Beyond the glamour of Asheville’s name and the millions spent on PR lies an industry that is anything but natural or generous. As more locals are underpaid and pushed out, we must delve into the history of Asheville elites’ obsession with tourism, its ties to segregation — and how we might push back

Above: a slide from an official Tourism Development Authority presentation, marketing a glitzy, gentrified Asheville where tourism is the main focus and locals have little place

Who runs Asheville? That issue is on the minds of many as the Tourism Development Authority takes millions of hotel tax dollars, uses it to promote our city as a playground for the elite and even seems to hold sway over swing votes on Council. The industry they promote so heavily — and to the exclusion of everything else — is devastating to wages, housing costs, traffic, parking, public safety and our quality of life.

Asheville’s tourist economy isn’t an accident of geography or history. It was deliberately constructed over decades around the needs of corporate outsiders, local gentry and their allies, who have capitalized on weak state laws and intentionally pushed a segregated city that leaves locals little place or power.

At their meetings, members of the TDA’s governing board and their allies go far beyond promoting tourism, expressing blatant disgust for the homeless and working class, openly talking about focusing on bringing wealthy, white tourists to town and opposing NAACP-backed police reforms.

The TDA’s origins lie back in 1983. After decades of expansion into North Carolina and other places by outsider-owned chains of hotels, restaurants, and other travel-related industries — at the expense of lodging, eateries and other businesses that were locally owned and operated — hoteliers and their allies across the state had successfully lobbied the state legislature for a tourism tax.

Buncombe was one of the first local governments to get the go-ahead (each local government that has a hotel room tax must get specific approval from Raleigh) and its tax was set-up exclusively to benefit hoteliers. At least two-thirds of the tax would fund promoting their own businesses, thus putting local names on what remained essentially corporate products. Furthermore, no share of the revenue was directly under the control of any elected official. Instead, a group of hoteliers (the law deigned to let local governments pick which ones) would control this increasing pot of cash. The tax was initially two percent in Buncombe County has since increased to six percent on each room rented. Instead of sticking with the two-thirds minimum, Buncombe County’s TDA chooses to place three-fourths of the tax back into tourism promotion. While Asheville hosts the overwhelming share of hotels, none of the funds go directly to the city government.

As many residents, especially those who are Black or Brown, struggle to make ends meet, local millionaires and out-of-town billionaire CEOs reap the profits of what Asheville has to offer. The Buncombe County TDA fuels this exploitation. When outsiders and local millionaires decide the basic functions of our city, perhaps it’s time to discuss our sovereignty: who runs this town, and for whom they do so.

Divided and Hesitant

Right now, our city’s elected officials seem mostly reluctant to challenge the hotel industry in general or the TDA in particular. Last month, Asheville City Council officially ended their unofficial ‘moratorium’ on hotels, passing two, both by a single vote. Mayor Esther Manheimer — a key swing vote both times — cited the TDA’s stated intention (and it’s just an intention, they’ve made no firm promises) to fund infrastructure and study using the remaining fourth of its budget to (maybe, someday) benefit people that aren’t millionaires or tourists as her reason for dropping her hesitation about opening the hotel floodgates.

Somewhat surprisingly, each hotel secured key votes by two members who have generally rejected hotels, expanded police budgets, and other prior gifts to the elite. These votes brought forward an Extended Stay near Mission Hospitals (with Council member Sheneika Smith’s support), a project of developer Monark Patel and his company Milan Hotel Group and a Family Lodge (with Council member Keith Young’s support) a project of developer Al Sneeden, owner of several local multi-million dollar luxury developments. Six hotel conglomerates and a host of local companies and developers including Vanderbilt scions, Sneeden and Patel have already invested tens and hundreds of millions of dollars into such properties, holding sites of both current and future hotels.

More is coming. Next Tuesday, April 23, Council will vote on turning the Flat Iron building into another luxury hotel. If they approve that proposal, it will kick out around 70 local businesses and organizations, take away 40-plus parking spaces from public decks, and place a hotel across from two other hotels.

So what are we as residents demanding in hopes of damming the flow of millions of tourists each year in favor of an economy that works for everyone?

While we wait, the economy created by gentry, hoteliers and massive hospitality corporations is stifling any and all attempts to make Asheville more affordable.

