The trial of a mutual aid medic ends in dismissal as supporters pack the courtroom and the cops’ case falls apart on the stand. Inside a major defeat for city hall’s war on community solidarity with the unhoused

Above: Local medic Greenleaf Clarke is attacked and arrested by Asheville police during the April 2021 raid on the Aston Park camp. Used with permission. Special to the Blade

Blade reporter Veronica Coit and editor David Forbes contributed to this piece

Rows of supporters escaped the summer heat, filtered through metal detectors, and took their seats on July 14 in a cavernous courtroom in the Buncombe County courthouse anticipation for a long awaited conclusion in the trial of Greenleaf Clarke, a mutual aid medic accused of assault during the infamous Aston Park camp raid of April 2021.

The crackdown on the camp, in a park at the epicenter of a particularly ugly wave of gentrification, was as brutal as it was calculated. A show of force that violated even Asheville police’s own policies, draconian in its own right, and a prelude to later crackdowns on houseless locals, protesters, and even two Blade journalists. Both of those journalists contributed to this report.

Asheville government and police counted on a conviction of Clarke on blatantly false charges of assault of a police officer, resisting arrest, and an openly absurd charge of larceny of a body camera that had been added on months after the original arrest date.

Police Capt. Mike Lamb even paused in his own anti-houseless tirade at a January council meeting even to brag about the district attorney’s office convincing Clarke’s two April camp codefendants to plead guilty.

The state had clearly hoped that Clarke would accept a similar deal, but as events unfolded on July 12 and 14 they would be bitterly disappointed. Those attending the trial, arriving at last after six continuances, witnessed Assistant District Attorney E. Blythe McCoy and two Asheville police officers scramble to convince Judge Julie Kepple they had a shred of a case. Clarke and eir attorney Hebekah Cannon, on the other hand dismantled the state’s charges relentlessly.

After a relentless assault on mutual aid the result was, in Cannon’s words, “a good clean win.” Here’s how city hall lost and solidarity won.

The ground we stand on

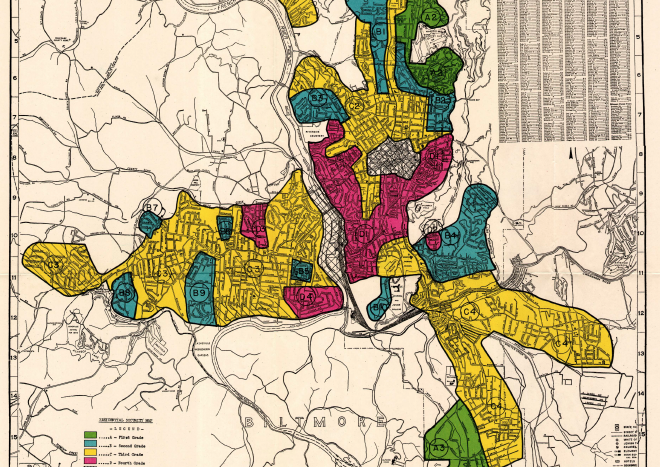

The 1937 HOLC map of Asheville, marking which areas were “unsafe” for housing loans. All but one of the areas marked in red were majority Black. Southside is roughly in the center of the map

“In the space of another year the traveler will see new, modern buildings, orderly green parks and newly-paved streets where once he saw an area blighted by age and neglect. What once was an eyesore will become one of the city’s top attractions…When completed, the project will be a show area for the city.”

– Jim Crawford of the Asheville Times, 1963. His article “Asheville Will Soon Put Her Best Face Forward,” soon printed by “urban renewal” proponents throughout the state, sold the destruction of Black neighborhoods as a boon for tourism

Aston Park lies in the South French Broad neighborhood, traditionally a part of Southside, a historically Black neighborhood making up the bulk of census tract 9. Before the urban renewal of the 1960s and 1970s, 98 percent of the neighborhood’s residents identified as Black.

As recently as 2010 the census tract remained largely Black, but just barely. For decades, gentrification had been hitting the tract hard, but the 2020 census uncovered a devastating reality. The tract lost nearly 500 Black residents and gained nearly 600 white ones, an enormous shift in Asheville’s Blackest district, which was now narrowly majority white.

Considering the many forms of segregation, including police brutality and economic deprivation, inflicted onto Black Ashevillians, it should surprise no one that 24 percent of Asheville’s houseless population is Black, a disproportionate number. Black locals make up about 10.5 percent of the city’s total population.

