Fully-treated water returns amid serious concerns about lead and a dangerous push “back to normal” from city hall. Asheville’s long-neglected water system was smashed by Helene and the resulting crises are still unfolding. What’s going on, what we know and what you can do about it

Above: Water flowing into a sink at this reporter’s home, part of regularly flushing out the lines due to concerns about potential lead contamination, particularly in older housing, due to the impacts of the water crisis. Tens of thousands of locals are currently doing the same

On Nov. 18 came the announcement locals had awaited for nearly two months:

“The City of Asheville has lifted the boil water notice for all water customers as of 11 a.m. today, November 18.

Water resources lab staff finished sampling the distribution system early Sunday afternoon, and the results have confirmed that the water supply is free of contaminants.”

In short, they proclaimed “customers may resume normal usage of the water system. It is no longer necessary to use bottled water for consumption.”

But a mere two paragraphs later the announcement struck a very different chord.

“Plumbing in structures built before 1988 have increased potential to be a source for lead exposure if water sits undisturbed in plumbing. For this reason, customers in structures built before 1988 are advised to flush their system for 30 seconds to two minutes before consumption on a daily basis.”

A government declaration that veers from “free of contaminants” to “oh, by the way, much of the city may have to worry a dangerous neurotoxin” is, to put it mildly, not exactly a recipe for calm. Indeed, rather than a celebratory return to functioning infrastructure after a long ordeal, many locals understandably expressed skepticism, confusion and anger at the dangers they still faced.

Just few days before, on Nov. 14, city officials had also announced that water testing found lead in the pipes of seven schools scattered throughout the area.

In the weeks since over 6,000 locals have received test kits, but we won’t know the results until later this month. City government has also released a map that provides more information on if your housing has lead in its plumbing, though in many areas it’s uncertain.

On Nov. 18 Mayor Esther Manheimer, whose policies have played a major role in the water system’s deterioration over the past decade, followed up the city’s announcement with her own. She celebrated the return to “normal” by foisting responsibility for dealing with lead onto the public, asserting falsely that the advice for flushing lines for lead was “like it was before Helene.”

This went over like, well, a lead balloon, and not just with wary members of the public. The day after the boil notice was lifted the Mountain Xpress published a detailed open letter from Sally Wasileski, chair of the UNC Asheville Chemistry Department, warning about the potential dangers of lead in city water.

She noted this was due to the 19 days in October when the system pumped water directly from the North Fork reservoir, with heavy chlorination, through the lines. The results from the schools raised the possibility that this could have damaged the protective coating created by the system’s usual anti-corrosion treatments.

“Addressing this problem with consistent and transparent messaging is critically important, especially as the boil water notice has been lifted and residents across Asheville may begin to consume water from their homes,” Wasileski wrote. “Widespread compliance of the new addition to the alert to flush for 30 seconds to 2 minutes on a daily basis is insufficient without proper public education.”

“We can not risk widespread lead poisoning, especially on top of all that our community has faced in the wake of Helene,” she concluded. “We need a broad investigation of the lead levels at the tap of residences, schools and businesses who source their water from Asheville City Water.”

She also called for “immediate blood testing” of anyone who drank city water after boiling once some service resumed in October. Notably the Blade recommended at the time that locals only use this water for flushing due to exactly this kind of possibility.

So, what’s going on?

If you’re looking for a direct recommendation about what to do with the water, we second the advice of Wasileski and other independent experts: continue to use bottled water for cooking and drinking until you get lead test results back. Take a blood test if you’ve been drinking tap water, even after boiling. If you’re in an older home flush your lines each morning or if you’ve been away for over four hours.

To add insult to injury, city and county governments used the Nov. 18 announcement as an excuse to swiftly shut down the vast majority of their community care and water distribution sites. Here’s a regularly updated list of groups still offering supplies, including bottled water.

Those in housing built after 1988 or that verifiably don’t have lead pipes are at significantly less risk, but for most of those on city water it’s still worth being wary. The housing supply here is old, and most people live in buildings constructed when the use of lead was far more common.

In this piece we’ll delve into what happened to Asheville’s water system when Helene hit, the emergency measures done alongside its extensive repairs and some of the ensuing aftershocks. We’ll clarify what we can and be transparent about things that just aren’t, as of this writing, known.