There’s a lot of money in keeping Asheville unaffordable and underpaid. Last fall Patel and his business partner Pratik Bhakta brought forward a proposal for a 103-room Extended Stay hotel at 324 Biltmore Ave, near Mission Hospitals. But things didn’t quite go as expected. Council members Keith Young, Brian Haynes, and Sheneika Smith were joined by Mayor Manheimer in rejecting the proposal, Milan Hotel Group withdrew the measure to avoid losing a vote outright, which would have required them to wait a significant amount of time before approaching Council again, or bring back a different project entirely.

But here is why Milan Hotel Group and many other hoteliers continue trying (and perhaps why they continue to win): they’re wealthy local gentry tied to even wealthier outside corporations. According to its website, Extended Stay American licenses or owns 627 hotels, in 2017 it earned $1.3 billion, held total assets of more than $4 billion, and supplied CEO Jonathan S. Halkyard with salary, stock and other compensation which nets an annual $1.7 million.

Moreover, Milan Hotel Group was looking to add to its “diverse” portfolio of national hotel brands which have chosen Asheville as earning grounds. Milan owns and pays licensing fees on several hotels in the area, including a Courtyard by Marriott, a Super 8, a Country Inn and Suites, a Clarion Inn and a Fairfield Inn and Suites. The Courtyard, which is under construction, is valued at $14 million.

While the owners of these hotels might be wealthy locals, they often license marketing and design from hospitality behemoths, who often rake in lucrative fees and royalties.

Parent companies from which Milan Hotel Group licenses include: Wyndham Destinations, owner of Super 8 (annual revenue: $5 billion). Choice Hotels, owner of Clarion (relatively modest annual revenue of $1 billion). Radisson, owner of Country Inn and Suites ($4.4 billion). Marriott, parent company of Courtyard and Fairfield Inn and Suites has a whopping revenue of $22.89 billion, with Bill and Richard Marriott, descendants of the company’s founder, both comfortably billionaires. Marriot also licenses Asheville/Buncombe County based-hotels Sheraton, Renaissance, SpringHill Suites, AC Hotels, Aloft Hotels, Residence Inn, and the Grand Bohemian Hotel in the Biltmore Village.

Architects’ rendering of part of the 155 Biltmore project, a recently-approved luxury hotel owned by developer Albert Sneeden

For just a single hotel Marriott collects initial application fees (anywhere from $50,000 – $75,000) and — most importantly — royalty fees, taking a percent of gross annual revenue, It even scrapes two to three percent of food and beverage revenues at hotels such as Courtyard.

Other hotels charge similar royalties but have widely varying initial application fees with many brands of Wyndham Destinations charging initial application fees of $2,500 and with other hotel chains charging upwards of $75,000.

That cash adds up. In franchise fees alone, Marriott brought in $1.6 billion in 2017, or $365,000 per franchised hotel. Marriott has more than doubled this number from the $697 million such fees raked in just six years ago. Hotels owned and operated by Marriott bring in similar fees totaling $1.709 billion, as the franchise occupies an ever greater share of the market and capitalizes on markets such as Asheville.

Remember, as a comparison, the hotel tax in Buncombe County is six percent on every room sale. Often royalty fees are second only to payroll expenses on a hotel’s books, pumping profits beyond the reaches of many Asheville residents, and certainly beyond the reach of those employed in hospitality.

Again, Buncombe County occupancy tax is six percent per room rented. Royalty fees on almost any licensed hotel: at least four percent, if not six percent, plus application fee, plus royalties on food and beverages. Who wins? Hoteliers and the billion dollar corporations who license to them.

Additionally, when hoteliers come bearing gifts, one should keep in mind the curses that follow close behind. To get Council’s support, Patel promised $500,000 (over five years) for the city’s affordable housing fund. That’s a fraction of a fraction of a fraction of the massive profits he’ll rake in, and will not come close to matching the damage done: the increase of property values in the area (making it more likely locals will be priced out), not to mention the traffic, and yet another set of low-paying service jobs. But by promising these funds Patel catered the “McKibbon standard” (a set of informal guidelines most of Council agreed to for passing hotels back in 2016, which encourages hoteliers to donate fairly small amounts to the housing fund) and his company quietly extended its grip on Asheville with the help of five brands of hotel conglomerates totaling more than $35 billion in annual revenue.

So, how many of Asheville’s hotels are licensed by Marriott? Nine and counting.