Leading up to the events at Aston in mid-April, 2021, Asheville government had been waging a war on houseless locals. City hall has spent years criminalizing houseless people, with numerous cops harassing single houseless individuals and engaging in warrantless searches at will.

In 2020, city staff waited months from the start of the pandemic to finally respond to an outpouring of calls, and finally set up hotel rooms for houseless locals. But these rooms were in the crumbling Red Roof Inn, on the edge of town, away from services and removed from the eyes of tourists.

Then, their disregard escalated in the shocking attack on the Lexington Ave camp during 7 degree windchill on the coldest night of the year, Feb. 1, 2021. The clearing was in response to a smattering of real estate agents and an attorney ranting about houseless people during a city council meeting and someone texting the city saying that houseless people should not exist within sight of “tourists and tax payers.”

However, more than 100 marched in solidarity with those houseless locals choosing to camp. Locals showing solidarity far exceeded those pushing social cleansing, but they weren’t the ones city hall cared to listen to.

As winter slowly subsided, the evictions continued. Some locals evicted from the camp on Cherry Street and other places reported that Asheville police directed them to Aston Park, which is city-owned.

That site is accessible to a plethora of services, including United Way, AHOPE, the transit station, the Buncombe Department of Health and Human Services, Western Carolina Rescue Ministries, and the Housing Authority case workers just south of the park. Mutual aid projects like Asheville Survival Program regularly offered resources in the park as well.

But gentry transplants in the area also regarded the park and its tennis courts as their personal property. Over the course of 2021 city hall would ramp up violent efforts to target camps and protest there.

The neighborhood is sadly no stranger to violence and displacement. The “urban renewal” of the 1960’s and 1970’s in Southside was the largest such project in the Southeast.

As chronicled by Steven Michael Nickoloff in Urban Renewal in Asheville, the effects were total devastation: stripping the neighborhood of “more than 1,100 homes, six beauty parlors, five barber shops, five filling stations, fourteen grocery stores, three laundromats, eight apartment houses, seven churches, three shoe shops, two cabinet shops, two auto body shops, one hotel, five funeral homes, one hospital, and three doctor’s offices.”

Today communities and scholars around the country study Asheville as an example of how utterly destructive urban renewal could be.

The city government at the time paternalistically claimed the changes were needed for the sake of “progress” and to address deteriorating housing conditions – conditions the very same officials helped inflict as a result of racist redlining policies. Other proponents, such as development consultant George Stephens said the quiet part out loud during a 1967 council meeting: “Tourists would make it a destination. They would not just ‘pass through’ Asheville. They couldn’t resist staying in the city we’re planning.”

Dissenting residents were numerous but often ignored by establishment media. Approximately 75 residents attended the final public hearing, but not a single one was quoted in the articles that were printed.

Residents would later speak to the true purpose of urban renewal, bluntly calling it “negro removal.” They described this act as a “top-down program that ignored the needs of the neighborhood, displaced and dismantled the community, and…made the area more attractive for outsiders.” Some things never change.

But before the April 16 raid on Aston Park houseless locals and the housed supporters whose presence they requested, shared in community.

Clarke was at the park as a street medic that day preparing salt water soaks to aid those with foot injuries. Ey saw this solidarity up close.

“I did get to witness the joy of watching people in song, and circles playing guitar together, enjoying each other’s company,” ey told the Blade. “There was a mobile kitchen, people cooking for each other. There was some bike repair happening. There was distribution of supplies, getting people camping supplies, getting people things they needed, including the medic work that I was engaged in. There had even been talk and action on securing some portable toilets for the camp.”

The sharing between houseless locals and those engaged in mutual aid brought flickers of euphoria for those participating, but it would not last. A few white gentrifiers in the neighborhood had the ear of city hall.

“This [was] both cause and effect of gentrification that day,” Clarke explained. Following the orders by a small group of city officials, the ensuing police violence would be “the result of many new white wealthy households in that neighborhood wanting to have their experience of this neighborhood match their idyllic expectations of a gentrified neighborhood.”

Ordered to clear the camp by the upper echelon of city government in a secret meeting that included the Mayor Esther Manheimer, Vice Mayor Sheneika Smith and City Manager Debra Campbell, the cops were on their way.

