Routs, truces, clashing views and more as Council closes out its year with the latest chapter in the development wars

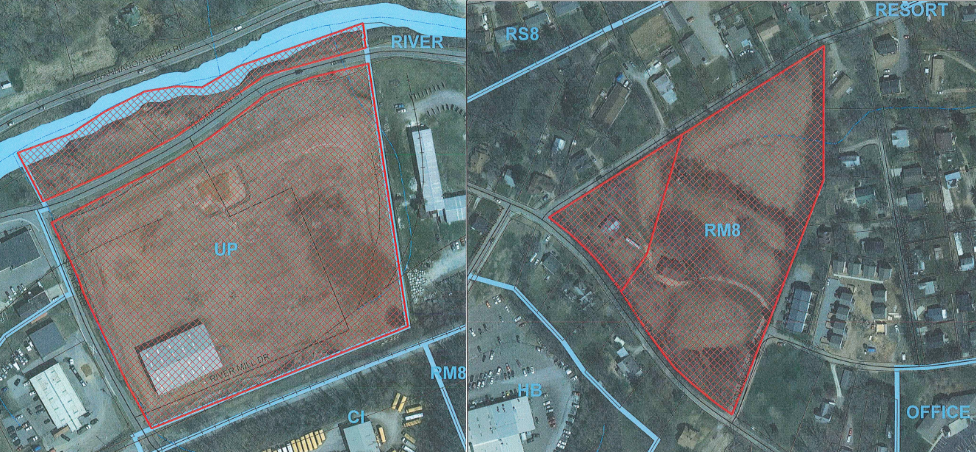

Above: the future sites of the River Mill Lofts and Hazel Mill Roads projects, on the city’s development maps.

Historically, few things pack Asheville City Council chambers like fights over development. Our city’s not alone in this, of course. Physical space — what it looks like, who lives on it, how much it costs to live in — is at the core of any city’s future and identity.

Especially as the city’s seen rapid growth over the last two decades, few other municipal matters get the crowds out like a new development or a change in rules that people believe will change drastically (usually for the worst) where they live and work.

And make no mistake, for all the talk about cooperation, development fights are usually exactly that. They come from the fact, after all, that cities can never do everything for everyone at once. Development follows certain patterns (dense or suburban, for example) or it doesn’t. It will be easier for some populations and not for others. Neighbors will have very specific ideas of what they want built in their neighborhoods and sometimes even who they want living in those structures as well.

On Dec. 9, Asheville City Council faced its last meeting of the year promising not just one of these development fights, but potentially four. Like with any conflict, the results contained a few surprises, some delays and even, in some form, a stab at at truce.

The fires last time

City government passed the Unified Development Ordinance in 1997. However, many on the current Council and higher-level staff have said publicly that they believe many of those rules are outdated, made by a different Council for a different Asheville in a different time. At the very least, it’s not uncommon for developers to propose projects that don’t easily fit within the UDO’s rules, meaning they have to go before Council to get the zoning changed or special exceptions tied to meeting certain conditions before a project can proceed.

That’s meant that over the years many controversial development decisions end up in Council’s lap as Asheville attracts more attention and development. In some cases, like with the Downtown Master Plan or the recent shift to a different type of zoning along Haywood Road, city government’s tried to cut some bits off this particular Gordian knot by passing overhauls or new guidelines for specific areas.

In the meantime, the same attention that leaves Council with developers asking for an exception to the rules has also driven the cost of housing through the roof.

While famed for denser areas like downtown or the core of West Asheville, our city’s not particularly dense, even by North Carolina standards. Out of 18 cities in the state with a population over 50,000, Asheville ranks 10th in density, behind places like Charlotte and Wilmington that are generally thought of as examples of sprawl. Functionally, most of Asheville is more suburb than metropolis and that’s what people who live and own property here are used to.

At the same time, the politics of the city have shifted. While Council elections are nonpartisan, certain alliances and factions do dominate. From 2005-10 a particularly big change happened. It may seem odd to observers used to a Council composed largely of Democrats from the party’s progressive wing, but nine years ago conservative Democrats and Republicans held a majority. As recently as 2009, a third of Council was Republican.

Back then that meant that progressives, whether more concerned about neighborhood character or affordable housing, were usually in alliance, often against corporate developers and their projects (the scuttled Parkside development was a major example) that they perceived as both unaffordable and out of keeping with local character.

