Touted as an innovative transformation, Project Aspire is instead something all too familiar: gentrification pushed forward to the detriment of a local Black community. Inside the mega hotel project and its modern-day redlining

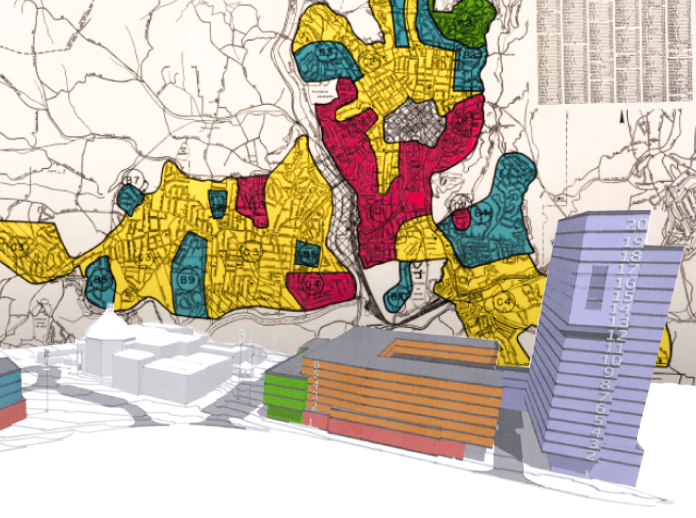

Above: Plans for Project Aspire overlaid with the 1930s redlining maps. Graphic by Orion Solstice

Editor’s note: This article is one of the first to use a change in the Blade’s style. Instead of referring to a project with a portion of “affordable” housing as, for example “20 percent affordable units,” as city government and most media do, we will now refer to it as “80 percent unaffordable,” to more accurately convey how deeply out of reach most of the housing built in this town is for most of the people who live here.

We will continue our long-standing practice of using “affordable” in quote marks to refer to units that are officially designated so by governments but are not, in practice, affordable for many working locals. — D.F.

[This article quotes and links to historic government documents related to the redlining of Black communities, some of which use openly racist terms]

In town where the powers that be treat jargon-laden gibberish as a fine art form, the babble used to prop up Project Aspire, a massive joint venture between the YMCA and First Baptist, still stands out.

“I invite you and all the city of Asheville to catch a glimpse of this dream that could transform our city for the better” First Baptist chief pastor Mac Dennis declared to city council Sept. 12. “Let love make of each one of us an inventor, and we will do something that will make the ears of all who hear it tingle.”

“Two words that came up a lot were audacious and transformation,” regional YMCA head Paul Vest declared.

“Project Aspire is not just a development, it is a testament to the power of mission-led partnership, community engagement and shared vision,” Robert Papilton of Furman Company developers declared. “This legacy will benefit Asheville for generations.”

“Transformative for this part of downtown,” city hall principal planner William Palmquist said.

“Project Aspire provides a new start with the Black community that was cut off by urban renewal,” wrote Robby Russel, a banker and former YMCA board member who now lives in Chapel Hill, wrote in a Sept. 17 Citizen-Times column.

“Catalyzing new and significant affordable housing,” claimed Clark Duncan, a senior vice president with the chamber of commerce (and YMCA board member). “It will build a place where we all feel at home.”

“A transformational East End gateway to downtown,” former TDA Bank President Charles Frederick, who will chair the YMCA’s financing push for the project, said.

Any time the hacks raid their word hoards this hard, it’s worth taking a closer look at what they’re trying to hide and who it’s going to hurt. The devil, as the communities facing the brunt of this project have repeatedly pointed out, is in the details.

Since its late September passage the mega-development has, for the moment, fallen out of the headlines. Most of the establishment media coverage at the time largely bought into the hype while quoting a few opponents for good measure. That underrates how big a deal this is, not in how much good could it could do but in how it will push the absolute worst kind of gentrification.

