Sweetheart deals for the wealthy pushed Asheville’s aging water system to the brink. Incompetence and arrogance shoved it over. This is the story of our city’s water crisis

Above: A tap in Candler, one of the areas hardest hit by the water crisis, runs dry. Special to the Blade

Blade reporter Matilda Bliss contributed to this piece

Starting on Christmas Eve locals across the Asheville area were plunged into catastrophe. Water stopped flowing, or came out brown when it came out at all. City officials — when they bothered to communicate — were unclear about who was without, who needed to boil their water, when the system would be repaired. Promise after promise broke and whole neighborhoods ran dry.

At the core of the system’s breakdown was this: for nearly two decades Asheville city hall has, repeatedly and deliberately, made the decision to charge big business obscenely low water rates. A working class Burton Street local pays more than twice as much for a gallon of city water as Raytheon, one of the largest arms dealers on the planet.

This has left the area’s residents with a worst of all worlds: paying gouging rates for increasingly poor service, but it let the wealthy get wealthier. Importantly the countless millions kept by hoteliers, major breweries and giant corporations didn’t go into upgrading and repairing Asheville’s ancient water system.

We are currently hearing city officials repeat ad nauseam that the disaster was “unprecedented,” caused by cold weather beyond their control.

This is a lie. Some of the same officials spouting this were the same ones who voted — despite repeated warnings — to keep gutting the water system to give the rich handouts. They were the ones who reacted to a similar 2019 breakdown by keeping everything the same.

Those choices were compounded by gross incompetence by city management that failed to prepare for frigid cold despite plenty of notice. On top of that a p.r. apparatus geared towards smearing minorities and deflecting blame was, not shockingly, totally unable to effectively alert the public.

This is the story of how corruption led to catastrophe, and how it will happen again unless city hall is stopped.

Rusted out

The strange story of Asheville’s water system goes back almost a century. In the late 1920s the patchwork of city and county water systems all went bankrupt in the nationwide financial crash. In the wake of that the systems consolidated and the state legislature passed the first of the Sullivan Acts, laws that forbid the city of Asheville from charging non-city residents increased rates. Other cities have generally used such powers to promote annexation and bring in additional revenue.

There was more: Asheville also was one of the few municipalities in the country that didn’t default on its debt, instead opting to spend decades paying it off. This kept downtown from being demolished but left local government cash-strapped for decades.

By the 1970s and ’80s a lack of repairs had led to widespread dysfunction, and water pouring down city streets (usually in Black neighborhoods, which took the brunt of infrastructural neglect) was not an uncommon sight. In 1981 Buncombe County and Asheville’s government formed a regional water authority, but were unable — and often unwilling — to tackle many of the system’s ongoing problems. In 1995 Henderson County joined the agreement, which involved constructing an additional plant at Mills River to aid the system’s flagging capacity.

The authority ended up mired in a fight between city officials and Henderson elites whose main priority was using Asheville’s water to fuel their own suburban expansion. In the summer of 2005 the agreement ended and Asheville city hall opted to take control of the water system. But they promptly ended up in a political brawl with Buncombe County officials and state legislators, who reaffirmed the Sullivan Acts.

This was followed by an attempt in the early 2010s by far-right state Rep. Tim Moffitt to seize the water system and turn it over to the Metropolitan Sewer District (and, almost certainly, eventually privatize it). Moffitt’s complaint was that the city’s rate policy, already heavily favorable to the wealthy, wasn’t even more corrupt. His push faced widespread public opposition and was broken entirely when a 2016 state Supreme Court ruling struck down the law it relied on.

The story that follows will go into countless catastrophic problems with Asheville’s management of the water system — especially the degree to which it’s favored the wealthy — but it’s important to remember that the previous authority was plenty awful and the Sullivan Acts are a blatant handout to suburban developers.

Multiple things can be bad at once. Asheville’s water problems are a stark reminder that no government gives a damn about the people here.

Over the years city officials have blamed the legacy of the regional authority and legislative power grabs for the system’s many problems. To be clear, these are all real issues. But the worst problems are thoroughly of their own making.

On paper Asheville should have an ideal water situation. Its main two reservoirs — the Bee Tree and North Fork — are pristine and well-protected, thanks to a hard fight by local environmentalists in the ’80s and ’90s. The area receives no shortage of rain.