But starting with the 2009 elections, progressives nailed down a majority and have kept it ever since. Naturally, divisions within their own coalition started to emerge. Neighborhood activists generally wanted development done in small doses and finely tailored to fit their perception of the existing area’s character and asserted that problems with traffic and aging infrastructure makes many areas inappropriate for density. Those pushing for affordable housing put forth that Asheville needed way more density and way more affordable units if the city wasn’t going to increasingly exile anyone outside of the upper-middle class or the wealthy. As these two goals can’t both happen, the last four years have seen major clashes between the two views over a number of projects.

Like any factions, especially in local politics, there are exceptions and overlaps. Affordability advocates sometimes balk at particular developments about concerns like infrastructure and neighborhood activists occasionally support denser housing, especially if it’s being built somewhere else. But the tension between these two views has left the shape of the city’s future development deeply chaotic, with neighborhood opposition often fierce enough to delay or scuttle attempts at denser development.

However, in the meantime the city’s affordable housing situation has gone from “not great” to “major crisis” with Asheville making lists as one of the least affordable areas in the country as costs rise far ahead of stagnant wages and the affordable housing developments that do open up are bombarded with hundreds or even thousands of inquiries. The current Council’s also weathered these development battles with their electoral majorities largely intact, even after they voted to raise property taxes last year.

While there’s still a major debate about how much funds city government’s willing to put into programs like its affordable housing trust fund, the housing crunch has meant that Council has, in recent years, the need to approve or even incentivize almost any increase in the housing stock, even developments that weren’t affordable.

So earlier this week, the agenda had three major developments, all facing some degree of neighborhood concern or opposition, and a major change to the UDO allowing more dense housing in commercial areas.

The ‘radical’ rout

That change came up first. Essentially, the new rules allow residential development in areas right now zoned for commercial uses, even allowing them to considerably increase — quadruple or more in some cases — the allowed density if 20 percent of their units offer rents the city considers affordable.

“Some have asked if these numbers are too high,” planner Blake Esselstyn said in his presentation to Council, but he pointed out that some existing apartments along Merrimon Avenue and the River Arts District fit neatly within the density the new rules allow. “Staff feels that these are appropriate for the corridors.”

Staff worked since last winter crafting the ordinance and the issue went through multiple committees, even getting pulled from the agenda this fall for further consideration.

Council member Gordon Smith, the overhaul’s main proponent on Council, endorsed the proposal as a win-win to deal with the housing crunch allowing denser development, especially if it’s affordable, in areas where the infrastructure’s already built.

“This is a really important night,” Smith said, calling the measure “the leading edge” of a larger strategy to tackle the city’s affordable housing problem. “Ultimately this is about thoughtful growth in the city of Asheville. Knowing the need for affordable housing is so great, how are we going to accommodate the density necessary to solve the problem. We know that 31 percent of Asheville’s workers are making less than $25,000 a year. The average wage for accommodation and food service workers is about $16,000 a year.”

“This Council is committed to economic mobility for all its citizens and without affordable housing that’s not available to the folks I just mentioned,” he continued. “Of the 1,140 apartments that have been approved since 2012, 43 were affordable to people making 80 percent or less of our area’s median income.”

Smith’s previous major proposal to overhaul the city’s development rules to allow more density came up in 2010 and its fate presaged some of the battles to come, with neighborhood activists calling it “undemocratic.” Their opposition meant that the changes that were considerably scaled back from the original proposal.

The current proposal was necessary in part, Smith said, because despite the city’s reputation, “creative people can’t afford to live here.”

But if there was any opposition this time around, it didn’t show up in Council chambers and the result was more a rout than a battle.

“It’s a lot for people to take in,” Council member Cecil Bothwell said. “But I’m quite satisfied that this is a workable plan, it’s a rational plan, it’s going to help us increase density.”

One of the main concerns in public comment on the issue came from Kim Roney, who said she supported cast doubt on the criteria the city uses for its affordability rates.

“The median income is listed at $39,000 but most of the people that live in my neighborhood and that I work with make half that,” she said. “I don’t know if this is the right time but I wanted to ask Council to consider the percentage of affordable housing that we’re putting in any sort of density, because we need more of it and we need it fast. Otherwise the people who make our coffee and our babysitters won’t be able to live here.”

Rich Lee encouraged Council to pass the changes as “a great first step. It’s imperfect and it’s not going to address the problems of the truly low-income. But I believe this is the right way to consolidate apartments along the corridors to protect the cores of neighborhoods.”

“It’s really heartening to hear folks get up and encourage us not just to take this step but to take future steps,” Smith said. “This invites all those private developers to the table to say ‘we want those partnerships to work.’ These are places that are close to business, close to transit.”