The police attack

“[Asheville police] used it as an opportunity to create violence where there wasn’t any and didn’t need to be any.”

– Greenleaf Clarke, on the April 2021 attack on Aston Park

Newer removals in Southside, and throughout Asheville, have taken the shape of Black-owned homes bought through shady schemes and turned for a profit by gentry land owners, airbnbs installed in the houses after renters were forced out and evictions of tenants whose stagnant wages never stood a chance in the face of greedy landlords and explosive gentrification. Newer removals have involved boots on doorsteps, the destruction of tents, arrests of occupants, and threats by people with badges, guns and the smuggest of smiles.

The removal of the Aston Park camp in April (and later in December) would be added to a list of removals that racist Asheville police would inflict at least 26 times in 2021, in the middle of a pandemic and eviction crisis that forced the growth of the houseless population by 21 percent. Houseless people of multiple racial identities were at Aston on April 16 when police launched a brutal eviction. A Black person who was pregnant and houseless was even arrested. City government, true to its form, brought incredible violence, but in the cloak of benevolence.

Mike Lamb in April 2021 telling unhoused people in Aston Park to leave or be forced out. Photo by Veronica Coit

First, led by Captain Mike Lamb, Asheville police arrived that morning with coffee and biscuits, but also, crucially, video cameras, guns, and tasers. The threat to leave the camp or face the violence of the state was clear.

Then, in the early afternoon Parks and Recreation Director Roderick Simmons — who announced his resignation the following month — covertly surveilled the camp. Clarke remembers that Simmons, his son, and the assistant Parks and Rec director arrived in plain clothes and mingled with those present without identifying themselves, taking advantage of a trusting community.

“It was such a sugarcoated way of interacting,” Clarke explained. “They tried to make friends with people and start off with a five minute conversation just shooting the shit, and then slipping in there little questions.”

“It didn’t come out initially that this was the parks and recreation director. When he arrived on scene, he was going around and just sitting down on blankets next to people, and starting conversations and, ‘Oh is that your tent?’ and things like that. He started to information gather.”

“He eventually came to some conclusions,” ey observed. Without consent, Simmons would begin to physically take down tents that were unclaimed. Clarke recounted how those at the camp would approach Simmons, asking him to “’please stop that, please don’t do this thing you’re doing.’”

Clarke observed police on site, including then-Lt. Brandon Moore (later promoted to Captain) would get in the faces of those objecting to Simmons’ actions saying things like, “’Are you threatening this man? Don’t you touch him!’” No one was even trying to touch Simmons, but the threat of arrest by Asheville police allowed the former director to continue tearing down people’s homes.

Late that afternoon, city government sent what Clarke would call a “battalion” of around 40 police officers (even more according to others on the scene). Even officers questioned why so many of them were unleashed onto Aston Park. Body camera footage played at trial showed one officer suggesting, “city council must have gotten an earful from the public.”

Yes, city hall received an earful, but not in the way that cop (who later quit) imagined. City records later obtained by the Blade and the Sunshine Request project show that Reuben DeJernette, McKenzie Brazil, and South French Broad “neighborhood association” head Helen Hyatt were the only Southside residents to contact city council requesting for the removal of the camp.

All of them are white, well-off and relatively new to the area, arriving less than a decade ago as part of a pattern of gentry transplants replacing Black residents forced out of the neighborhood. These three are the type of person Asheville government will literally bulldoze a camp – or a neighborhood – to please.

At least nine other locals contacted city government too, telling council to back off of the camp eviction. But in one of their illegal secret meetings the city manager, mayor and two conservative council members ignored them, choosing instead to listen to the handful of gentrifiers.

Body camera footage later presented at the trial shows the cops approaching Aston, discussing how they would criminalize those inhabiting the park. One dismissed the chances of convicting those present on trespassing charges. Another suggested that police “catch them in it.”

When she was told that the camp was cleared and four people arrested, Manheimer would pass on her personal thanks to “neighborhood association” leader Hyatt.

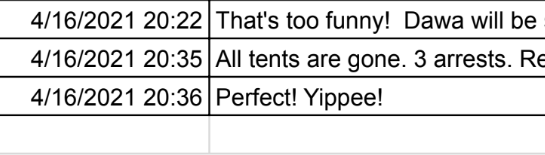

As Clarke and others were attacked, handcuffed and dragged off to jail, city manager Debra Campbell would greet the news by exclaiming “Perfect! Yippee!” in a text message to the police chief.

