Asheville police and a right-wing pr firm unleashed a wave of propaganda falsely portraying the city as overrun by violent crime. Overwhelmingly, they targeted Black people

Graphic by Orion Solstice. Quotes are taken from Colepro marketing material as well as APD press releases and emails

Blade reporter Matilda Bliss contributed to this piece

Last year Asheville, like many cities, saw a historic uprising against white supremacy. Multiracial crowds called for an end to the city’s racist status quo, including for defunding the Asheville Police Department. They were met by crackdowns so vicious they made international news.

In the aftermath, city officials and a compliant press grabbed headlines with a supposed “historic” move towards equity. But even as council was waxing rhapsodic about reparations (while their cops kept beating up protesters) Colepro Media, a right-wing media firm and the APD ramped up a very different effort.

Like most police departments the APD sends out press releases. While certainly not averse to using these for racist propaganda in the past, as last summer wound on there was a noticeable escalation. Suddenly inboxes of local journalists and organizations were flooded with a barrage of announcements, many emphasizing drug arrests and a supposed wave of violent crime.

They disproportionately targeted Black people and neighborhoods.

At first this may not seem like much given the sheer scale of the APD’s racism in areas ranging from traffic enforcement to pulling guns on Black locals. But such releases form a major part of the local news narrative; they’re often repeated nearly verbatim by establishment media. City officials have regularly invoked talking points from them when refusing the growing push for defunding or backing more guns and facilities for police. Gullible columnists have swallowed the narrative they portrayed to dub any demand for an end to racist policing as “ridiculous.”

At the same time, the APD’s press releases consistently downplayed violence committed by white people or ignored it entirely.

As a longtime journalist in this town the shift was notable. While the uprisings continued the APD went from occasional alerts to a wave of press releases out of the 80s and 90s phase of the drug war, photos of Black men alongside shots of tables with confiscated drugs and a pistol, with some cash fanned out to make it look more impressive.

Notably the APD also started linking specific incidents to supposed larger crime wave, adding misleading tallies about gun violence to the end of certain press releases or claiming the latest arrests was due to “neighborhood concerns” about drugs and violence supposedly run amok in a specific area.

These tactics — using myths about “Black on Black crime” to shift attention from police’s abuses — are directly out of the far-right playbook, and marked a notable contrast with the supposed emphasis on equity coming from city hall.

They were also intentional. Through a close examination of a trove of city government emails the Blade discovered that in late July 2020 police chief David Zack, APD pr staff and ColePro consultants held a series of meetings honing talking points emphasizing “the racial disparities in crime.” They didn’t mean the disparities in the APD’s own enforcement; they meant emphasizing criminal charges against Black locals as a way to justify the department’s draconian presence in their communities.

They intended this — along with an array of social media posts intending to make the APD look good — as a deliberate strategy to take attention away from the “naysayers,” the thousands of locals then condemning racist police violence. Over the ensuing months announcements bombarded the public with reports of gunshots and arrests for possession of drugs and guns. At the same time they comparatively downplayed violence committed by white suspects.

The Blade analyzed every APD press release from the start of the uprisings until the middle of last month. We looked at the type of charges they involved, the demographics of the individuals they featured, the neighborhoods they targeted and which of the alerts the police tried to tie to a supposed larger crime wave.

The numbers are revealing. Leaving out minor administrative announcements the APD cranked out 277 press releases during that time. Over half — 52.3 percent — directly targeted Black individuals or predominantly Black neighborhoods. When a handful of press releases that targeted multiple individuals of different races and ethnicities are added in, 54.1 percent of the department’s pr targeted Black people in some way.

During the same time 99 of the APD’s press releases linked an incident to a supposed larger problem with crime. Of those, a stunning 82 percent targeted Black locals or neighborhoods.

Just over 11 percent of Asheville’s population is Black.

Delving down further the propaganda campaign becomes even more clear. Drug and gun arrests in Black neighborhoods were prominently featured, while violence done by white suspects was downplayed or ignored entirely. In 22 alerts the department dubbed incidents a “shooting” even though no one was shot, creating the impression gun violence was far more prevalent and deadly than it actually was. The pace and type of alerts also escalated considerably when city council was deliberating on the police budget and trying to fend off a serious push for defunding.

The reality, as even mainstream publications have started to grudgingly admit, is that violent crime declined during 2020. In 2021 Asheville, by the APD’s own numbers, has seen violent crime stay relatively flat or even decline slightly compared to last year, when people were regularly staying home to avoid covid.