While the Sullivan Acts deprived city government of revenue from new development they still controlled what water rates different types of uses and organizations were charged. If getting the cash to fix the system was truly the priority then local officials had plenty of power to do so. Yet after they took it over they again and again chose not to, even as tourism and development boomed.

In 2005 a conservative council decided on a rate structure that massively privileged big business. While “progressives” took over in that year’s elections they kept that basic structure intact, as has every single city administration since.

Even back then this was unusual. Many water systems around the country charge a uniform rate, meaning that all customers pay the same amount per unit of water. A 2006 Mountain Xpress article noted that a uniform rate would have cut costs for most residents by nearly a third by putting more of the burden on the wealthy. This was repeatedly raised to city officials, who refused to consider any changes.

A progressive water rate system, which many environmental advocates push for as a necessity in the face of climate change, would go even farther and charge big businesses a considerably higher rate than residents. Such a system would dramatically lessen the burden on locals, push businesses to conserve water and get far more cash to repair Asheville’s long-running problems.

Naturally city hall’s refused to even consider it.

What started as an unfair system in 2005 only got worse over the years. By the early 2010s Asheville residents were paying water rates 40 percent higher than the national average, while big businesses here were paying rates 20 percent lower. The more water an entity used, the more it strained the ancient system, the less it paid for every gallon it pumped.

Even the consultants city officials brought in to assess the system’s problems during those years thought it was a set-up far too favorable to the wealthy. Despite some minor shifts in water rates this has largely remained the case. Indeed in recent years, during city manager Debra Campbell’s openly classist tenure, Asheville city council has doubled down with repeated high rate hikes for residents only increasing the disparity.

The inequities in Asheville’s water rates‚ which are measured per one hundred cubic feet (about 748 gallons), are now staggering. For-profit healthcare giant HCA (annual revenue: $51.3 billion), for example, pays about half the rate local residents do.

Major manufacturers, like Raytheon (annual revenue: $56.5 billion) or Linamar (annual revenue: $5.7 billion) get an even bigger discount. A recently-hired public school teacher (annual revenue: about $35,000) pays more than twice what they do for a gallon of water.

About a year before the pandemic this corrupt shambles erupted in widespread disaster, as a line breach near Black Mountain led to brown water and a days-long boil advisory throughout much of downtown and West Asheville. That disaster also revealed stunningly incompetent communications from city hall, as they failed to use alert systems, put out contradictory messages and bristled when locals and journalists asked them basic questions.

After this Asheville city officials took a long look in the mirror and decided to change absolutely nothing. No one was fired for the communication blunders. Instead of being reprimanded top city management were effusively praised and given major raises.

That year Asheville averaged one boil water advisory a day somewhere along its lines. While a massive backlash finally led to overdue upgrades and repairs in some of the areas hit by the 2019 disaster, no fundamental changes were made.

Instead, as the pandemic hit the town and clean water became more essential than ever, officials turned their attention towards fancy new gadgets and draconian enforcement on already cash-strapped residents.

This is another aspect of the Asheville water system being a horror for most of the people that live here: not only do residents have to pay sky-high rates, they face draconian enforcement if they struggle to meet them. Many water systems around the country will give users an extended period of time to settle up a bill before shutting off water. Asheville’s will do so if payment’s overdue by as little as 15 days.

The system’s bill collectors are also notorious for refusing to take into account mitigating factors like a major water leak. In a town with an aging housing supply this can lead to massive bills that drive residents out of their homes.

In the fall of 2020, before vaccines were even available, city manager Debra Campbell (annual revenue: over $250,000 a year) insisted on resuming water shut-offs and repeatedly expressed an obsession with making cash-strapped locals pay their inflated bills. After public outrage shut-offs were again halted during 2021’s winter covid wave, but resumed that February.

Less than a month later city management announced plans to hike already-high water rates on residents more than 50 percent over the coming four years.

At council’s 2022 retreat they went further, announcing plans to continue those sharp increases. Much of this wouldn’t go to long-overdue repairs, but for “smart meters,” the kind of flashy change overpaid city staff like to have on their resumes to look like something’s being done.

This past summer council passed those rate hikes 6-1, with only council member Kim Roney offering any dissent.

In the early weeks of December water managers held a “tabletop exercise” disaster prep scenario, supposedly mapping out how the system might break. They went into the holiday season sure they had everything under control.

They were devastatingly wrong.

