The State of Black Asheville, Dwight Mullen and the call for consequences for this city’s institutions — and their failures

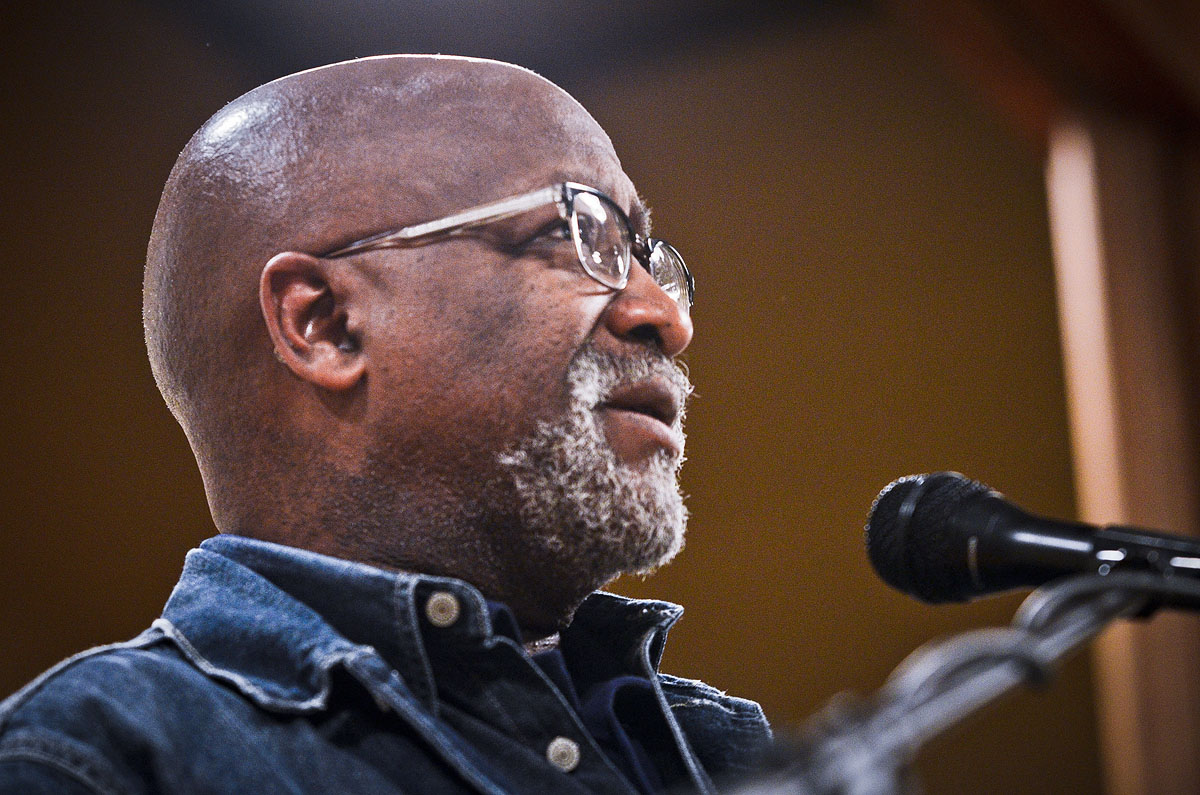

Above: UNCA professor Dwight Mullen, speaking at a Martin Luther King Day event at Kenilworth Presbyterian. Photo by Max Cooper

“It would be considered a state of emergency if you were seeing the same outcomes with white people,” UNCA Professor Dwight Mullen says, sitting in his office. “It seems to me that all you have to do is take off racial blinders for people to see how serious it is in the African-American community in Asheville regarding public policy outcomes. The disparities are shocking, and they’re more shocking than they used to be. They used to be shocking, and now they’re beyond that.”

By now, Mullen knows those numbers well. In 2007, Mullen, a political science professor, assembled a group of students to begin the State of Black Asheville project . Housing, family income, incarceration rates, healthcare. All show a deep divide between what African-Americans here see — across class and education lines — and the outcomes for the city’s majority white population.

“Can you imagine Mission being ranked one of the nation’s top hospitals if it headlined with African-American mortality and morbidity rates? It would not happen.”

He sees a disparity, too, in the reactions of most of Ashevillians to this state of affairs, year after year. An incredibly low rate of African-American students proficient in math, for example, is a cause for more brainstorming rather than being regarded as a serious problem.

“I’m fine for people coming up with new ideas and brainstorming. But we don’t talk brainstorming when I’ve messed up my budget or when the building has caught on fire and we don’t have facilities, or when there’s a sexual predator on campus or when the coach has decided that he wants a winning state team. There is no emergency that matches that.”