This happened while the APD lost over a third of their patrol officers due to public defiance, though they’ve made a point of keeping up their violence directed at Black and houseless people. If anything the reality is a defense of what Black abolitionists have been shouting for years: that communities are safer with less cops.

As Grits, a local who’s confronted city council about their refusal to divest from the police department, tells the Blade, “it’s ridiculous to think that gun violence and violent crime can be solved by a violent force going in and trying to intimidate peace into people.”

While Asheville — like every other city — certainly does have real, tragic issues of violence, they are not unique to Black communities and police are clearly not any sort of solution. The thinning of their ranks has not made things worse than they were before.

Looming behind the APD’s propaganda barrage all is an ugly, but clear message: that Asheville is a dangerous city because of violent Black people and neighborhoods, that the department should get any money and power it wants to “solve” the problem, and that any action it takes in those neighborhoods shouldn’t be questioned.

It is, in short, the same old racist lie.

The Stats

The APD has used propaganda plenty before. When facing widespread opposition to creating a downtown policing unit, then-chief Tammy Hooper regularly used racist dogwhistles and pitched manipulated crime stats to gentry neighborhood groups (council, naturally, gave her what she wanted). After police murdered Jerry “Jai” Williams in 2016 the APD quickly spun a narrative trying to blame him for his own murder and distract from their brutal crackdown on those demonstrating against the violence that killed him.

In trying to halt even incredibly modest NAACP-backed reforms in 2018, local police association officials stereotyped Black neighborhoods as unhealthy and crime-ridden.

When public outrage finally forced council to adopt those changes, police officials and upper city staff simply refused to carry them out, shifting to boosting the talking points of far-right “concerned citizens.”

But the latest shift presents a significant escalation on the police pr front. This wasn’t the APD’s usual tactics of budget time propaganda or a single press conference trying to spin a particular atrocity. It was a change in the entire way the APD pushed talking points. day in and day out.

On the surface the pr was still coming from the same people as before, mostly longtime police flack Christina Hallingse, with the occasional release from staffer Lindsay Regner.

Behind the scenes, however, another party was playing a major role.

ColePro media, a right-wing pr firm that brags about its ability to help police departments “outsmart reporters” involved with city government since early 2020, escalated its in the wake of the uprisings. Among their duties were helping with “news releases, social media posts, talking points and press questions.” The change was notable. Last June, as the uprisings were starting, the APD did just 10 press releases the entire month. That August, when Colepro received a lucrative city contract for ongoing work, they released 31, amounting to one a day.

The sheer numbers and percentages are fairly staggering, as is who they targeted. During the time period examined by the Blade, the APD put out 277 press releases.

Over half — 52.3 percent — specifically targeted Black individuals or predominantly Black neighborhoods. When you add in a handful of releases that targeted people of different races and ethnicities, 54.1% of the releases targeted Black people.

Considering just over a tenth of Asheville’s population is Black, this is wildly disproportionate.

There’s more. Missing person alerts are overwhelmingly issued for white missing persons, a problem nationwide. And indeed, of those releases 26 were missing person reports, 20 of them for white people.

Leaving those out one is left with APD alerts about supposed criminal activity. The disparities only rise, with 57.3 percent targeting Black individuals or neighborhoods in some way.

But the cops didn’t stop there. All of a sudden press releases tied individual incidents to supposed larger crime waves sweeping the city, a practice they continue today. Here’s one example, from April 9 of this year:

“Since January 1, 2021, the Asheville Police Department (APD) has responded to 147 calls for service for a shooting. In addition, 5 people in Asheville have been shot this year.”

This particular example also showed how the APD was calling every single report of gunshots fired a “shooting” even when no one was shot.

In other cases APD announcements would mention that a specific arrest had been made due to “neighborhood concerns” about violence in a particular community.

Where, and to whom, did they direct this? Well a stunning 82 percent of the time these announcements targeted Black locals and neighborhoods.

Most of the alerts weren’t about people injured or killed. Their two highest categories were arrests for possession of guns and drugs and shots fired incidents (where gun shots were reported or casings were found but no one was injured). While Asheville’s notorious for issues with domestic violence — problems that only escalate during a pandemic — only six of the press releases focused on it. The APD issued more press releases smearing protesters than focusing on child abuse and domestic violence.

In 22 alerts the APD referred to incidents as a “shooting” even though no one was shot. In some press releases, like the one quoted above, they even started referring to every report of a shot fired as a shooting.