To hear its boosters tell it Project Aspire is the salvation to Asheville’s housing problem, filled with amenities for the benefit of all, “serving the community for generations to come” as Vest put it. Dennis even compared it to saving refugees in Burundi (no, I am not making this up).

It’s not. While its supporters have touted the renovated YMCA building and the services it will offer, including a promised clinic, the 10-acre development is primarily dedicated to cold profit. It’s based around a giant luxury hotel that promises to be one of the tallest buildings in Asheville. An overwhelming 80 percent of its hundreds of housing units will be unaffordable even by the city’s own standards, catering to the well-off and transplants looking for second, third or fourth vacation spots. Or airbnb types looking for some extra units to hock knowing that, while technically illegal, city hall will likely let them get away with it.

The remaining 20 percent will be “affordable” in name only, as it will still take well over $40,000 a year — an amount many downtown workers can only dream of — to live there without it seriously straining one’s budget.

In an exercise of that famed churchly charity Aspire is setting half of those — just 1 in 10 of its total units — aside for locals with Section 8 vouchers. This is framed by developers and city officials alike as an act of amazing self-sacrifice. It is the opposite. Refusing housing vouchers throughout 90 percent of a project is literally declaring “we’re turning down guaranteed money because we hate poor people.”

Any time a demand for more — like the usual minimal contribution to the city’s affordable housing fund expected of a new hotel — is made, the developers threaten to cut even the paltry amount of slightly-less unaffordable housing they’re offering.

Instead Project Aspire’s set to demand public funds *pay them* incentives to build a development that is overwhelmingly expensive apartments and a giant hotel.

It gets yet worse. Most damagingly Project Aspire threatens to further gentrify the historically Black East End/Valley Street neighborhood, already hit hard by redlining, with the massive hotel even cutting off its light.

While the ministers and developers behind the project have poured out acknowledgements of the evils of racism, these haven’t included meeting any of the community’s incredibly modest demands, like not living in darkness so rich tourists can have a nicer view.

Indeed, they balked when residents proposed giving them any actual share of Aspire’s profits. Both the project’s boosters and city officials are salivating at the prospect of increased property tax revenue, but that also means values will shoot up in the area. In Asheville that means Black homeowners and renters will disproportionately bear that cost.

At the Sept. 26 Asheville city council meeting, where Project Aspire got its initial approvals, the East End and other locals opposed to gentrification — no matter how many Bible verses were deployed to justify it — showed up in force.

As they have for decades, particularly since 2020, the vast majority of council responded to Black communities’ clear demands by doing the exact opposite. It is a notable trend in recent years that the more racial justice proclamations that pour forth from city hall, the more Black locals are driven from their homes.

For all its pretenses Project Aspire is not something new, but something very old: cashing in on tourism and catering to the wealthy at the expense of Black communities.

Redlining never left.

The spire

The charm offensive on behalf of this development has been pressed relentlessly, obscuring in the process much of what it actually is.

Project Aspire will, assuming it all gets built the way its planned, include a renovated YMCA, a much-touted clinic and non-profit spaces, 400 to 460 residential units, 165-300 hotel rooms in that giant, 20-story spire and up to 1,800 parking spaces (mostly in parking decks). The vast majority of the units in Aspire will be unaffordable (“market-rate”) apartments and luxury hotel rooms in one of the least affordable cities in the country, both offered at rates geared towards making as much profit as possible. The Aspire in the project’s name seems to mean “aspire to make a ton of money.”

It’s worth pausing for a second to remember that those behind are supposedly non-profit organizations. Neither of them is exactly hurting for cash. First Baptist is one of the most established churches in the city, its parishioners leaning heavily WASPy and wealthy.

The YMCA is firmly entrenched in the non-profit complex. Its 2020 tax filings, the most recent available on its website, declared $47 million in assets. Vest himself raked in over $250,000 in salary and other compensation.

Because Project Aspire’s p.r. effort is also painting opposition as just some random dislike of large buildings, change and “progress,” it’s worth being clear that density is not, in and of itself, bad. Indeed dense communities, actual communities, are desperately needed in cities.