How many hotels are licensed by Radisson in Asheville? Four and counting.

Wyndham Destinations licenses seven Asheville area hotels.

Choice Hotels licenses a whopping fourteen hotels (and counting).

Other big names include Hilton (annual revenue $9.1 billion) which licenses nine hotels,

Intercontinental Hotels Group (annual revenue $1.8 billion) which licenses eight area hotels and many other national chains such as Best Western (two hotels locally, annual revenue $4 billion) have a foothold here too.

Seven corporations: 52 hotels. And with $453 million in lodging sales in Buncombe in 2017, count on royalties alone to pump millions upon millions of dollars into the hands of multi-national hotel companies, not to mention the millionaire developers profiting locally.

One hotelier, Patel, has ties to five of seven major hotel conglomerates. Patel and Sneeden are certainly not the only ones striking it big in a town which runs on cheap labor. Millionaire John McKibbon (whom the aforementioned standard is named after) is deep into Marriott brands, and wealthy developer Tony Fraga’s FIRC Group purchased the Haywood Park Hotel for $18.5 million and built the Cambria Hotel (a brand of Choice Hotels) next door for $24 million.

Profit-hungry hoteliers, both locally and nationally, are taking advantage of a literal smorgasbord, where unions don’t exist and lodging workers are 25 percent less likely to be making than a living wage in a state which prohibits local minimum wage ordinances. Defending their industry, the TDA misleadingly states that “Hotels employ only 5% of the people in Buncombe County who earn less than $12 per hour.”

However, given that the total number workers in Buncombe County is 123,896 and 4,812 of those workers work in lodging (3.9 percent of the local workforce), it is statistically likely that if you are working in lodging you are not making the bare minimum necessary to pay your bills in Asheville. These millionaires and their billionaire bosses are taking advantage of poor and working class people, especially exploiting people of color—- and with the apparent consent of a majority of Council.

How did we get here? How did Asheville fall so easily into the hands of national chains? How did the TDA get such political power? Aren’t we supposed to be different, special, and yes, weird? It seems, though, that Asheville’s equity concerns are not so far removed from its obsession with tourism, as the ever more entrenched “every town USA” corporate culture dedicated to catering to those with privilege and money slowly reveals itself.

Segregation for tourism

Since its official inception, tourism in Asheville has relied on the displacement of Black communities, especially to build an economy that catered to wealthy white locals and tourists. In Urban Renewal in Asheville, author Stephen Michael Nickloff describes the visions of city planners nearly a century ago, as Asheville invested in the boosting of real estate and the promotion of a tourist economy.

City planner John Nolen’s views were endorsed by many in city government when he centered both tourism and segregation in his famous three-point plan for Asheville’s future:

The first [point] dealt with land acquisition for public space and presented its use as a viable and justified approach to obtain the city’s goals. The second illustrated the economic possibilities of tourism and the movement to create Asheville as a major tourist destination. The third stressed the importance for the physical separation of black and white citizens.

Though even in the 1920s, planners were setting their attention on Southside, the 98 percent Black neighborhood just to the south of Downtown. The Great Depression (which provided a bleak demonstration of how fragile a tourism economy can be) and then World War II would delay these plans for at least three more decades.