In recent months even establishment media and the police chief have been grudgingly forced to admit that according to the government’s own numbers crime has stayed largely flat while a third of the APD’s officers have left.

Now the usual racist dodge, which the APD decided to lean heavily on last summer, was that the APD’s simply focusing on Black neighborhoods because that’s where the violence supposedly is. This is untrue, of course. The APD decides which neighborhoods to occupy — Black men are overwhelmingly more likely to be pulled over, searched and arrested for things that a white tourist would get away with — and who to target. The largest predictor for getting charged with a crime, anywhere, is poverty.

The APD also plays a role in manipulating where calls for service come from. For years they and other city officials have held private meetings with business owners, the far-right and local gentry, encouraging them to call in any behavior they find suspicious — even if it’s not illegal — to boost calls for service in an area as an excuse for more police crackdowns. The Asheville Free Press recently reported that this practice hasn’t stopped.

But a basic examination of their press releases throws even more cold water on this old lie. In numerous cases APD pr downplayed violence — including gun violence — committed by white people. In others they ignored it entirely.

A number of examples stand out.

On June 22 Jerry Williams’ surviving family led a protest against the policing status quo that included locals painting a giant “defund the police” mural in front of city hall. That night, the far-right showed up — many of them openly armed. This included those local antifascists later identified as literal klan members. They were breaking the law by doing this: in North Carolina it’s illegal to carry a firearm at a protest.

Not only did the APD not arrest the far-right harassers, they talked amiably with them at the time and then turned their ire on anti-racist protesters. No rapid announcements warning the public were coming. If the APD was so concerned about gun violence, this would seem an obvious incident to highlight. But that didn’t happen. Only a brief, dry recitation of the later charges, which were finally issued after massive public pressure.

In other cases the disparities are particularly glaring.

On Aug. 31, 2020 a press release about a stabbing incident targeted a Black local and added a paragraph tying the incident to the supposed larger issues of violent crime. But when a white man was charged with assault with a deadly weapon the very same day, they didn’t.

On Nov. 23, 2020, a white man was charged in a stabbing and in the press release the APD didn’t attempt to tie it to a supposed crime wave. The next day when a Black man faced similar charges, they did.

With the start of 2021 the APD briefly tapered off mentioning crime numbers in specific incidents, probably because it was too early in the year for those numbers to sound sufficiently scary. But in April, as the annual city budget wrangling ramped up, they were back to it.

While the APD routinely called reports of gunshots in Black communities a shooting even when no one was injured, on May 11 when a white person was charged with opening fire on a Black person, the APD suddenly referred to it as “shots fired” instead. They did not tie it to a larger crime problem. Four days later, in a press release about gunshots in a Black neighborhood, they did, and claimed it was a “drive by shooting” to boot.

On June 20 of this year Henry Miller, the son of the former local GOP chair, opened fire on a pride party. Fortunately, no one was injured. But Miller’s arrest didn’t even rate an alert from the APD, let alone a caution about how this was another example of gun violence sweeping the city.

By blurring the stats the APD also intentionally left out key context. After all, by itself number of calls sounds like a lot without any context of how many the APD’s had in previous years. Interestingly, starting on March 10 2021 the APD briefly did compare numbers with last year’s in their press releases.

But about a month into this shift the crime numbers the APD were citing were actually lower than 2020’s. They quickly stopped and went back just to citing them with no context.

To be clear Asheville, like every city, has real issues of violence. But police don’t solve these and they create many more, like the APD kicking houseless people out of their camps on the coldest night of the year and regularly brandishing firearms at Black locals. Less than four percent of the APD’s calls deal with violent crime. The press releases were left to gin up fears about found shell casings and drug arrests. At the same time, the APD and city staff were refusing to consider emergency response alternatives and poverty relief that do actually reduce violence.

In cases where they do show up in the aftermath of a shooting the APD often botches things badly. In August of last year there was a tragic murder in the historically Black Burton Street neighborhood. The APD quickly put out a press release claiming this death was an example of the gun violence supposedly sweeping the town.

Blade reporter Veronica Coit, however, directly observed police making the situation worse: blocking medical access and ignoring obvious leads. Coit made a personal post about this countering the APD’s spin. Several days later cops dragged them out of their vehicle and arrested them while they were covering a protest. It took over a year to get the charges against them dismissed.