The fact is that Helene collided with an aging water system already prone to some serious issues. Our society tends to think of natural disasters as singular events. But as anyone who’s lived through one knows, their impacts last for a very long time afterwards. In many ways this disaster is still unfolding, furthered by decades of inequality, neglected infrastructure and a premature rush “back to normal” in hopes of reviving tourism. Our water is no exception.

The hammer blow

Asheville’s water system was, long before Helene started to form in the Caribbean on that horrific week in September, not in good shape. Multiple administrations at Asheville city hall, including both conservative and progressive councils, had kept up a corrupt policy of cutting big business a massive discount on water rates. At times this led local residents — over 150,000 people get water from the system — to pay rates nearly forty percent higher than the national average while corporations paid far less than elsewhere. Indeed the water system actually charged companies less, a lot less, the more they pumped.

It also meant that an already-aging system languished without widespread, desperately-needed upgrades and line replacements. For over two decades households on Asheville water have often paid very high rates for a very bad system known for draconian bill enforcement and leaving them in the dark during crises. State laws that limited the water system’s revenue-raising powers didn’t help, nor did a prolonged — and unsuccessful — attempt in the 2010s by the far-right general assembly to seize it and set it up for privatization.

But while those were real issues, local officials also used them as an excuse for their own role in badly neglecting the many problems under their control.

Fortunately, one key exception was the massive North Fork Reservoir near Black Mountain, which provides the vast majority of the system’s water. In 2019 the height of the dam was raised and increased safety measures were installed. During the worst of Helene these kept the dam from collapsing entirely and saved thousands of lives.

But much of the rest of system wasn’t so lucky, and its aging lines remained a serious vulnerability.

In 2019 a major break in those led to downtown and West Asheville being under a boil advisory for over 48 hours. Over the following year the system racked up the equivalent of one boil water advisory a day somewhere along its labyrinthine length. In the last days of 2022 and the first weeks of 2023 freezing temperatures and serious failures in preparation resulted in a major crisis, with over half the system cut off from water for nearly two weeks. In both these disasters public alerts, when they came at all, were often contradictory or vague. City hall’s poor communications and lack of transparency on this front became notorious, as murky as the water that spurted from locals’ faucets.

One telling fact about the state of Asheville’s system was that the water stockpiles I bought in the wake of the 2023 crisis were what I drew from to help survive the first days after Helene.

Despite the 2023 crisis and the widespread public outrage that followed, that year city council did the chamber of commerce’s bidding and once again hiked rates substantially on residents while keeping the massive discounts for big business. Only this past summer, with an election on the way, did they finally start to change course and raise business rates, though still not nearly enough.

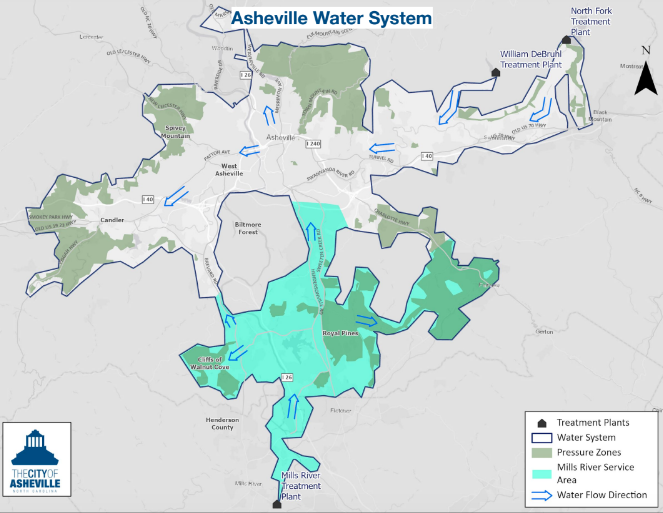

A map of the Asheville water system from a Jan. 10, 2023 city council presentation following the major winter failures at the beginning of that year. After Helene, only the Mills River plant remained functional, and only some of those in its service area had water.

Like with so many of their decisions the highest echelons of city hall seem to have bought into all that tourism marketing when it came to preparing for another crisis. Asheville was, the line went, a “climate haven” immune from real disasters or breakdowns; certainly there was no need for them to actually take serious action. Even two major system outages in four years wasn’t enough to shake this illusion.