As Asheville, a city with its own harsh history of —and current issues with — segregation, has seen demonstrations, vigils and protests in the wake of the refusal to indict police officers for the killings of Michael Brown and Eric Garner Mullen, always active, has seen an increasingly high profile. On December 13 he delivered the commencement address for UNCA, and the next day was a featured speaker at a well-attended “Black Lives Matter” event at Hill Street Baptist Church. He spoke at one of Asheville’s main Martin Luther King Day events and recently his efforts as an educator and with the State of Black Asheville were featured in the Asheville Citizen-Times. “I’ve been giving a lot of speeches,” he noted with a chuckle in his January remarks.

But he also notes that even for the most committed local activists seeing the same results, year after year, can be disheartening.

“You can’t help but say ‘what are we going to about it? This is unacceptable,” he tells the Blade. “The numbness comes year after year when the institutions keep producing it and there is no accountability.”

For example, he says, in both housing and healthcare federal, state and local governments measure differences in racial outcomes but don’t force institutions to reform if those differences continue.

He notes that the education gap in Asheville City Schools, for example, is getting worse over time, not better. “You can’t expect disparities to close in education without early childhood education.” But all of those programs have been cut.

He says the school board and superintendent have “their hearts are in the right place,” they’re aware of the problem and they want it to change. But “you can’t just visit once or twice a year, like City Council does, and expect everyone to be on the same page.”

Feet to the fire

Furthering the problem in the local government arena, as Mullen sees it, is a divorce between the power of elected officials and the day-to-day power wielded by appointed bureaucrats.

“The accountability of the ballot box is not available,” he says. “It’s almost as if the elected officials — and this is how it’s designed — are totally dependent upon the professionals. But the assumption is that the professionals are being held accountable.”

Nor is his own institution exempt. Like Asheville City Schools, UNCA was under federal supervision in the early 1980s to correct racial disparities, to have a minimum percentage of faculty, students and graduates who were African-American.

“Not a single predominantly white institution, including UNCA, met its goal. Ever,” Mullen remembers. “Once again, we have standards, but no one is ever held accountable.”

“Twenty two percent of the college-bound, high school graduates are African-American in this state, so it’s not like the pool is not there, even though we have this crazy disparity nonsense is happening,” he continues. “One out of every five of these students is African-American.”

“In UNCA it used to be that they were ‘color blind,’ this is around the turn of the century, around 2000, so we’re not paying attention, then it went to ‘we can’t use race in our applications,’ which the Supreme Court said you could. Now it’s money, that we just can’t compete for scholarship money to bring in the students we want.”

In each of those cases I just find them wanting.”

The liberal problem

One important thing, Mullen says, is for the public to understand that blatant bigotry or hatred from individuals isn’t necessary for racism to continue, especially in Asheville. “At UNCA,” for example, “there’s never been a malevolent attitude in the administration.”

But the issues continue nonetheless. “The administration has done hard work in diversifying the faculty. However, when it comes to the student body, year after year, it doesn’t meet anybody’s expectations.”

There’s a lesson in that, Mullen notes people occupying positions of power in institutions don’t need to be evil to further racist outcomes that they then need to be held accountable for.

“King said the same thing: really the problems he ran across, over and over again, were not with the conservatives and it wasn’t with overt racists,” he says. “He said the major break on it was with liberals, folk who didn’t see the need to go into emergency mode, who said ‘give us time,’ who said ‘why can’t you wait? We’re doing the best we can.’ He said that was really the biggest problem.”

Racism is “at the informal level now. It’s de facto, it’s habit, it’s custom. I don’t know how many time you have to say to folk: you have to look at your selection methods, because year after year ‘gifted and talented’ students are dominated by white girls and ‘behavioral disorders’ are dominated by black boys. One goes to college, one goes to jail. How many times do you have to say it?”

The same thing applies to the economy: “no one is tying race or class or gender to the agreements that bring these [businesses] into town. That’s very common in other places. No one is holding these institutions accountable for the conditions they leave the community in if they decide to leave.”

That’s the direction accountability would take, he believes. “That’s a huge thing, when you start talking about all the hotels downtown paying living wages and expected to meet very basic standards of employment.”

In Charlotte, he notes, parents became angry enough “that they threatened the funding of the gifted and talented program,” he says with a smile. “All of a sudden they found gifted and talented African-American kids.”

A call for consequences

Back in December, Mullen stepped up to the pulpit at Hill Street Baptist Church. The two-hour long service saw over 300 people in attendance, including Mayor Esther Manheimer. Multiple local leaders spoke, including Mullen’s UNCA colleagues Darin Waters, a history professor, and political science professor and activist Dolly Jenkins-Mullen (also his wife). A brief Mountain Xpress report headlined that “Black Lives Matter service remembers, searches for answers.”