‘Fake medic’

“The state wants to have a monopoly on not just on violence, but authority, right? So if you’re not a state medic, you must be a fake medic. If you’re not a state journalist, you must be a fake journalist.”

“Whether we call ourselves anarchists, abolitionists, anti-statist, or simply people who give a shit about human rights, we are people who are reclaiming our collective ability to govern ourselves. We are reclaiming our collective ability to create our own systems of support networks, mutual aid…It’s in [the state’s] nature to want to dismiss that. It’s in their nature to want to discredit it.”

– Greenleaf Clarke, on being labeled a “fake medic” by an APD commander

The acts of painting protesters and mutual aid volunteers as “outside agitators” and leftist journalists as “participants” faking their identities are key tactics used by Asheville police and Asheville government looking to criminalize individuals and movements they don’t like.

Many of those facing criminalization in association with the December protests are trans or gender non-conforming. City hall likes to claim they’re trans-friendly, proclaiming their support of the rowdy anti-cop Stonewall uprising and passing a toothless “non-discrimination” measure. But they were happy to fall back upon the old transphobic tactic of saying “they are not who they say they are” in its effort to criminalize locals.

This was no different on the day that Clarke was arrested. Moore, a commanding officer, labeled Clarke a “fake medic,” body camera footage played at the trial would later reveal. Clarke’s medic pack was clearly displayed and video shows ey were attempting to deescalate the cops.

“[Moore] painted me as some outside aggressor who just came in to pick a fight,” explained Clarke of events depicted in body camera footage that was played for the court. “He called me like I was ‘guarding’, like ‘security’, things like that.”

Moore said Clarke’s demeanor in the body camera footage was an “aggressive stance,” but “it doesn’t match with what the rest of the court saw,” Clarke noted.

Clarke is, it’s worth remembering, a non-binary abolitionist who had previously spoken out against police violence at city council meetings, including for defunding the police department

“We have to ask ourselves, ‘Why did he see me that way?’” ey emphasize. “He had been targeting me. He had pointed me out to his subordinates 30 or 40 minutes before that.”

Clarke explained to the Blade the events that led up to officers dragging em away and charging em, without evidence, of assault on a government official.

“[S] was having a day of it because [they were] being displaced, but [they weren’t] in crisis until the cops showed up,” said Clarke of a Black houseless person on the scene who was pregnant at the time and who was being threatened by dozens of cops. While surrounded by the APD the houseless person, who will be referred to as ‘S’, picked up a screwdriver that was on the ground, but had not moved to strike or made any aggressive motion.

“[S]’s arm before that was down by their side. It was in a relaxed position,” said Clarke.

Clarke reports that the notoriously reactionary Capt. Jackie Stepp (who’s spearheaded APD efforts to ban busking and blame crime on an anarchist bookstore) then grabbed S’s arm, struggling for the object in a way that made it appear S was readying to strike Moore in the head. Clarke was in the midst of the crowd and was shoved.

City manager Debra Campbell exclaiming with glee after Clarke and others were arrested during the Aston Park raid

“I watched [Officer] Mazeika get hit by another officer in the back, and in the process of that, I also happened to get thrown around the same moment,” ey remember. “You have these cops with this implicit bias who have already pegged somebody as the enemy.”

Clarke would attempt to get out of the crowd, to evade the police violence already being inflicted on em, only to be brutally arrested moments after.

The defense committee for Greenleaf Clarke described what happened next in a July 11 statement:

“After being shoved and assaulted by a cop, Clarke was wrongfully accused of assault and tackled by multiple cops. While being detained, Clarke’s airway was temporarily cut off as eir face and neck were compressed into the grass. Ey were roughly wrist-locked while put in handcuffs, carried in a way that nearly dislocated eir shoulders, groped and searched for over 5 minutes, isolated into a mass arrest vehicle, and had eir seatbelt painfully tightened. Clarke was then subjected to gendered harassment and held for 7 hours before being released on bail.”

S would also be arrested, shackled to a hospital bed. Clarke explained: “Luckily [S] was released, but it took three days. [S] was redirected and from what we know was involuntarily committed for three days. That’s not where [S] wanted to be. That’s not what [they] said to us.”