But it depends on what’s being built and for whose benefit. In Aspire’s case it’s overwhelmingly housing, shops and hotel rooms for the well-off and white. Again and again critics have generally not been gentry NIMBYS but locals opposed to yet another giant hotel and the effect it will have on the nearby neighborhood, especially forcing out Black locals.

The YMCA and First Baptist say the project’s been in the works for years, supposedly with each step the result of extensive community outreach. Indeed YMCA representatives hoped that the project itself would “build bridges” with the local Black community.

But this, according to the residents themselves, is untrue. East End residents have repeatedly declared that their concerns were not listened to and they were not informed about the hotel — the part they most opposed — until the project was barreling forward to council approval.

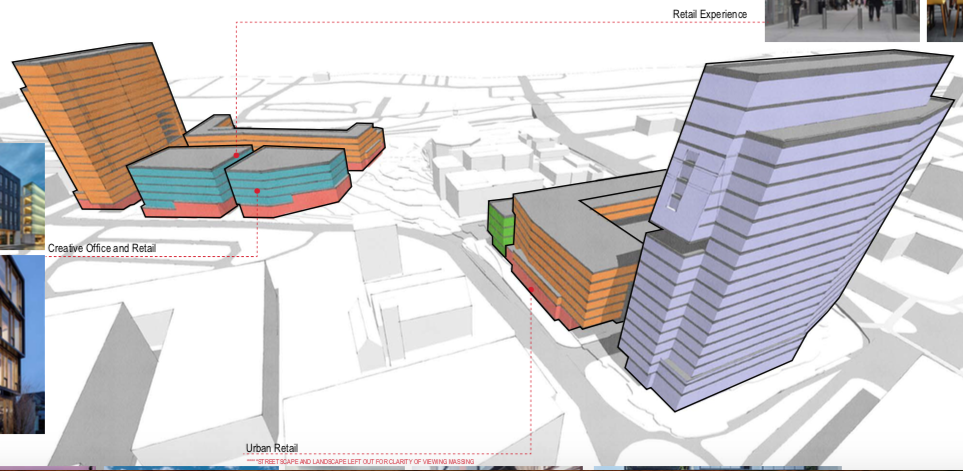

Indeed, as someone who’s covered city government here for nearly 20 years, the way Aspire was presented to the public was downright deceptive. The drawings chosen by the developers and city staff were direct overhead views or other plans. They left out other projections that more clearly show the project for what it is: luxury skyscrapers looming over a Black community. Those were instead in the developer’s full 68-page proposal to city hall, tucked back in an appendix to the public documents released for the hearing.

One of the images more accurately showing the scale of Project Aspire’s mega-hotel. These were incidentally left out of city hall and the developer’s presentations to the public

There was more. As a massive hotel, Aspire would normally be required to give a set amount of cash to city funds for housing or social services. This was the “social benefits” that council had mandated when they opened the floodgates on hotels back in 2021. While always a thin facade, in theory these were supposed to offset at a tiny bit of the hotels’ impact on locals.

But when asked, Sept. 12, if they were going to pay the $1.6 million they’d owe under that set-up, Aspire’s developers dropped the sanctimonious facade and declared they weren’t going to give a cent.

“We could write a check for the community benefits, at $6,000 a unit and put it into your housing [fund] and we wouldn’t build any housing,” Papilton said, adding that officials even asking them to put the usual contribution “honestly feels a little bit unfair.” God forbid.

As even council member Sage Turner noted at that meeting, Aspire had “skipped the typical process,” though this wouldn’t stop her from later voting for it.

At that meeting the doubt on council was enough that the developers decided to delay the initial approval vote until the next meeting on Sept. 26. Importantly delaying projects like this also makes it harder to rally community opposition to them. It’s more difficult for working class locals to frequently spend hours sitting in government meetings.