Breakdown

As Christmas approached cold weather was on the way. This wasn’t a surprise: it was forecast well in advance and Governor Roy Cooper declared a state of emergency on Dec. 20.

While the temperatures were very cold, dangerously so for those without shelter, they weren’t “unprecedented,” as city hall would later claim. Frigid winter weather is nothing new in Appalachia, after all. The temperature hovering near zero is certainly unusual, but it’s happened plenty of times before.

That kind of weather means that locals left taps on, just a bit, to prevent pipes from freezing, especially as the water system’s vicious enforcement means a burst pipe can push one out on the street. Indeed, as the cold front approached the public was repeatedly alerted to do exactly this.

That increases the impact on the water system, of course, as did the holidays, but that’s something it’s supposedly city management’s job to prepare for. They hadn’t. The intakes for the Mills River water plant, now needed to meet the increased demand, were frozen solid, “an ice-skating rink” as city water director David Melton would late put it in a city press conference.

Apparently in all their planning, the incredibly basic winter preparation of “make sure a key part of the water system’s back-up is properly heated” hadn’t come up. Multiple major line breaks — the direct result of years of city officials cutting discounts for the wealthy instead of fixing the system — made matters worse.

If city management had alerted the public to these issues on Dec. 24 locals could have started filling bathtubs and storing water to flush toilets. Instead they said nothing even as the situation kept spiraling out of control.

Instead over 48 hours passed before they reversed course, now insisting that locals needed to turn off their taps to save water. Some locals would say that they’re already been hit by intermittent water — or lost it entirely — before Christmas Day was even over.

At 12:30 p.m. on Dec. 26 the water department issued a terse note through city hall’s alert system:

NOTICE: The extremely low temperatures and high water demand continues to place an unusual strain on the City of Asheville’s water distribution system. Please consider conserving water and delaying unnecessary water use for the next 24-48 hours to help avoid low or no water pressure for all customers.

Just before midnight on Dec. 26 a boil water advisory went out for the whole southern portion of the system. By that time thousands of locals’ water was already sputtering out.

Around this time, according to an interview with Mayor Esther Manheimer by Asheville Watchdog, officials made the decision to “tie off” the southern part from the rest of the water system.

This was supposedly done to prevent a systemwide boil water advisory. But importantly it left water for the core of Asheville’s tourism industry — and wealthy neighborhoods like the one where the mayor lives — intact while cutting it off for thousands on the margins, including multiple rural working class areas, Black neighborhoods like Shiloh and Deaverview and Latinx communities in Candler.

Here the same communication breakdowns witnessed in the 2019 water disaster reared their head again: even many locals signed up for city hall’s alert system received no message. The Blade has, at this point, heard from over a dozen residents in areas impacted by the water crisis who never got these first alerts.

At the same time Candler residents also started to lose water or have it only come out intermittently. No alert was issued for their area.

By the morning of Dec. 27 the city’s water customer service line carried a systemwide alert, declaring “communication to all water customers: this is a boil water advisory.”

But much of its other media was pointedly silent. City government’s main website highlighted no emergency, and the its twitter account had been silent for nearly a full day. To even find the previous night’s boil advisory one had to dig through multiple layers of their website.

Part of this is because alerting the public is not the point of city hall’s communications. While they’ve always been notoriously incompetent, since the 2020 uprisings they shifted their focus. The result was a system focused around smearing protesters and the unhoused while doing damage control for city hall. The police department, for example, hired a notorious right-wing firm and threw its efforts into blaming Black communities for a non-existent rise in violent crime.

In 2021 city hall brought on Kim Miller, a former Fox News bureau chief, to be its p.r. point person. She’d play that role throughout much of the water crisis. Bluntly, informing locals about an actual disaster was not their priority.

Throughout that day people searched vainly for information. City hall’s last social media posts were bombarded by angry locals demanding to know what was going on.

At 12:33 p.m. p.r. official Christy Edwards finally sent out a press release, but it made no mention of any boil advisories and mostly contained vague “we’re working on it” boilerplate. City hall also declared “mandatory water conservation measures” (for residents, not businesses), including skipping laundry, taking shorter showers and not washing the dishes. No map was provided. Edwards even seemed unsure of what areas were hit by the disaster, declaring in the press release:

“The issues are focused mainly on the southern distribution area, but all other parts of the system could be affected with no water pressure, low water pressure and discolored water.”