The ‘larceny’ that didn’t exist

“They recognize that direct, physical violence does not play out well for community support. They recognize that they lost community support when they were doing violence in the light of day. Tear gas is one. Directly beating people, directly cracking skulls, directly severing arteries, things like that – especially when children are involved. They recognize how damning that was to their own image – this constructed, savioristic image that they’ve built for themselves. Where they’ve pivoted – I mean, they still do that, let’s be very clear that they still do that – is shifting a lot more of the violence out of the visible light of day. Into the shadows in the form of door knocks, in the form of waiting until days, weeks, months afterwards, people being picked up at work, people being picked up at their homes, on the side of the road for crimes they didn’t commit.”

– Clarke on some of the Asheville police tactics and violence ey survived

It became clear months later that Asheville police were unwilling to settle for bogus assault and resisting arrest charges against Clarke. On June 29, 2021 ey were harassed and arrested again, this time by Black Mountain police acting on a separate warrant filed by the APD just days before.

After dining in Black Mountain, Clarke realized that ey couldn’t leave in eir vehicle because town police blocked the exits to the parking lot.

Having no clue ey had an unserved warrant (filed six days earlier without notifying em), ey decided to film the cops as they used dogs to search another vehicle. Ey “wanted to make sure that the couple being dog searched would be okay,” but made the unfortunate choice this day to stand next to eir license plate. The BMPD retaliated by arresting em again. Ey were in jail for nine hours, this time on charges they stole a body camera and somehow hid it from police on April 16. Yes, the police actually claimed that.

According to Clarke, once ey were in the police vehicle, Black Mountain police called in the warrant and quipped, “This just goes to show that you don’t stick your nose where it doesn’t belong. And it’s a perfect example of mind your own business.”

“He was very smug that he ‘caught’ me,” Clarke said. While filming the police is totally legal, cops in general have a vicious hatred of being recorded, even to the point of their unions running national media campaigns and pushing laws to try to make people stop recording. Asheville police loathe “scrutiny from media,” according to a 2020 survey of feelings within the department. Video of police violence is exactly the kind of source we use to support our coverage. Footage of police violence literally saves lives.

Cops will occasionally run a license plate of someone recording them, even if, like in this case, the person has no way of leaving the premises and has committed no crime in their presence. The point is intimidation. The point is ensuring that the recording ceases.

Clarke’s close family and friends panicked when ey didn’t return home. Eir partner was even searching roads for Clarke before ey were allowed eir phone call from the jail hours later. It was an “extremely scary time for my family and loved ones.”

The warrant for eir arrest was filed more than two months after the alleged act. It was also completely made up: as soon as the trial began, the larceny charge was dropped due to a lack of evidence.

The trial

“Ultimately, we would treat every [houseless person] with dignity and respect…always had a principle of treating people with dignity and respect…Occasionally, we do have activists, anarchists, who refuse to leave and obstruct camp cleanup and tent removal… Thankfully, some of those cases were adjudicated, today, where the folks plead guilty.”

– Asheville police Capt. Mike Lamb lying during the Jan. 11 city council meeting

“Do you know how to answer ‘yes’ or ‘no’?”

— Judge Julie Kepple, demanding an answer to a basic question from APD Capt. Brandon Moore at Clarke’s July 14 trial

Asheville police and city hall, at a time when they are more hated than ever, have dedicated significant resources towards the criminalization of houseless locals and those who are in solidarity with them. In January, after proposing a ban on food sharing and smearing houseless locals as the source of Asheville’s crime, Capt. Mike Lamb lied about Asheville police department’s common practice of arresting the unhoused for trespassing. Records in fact show the department booked 29 locals on such charges from Dec. 26, 2021 – Feb. 20, 2022 alone.

When city council refused to push back on yet another brutal camp eviction, Asheville cops started arresting locals on absurd “felony littering” charges. City hall and the police department want to be seen as benevolent and servile by the white and well-off. If they can get away with it, they want to be seen as terrifying and unstoppable to everyone else.

The disappointment last month would be city government’s, however, as Clarke, eir legal team, defense committee and supporters showed up and proved that the APD was very vulnerable indeed.

The trial spanned two days but it was clear from the start that the state was clearly unprepared. Out of the four officers whose body cameras were submitted as evidence from that day, they could muster but two witnesses: police officer Mazeika and now-captain Moore.

