A recently-unveiled collection of photos reveals a new look at black and working class Asheville in the 20th century, and adds a major chapter to the city’s history

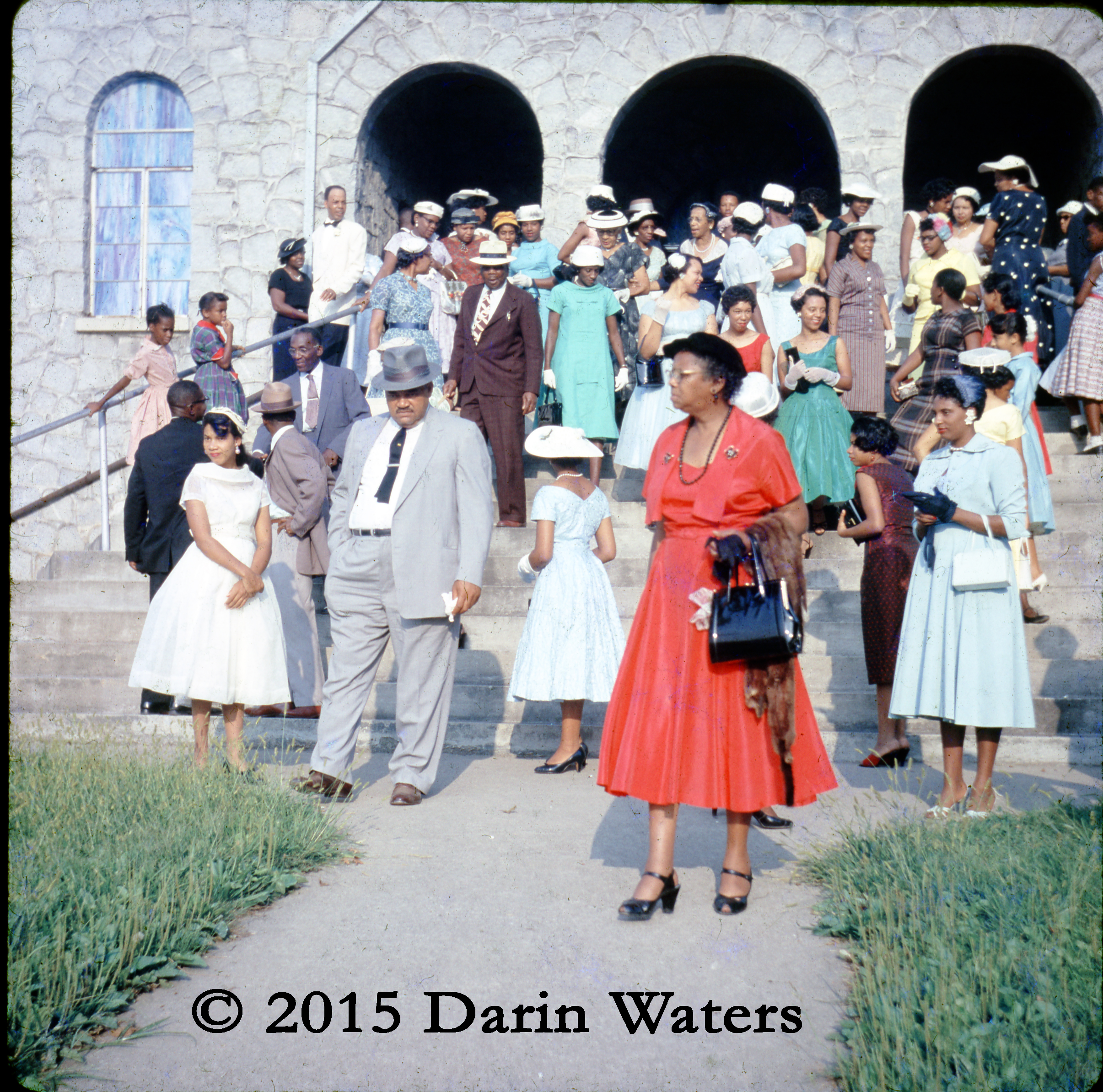

Above: Photo of an Asheville congregation. All photos from the Isaiah Rice collection, D.H. Ramsey UNCA Special Collection. Used with permission.

Isaiah Rice was many things: a community leader, a salesman, a pillar of the Burton Street neighborhood, a father.

He was also a photographer. Furthermore, Rice didn’t simply snap a few photos in his spare time; he knew his craft, researching and acquiring cutting edge photography equipment to capture the city and world around him.

“We stopped saying it was a hobby,” Darin Waters, a UNCA historian and Rice’s grandson, remembers.

Over the course of nearly three decades, from the ’50s until his death in 1980 he captured the life of the Asheville he knew, from major public events and disasters to locals going about their everyday business, in candid moments, after church or celebrating.

Starting earlier this year Waters started to work with other academics and librarians to digitize the images — Rice took thousands — in UNCA’s D.H. Ramsey Special Collections, which focuses on the history and culture of Asheville and WNC. The collection was unveiled at this year’s African-Americans in WNC conference.

Gene Hyde, who heads UNCA’s archives, was immediately impressed by the quality of the images.

“As we’ve been showing them to people we’ve heard again and again the term ‘professional quality,’” Hyde tells the Blade. “The quality of the equipment he used does not suggest he was an amateur.”

“I think he knew what he was doing: he was chronicling something,” Waters says. “That was the African-American experience in Asheville.”

“It’s rich with people and place, and how intertwined they are,” Hyde adds. “In Appalachian studies, we don’t often see this kind of photography from a ‘amateur.’”

“There’s photos of the family at home, photos of friends, people out in the street, just as you’d be in a neighborhood,” Hyde continues. “There are a lot of photos of downtown. His daily work life took him downtown and he often had his camera. There’s folks in their daily lives at his business that he clearly knew well.”

“It crosses the color line,” Waters adds. “You have white residents from Asheville in their home, I think it says a lot about his relationship with the larger community as well.”

“What’s revealed is how vibrant and alive the African-American middle-class was,” Hyde says of the “chasm” in the historical record Rice’s photos help to fill. “Largely when we view Appalachia in the 20th century we don’t think about the fact that there was a thriving, urban African-American middle class. That’s off the radar. This brings it up in beautiful detail with lots of humanity.”

During a panel on the Rice Collection during its unveiling, political science professor Ken Betsalel, who also helped collect the images, pointed out that many of the neighborhoods they took place in were considered “blighted” and that after looking at Rice’s photos, one had to question that designation.

“I’ve shown these photos to some of my Appalachian Studies colleagues,” Hyde says. “The overall impression is that this is a major change of perceptions.”

In photos of groups of people relaxing, getting married, working and more, Hyde says that “it shows how much a part of the larger fabric of Western North Carolina the African-American community was, that we don’t often think about.”

“One thing I see, in the photos of the students in Pritchard Park, is the dignity,” Waters says, even though they were still dealing with segregation.

“You have people in work and at play,” Hyde notes, adding that through his job and activity. Of 600 photos so far digitized, he notes, in only one does a person raise their hand to not be photographed.

Now Special Collections is seeking to identify many of the figures in the photos, asking the public to browse the collection, let them know people they recognize and help increase the knowledge of our city’s history.

“He was very active in his community, extremely active,” Waters said, especially in the Burton Street area. Rice was on the board of the Community Relations Council and was given a posthumous award by the Asheville Optimists Club.

“In so many photos people are looking at him like he’s a friend and colleague, not a stranger,” Hyde says.

More images below.

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by its readers. If you like our work, donate directly to us on Patreon. Questions? Comments? Email us.