Shortly after some locals received the following alert, asking them to click a link for more information about the water crisis. The link, naturally, did not exist.

Even after 2019’s breakdown officials had apparently no plan to get water to residents if a key, clearly vulnerable system failed. By early evening Dec. 27 they said they were working on it. They also claimed water would be restored in another day or two. It would be the first of many broken promises.

When the next morning rolled around three different parts of Asheville’s government carried three different answers: their customer service line still had a systemwide boil advisory, their website said only the Southern portion of the system was impacted and council member Kim Roney said only residents of specific areas that had received alerts (again, many with water issues hadn’t) should be concerned.

Later on the morning of Dec. 28 a release from Miller claimed city hall had water delivery service up and running, and locals could access it by calling 211.

But that was botched too, as 211 is an information and service connection line not geared towards this type of massive public effort. The fire department was supposed to handle water deliveries, but constrained the service to the elderly and disabled, leaving out the impoverished and immunocompromised.

Unstead of working around the clock to make up for lost time (thousands had already been without water for days) the city’s water delivery service only ran from 9 a.m. to 7 p.m. Eventually they’d shift it, to further confusion, away from 211 to the water department.

Not for the first time, where government floundered communities sprang into action. Locals talked directly about what happened to their neighborhoods, compared notes and shared information. As city hall’s water efforts floundered over the coming days local mutual aid groups like Asheville Survival Program and Asheville for Justice started setting up water pick-up sites in Shiloh and Candler.

In an announcement around noon that day city officials finally sketched out which areas were under a boil advisory. But they said the southern boil advisory area began around River Road, which doesn’t exist. They meant Swannanoa River Road.

At press conferences that day, the first of a bevy city officials would hold over the coming week, the focus was spin rather than aid. Manheimer claimed, wrongly, that only households that gotten an alert needed to boil their water, when it was already clear that the problems had spread over a large area. By that afternoon the boil advisories would be extended, belatedly, to the areas of Candler already hit by outages for days.

When asked if she’d reached out to local communities Manheimer instead said that she’d “talked to businesses.”

Meanwhile AFD Chief Scott Burnette would claim that most stores “were fully stocked” with bottled water, while local social media was already flooded with shots of rows of empty shelves.

When city downtown commission vice chair Andrew Fletcher messaged city manager Debra Campbell on Dec. 28, seeking more information he received a notice saying she was out of the office until Jan. 4. She was, however, available for photo ops around the same time.

It also hadn’t escaped the public’s notice that the “mandatory water measures” were all directed at hard-hit locals. City hall wasn’t shutting down or even forcing conservation on water-intensive businesses — like hotels, breweries and car washes — something well within the mayor’s powers given the declaration of emergency still in place.

At their pressers on Dec. 29 city officials shifted the goal posts again, now promising that water would be restored systemwide within 36 hours. They would break that promise too, and the one after it.

They also finally released an incredibly rudimentary image of the boil water advisory areas, after days of claiming they couldn’t due to made-up “privacy” concerns.