Body camera footage was the only evidence presented by Assistant District Attorney McCoy. Perhaps a sign of how long the district attorney’s office dragged out the case and how fast the police department has been hemorrhaging officers, two cops involved in the April sweep no longer worked for the department by trial time. They were not subpoenaed to testify.

Cannon established crucially that Asheville police were acting on the city manager’s orders instead of calls for service alleging a specific crime, had failed to offer services to houseless locals and had attacked a camp that was breaking no law. Flatly, officers refused to follow their own manual, including their seven days notice policy on camp evictions.

“My legal team didn’t have to submit a single piece of evidence. We had evidence to support my innocence in these charges,” Clarke said. “Once we had seen discovery, we saw that every single piece of information we wanted to pull on was already there. The state did it to themself.”

McCoy scrambled for an angle to prosecute Clark. It was fifteen months after the arrest and she hadn’t even bothered to view the body camera footage. On the first day of trial the courtroom even witnessed Cannon reading McCoy the transcript of the footage. The obviously false larceny charge was quickly dropped on the basis of lack of evidence.

The dropping of the other charges would follow on July 14 when the trial resumed. Neither police witness could definitively say that Clarke struck Mazeika in the back. It was all hearsay. The warrant even contradicted the cops’ testimony, asserting that Mazeika had been struck on the arm instead.

The spectacle ran its course, but not before the assistant district attorney and the police officers repeatedly misgendered Clarke attempting to depict em as an aggressive man, also a common transphobic tactic.

The defense committee neatly summarized how Mazeika stumbled along during his testimony on the first day of trial:

“When asked what he was ‘doing there’ at Aston Park on the day in question, Mazeika changed his responses each time: first stating that he was ‘providing security’ for unhoused folx, then ‘to make sure everyone got along’, and lastly as an agent to assist in the removal of tents. It was an embarrassing spectacle for the state and made evident that the charges against Clarke are at best a waste of time and resources, and fully an act of state violence and repression.”

On day two of trial, the courtroom would witness Moore — one of the APD’s main commanders — fail even more miserably.

Moore tried to evade confirming that he used the words “fake medic” to describe Clarke, despite him clearly doing so in body camera footage. Kepple wasn’t having it.

“Do you know how to answer yes or no? You will answer this lawyer’s question,” demanded the judge.

“That’s when he deflated,” relayed Clarke, who observed Moore’s demeanor up close. “He started off with arrogance that was not there by the end of his testimony.”

The prosecution also attempted to portray Clarke’s hard gloves, seen in footage, as dangerous weapons. However, the gloves, often used while riding motorcycles to protect hands during accidents – and at protests to protect the user against police violence – weren’t even submitted as evidence.

This and the ways that Moore had clearly targeted Clarke, combined with the endless contradictory statements by the cops as to what actually occurred, put the prosecution in a tough spot.

McCoy even tried to bait Cannon into objecting to changing the warrant to reflect the shifting story by police, but Cannon was so far ahead, it didn’t matter.

“Nothing is clear in this case,” Kepple, said, delivering her verdict. She dismissed all charges due to a lack of evidence. Rows of Clarke’s supporters cheered.

At the end of the day, “this was low hanging fruit,” said Clarke.

‘They don’t have the power’

“We wanted to make it abundantly clear I was not alone.”

– Clarke, about the community support mobilized for eir trial

The conclusion of this trial is a real victory in a much larger war, a war waged against those who give a shit about their houseless neighbors, and a war waged by those who prioritize whitewashed “aesthetics” over people’s lives.

Dismissal of these charges will allow Clarke to move on with parts of eir life, but it does not erase the incredible violence ey experienced at the hands of the police. Sixteen locals still face blatantly false felony littering charges. Two Blade journalists face trespassing charges for monitoring the police. The social cleansing push from city hall is still going.

That said, “hopefully [the District Attorney reevaluates] some of the other cases,” as Cannon noted to those gathered following a sound defeat of an attempt to criminalize Clarke.

While this victory, by itself, doesn’t halt the war on the poor it inspires hope for what’s possible when these ridiculous charges are challenged and a community keeps showing up. The state is vulnerable, ironically often because of its own arrogance and incompetence.

Clarke and eir attorney took advantage during this trial, winning not just a dismissal of the charges against em, but also laid groundwork establishing Asheville police as violent instigators intentionally targeting the unhoused and those who support them.

