minimize their negative impacts. Amersterdam has even chosen to cease promoting itself altogether. Let’s join them! In this age of social media, even if the TDA stopped operations today, word of mouth would continue to spread. Businesses that benefit from tourism would continue to market themselves, just not as an overfunded monolith. We are too well established of a destination to disappear.

And perhaps, if tourism slowed, we could get some breathing room to reinvent ourselves. To balance our ecosystem and shore up our infrastructure. To find ways to bring back the Black people and artists and activists who were pushed out. To build cooperatives and sovereign economies that break the status quo of local government handing out land, incentives, and cash to the well-off. To depend on each other more than transient visitors.

The people have the tools and the will to create a more just, joyful, and sustainable city and region. Eliminating the TDA (and the compounding problems it causes) will eliminate key barriers to our success. We deserve better.

—

Ami Worthen is an activist writer, community collaborator, and musician committed to collective liberation. Her work is centered around the fact that, as Fannie Lou Hamer said, “Nobody’s free until everybody’s free.” You can find Ami’s writings and collaborations here.

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by our readers. If you like what we do, donate directly to us on Patreon or make a one-time gift to support our work. Questions? Comments? Email us.