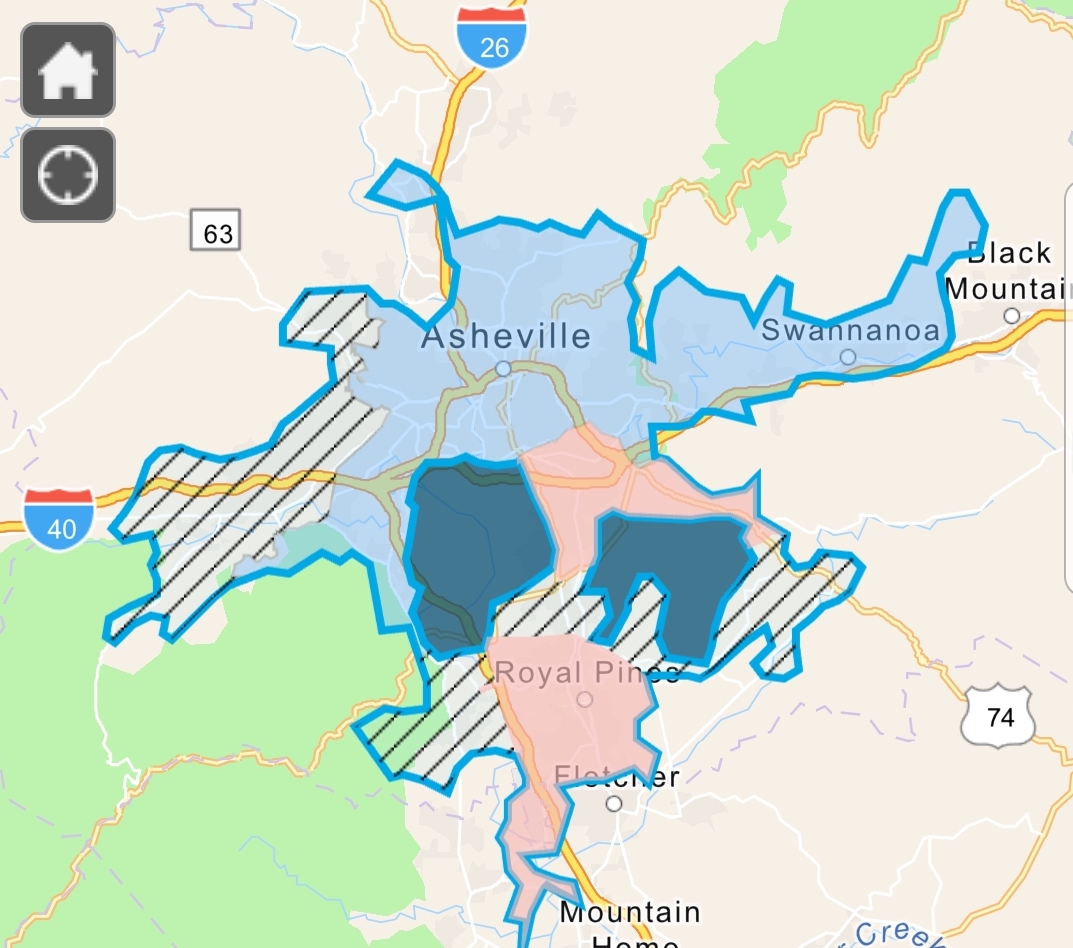

On Dec. 30 they finally released a somewhat more usable, interactive map of the boil water areas and where water was still out. But it often wasn’t accurate and remained rudimentary. Over the coming days neighborhoods it claimed had restored water would still go without, often being ignored by city staff despite repeated calls for help.

At these press conferences they started to hone their major excuse, that the water crisis was “entirely weather-related” in the water director’s words. Manheimer, who has apparently suffered a case of terrible amnesia since the 2019 water breakdowns, said it was “unprecedented.”

The water map finally released by city hall on Dec. 30. Hatched areas are without water, red areas were supposedly being restored though many residents say they weren’t for many days

Campbell, who has the most day-to-day power of any city official, gave the most tangled non-apology of them all.

“We are so disappointed our system disappointed people over the holiday,” she said on Dec. 31, of tens of thousands without a basic human need. “What I hope the community realizes is that if this situation could have been avoided, we would have avoided it.”

None of this is true. Years of city hall’s determination to favor the wealthy instead of fix the system made its lines vulnerable. Incompetent water system management failed to ensure the Mills River plant’s intakes didn’t freeze despite that being an obvious danger in cold weather. A cascade of communication blunders, entirely in local government’s hands, left the public with little or contradictory info.

They could have required water-intense businesses to scale back or shut down, but instead chose to tell locals to skip bathing. Emergency planners could have had a water delivery plan already in place, but they didn’t.

Asheville’s water crisis was, at every level, predictable and completely preventable. But the people of this area are simply not city hall’s priority. They do not care what happens to the vast majority of us. They acted like it.

The human toll

While officials made excuses nearly 40,000 people, at least, were left without water for well over a week before it was finally restored citywide nearly a week into January.

They were enraged.

“If this is your idea of being prepared I would hate to see what happens when you’re NOT prepared,” one local wrote on a city hall Facebook post in response to Melton’s absurd claim city water managers were ready for the crisis. Plenty of others (“eat glass”) were far less diplomatic. Some told stories of using their little available cash to buy water and still not having enough left to flush the toilet. By and large, city officials ignored them.

Amid this anger they were also struggling to make it through an ordeal.

As the new year started the city’s map touted more and more areas with water service return. But this was often false. Mutual aid volunteers working with the Shiloh community told The Final Straw radio program that neighborhood still had many without days after city hall claimed it had been restored.