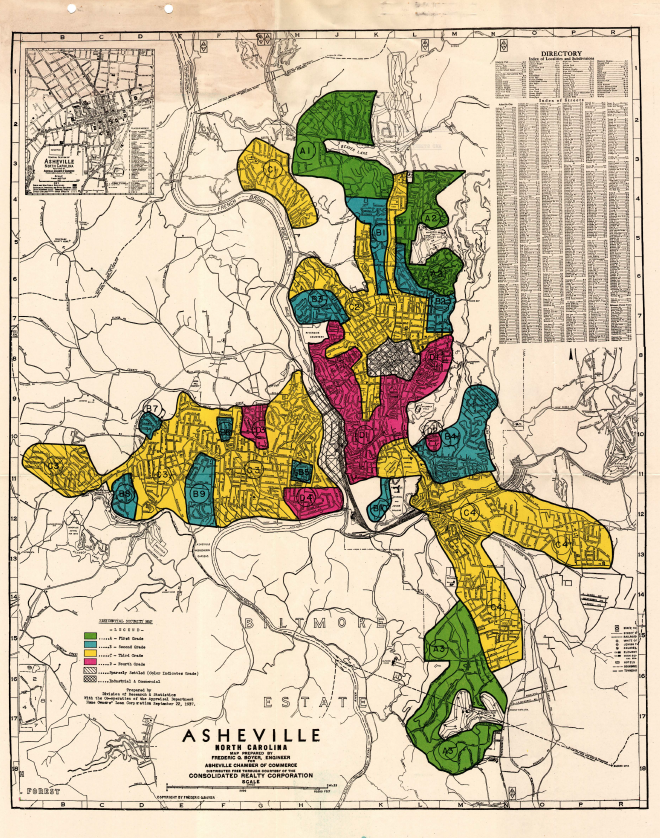

At the time Southside also held 50 percent of Asheville’s Black residents. By the late 1950s though, New Deal national programs and the redlining of Black neighborhoods they actively encouraged had already promoted the deterioration of a great many homes in Southside, as banks rejected loans because of residents’ race. Changes to laws governing “blighted” and condemned homes on the state and national level opened the door to planners eager to cash in on this land that had been coveted for decades, and kick out the tight-knit local communities already there.

The 1937 HOLC map of Asheville, part of the federal program that laid the groundwork for redlining. All but one of the areas marked in red are majority African-American

In March 1967 a city referendum for $7 million (adjusted for inflation) for “urban renewal” failed to garner the support of Asheville’s residents due to strong opposition from Black communities (the money from the national government for the projects adjusted for inflation was nearly half a billion dollars). However, after gaining the approval of the federal department of Housing and Urban Development, Asheville’s leaders placed a second referendum on the ballot that same year. After local gentry and city leaders convinced an alliance of some Black ministers to back the deal and blitzed communities with information in favor of the urban renewal project, the referendum passed that December.

The largest urban renewal project in the Southeast stripped Southside of “more than 1,100 homes, six beauty parlors, five barber shops, five filling stations, fourteen grocery stores, three laundromats, eight apartment houses, seven churches, three shoe shops, two cabinet shops, two auto body shops, one hotel, five funeral homes, one hospital, and three doctor’s offices.”

As can be expected, this project pushed out Asheville’s Black residents. In 1923, African-Americans calling Asheville home numbered 23,504 or a third of the city’s population. Today, more than 95 years later, that number is estimated by the Census to be around 11,028. This mass exodus defined, brutally, the shape of a segregated city for years to come. Entire families and communities were shoved out as real estate magnates and tourism enthusiasts made Asheville “attractive.”

Though John Nolen’s initial plans predated the TDA by about 60 years, the emphasis on shifting the local economy to tourism and the willingness to kick out whole communities to do it are the agency’s roots. It’s not a coincidence that the hotelier-run authority ramped up as urban renewal was winding down, clearing out what the white and wealthy viewed as “blighted” obstacles to their shiny new tourism industry. This disruption of community, still enforced by racism from multiple institutions, has shaped the worst achievement and discipline gaps in the state, shrunk the percentage of Black owned businesses to three percent, narrowed the annual median income to only $31,000, decreased the Black homeownership rate to 44.3 percent and increased Black Asheville’s portion of public housing residents to 70 percent. Asheville has horrific racial disparities in traffic stops/searches and charges of resisting arrest (exemplified by the beating of Johnnie Rush by Officer Chris Hickman). Our city, as it stands, shortens the lives of Black residents by 14 years.

And yet this shift in the city’s basic priorities (to segregation and tourism) wasn’t inevitable. In telling the tale of urban renewal Nickoloff explains the city’s seemingly dubious reason to shift all of its focus on tourism instead of another sector, manufacturing, which typically provides higher-paying jobs and relies less on displacement of residents:

In the mid 1960s, local officials and agencies credited the city’s manufacturing industry with salvaging Asheville’s economy and producing economic growth for the first time in thirty years. City officials and business leaders, however, believed a service-based economy and strong tourist industry offered more in the way of Asheville’s future economic growth and prosperity. Asheville’s decision to transition its manufacturing-based economy toward a service-based economy supported through tourism resulted from a position of want rather than a position of need. From this perspective, Asheville’s urban renewal represented a deliberate choice to effect profound changes to the city’s black neighborhoods in order to improve its physical appeal as a tourist destination.

Thus, the city intentionally decided to place tourism (and the subsequent displacement of Black Ashevillians) at the heart of its city planning. Decades later, they still do so.