Not coincidentally, the city manager and the vast majority of council are drawn from the ranks of the gentry, who enjoy a far cushier life than most of the people in this city. That tends to cultivate a certain refusal to face reality.

But hurricanes do not care about marketing, any more than viruses do. So when Helene hit the Asheville water system it was as a sledge hammer to an already-crumbling foundation. While a storm of its size and power would have posed a serious challenge even with decades of better water policy, the systemic neglect made things far worse than they had to be.

While North Fork’s upgrades prevented an even more apocalyptic catastrophe, all the water mains connecting it to the system were crushed and the winds that raged through the normally calm waters flipped its sediment to the top, turning a clear lake into a muddy pool.

As North Fork is, by far, the heaviest hitter among Asheville’s three water plants (only the much smaller Mills River facility, serving South Asheville, remained operational) the result was that the vast majority of the system lost water entirely. The rest, the part served by the Mills River plant, was under a boil advisory.

At first the main focus was on building a new water line to connect the reservoir to the rest of system. And building, not repair, is the key term here. The previous water mains connecting the North Fork, its main lines and back-up alike, were all washed down the river. A new line had to be built almost from scratch.

This was the sort of task that would typically take over a year. Through a lot of outside help and a stunning amount of work by crews on the ground, it was done by the early morning hours of Oct. 10.

A city of Asheville photo of water crews after connecting a major line to the North Fork reservoir on Oct. 10

The next major problem was something that locals dearly hope we’ll never hear about again: turbidity. That’s the official word for the fact that Helene’s sheer impact had turned the reservoir’s clear waters into brown muck.

Two numbers show the extent of this problem. Turbidity is measured in units called NTUs. Prior to Helene the North Fork’s water was usually at 1.5 to 2 NTUs before the plant filtered and treated it. Just before its lines collapsed on Sept. 27, it registered a stunning 79 NTUs. By the time the new line was connected it had dropped down to the high 20s.

Now most water plants in the state could treat water that murky, through systems that collect and remove sediment before further processing. But the North Fork is, on many fronts, not typical. Because the reservoir was unusually pristine, its plant could practice direct filtration, treating and filtering water right from the lake without the need for major sediment removal first. This had saved city government the need for $100 million in additional treatment systems. In the aftermath of Helene it also became a major problem.

One thing that had changed from previous water crises was, however, far more active communication. Water department spokesperson Clay Chandler became a common sight at the post-disaster briefings, and detailed what was happening to the water system with a depth — often complete with video and photos — that the public hadn’t seen before.

It was a marked shift from the incoherent invisibility that marked city communications during previous water crises. In parsing Helene’s aftermath we now have far more information about what happened than we did in the 2019 and 2023 disasters. This also explains one reason why officials’ communications about lead amid the lifting of the boil water notice later went over so poorly; locals had become used to better.

It’s hard to describe the degree to which a city relies on running, potable water. Humans die without water, of course, and that’s before we get to the need to cook, wash, clean, flush toilets, put out fires or a thousand other things. The collapse of Asheville’s system was a disaster in its own right, one that had the potential to be as devastating as floods and winds.

In the days after Helene the need was dire. Stunningly, after the 2023 system failure city officials hadn’t bothered to store any water reserves, let alone make plans to distribute them in a crisis. In one of her first post-Helene interviews, with Blue Ridge Public Radio on Sept. 30, Manheimer said city hall hadn’t bothered to do so because such emergency planning was the county’s responsibility and they wanted to “stay in our lane and do our job.” No, I am not making that up.

County government only had one back-up water supply. Brilliantly, it was across the flood-prone Swannanoa River. Despite a nearly half billion dollar annual budget, over 1,600 employees and predictions days before the storm hit that the Swannanoa would reach record levels, no back-up reserve was created in a less vulnerable spot.

While governments failed spectacularly on this front locals stepped up, drawing on their own water supplies and organizing distribution. Some of the more community-focused breweries drew upon their reserves of purified water. Contrary to some stereotypes flung around after the storm, people throughout Western North Carolina had prepared. That formed the foundation of a massive mutual aid response that averted untold misery. But getting running water to prevent a major health crisis and deal with the storm’s aftermath still remained a serious challenge.