The attorney established that officers chucked their own policies out the door to carry out the mayor and city manager’s orders.

“Knowing that we had this opportunity to clearly demonstrate our case and knowing that simultaneously, maybe, meet some of our political goals, that’s something we wanted to attempt and tackle,” explained Clarke. “We were trying to be really clear about APD’s breach of policy, their breach of humanitarian expectations, like what you should do for other beings.”

Clarke believes that the results vindicated the truth: “They do target mutual aid. They are blatantly fabricating charges.”

This was similarly true during the most recent park crackdown, where police violated their own camp eviction policy and kicked locals out of Aston before they could remove items such as banners and protest signs calling attention to the violence inflicted by city hall, pallets and bed posts used to break the wind for campers on cold winter nights.

“With the Aston Park defendants, we’ve seen people be terrorized, surveilled, and abducted by APD. They’re attempting to create this more panoptic state where ’they know if you’re naughty or nice, right’?” Clarke said, recalling the damage done by being abducted on a clearly bunk “larceny” charge months after eir initial arrest. “It’s effective. It scares people.”

“It’s really crucial for us to declare vehemently and with substance that [this] will not work,” ey continued. “We will not concede to that kind of fear tactic. They don’t have a panoptic gaze over us. They don’t have the ability to be everywhere at every time. They don’t know us.”

A grand jury, a tool of prosecutors, recently indicted all 16 defendants charged by police with ludicrous “felony littering” charges after the infamous Christmas raid.

A grand jury’s indictment can be arrived at by a simple majority as opposed to a unanimous decision required to convict. The juries do not accept evidence from the defendants, and indictments are only statements that sufficient evidence exists to hold trial. It’s more of a sign the D.A. supports the charging officers, as opposed to a failing defense. As the old saying goes, “a grand jury would indict a ham sandwich.”

“None of these charges should be trusted outright,” ey emphasize. “Cops lie. The court knows that cops lie, and we can establish that cops lie.”

Often, as eir trial showed, they lie badly.

Even with their $31 million budget the Asheville police are still down 40 percent of their active duty officers, and thus are even more outnumbered by the locals who hate them and wish them defunded and abolished. Remember, the vast majority of 1,148 voicemails left during city council’s first meeting during the summer 2020 uprisings called for the defunding of the police department.

Many backed the 50 percent defunding calls from the Black Asheville Demands collective, and they’ve kept doing so.

Remember the thousands that protested that summer, the hundreds that blocked the interstate on multiple occasions. The decorated racist monument that locals eventually forced a reluctant city hall to topple. The shattered the window of the mayor’s law office, “Defund the Police” in enormous letters in front of city hall.

As recently as council’s March budget retreat this year locals held signs and banners, including one that read “Sweep Esther,” and interrupted the meeting demanding sanctuary camping for houseless locals. Then defund advocates disrupted the June budget hearing shouting, “Defund APD, cops don’t need more money,” in an effort to halt the largest police budget increase in decades. Mayor Esther Manheimer, minutes after bragging how much locals loved the budget, sicced the cops on them.

Recently 700 protesters took to the street following the overturning of Roe v. Wade. Hundreds took the interstate that night as well. The cops could do little to stop them.

“They don’t have the power that they think they have. We have to know that they don’t have the power they think they have,” Clarke said.

Cannon addressed the group celebrating outside of the courthouse and its tall glass facade after their victory, emphasized “we are here today because Greenleaf was targeted for caring for their community.”

The multiple rows of supporters who turned out and showed they cared for Clarke reminded the courts and the gentrifying state that ey are a valuable member of eir community and are beloved by many.

Giving foot soaks and food in the park is mutual aid. This is too.

Just as each cop’s resignation is a sweet rain drop in a storm finally quelling a drought hundreds of years in the making, each victory in the courts is part of a much larger fight for our city. Time and again locals have fought — during a pandemic, no less — for everyone to have a safe place to call home. Time and again, locals have turned out for houseless residents and those organizing mutual aid. The trial was no different.

—

Matilda Bliss is a local writer, Blade reporter and activist. When she isn’t petsitting or making schedules of events, she strives to live an off-the-grid lifestyle and creates jewelry from local stones

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by our readers. If you like what we do, donate directly to us on Patreon or make a one-time gift to support our work. Questions? Comments? Email us.