On Council too, support for the change was unanimous, something that even seemed to surprise Mayor Esther Manheimer, who said, just after the vote “well, we’ve radically changed the UDO.”

Neighbors and neglect

But if that battle was a no-go, the next one more than made up for it, with a proposed housing development facing major opposition from the surrounding community.

At issue was the proposal by developer Bob Grasso to add 104 units, mostly one and two-bedroom apartments, in a complex on Hazel Mill Road in West Asheville. Eleven units will be affordable housing and Grasso will provide bus passes to each unit as well as $14,000 to the city to help construct additional sidewalks in the area.

“This is a design that’s responded to the concerns expressed by the neighborhood,” he told Council. “This shouldn’t significantly impact the traffic… we’ve tried to build all the important aspects of what would make this a really exceptional project for the city and for the neighborhood. We’ve provided amenities, we’re trying to make it as livable as possible.”

As for the opponents, “there are people who don’t want change. I’ve tried to be sensitive to what their concerns are.”

But to many of the neighbors the area’s long infrastructural neglect — marked by a lack of traffic calming measures, sidewalks and easy access to transit — leave it ill-equipped to handle that increase in population and the additional cars the new residents will bring.

“Most of these people are against the project based on the infrastructure challenges we face,” Valerie Martin, speaking on behalf of a group of neighborhood opponents, said. “This particular corridor hasn’t seen any significant infrastructure improvements over the last 50 years. We haven’t seen the improvements to match the development we’ve seen over that time.”

Before her remarks, about 15 people stood up to show their opposition to the development. She added that the need for sidewalks was already there and that residents already have problems using mass transit. “Traffic already feels unmanageable, so any increase is significant to us.”

“A lot of us support infill and are in opposition to sprawl,” she continued. “We see the wisdom in higher density in urban areas, so we’re not opposed to higher density per se, but we need to support that” with better infrastructure.

In addition, state law allows surrounding property owners to file a protest petition against a proposed project, meaning it must gain passage by a supermajority of Council members rather than just needing the usual four votes for passage. Historically, these have been a major way for neighborhood activists to halt a development even if a majority of Council supported it. In this case, that meant five votes. One of the neighboring property owners, Harry’s Cadillac, had hired an attorney from the Van Winkle law firm that Manheimer also works for, meaning she had to sit out this issue to avoid a conflict of interest.

The public comment portion of the meeting was dominated by opponents of the project, with most of the objections based, as Martin summarized, around a lack of infrastructure.

“There’s been expansion in the form of town houses and Section 8 housing,” local property owner Rich Steinholm said. “Those units have significantly negatively impacted the ability of people with vehicles to get into the area. This project will only exacerbate that…I am concerned it makes the neighborhood less attractive to people who want to live there.”

“As an individual, I don’t want to see something like this across from our house,” neighbor Steven Slack said. “But as a member of Asheville I’m in full support of its affordable housing initiatives. But are we going to approve affordable housing without improving the livability of the surrounding area?”

“With this increased density my concern is for the neighborhood and the people that live there, there already is too much traffic on Hazel Mill,” he added. “I’d like to ask for you to consider an improvement to the infrastructure of this area if this project is approved.”

A number of the opponents said, like Martin and Slack, that if Council did pass the project, they wanted significant improvements before Grasso builds the development in 2017.

Bridget Nelson noted that with the rates Grasso is charging “I don’t know if we want to be jumping up and down and cheering because that’s still not in range for a lot of people.”

However, one of the opponents, Nathan Merchant, said he didn’t just object to the lack of infrastructure, but the type of people who would move into one and two-bedroom apartments in the affordable and workforce price range.

“We’re concerned that the quality of the customers of these apartment complexes will not beautify the neighborhood, will not have a vested interest in the quality of the neighborhood,” he asserted. “What we would like to see more sustainable housing. There’s no reason you couldn’t have affordable three-bedroom apartments that would have families that would take care of their apartments. When you’ve got a one-bedroom apartment, the sort of demographic of individual you’re going to get there is not someone who’s going to be interested in glorifying the property. It’s going to have a higher turnover rate, it’s going to have more trash.”

Instead, he believes the neighborhood would be better served by 12 to 15 small single-family homes on single-family lots “and we would have no problem with that.”

Council ended up, due to the housing crunch, supporting the project, but some noted they believed the neighbors had a real point about the lack of infrastructure in the area.

“It appears to me that we absolutely have to build those sidewalks if we approve this development,” Bothwell said.