As Asheville native, activist and longtime critic of the TDA Dee Williams states, “we should have been taking care of our own years ago.”

In comes the TDA

State statute created the Buncombe County Tourism Development Authority in 1983. According to the TDA’s own website: “Buncombe County hoteliers recognized the need to create a self-imposed tax that would ensure the region would not continue to see a drain of its visitors and the economic windfall they created each year.”

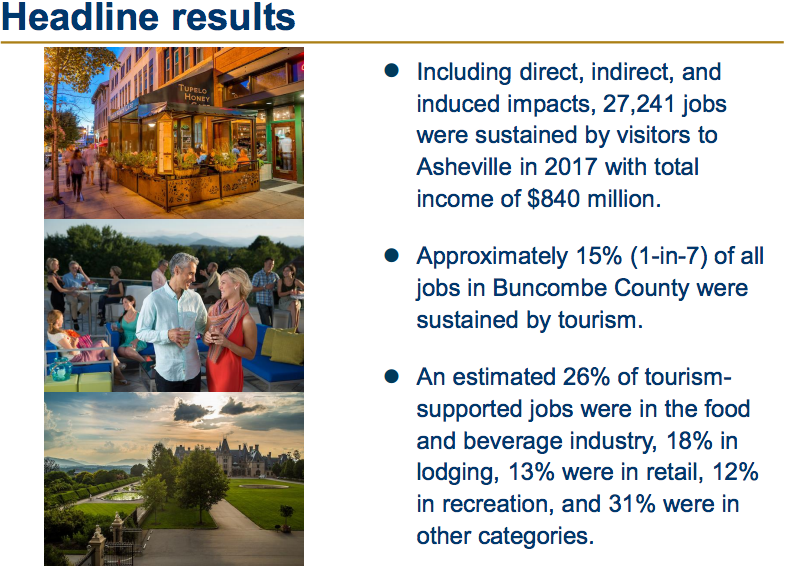

A slide from a 2018 TDA-commissioned report, touting the supposed benefits of tourism and marketing a white, wealthy Asheville

The kind of economic windfall and to which pockets profits are meant to flow are not subjects which are highlighted. The 11-member board containing hoteliers and zero elected leaders lists as follows: Jim Muth, Chair, Gary Froeba (Omni Grove Park Inn), Leah Ashburn, Andrew Celwyn, Chip Craig, Himanshu Karvir (Intercontinental Hotel Group’s Holiday Inn), John Luckett (Marriott’s Grand Bohemian Hotel), John McKibbon (Aloft, AC Hotels, and Courtyard – all Marriott), and Tom Ruff (Biltmore).

The hotels with voting power on the board in charge of $23 million in taxes local workers help to produce: Marriott, 2, Omni, 1, Intercontinental Hotel Group, 1, Biltmore Company, 1.

The Omni national brand of luxury hotels brings in annual revenue of around $2 billion according to Forbes. The Biltmore Company’s annual revenue exceeds $50 million.

Furthermore, the over $17 million the TDA directs towards advertising produces a an annual visitor to resident ratio of almost 15 to 1 and a ratio of 42 to 1 when considering all visits including day trips. That’s 256,088 residents in Buncombe County having to weather the impact of 11.1 million visitors annually.

Asheville Convention and Visitors’ Bureau, a division of the TDA, makes a point of touting the contributions to our local tax base, noting that sales and property taxes relieve the average Buncombe County tax payer of $1,800 per year. However, this tax relief is weighted differently depending on income. For those in the top one percent, the tax relief is far greater than the relief seen by Asheville’s poorest and most marginalized including and especially communities of color.

Additionally, in 1985 (two years following the creation of the TDA) average rent in Asheville was just $186, adjusting for inflation. In 2009, that number was an inflation-adjusted $910. In the decade since, that number has metastasized to $1234, while adjusted for inflation the minimum wage has only decreased 54 cents since 1985. Nonetheless, the BCTDA brags about Asheville tourism-impacted industries paying 16 percent more than the state average, while attempting to disguise the fact that working in lodging, a worker is 25 percent less likely to be earning a living wage ($13.65/hr) than in other Asheville/Buncombe County workplaces.

Moreover, the $27.9 million in additional property tax due to tourism eclipsed the Asheville Police Department budget by only $1 million in 2017. Notably, the site of the police beating of Johnnie Rush by Chris Hickman occurred mere blocks from both the recently approved Extended Stay and the Family Lodge hotels.