All this meant that there was a real, desperate need to get some water, any water, flowing. So in the days after Oct. 10 the Asheville water system started pumping again. But this water wasn’t going through the usual treatment plant. Instead it was murky, direct from the reservoir and doused with chlorine.

The whole system was under a boil water notice. But it came with a host of caveats, from not showering with any open wounds to the need for additional filtering to only using it in certain dishwashers.

For simplicity’s sake, and out of an abundance of caution, the Blade recommended that this water be used only for flushing. All the information that has come out since has only confirmed that was a solid decision.

While much of the public’s attention was focused on the woes at North Fork, the storm had done massive damage elsewhere too. Helene’s hammer blow also devastated the system’s aging lines. While a heroic repair effort by workers on the ground had mended things enough for it to resume operation, there were still a lot of uncertainties and emerging crises.

One thing that had fallen by the wayside were treatments of anti-corrosion chemicals. These produce a layer within pipes that prevents lead and copper, especially from older lines, from leaching into the water. Known as “scale,” it can take years to build up.

This is especially important in Asheville because the area has a particularly old housing supply. By some estimates over 60 percent of the homes and apartments in the city were built before 1988, when using lead in plumbing was far more common.

During this time the turbidity at the North Fork reservoir remained stubbornly high even as boats doused its waters with the kind of coagulant chemicals usually used inside the treatment plant in an effort to tamp down the sediment.

But with the help of the Army Corps of Engineers, system workers had build a miniature replica of the plant’s filtration and treatment. With this they could run reservoir water through and see if it would damage the plant. Starting on Oct. 30, they found that they could treat some water without it doing so. For the first time in over a month, treated water re-entered the system. This included anti-corrosion chemicals, particularly zinc orthophosphate.

Over the coming weeks the amount of treated water steadily escalated. While the turbidity levels remained above the single digits they hoped for, according to Chandler the type of sediment they were dealing with had changed for the better.

“We discovered this after running test of the water through a mini-pilot plant whose filtration systems are the same as the North Fork’s,” he wrote on Nov. 21 in response to questions from the Blade. “In the immediate days after the storm, North Fork’s reservoir had a different type of turbidity than it does now. It initially was very thick and muddy. Now, it has a sort of fluffy texture, making it easier for our filters to handle.”

Previously city officials had estimated that it’d be around mid-December before full, potable water returned. That’s the time they predicted it would take for the Corps of Engineers to construct a portable sediment filtration system to decrease turbidity in the water before North Fork’s plant could readily process it. But as heavier sediment settled to the bottom it turned out their existing equipment could handle more than they’d thought.

“Earlier in the repairs of the water system, the impression was that it would take turbidity dropping well into the single digits before the North Fork plant could use its direct filtration system without damage,” Chandler added. “However, it seems like the existing filtration system was able to process higher turbidity water than originally anticipated.”

This moved the timeline considerably forward on returning potable water to the system. In preparation for this the wide array of parties testing Asheville’s water — the water department, the state Department of Environmental Quality, the EPA and outside labs — escalated a barrage of testing already underway. Mostly these were for bacteria and the kind of metals (especially aluminum and manganese) that hung out in that turbid water. But tests were also taken from 25 then-closed schools around the area between Oct. 17 and 24, after the untreated water had started coursing throughout the system. On Nov. 8 the results from those finally came back.

That’s when they found the lead.

‘There is no safe level of lead’

Crews reconnect a water main in the Haw Creek area, Oct. 15. Helene caused extensive breaks along the Asheville system’s long-neglected lines. Photo from city government

The Nov. 14 announcement that lead had been found in seven of the schools served as a stark reminder of just how vast the damage to Asheville’s system was. By that point our area was close to two months since stormfall, and the aftermaths of it were still being discovered.

Follow-up tests of the North Fork’s waters, and along the water distribution lines, didn’t find any lead there. That was one of city officials’ justifications for lifting the boil water notice. But that did not mean the danger was gone.