Council member Chris Pelly agreed. “This is an example of two of the demands of the city coming into conflict. We heard earlier about the need for affordable housing. At the same time we’ve also committed ourselves to great mobility. You’re hearing from Council tonight that we’re also committed to trying to ameliorate the impact on the surrounding neighborhood.”

Vice Mayor Marc Hunt noted that it wasn’t just Hazel Mill; many neighborhoods around the city struggle with similar problems.

“This is actually an extraordinary moment where we have people in a community thinking creatively, expressing community-wide needs and views regarding how a project might fit in,” he said. “We’re always going to have a challenge of the pace of infrastructure versus the pace of development.”

“I hope people understand the challenges we face when it’s suggested ‘please don’t allow development in certain places until you bring infrastructure,” he continued. “Well, we’ve got deficient infrastructure for projects like this all across the city and it’s just impossible for us to act first with infrastructure and predict where the next development is going to go.”

Despite the opposition, Council voted 6-0 to move Grasso’s project forward, but followed it with a resolution — passed by the same margin — by Pelly to give the area high priority for sidewalks in the city’s next budgeting cycles.

Down by the river

The next development didn’t have a large population of surrounding residents in arms quite. But the River Mill Lofts, slated for a portion of Thompson Street near former industrial sites around the Oakley neighborhood, highlighted how the city’s pushing for more development in that area and concerns from some nearby residents.

The project would include 254 units, with 18 of them affordable, along with a small amount of retail space. Planning Director Alan Glines told Council that as a dense, mixed-use development, it met a number of the city’s goals and noted “not every project can be a complete answer to a community every single time all the time. This is one parcel; there are many parcels up and down the corridor.”

Albany, Ga.-based developer Pace Burk promised that in addition to the affordable units he was already offering, said the project would bring much-needed residential development along the Swannanoa River.

“A lot of people think we’re pioneers; we take a few risks on projects others aren’t interested in doing,” Burk said. “But we believe a lot in this area. The river corridor is the most exciting part of this whole project.”

Burke also said he wanted to work with the city to take advantage of an incentives program and possibly increase the number of affordable units he’ll offer before the development breaks ground.

“We’re committed to that program, we’re committed to going beyond,” Burk said. “It opens up to a larger rental pool because right now everyone’s going after that small pool who can pay $1300 a month. That’s where everybody’s going.”

“We’re all really hopeful there’s going to be a lot more of this going on in that area,” Smith noted when it came to more commercial and residential development. When he asked what specific percentage of affordable housing Burk was shooting for, the developer declined to specify, saying that his project was still being assessed by city staff to determine what kind of incentives the city could offer.

But he did commit to following through with that process and said his goal is to provide more affordable units than originally proposed as the project is completed.

“You’re speaking my language,” Smith replied.

While there wasn’t as big of a turnout of neighbors objecting to the project as there was on Hazel Mill Road, some nonetheless had concerns about the development and the lack of communication from the developer.

“The people should have been considered on this,” resident Mike Carroll said. “We should have been given a little more information, a little more time.”

Walter Barber, who attends church in the area, was concerned that the increased traffic would create a potentially hazardous situation for churchgoers.

“I live on Stoner Road and I’ve lived there nearly all my life,” Marie Carroll said. “Nobody thought about infrastructure when it was just concerning us.”

“I wish the developer had considered the community,” she added. “Come to us and sit down. If we’ve got concerns maybe we can work it out together.”

Neighbor David Edney had a similar concern.

“There’s likely some fences that need to be mended here,” he said. “I think this area has probably been neglected somewhat, from an infrastructure perspective.”

“I would recommend that the way to win good neighbors is to come, knock on the door, ask if you can come and be part of their community,” he added. “Please bring people to our community. It sounds like these folks have good intent.”

Dana Davis cautioned Council to remember that their goal for developments was 20 percent affordable housing, not seven percent.

While Pelly cautioned Burk to be more proactive in communicating with the neighborhood, Council once again passed the development unanimously.

More on the horizon

Originally, even more potentially contentious developments were on the agenda, but Council agreed to delay a 305-unit apartment project on Fairview Road until Jan. 27 and the Greymont Village apartments on Sardis Road until Jan. 13, so the coming year won’t see a pause on this particular political front.

“You’re going to see a lot more,” Smith noted early in the meeting, talking about attempts to increase density and affordable housing. And while the politics and dynamics around development have changed throughout Asheville, Council chambers will witness a lot more fights about the shape of the city.

—

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by its readers. If you like our work, donate directly to us on Patreon. Questions? Comments? Email us.