‘A second urban removal’

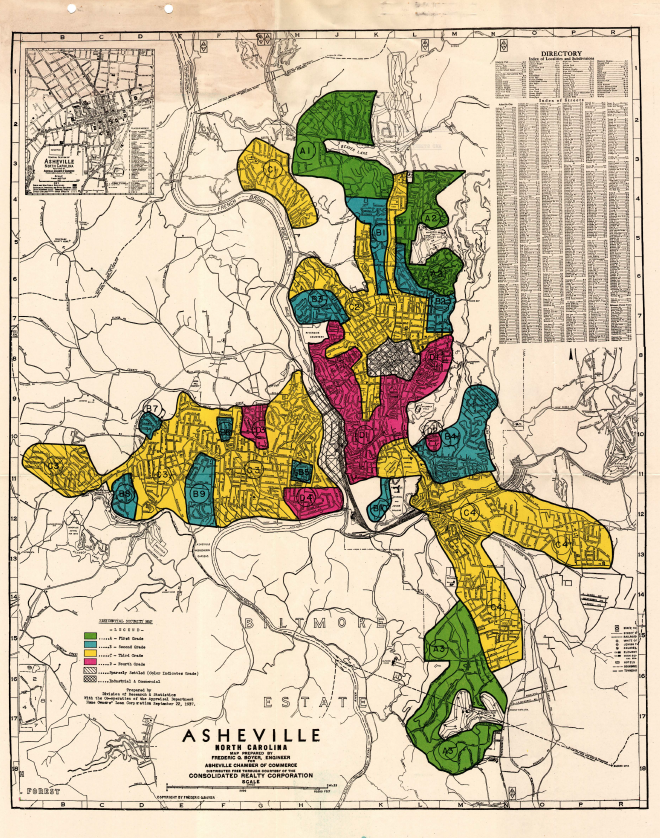

The 1937 HOLC map of Asheville. All but one of the areas marked in red are majority African-American. East End/Valley Street are the red areas to the east of the core of downtown. Image via Mapping Inequality

One of the many reasons history’s key to journalism is because it’s important to know the ground you stand on. That history, despite attempts to sideline and erase it, loomed large over the Project Aspire vote.

The East End neighborhood was devastated by local governments, in cooperation with federal and state authorities, over the course of several decades as “urban renewal” demolished homes and businesses, severing entire communities. They did so based on federal maps that used the segregationist practice of redlining, designating Black and multiracial neighborhoods as “blighted” and ripe for destruction based on little more than outright bigotry.

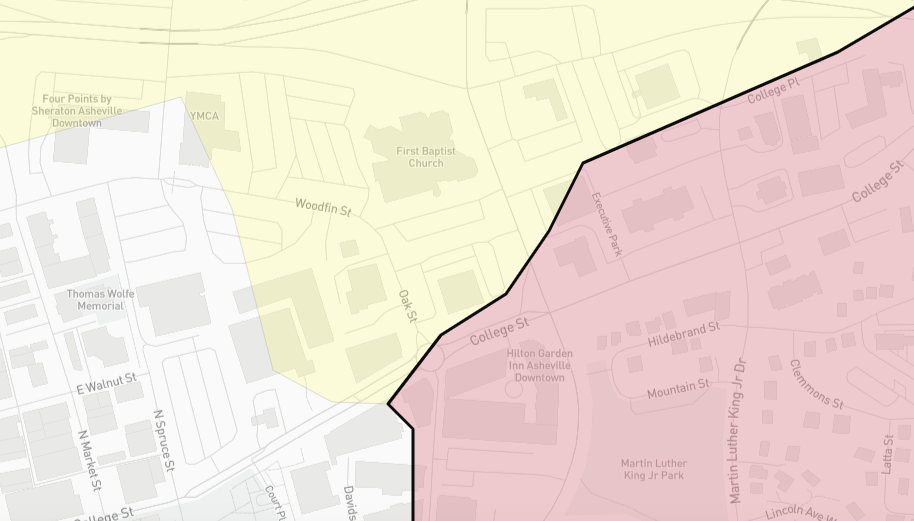

The Oak Street properties planned to hold Project Aspire sit right on a key boundary in the redlining maps produced in the 1930s, between a tract in yellow (“distressed”) and the East End/Valley Street neighborhood marked in the maps’ notorious red.