The “South Slope” is but one place in the city where it is dangerous to exist while Black. Poor and Working Class Communities and Communities of Color disproportionately bear the brunt of police violence, killings, mass incarceration, and the state of second-class citizenry which follows former felons for decades following release. Asheville has one of the highest numbers police per capita of any city in the state. Where gentrification and tourism go, policing follows, and the tourism boom has been used as an excuse to expand a police department with some of the worst racial disparities in the state. Its impacts are not felt evenly. While the tourists who come here are overwhelmingly white, the impact of Asheville’s policing disproportionately falls on those who aren’t.

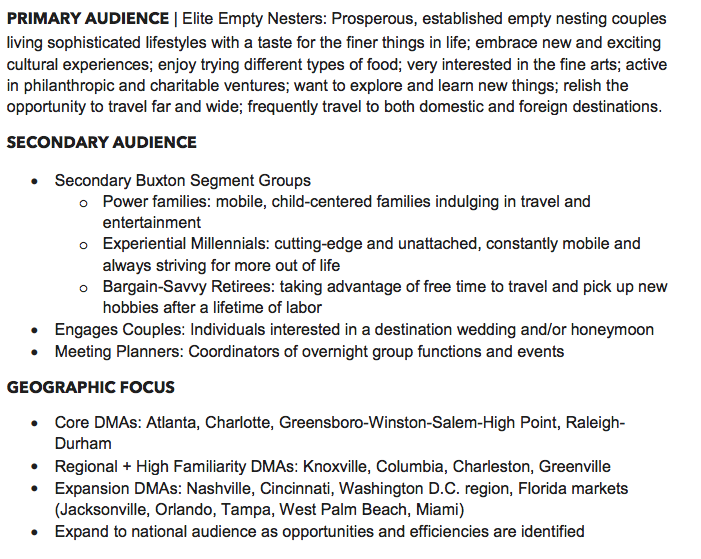

A revealing slide from a 2018 TDA marketing report, showing what demographics — and from where — they seek to bring to Asheville

The TDA’s 2017 annual report also features a slide describing visitor spending trends. Notably, from 2016-2017, Food and Beverage Sales in “Beer City” increased 4.7 percent to $543.9 million, Lodging increased 6.3 percent to $453.1 million, and AirBNB sales showed the highest increase of 15.4 percent to $4.4 million. The second highest increase was in the value of second homes in 2017. This is the amount spend on the upkeep of these homes, which increased to $90.4 million, an 11.4 percent increase. Meanwhile, an average of 20 people die every year in Asheville due to homelessness related health issues.

And as the Tourism Development Authority brings millions to the area, bringing millions of dollars in economic windfall (to a select few), according to its own presentation it focuses on two major demographics: Elite Empty Nesters and Power Families. “Elite Empty Nesters” are described as follows:

Prosperous, established empty nesting couples living sophisticated lifestyles with a taste for the finer things in life; embrace new and exciting cultural experiences; enjoy trying different types of food; very interested in the fine arts; active in philanthropic and charitable ventures; want to explore and learn new things; relish the opportunity to travel far and wide; frequently travel to both domestic and foreign destinations.

In other words, even the TDA itself admits that the wealthy (and overwhelmingly white) are their primary targeted demographic.

“Power Families” are an interesting sort, as well: “mobile, child-centered families indulging in travel and entertainment.” Also included are the demographics: “Experiential Millennials… Bargain-Savvy Retirees…Engaged Couples…[and] Meeting Planners”

Finally, the TDA also touts, “On a peak day in October, an estimated 25,000 overnight tourists visit Buncombe County while 45,000 non-resident workers commute into the city daily.”

As the tourists strain our roads at the tune of 11 million, so do our workers, making the daily trek to a city few can still afford.

Time to fight back

I’m a trans woman who moved to Asheville seeking relative safety and acceptance. Having started participating in Asheville as a white anti-racist activist with Asheville Showing Up for Racial Justice (ASURJ) the week before the killing of Jerry “Jai” Williams by Sgt. Tyler Radford on July 2, 2016. I entered a movement on fire. A march wound through the food court of Asheville Mall holding signs reading “Justice for Jerry” and “White Silence is Violence.”