On Jan. 3, three days after Fairview residents had supposedly gotten their water back, resident Kyle Bailey told the Blade that his Fairview Hills neighborhood was still dry, and that the water department had ignored their repeated calls for help.

“It has taken quite a toll on all of us,” Bailey wrote in an email interview with the Blade. “A few people have left their houses and are staying at friends/family.”

Graphic by jarondagan. Made in the wake of the city demanding ‘conservation measures’ from residents but not from businesses. Used with permission

“For over 9 days, there have been no working toilets or means to wash dishes,” Bailey continued. “We have reached out to the water department countless times.”

“This all seems to show how terrible and outdated our infrastructure is here,” Bailey said, something he attributes to Asheville city hall rubber-stamping development rather than updating key public services like the water system.

On Jan. 4, after the residents’ story was featured by the Blade, water was finally restored.

Jessie, a Candler resident, lives in one of the areas that was the last to have water restored — they tell the Blade that they went without for nine days — and has a medical condition that made the crisis worse.

“The messages that I got from the city were pretty vague,” they recall. “They said that the water had been restored, but if it was cloudy or brown, let it run and let them know, etc. I was drinking the water when it came on, and it wasn’t cloudy or brown, but I do know that other people in the area, next door neighbors, etc were still boiling theirs to be safe. So yeah, the lack of clarity also around it makes me really nervous.”

Indeed, multiple Candler residents sent the Blade videos and images of their water coming out cloudy long after it was restored.

Particularly unhelpful to Jessie was that city hall’s information to the public were written in “that kind of governmental lingo where we’re going to say things that kind of aren’t going to be incriminating in any way, but aren’t really helpful.”

“It said, ‘It will be on in two days,’ and then it wasn’t. ‘It will be on in three days,’ and then it wasn’t. It kind of kept getting pushed back,” meanwhile “walking up and down the hill with watering cans and lugging five gallons from other parts of town; it’s pretty tiring.”

They say that friends in other areas of town helped them get water, and that their local neighborhood banded together to meet the crisis.

“My neighbor right across the street who has kids, young kids, she was bringing these five gallon containers,” Jessie recalls. “The only reason I have this one is because she dropped it off for me, which is really sweet. I didn’t even ask. But she works at like a health clinic, so she was bringing water and filling it up while she was at work and then bringing it home and bringing some for neighbors.”

They found that a nearby water station set up by Asheville Survival Program was particularly helpful to their neighborhood.

“There was definitely a sense of people were trying to help each other out. The community response was very sweet that I saw and very efficient,” Jessie said. “But it sucks that that has to be the case because really it was like a few individuals who were also dealing with their own water being out who were trying to help each other.”

But they and their community witnessed “no help from the government, of course, and no help from any kind of official sources to provide drinkable water or anything — most of the help that I saw being given and that I received was just from neighbors and groups like ASP.”

Despite this aid, some in their community had to leave to stay with relatives and neighbors in other parts of the area.

Just after water finally came back on in Candler, Asheville city council finally gathered to discuss the issue. But they did so in secret “check-in” meetings they’ve long used to make policy out of public view, in violation of open meetings law.

Echoing many locals the Blade has spoken to during the water crisis, Jessie thinks it’s telling that some of the least wealthy areas bore the brunt of the disaster.

“I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the areas that were the last to get their water back is where a lot of the public housing is, a lot of the poorer areas, a lot of the immigrants where there are a lot of the mobile homes. Because it was us and Shiloh that were last. And as far as I can tell, those are like the least gentrified parts of town.”

Stay angry

Image by jarondagan, based on the infamous 2020 photo of Asheville police destroying water supplies at a medic station

Tonight is the first Asheville City Council meeting since the water crisis. Locals are, rightfully, still enraged. Doubtless that will show up in many ways and many places.

Like the blatant abuses of the police department in summer 2020 (and many, many times before) the water crisis has attracted such public anger because it hurts so many people. At the same time it offers a crystal-clear reminder of the incompetence and callous entitlement at the heart of city government.

On Jan. 3 Asheville city council announced that they would form — what else? — a committee to study the crisis and recommend what might be changed. At the same time they’re spouting a chorus of “not our fault” every time they open their mouths.

If this feels like deja vu that’s because it is. They are using the same playbook they used in 2020 (and many, many times before). Combined with their many excuses city hall is committed deep down, to changing nothing. Publicly not a single council member did more than offer mild statements of concern and echo official talking points during the entire crisis.