The spin doctors

While police departments aren’t the type to openly say “hey we’re shoveling cash to a shady right-wing pr firm to paint Black people as the problem” it’s indisputable that the city’s approach changed as Colepro came more fully on-board last summer, and documents show that behind the scenes Colepro was playing a major role in crafting racist talking points.. But except for a few articles the media firm has gotten fairly little coverage. Even when they’ve been featured in a critical light, their presence as portrayed as a reaction to the wave of public outrage.

An extensive set of documents obtained by the open government group Sunshine Request tells a different story. Colepro media and its sister firm, Critical Incident video, first start talking closely with city staff as far back Feburary 2020, when incoming chief David Zack pointedly recommended them. While they would play a role in damage control and the APD’s much-mocked attempts at feel-good social media content, the emails also show that they helped hatch a strategy to use the demonization of Black communities to shift attention from the APD’s own violence.

Zack had worked with Colepro in his previous job at the Cheektowaga, N.Y. police department. Over the coming two months APD higher-ups, spear-headed by Capt. Jackie Stepp, would hammer out a contract with Critical Incidents.

Colepro’s work is big business. The California-based company has provided pr services to 100 police departments in that state alone and in recent years has expanded its operations more widely throughout the country. An announcement for one their workshops show its title, “managing the mainstream media” and promises to teach cops how to “outsmart reporters.”

In the months before the uprisings, that record was also coming under increasing scrutiny. In April, for example, Sonoma County deputies attacked a Black man with a police dog and repeatedly tased him while he was on the ground. Colepro’s pr tried to excuse the cops, claiming the man was threatening them with a gun. But an extended video taken by a bystander revealed the full brutality of the attack, and that Colepro were just outright lying. No gun was ever found.

If they were even aware of it, neither city staff or the APD seemed to find any of this concerning.

That only continued throughout the year. As reported in the Monterey County Weekly, when a Pacific Grove, Ca. police officer posted statements like “Fuck Black Lives Matter” and lauded fascist murderers the department suddenly hired Colepro to stave off criticism. Their talking points encouraged officials to chide the public for their outrage, deflect questions and deny the presence of the far-right in law enforcement. They later threatened journalists for writing about this.

While Colepro (particularly its video division) was already on-board when demonstrations started in late May, their role would deepen as the uprisings continued. They personally put together Zack’s media appearances in the wake of the APD’s notorious attack on a medic tent, advised the city’s pr staff on social media posts (especially saccharine pr about cops’ supposed good deeds) and held multiple calls with the department’s pr staff.

At some points the firm’s right-wing perspective proved too much even for the APD. On June 24, Colepro staffer Sandy Soriano suggested a series of slogans for the APD, including “Believe in the Blue” (a riff on the far-right chant “Back the Blue”). Hallingse balked.

“Please don’t get mad at me or throw your computer, but I think we need to put some additional thought into these because I don’t feel like these resonate with Asheville residents,” she wrote.

Of course plenty of the APD’s interactions with Colepro aren’t captured in the documents: emails allude to in-person presentations, phone conversations and meetings. Several attachments to emails discussing pr strategy were pointedly left out of city hall’s document release.

But they show enough. As July wound on and many of the APD’s “feel good” style posts were falling flat, they decided to try another tactic. At the end of that month, right before the APD’s press releases seriously escalated, Colepro and city pr staff started to push to turn the discussion away from police violence and towards blaming Black individuals and neighborhoods.

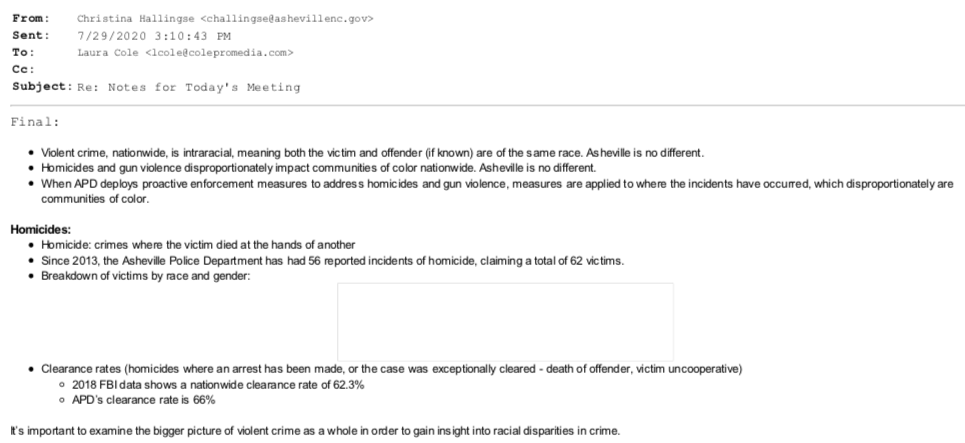

On July 29 Hallingse sent Linda Cole, the company’s head, a series of talking points for a meeting that day, based on topics they’d clearly already discussed outside of email.