Image of the redlining maps super-imposed on the area of Asheville designated for Project Aspire. From Mapping Inequality

What made the “distressed” neighborhood north of the East End so? One of the major factors the mapmakers noted was “infiltration of Negro slowly in area.” In the coming decades policies were intended to crush that “infiltration” and destroy Black neighborhoods like East End.

While this happened in every city in America, in Asheville the destruction was particularly catastrophic, especially in the East End and Valley Street neighborhoods. By some measures half of the city’s Black population lost their housing during the two decades of urban renewal, possibly the worst in the entire Southeast. Hundreds of homes and businesses throughout East End/Valley Street, Southside and Burton Street were destroyed.

Black locals have rightly dubbed it “urban removal” or, even more bluntly, “negro removal.”

That too was dubbed progress, and was touted in terms of the increased cash the “renewed” areas would bring in to local government coffers through hiking property values.

Given that history it must be said that while there were a smattering of locals who genuinely believed it would help with the housing crisis, there was a clear contrast between those who spoke in favor of Project Aspire and who opposed it. They were bankers, executive directors, retirees, transplants and property owners. They were mostly white and well-off, and the exceptions were generally those whose organizations stand to directly benefit from the project.

From experience covering local government, when this many financiers cheer a project it never turns out well for most of the people in its path.

Aspire’s opponents, by contrast, were mostly Black and overwhelmingly working class. They instead reflected the kind of multi-racial coalitions that sprung up during 2020 and which city hall, the cops and the non-profit complex have since worked frenetically to crush.

In his Sept. 17 Citizen-Times column Robby Russell, the banker and former YMCA board member, wrote from Chapel Hill that “Project Aspire extends a heartfelt welcome to the East End and Valley Street communities.”

The communities weren’t buying it.

“As I sat and watched the sea of caucasity that preceded me, only two people even mentioned the community that’s going to be impacted by this, and that’s two Black people, both speaking on behalf of the YMCA,” Kimberly Collins, representing a group of East End residents, said at the Sept. 26 meeting. “This whole project sits within historic East End/Valley Street. So much that land was taken so that some of this property could be built upon.”

“It’s funny, the YMCA has been present in Western North Carolina for over 130 years, and it’s only now, through the Aspire project, that they’re going to be making this outreach to the Black community?” Collins continued. “When it comes to people wanting to see progress they only want to see progress through their lens, they don’t want to see progress through the lens of the people it truly impacts: the Black community.”

Indeed, the YMCA has been located in its current spot, just down the street from East End, for 53 years years. According to the organization itself that’s been so long that the facility is now falling apart and needs to be replaced by the shiny new center they’ll get as part of Aspire.

Collins accused the developers of a “bait and switch,” noting during their meetings with East End residents about plans for the project, “they never came back to us and said anything about this hotel before it came to council.”

“What about the Black people being pushed out by projects like this?” she concluded. “Let’s be clear, Aspire will raise taxes on the East End community, which is another form of redlining and eminent domain. You’re going to take it through taxation because the elderly will not be able to pay their taxes. You are driving them out. Aspire will do this. That 20 story building will do this.”

The community’s demand, Collins declared, was simple: “go back to the drawing board.”

“I personally watched a Black community turn into a multimillion dollar project that pushed out just about every Black homeowner on my block,” Nina Ireland told council. “I see that there’s a second urban removal wave.”

Ireland noted that in a recent meeting between East End residents and Project Aspire representatives, “we were personally apologized to by the pastor of First Baptist about the Black community that was pushed out for their church to be built.”

“But why say sorry when you have the power and privilege to go beyond sorry? It doesn’t pay nothing, it doesn’t change anything.”