So I have to end this article with a note to every community harmed by this crisis and looking to do something about it. I’ve covered Asheville city government for nearly two decades. They are your enemies and they have three major tactics: deflect/delay, co-opt and open repression.

As we’ve seen above delay and deflect have already started, with officials blaming the water crisis solely on the weather when the it was caused by their own incompetence, arrogance and nearly 20 years of letting the system crumble by charging big business ridiculously low water fees.

The committee proposal is also part of this. City government committees are a joke. Their purpose isn’t actually to change anything, it’s to bury change and delay/deflect public outrage by promising that a “committee’s working on it.” If by some chance the committee proposes any actual changes city officials will ignore them, as they did with previous boards on issues like equity, human rights and transit.

Ironically the local far-right is helping city hall’s deflection by blaming the water crisis on local governments supposedly pouring millions into reparations and removing the Vance monument. This is racist garbage, and false. Asheville city government didn’t even want to remove that segregationist hunk of rock until the public forced their hand. They have spent a minimal amount on “reparations,” mostly on outside consultants. They’ve repeatedly declared that Black communities will not get land or direct cash (so, no actual reparations). Plenty of Black locals have, from the start, accurately tagged the “reparations” effort as a p.r. stunt and nothing more.

All the things Asheville’s government is actually pouring cash into to the detriment of the water system, like cops and handouts to the wealthy, are all things the far-right likes and wants even more of.

The way around Asheville gov’s delay and deflection tactics is to refuse to play along with them. Ignore the committee idea. If you’re going to meetings make them miserable for the officials who show up. Openly laugh at their excuses. Any way you can, prevent them from pretending everything’s moving along in a nice and orderly fashion.

One of the things that really scares city hall about the public’s response to the water crisis is that people aren’t buying their spin, are directly talking about their own experiences and are not holding back their anger. Keep doing that. If they don’t like it they can always quit.

Indeed, if anyone in city hall was actually sorry about the water crisis the mayor, city manager, water director and literally every p.r. hack would already be out the door. They aren’t? Help make staying in office as awful for them as they made everyone who was stuck without water for nine days.

Bring up, constantly, that Raytheon pays less than half what a school teacher does for a gallon of city water.

When delay and deflection don’t work, officials will shift to co-option. When they do this they lean hard on their friends in the non-profit complex. So expect more establishment organizations to put together stage-managed forums focused on water crisis “solutions” (i.e. keeping everything the same and ensuring no one responsible faces any consequences).

They will try to split off some of an enraged public into long processes that the establishment controls and that accomplish absolutely nothing. Ignore them. If a well-paid official “organizer” suddenly shows up at your meeting to tell you how to do things tell them to leave. If this town’s non-profit complex solved anything Asheville wouldn’t be one of the least livable places in the country.

You and your neighbors’ justified anger at what was done to your communities is a surer guide to what to do than anything out of a workshop or seminar. Insist on organizing and deciding on action yourselves, outside of city government and outside of established groups. If demands are something you choose to focus on they need to be things that will actually disrupt these systems, like mass firings, ending water shutoffs and major hikes to water fees on big business while massively lowering them for residents.

If co-option doesn’t work city government will turn to repression. When people get angry at a council meeting, for example, expect the mayor to invoke some made-up rules of decorum (“no clapping” is her favorite, only ever applied to those who criticize her) and demand compliance. Locals will then be threatened with arrest for not following the b.s. rules the mayor made up.

So do the opposite of what they say. If they say don’t clap; do. If they demand silence, be loud. They don’t have the cops to arrest a crowd and they don’t want the headlines.

Outside of Asheville city meetings, expect officials to threaten any independent organizing around the water crisis. They’ve done it before with those helping defend the unhoused and even Blade journalists who covered them.

But they are, like every government, far weaker than they pretend. Remember about a year ago when officials wanted to ban food aid? That was stopped in its tracks because people refused to play city hall’s games, got angry and didn’t back down.

If things stay the same it will only be a matter of time until we’re once again stuck with undrinkable water, or none at all.

The nice way always fails. Rage and determination work.

—

Blade editor David Forbes has been a journalist in Asheville for over 15 years. She writes about history, life and, of course, fighting city hall. They live in downtown, where they drink too much tea and scheme for anarchy.

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by our readers. If you like what we do, donate directly to us on Patreon or make a one-time gift to support our work. Questions? Comments? Email us.