Part of a July 29, 2020 exchange between Colepro media founder Linda Cole and APD pr flack Christina Hallingse, discussing racist talking points to excuse the APD’s “proactive enforcement measures” in Black communities

Specifically, she wrote that the APD was going to start emphasizing that “homicide and gun violence disproportionately impact communities of color nationwide. Asheville is no different” and a claim that “when the APD deploys proactive enforcement measures to address homicide and gun violence, measures are applied to where the incidents have occurred, which disproportionately are communities of color.”

To be clear, that last one is an open justification for the military-style occupation of Black neighborhoods the APD is known for.

“It looks good, we can talk more about it on the call,” Cole replied that day. Hallingse follows up by editing the talking points further, emphasizing that “it’s important to examine the bigger picture of violent crime as a whole in order to gain insight into racial disparities in crime.”

This is an old and ugly tactic, often summarized as the “Black on Black crime” myth. A favorite of white supremacists, it has been extensively debunked for years. Even according to federal crime statistics violence within Black communities has been declining steeply for decades, faster than among white populations. The most common form of gun violence is white men shooting themselves.

This was certainly not the APD’s first use of this tactic. In 2017 then-chief Tammy Hooper notoriously defended an officer brandishing a rifle at Black children walking through Montford by blaming gun violence in public housing. Earlier in the summer the APD had also used similar tactics, singling out Black people charged in the protests while trying to boost the false assertion that those being arrested were “outside agitators.”

But as Colepro’s involvement with the city deepened the APD would start doing this so far more blatantly and far more often.

On July 30, the day after sending Colepro staff her talking points, Hallingse reported to Cole that the apd’s pr staff had personally met with Zack to “discuss some PIO [Public Information Office] directions/needs for moving forward.” The same day Colepro’s staff also had an extended phone call with the police chief.

Cole hoped that the APD’s new direction, the combination of “feel-good” posts with portraying the police as the only thing stopping violence, will show that “the more we do this, the more the naysayers will see that this is the Asheville Police Department.” She and Hallingse would then schedule another phone call for late that night.

In the days after all that frenetic plotting the department’s social media resumed some of the earlier “feel good” style posts. But the APD’s barrage of press releases also escalated. In the first week of August 2020 the APD put out more than one a day, with every alert about a supposed crime targeting a Black individual or neighborhood. When the next anti-racism protest happened the APD cracked down even more viciously than before. The press releases were part of this repression, as the department made a point of revealing an unusually high level of info despite the charges (“failure to disperse”) being incredibly minor. Harassment and threats from the far-right naturally followed.

With Colepro’s influence the city began echoing far-right talking points even more closely, like claiming that a coffin left on the lawn in front of the police station as part of a memorial to Breonna Taylor and tombstones (listing Black people killed by the police) left on the lawns of city officials, were a violent threat. This was debunked at the time and since, but the it was brought hook, line and sinker in establishment media coverage sympathetic to the APD.

When far-right stalker Chad Nesbitt fell and struck his head on a parking meter, the APD’s pr claimed he was a victim even though video revealed that he stumbled after his cronies tried unsuccessfully to shove their way through a crowd of protesters.

Part of Colepro Media’s August 2020 contract with city government. Their role in crafting news releases and advising the department’s pr is specifically noted

Meanwhile Colepro was finding all this quite lucrative. In the same week that the APD’s strategy they finalized a contract with city hall, promising them up to $60,000 a year for their work.

‘Still shoot them the next day’

In practice, the APD’s racist pr offensive served as one prong of the city’s strategy to preserve the status quo, but one that’s not gotten the attention it deserved. On the one hand there’s been a steady push back from the idea of actual reparations. City officials are now maintaining that more hotels, more tourism and the same programs they’ve been doing for years constitute “reparations” but direct cash payments and the return of land stolen from Black communities don’t. Even those thin “reparations” have now been pushed back years.

When Black abolitionists have spoken up they’ve been silenced or threatened. When white accomplices and allies have responded to their calls for action their presence is used to falsely portray abolition as just a belief of some white leftists.