“What has been keeping our older homes, businesses and schools from having elevated lead in their water is that, over time, pipes and fixtures have developed a thin protective coating that prevents the direct contact of water with the metal,” Wasileski wrote on Nov. 19. “Any small breaks in this protective coating would now enable water to come in direct contact with lead metal in the pipes and fixtures, and cause this lead to corrode and leach into the water flowing through home plumbing.”

She blasted city government’s Nov. 18 announcements, particularly their communications around lead, as “grossly insufficient.”

“Advice on flushing alone is poor public policy,” she continued. “I understand that it is very important not to cause a panic. Yet clear and effective communication and widespread testing will ensure that there is not a second crisis across Asheville and Buncombe County. There is no safe level of lead in drinking water.”

Indeed lead poses a particular risk to those already rendered more vulnerable by the storm, including children.

Among experts in water systems Wasileski is far from alone in her concerns. The Blade asked Andrew Whelton, a professor of civil engineering at Purdue University who specializes in water systems, for more insights into Asheville’s situation.

“The lead may be due to the destabilization of the scale and switching between waters,” he said.

He didn’t find it surprising that testing had not found lead in the source water and distribution lines, as a break in corrosion treatments generally does the most damage in homes, businesses and community buildings like, well, schools.

“When you shut off the corrosion inhibitor it will affect the lines the city doesn’t own.”

Whelton also warned that there may still be other issues on the horizon if the “scale” in Asheville’s lines has, as feared, suffered significant damage.

“Generally scale builds up over time and by shutting off the corrosion inhibitor you sometimes don’t have an immediate change in the drinking water. It may take time.”

“The lead in water issue is a treatable issue,” he continues. “There are certified filters that remove lead from drinking water. Health departments can recommend which ones to buy. These filters are tested against very specific levels of lead, for that reason you want to know the minimum and maximum amount of lead you may see.”

Like Wasileski, Whelton believes it’s vital that Asheville’s water department and the other agencies working with them conduct extremely extensive testing, for lead and other chemicals they might not usually check for.

“The incident in Asheville was more severe than just a standard hurricane,” he tells the Blade. “Generally when you have such severe infrastructure damage you don’t just treat it as a standard disaster. You throw the kitchen sink at it, then you back off if you find there’s not as much damage as you thought there might be.”

It will likely be another week or two, at least, before we have firmer information about the extent of scale damage and the resulting lead contamination throughout Asheville’s system. Like everyone, we really hope that scale held.

Notably the city water department’s own advice now contradicts Manheimer’s assertion that the need to flush water through the pipes was how just things had been before Helene, noting that it’s a “temporary measure” to be used “until more investigative lead and copper sampling” brings clearer answers.

Sadly the city’s messaging on this is still far too rosy, with its last daily information sheet, on Nov. 29, still emphasizing “normal usage for consumption” before its laundry list of the risks of consuming lead.

As it has for most of a month now, “no contamination” followed by an extensive warning about one of the ugliest contaminants one can find in water doesn’t exactly create clarity on this front.

Using the return of potable water as an excuse to dismantle the vast majority of local governments’ care and water distribution sites on Dec. 2, at a time when 60 percent of those on city water face a considerable risk, was even worse. As it did before the disaster, the upper ranks of city hall just do not care about the suffering their actions inflict on the wider community.

Sadly, this resembles the similar “back to normal” approach to that they used with the pandemic. Already, among some of the same decision-makers who made the impact of the storm far worse, Helene’s already being written off as a singular event rather than a potential harbinger.

The fact is that we’re not out of the water crisis yet. The situation we’re currently in is far better than what we faced a few weeks ago or, god forbid, right after the storm. It is still not without very real danger.

A massive natural disaster, fueled by climate change, smashed Asheville’s water system. Years of neglect and corrupt policy left it far more vulnerable — and the damage more extensive — than it had to be.

A rush back to the status quo is now glossing over some very real risks rather than facing them. While horrifying, this approach is no doubt familiar to locals who’ve lived here for any length of time. This is Asheville’s business as usual. And, as usual, it is the people on the ground who will pay the price.

—

Blade editor David Forbes is an Asheville journalist with over 18 years experience. She writes about history, life and, of course, fighting city hall. They live in downtown, where they drink too much tea and scheme for anarchy.

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by our readers. If you like what we do, donate directly to us on Patreon or make a one-time gift to support our work. Questions? Comments? Email us.