Ireland noted that the pastor’s mood suddenly changed when she asked about the East End directly profiting from the project.

“The community is going to be impacted, so why can’t the community have part ownership to help offset the rising property taxes that will inevitably happen. Why can’t something come out of a physical apology instead of a verbal apology? We know Asheville loves some hotels, we know y’all love to put hotels up, city council.”

“We will still have affordable housing problems after this hotel. Last I checked the rich doesn’t want to live with the poor.” Ireland concluded. “So all this stuff y’all are dressing it up with are just buzzwords.”

Mayor Esther Manheimer then tried to cut Ireland off (she’s got a long record of doing that to Black speakers at council meetings), but she instead turned to face the crowd and talked to them directly, thanking those who opposed the project.

Other speakers pointed out Aspire’s tie to the wave of gentrification hitting the city.

“We keep losing space, we keep losing real estate, we keep seeing rents go up,” Lisa Alpert said. “People talk about ‘oh, progress’ but I’m not seeing progress. Progress would be a rent cap. Progress would be a minimum livable wage for all businesses in the city.”

“I look around Asheville and I see the Flat Iron where we lost so many small businesses, I look around to the Tribute, an absolute blight on our cityscape, I look at the Radical being built in the river Arts District, which was built by artists, train hoppers, weirdos. We’re losing our space. I know so many musicians and artists who can’t afford studio space, they can’t afford rent. [The hotel space] could have gone to that.”

“I’ve witnessed the Black community, our presence, our history, our voices, be erased, removed, diminished and excluded from any progress in this city,” Paul Howell said, his words a sharp contrast to the bank president who preceded him. “All this ‘affordable housing’ talk is fine and dandy but when it comes down to it there’s nothing affordable about the housing they’re offering.”

“I feel for the people that are in housing conditions right now pushing for this project, because the project has nothing to do with their immediate concerns and conditions.”

But city council acted as one would expect, with the majority of its members lining up behind the bankers, developers and non-profit heads whose interests they serve. Vice mayor Sandra Kilgore, a conservative realtor and the sole local elected official to vote against removing the segregationist Vance monument, even chided Black residents for opposing Aspire.

Council member Sheneika Smith asked the developers if they could reduce the hotel by five stories. When they outright refused she still supported it anyway.

Only two council members actually bothered listening to the public.

“I don’t think surrounding our historic neighborhoods of East End/Valley Street and Southside [with hotels] is appropriate; we’re not doing that with any other neighborhood,” Council member Kim Roney said. “Now we’re going to have to plan on subsidizing parking and plan on subsidizing the affordable housing. We all know, due to Buncombe county’s tax structure, that Black neighborhoods historically pay the most property taxes. I’m not ok with that.”

“I have literally never seen an incidence where a majority community has ceded ground to a minority community, even when the minority community purports to speak for itself. It seems as if tonight will be no different,” Council member Antanette Mosley declared. “I am listening to the people most affected when they say what they need. I don’t think we’re in a place where saying ‘I hear you’ is enough. We’re in a position to do something about it.”

“We constantly discuss how aware we are of the history, how much the history pains us, when we talk about placing 600 places to live in that area I go back to the fact that there were 600 homes already there that had been removed by urban renewal.”

This shouldn’t be construed as an endorsement of either official — we’ve criticized Roney and Mosley plenty and we’ll do so again — but it was a telling how them stating obvious truths were a sharp contrast to the ream of babble from the rest of council.

I’m sure the other five members deplore redlining, of course, but somehow that never seems to extend to doing anything to stop it.

Redlining redux

A 1964 booklet from the Housing Authority of the City of Asheville, touting increased tax values from ‘urban renewal.’ From UNCA, D. H. Ramsey Library Special Collections

“What you see in Asheville is stunning: the urban renewal projects coincide precisely with the redlined areas in the 1930s. There’s absolutely no room for speculation here: it’s one policy seeping into another. Those neighborhoods that were singled out under redlining — and labeled as areas that should not be reinvested in — come out of the 60s and 70s policies selected as candidates for…eminent domain”

“…This showed the persistence of these policies, even when they’re outlawed or rendered unenforceable. Once these tools are in place it almost becomes self-fulfilling. You don’t even need to enforce them.”