While city hall’s supposed racial justice agenda is watered down to mild reforms, then to nothing, there’s been a concerted effort to retrench the police. Official city reports have commended officers for using tear gas against protests and even sought to excuse the destruction of the medic tent. Mayor Esther Manheimer threatened locals speaking in favor of defunding with arrest during the annual budget hearing. The narrative set by the pr barrage is part of that.

Indeed if Colepro’s goal was to “manage the mainstream media” overall the press in Asheville enthusiastically fell for it. Police talking points were prominently featured by outlets like WLOS and the Asheville Citizen-Times, as were no shortage of crime stories based on the APD’s press release barrage. Prominent columnists took the police chief at face value and dismissed the growing movements for defunding and abolition.

Through this all Grits, who was on the front line of many of these struggles, observed that despite “crying wolf” over their supposed lack of resources the APD kept on harassing Black communities.

“I live in a Black neighborhood, my grandmother lives in a Black neighborhood, she doesn’t even know that half of the police force quit” they tell the Blade. “You see them every single goddamn day in our Black neighborhoods.”

“Why the fuck are they just sitting, eating doughnuts in the fucking road along PVA? Why are they sitting at the edge of Hillcrest all fucking day, menacing people? It’s ridiculous,” they add. “This is housing intentionally constructed to look and function like prisons, then you put all the Black people in there. You’re not repairing anything and waiting until people throw their hands up.”

During council’s June 22 budget vote Council member Antanette Mosley — who was controversially appointed by city council instead of the seat going up for election — used the sort of talking points honed by Colepro to claim that a reduced police force actually hurts Black people, especially Black women. At the Aug. 24 meeting she falsely claimed that some white speakers calling for defunding showed that it was exclusively a white-driven effort. She claimed she had talked to some Hillcrest residents who wanted more police.

Mosley was using an old tactic that white liberals — often ignorant of politics within Black communities — frequently fall for. Black communities are not a monolith. Officials and groups within them that support the status quo tend to get disproportionate attention from white-dominated media, while movements for actual change get minimized even when they have widespread support. Mosley, a well-off lawyer with conservative politics, is essentially pushing the same position as the police chief.

There is, nationwide, a push to bring more attention to the prevalence of police violence against Black women.

In Asheville Black locals have since the start been at the forefront of the push for defunding, from the earlier “Million Dollars for the People” effort to last year’s uprisings to taking over council’s public comment to a literal mural reading “Defund the police.” The call to cut Asheville police funding by half emerged from the multi-generational Black Avl Demands collective.

Indeed, council’s last in-person meeting, on July 27, saw plenty of Black locals show up to criticize stricter noise ordinance rules (which disproportionately targets communities of color) and city hall spending millions on a new police station. The mayor cut their time by a third compared to earlier (mostly white) speakers.

Grits called in from quarantine to speak. As they demanded “divestment from the police” the mayor cut them off and quickly adjourned.

To them, city hall’s combination of pretending to care while oppressing Black communities isn’t particularly new.

“The city of Asheville has promised so many things to the Black community they haven’t kept,” they said. “They passed this resolution saying they want to address these harms, they make these grandiose statements and then it’s all just hearsay.”

“To make such a grandiose promise and then do virtually nothing causes such significant harm,” they add. “They take some ice cream to the hood and they still shoot them the next day.”

They’re also unsurprised by ColePro’s actions, noting the group’s long record of lying about police violence against Black people.

“They pop up in all these fucking cases, defending the cops.” Grits said, until their pr runs afoul of reality. “Then there’s a video that contradicts law enforcement’s statement. The fact is you lied.”

But when violence from white people happens “they cover it up, without missing a beat.”

Grits sees a city hall “averse to any suggestion from the community.” While they believe locals should keep fighting local government and “should be giving them hell” they should also look to take on oppressions on the ground with mutual aid efforts and organizing that’s hard for governments and the non-profit complex to shut down.

“We need to support each other and what we can do in communities,” they continue. “Right now mutual aid is the closest we can get not even to repair, but to where we can imagine what reparations look like.”

Colepro’s propaganda, they remind, is just the latest part of a very old evil.

“I grew up in this city, the cops have always been over-policing our Black neighborhoods, killing Black and Brown people, covering shit up.” Grits said. “These numbers aren’t startling at all.”

—

Blade editor David Forbes has been a journalist in Asheville for over 15 years. She writes about history, life and, of course, fighting city hall. They live in downtown, where they drink too much tea and scheme for anarchy.

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by our readers. If you like what we do, donate directly to us on Patreon or make a one-time gift to support our work. Questions? Comments? Email us.