On July 21, activists marched through the streets downtown and into the main police station, where seven (and two journalists) were arrested the next day. When a fellow activist left Asheville several months later and I sought to further my involvement, I was advised to volunteer for the Dee Williams campaign for city council in 2017. On the campaign trail, I would gain an introduction about the corrupt institution of the TDA (and the tens of millions over which it presides). On May 3, 2018, as news of the APD’s attack on an unarmed Black man still rocked the city, I found myself absorbing the scene at a TDA Board meeting.

I felt my skin crawl as Vice President of Marketing/ Deputy Director Marla Tambellini explained the some of the methods for spending those millions in occupancy taxes – on Google analytics and other online tracking softwares, in addition to ads cleverly inserted by anchors on the Weather Channel. She in fact framed TDA’s advertising as creepy four times: “It’s creepy and it’s gonna get creepier. Sit down and talk with me about it sometime.” They laughed.

Council member Julie Mayfield noted the closing of Asheville’s then largely self-inflicted $5 million budget gap in a tone that seemed nearly deferential to the assembled hoteliers (she didn’t have to say the police were receiving additional funds; this was implied). Having attended Council meetings several times over a year and a half, I had never seen her speak so meekly, eyes on the feet of the board members across the table from her.

This sense of discomfort only increased a month later when I attended a TDA meeting at the Explore Asheville Convention and Visitors Bureau, the building which hosts TDA and some of the most powerful of local figures every month. The Bureau is a division of the TDA, and Stephanie Pace-Brown its president.

I sat down and listened in as the meeting’s pitch increased in intensity. Before the crest, a Citizen-Times reporter sitting next to me gathered his laptop and his recorder, and left the meeting. I remained as board members responded to a CVB stakeholder survey which ranked “homelessness, transientness, and panhandling issues” eighth among 15 categories and launched into diatribes about the homeless, those who inject drugs and seemingly anyone who discouraged more “Elite Empty Nesters” from landing in Asheville high rises.

Pushing forward I-26, an interstate expansion poised to devastate the historically Black Burton Street neighborhood, which has already been partially dismantled due to past interstate construction, was an object of especial interest to Kit Cramer, the head of the Asheville Area Chamber of Commerce, and the recipient of a $300,000 yearly salary. I’d never seen the demands she leveled in any meeting, and in my bones, I understood the power in the room. The power of prestige, wealth, and the overwhelming thirst for more.

Some things said by at least of couple of our hoteliers and others who vote on this board:

“Who’s really homeless? It’s a drug issue. A needle exchange issue.” [Needle exchanges are actually part of a harm reduction strategy which prevents transmission of disease and saves lives among people who would use drugs anyway]

“Doesn’t make downtown a nice place to go. Just not a good situation.”

“Doing certain things that hurt you, make you concerned.”

“A lot of people downtown getting out of correctional facilities.”

Cramer mentioned giving police “all the tools we can,” encouraging opposition to the NAACP-proposed policing reforms locals were currently pushing for in an effort to at least reduce some of the APD’s enforcement disparities (then the worst of any city in the state).

An additional note: not even three months after these statements, harm reduction services provided by Steady Collective once per week out of Firestorm Books and Coffee and Firestorm itself would be targeted with notices of zoning violations for operating a “shelter.”

The Tourism Development Authority usually meets at 9 a.m. on the fourth Wednesday of each month at the explore Asheville Convention and Visitors Bureau, 27 College Place, behind the Iwanna Building, and provides a crucial glimpse of Asheville for anyone looking to bring it justice.

We have to fight back, and we have to heal. As Zev Friedman of Co-operate WNC puts it, “culture acts just like topsoil. And an act of violence takes a lot of time to reaccumulate.”

He and many in the cooperative movement are taking seriously the increasingly harmful wealth disparities, displacement of communities, and the crushing of small business economies. The cooperative movement is also highlighting the grim UN Climate Report, which gives us until 2030 to significantly curb climate emissions. Asheville is not directly in the path of most mega storms or rising sea levels, but the current stresses on infrastructure will only increase as millions visit (and stay).

Co-operate WNC believes that the creation of cooperatives take us back to our roots before lands, objects, and even people were sectioned off and assigned to wealthy individuals, before disasters such the enclosure movement and the birth of modern capitalism in 16th-century Western Europe.