— Richard Marciano, University of Maryland, expert on redlining

“We see you, we hear you, your concerns are valid. The tear gas begins in one minute.”

— joke from the 2020 anti-racist protests, summing up the contrast between city hall’s words and actions

It’s worth remembering that urban renewal too was touted as a “transformational” change that would bring nothing but public good, while those who opposed it were dismissed as simply standing in the way of progress, rather than clearly seeing a danger to their communities and bravely fighting back.

Similarly important to recall is that a handful of relatively well-off figures within marginalized communities spoke in support of urban renewal, giving it essential cover. Some did so from a genuine, but tragically mistaken belief, that it would improve things. Others were simply bribed or sought to get favor from the elite.

Reading through the old brochures put out by the proponents of “urban renewal” it’s stunning how much they resemble Aspire, especially in the rhetoric of inevitable progress.

Indeed, at the Sept. 26 meeting Skyler Duncan a recent transplant and supporter of Aspire claimed “fear usually comes from the unknown” and chided opponents that “fear is the lack of understanding of opportunity.”

Ultra-gentry council member Sage Turner warned Black neighborhoods and others opposing Aspire that “you can’t stand in the way of progress.”

Whose progress? Whose opportunity? Duncan is a financial advisor at Merrill Lynch. Turner lives in a mansion in a gentrifying neighborhood and built her career on worker exploitation.

Meanwhile, for most of the people who live in Asheville, and especially for the city’s Black communities, these vaunted pushes for “progress” have overwhelmingly been a disaster.

Asheville’s tourism “boom” has seen Black household wealth collapse, food insecurity rise and this city become one of the least affordable in the entire country. Rents here have skyrocketed 37 percent just since 2020. The police department treats activism, journalism or just being poor as illegal. City hall has consistently changed or outright ignored its own rules to please hoteliers and airbnb landlords, kicking hundreds out of their homes.

Locals aren’t vaguely against change; we’re fighting for our lives against very real evils.

Because city hall pushes gentrification over all, “urban renewal” has entered the long list of racist atrocities which it loudly, publicly mourns while doing everything possible to repeat.

Yet things are not hopeless. It is a common lie of Asheville’s establishment that they cannot be questioned, challenged or defeated. They wish us to believe that their verdicts are final and, most importantly, that we are powerless to change them. When communities stay determined to fight they have a lot harder time carrying out business as usual.

So it’s worth remembering that Project Aspire will have to come back to city hall. First it will need to siphon off public funds to subsidize its hotel rooms and luxury apartments. Then there will be years of additional hearings every time they have to push through something else or make some inevitable change.

Each one of these is a weak point, a chance for the East End and everyone else opposed to racist gentrification to rally opposition, disrupt the sham “process” and inflict as much misery upon those determined to re-enact redlining as possible.

Such projects are more fragile than they seem; with enough setbacks and delays they will get scrapped.

And make no mistake, the type of gentrification embodied by Aspire is a threat to us all.

Unless you’re white, cishet and wealthy — the vast majority of us ain’t — the city the gentry and their servants in local government want is not for you. They may stagger the times and nature of the attacks, but rest assured they’re coming for every last one of us sooner or later.

Needed now, more than ever, is strong multiracial resistance to gentrification, united by the task of saving our communities and by the blunt fact that the same rich assholes want us all gone.

—

Blade editor David Forbes has been a journalist in Asheville for over 15 years. She writes about history, life and, of course, fighting city hall. They live in downtown, where they drink too much tea and scheme for anarchy.

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by our readers. If you like what we do, donate directly to us on Patreon or make a one-time gift to support our work. Questions? Comments? Email us.