Cooperative savings pools, cooperative businesses, cooperative land use (including forests), cooperative housing, healthcare, and more are tools cultures across the world are using to survive and thrive. In addition to building trustful relationships with neighbors and friends, cooperatives help resources and wealth remain inside the community instead of getting shipped out by the host of multi-national corporations (via royalties and fees on not just hotel rooms but across every area of our tourist economy).

Municipalities can play a key role. Madison, Wisconsin’s city government offers a things such as technical assistance and mini-grants to “worker cooperatives that address income inequality and racial disparities by creating living-wage and union jobs” through the Madison Cooperative Development Coalition.

While we build a new economy among friends and neighbors, it is imperative we push our elected leaders to end policies which harm our communities. As a white trans woman, I don’t face the racism my Black and Brown neighbors do, but the anti-trans bigotry that threatens my community has its roots in the same forces of bigotry, capitalism and patriarchy that seek to crush everything in their path.

Locally, City Council can withhold approval for hotels and mean it this time, showing that they intend to exercise their powers to dismiss hotels rather than rubber-stamp them. Our Council members must refuse to approve new developments that fail to provide significant amounts of deeply affordable units. Remember that if one had just adjusted for inflation over the past decades, rent would only be $186, or nearly seven times less than our current average rent, thus proving that deep affordability is hardly magical thinking.

Council must have no choice but to correct our Planning and Zoning Commission which has the authority to approve luxury developments that contain as many as 49 units, placing the survival of the many in front of the luxury of the few.

By showing up en masse, we might force Council to cut the police budget, refuse to provide high level staff pay increases and instead invest in the bus system, affordable housing developments controlled directly by tenants and other projects that support our diverse communities and stem the flow of our Black neighbors elsewhere.

These and other shifts could temper the effect of TDA’s biased and misleading messaging and put our county commission, which depends on Asheville for the majority of its members, on high alert. We might also coordinate with our county neighbors to push these exciting and much needed changes forward at county commission meetings, and in county elections.

Changing (or eliminating altogether) the hotel tax that predominantly funds the $17 million promotion of Asheville and associated exploitation is also incredibly important. North Carolina does not mandate counties fund a TDA through occupancy tax; it leaves the choice to do so (or not) to a local government. A majority of the Buncombe commissioners could choose to end the tax in its current form entirely, since the TDA has failed to serve the people, stopping the organization’s malign influence overnight. Nine counties across the state in fact have opted out of such arrangements. The list of counties which tax at half the rate of Buncombe is even larger.

Perhaps as a segue to some of these larger goals, we could instruct our commissioners to ensure that more Asheville and county residents living amid the effects of tourism hold voting power around the use of these funds. Marriott Corporation and the Intercontinental Hotel Group, as well as companies which built their wealth on slavery (The Biltmore Company) and $2 billion private companies (Omni) have outlived their usefulness.

It’s time is past when we made our worth and kept our homes.

Dee Williams, one of the several inspiring activists I have met while working here for justice notes that change will come from the bottom up. “Grow a movement and remove people who are in the way.” She also believes that change comes in part through bringing manufacturing back into the area, investing in living wage jobs, truly affordable housing, and local supply chains.

Perhaps it’s time for Asheville to jumpstart its own Green New Deal.

We who are advocating for greater checks on hoteliers, multi-national corporations, and those who market them do not wish for an abandonment of tourism altogether. Such an accusation is a false choice, used by those industries and their boosters to stop the rest of us asking questions. We simply ask for a diversified economy and for greater control over how our labor is used, how our tax dollars are spent and how the ecology of our region will be sustained. As so many of us came here from elsewhere ourselves, we will of course always welcome visitors to this beautiful region, which often markets itself.

Through cooperative business models and command of our economy, we will end the flow of wealth both outward and upward. Our right to home and health will not be compromised.

The topsoil, the culture of Asheville, in its many colors, will take years to regenerate. Let’s start now by demanding power over our city and the building a new economy where the rest of us have a chance to live.

—

Matilda Bliss is on the core team of Asheville Showing Up for Racial Justice, and also works with the Real Asheville Initiative, the Green Party, and Better Buses Together. When she isn’t petsitting or making schedules of events, she strives to live an off-the-grid lifestyle and creates jewelry from local stones

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by our readers. If you like what we do, donate directly to us on Patreon or make a one-time gift to support our work. Questions? Comments? Email us.