What was said, other than a few brief quotes, got a bit less attention. But in Mullen’s case, he delivered not just a memorial, but a direct call for consequences and an indictment of a lack of accountability in Asheville.

“Do you know why we collect data? Because nobody else does,” he told the attendees. “There is no place you can go to find out what’s going on with African-Americans. There is no central place where you collect the names of the killed, the murdered.”

“This is my home, Asheville is my home and because it’s my home I have a right to call it out when it’s wrong,” he continued. “That data is the indication of when it’s wrong.”

But while “we can talk about what’s wrong,” his bigger interest, he said, is in finding out “what we are going to do.”

The important thing was to start shaking local institutions, because “when they’re not here we’re missing a major component of fixing this problem. You can put forward all the effort you want, but if the institution doesn’t move, it’s just a matter of time.”

For his part, he was committing UNCA to some of these gaps, using its resources and skills, “despite the fact that I don’t own it” because right now “we are not part of the solution to those problems.”

“The rates at which we are not educated, the rates at which we die and are getting sick, the rates at which we don’t own homes, the rates at which we are paid below a living wage are worse than when Jim Crow ended,” he said. “That’s what happens when your institutions don’t move: you find yourself in the same place.”

“When we figure out the black lives matter, the question becomes: how do we make them recognize that?” But “that is a challenge that can be refused.” Indeed, he sharply criticized outgoing UNCA Chancellor Anne Ponder for failing to more meaningfully make progress on the college’s diversity issues. Clearly, he added, solving this was not a priority for the university. “It wasn’t her mission.”

“That’s what happens when you live in a small town,” he said with a chuckle. “At some point you start speaking truth to power and you tell people what the power said.”

“The hardest part is not collecting the data,” he warned. “The hardest part is not giving speeches to them, the hardest part is not following up, the hardest part is what will you do if they refuse.”

“Don’t you understand why Mission will not do any better? Don’t you understand why the major employers will not change the wages? Don’t you understand why they won’t give you credit? Don’t you understand why young black men are four times more likely, even in Asheville, to get arrested than anybody else? Don’t you understand why they do that? They do that because they know nothing is going to happen to them.”

Those words received a standing ovation.

“If you don’t hear what I say, look at those pictures. That’s your family you’re looking at. Those are your neighbors. That’s your friends. We can’t sit down and let these institutions do nothing about it.”

Stepping up

It’s easy to see events in the public square, like marches, protests or community conversations, as suddenly emerging onto the public stage. At this past summer’s State of Black Asheville conference, as the attendees broke into groups in the rooms of the YMI, it was a scene of extnesive planning and organizing, in areas from criminal justice to child care to access to better food and healthcare, and the attendees included many local leaders and volunteers who would play a role in the events and protests later that year. That mindset, Mullen believes, is an ongoing strength of the local African-American community.

“There’s always a relatively high level of activity in the African-American community on certain issues,” Mullen says, though challenges remain as groups try to endure over a long enough haul to make a dent in these entrenched problems. “But what I find that these are citizen volunteer groups that are not even non-profit status, they struggle with administration.”

Still, he feels that African-American activists, like any community, can too often see their weaknesses more easily than their strengths.

“Any community tends to be its own harshest critics, and that stretches across ethnic and class lines: the people you know best are the folks you can criticize best,” he adds. “One of the things we don’t give ourselves credit for as a community is unselfish use of time, just putting in hours. Nobody’s paying these folks to come out of the conference on State of Black Asheville, no one’s paying these folks to use their off hours on the weekend or their retirement time to go tutor in the Asheville City Schools or to give support to a health fair.”

“No one’s talking about the times the one or two professional African-Americans you’ll find in the banking system are there and advocating for loans to be given that demonstrate the institution’s commitment or soliciting funds from institutions for activities. We lose track of those energies, but there’s a fair amount.

“There’s crazy volunteerism in Asheville, so I’m not so quick to criticize our community as I am to criticize the institutions that are tasked with this stuff.”

Because of that, he says, he’s more interested in directing communal ire and the desire for change at higher-up decision makers in institutions. For example, “instead of nailing teachers to the wall, we need to look at the resources teachers are dealing with.”

In healthcare, having African-Americans familiar with their community throughout all levels is necessary. “No matter where you go, you can see members of all the communities. They used to call it representative bureaucracy.”

And that, he emphasizes, is where racism — especially in Asheville — often dwells, not at the formal legal level or with violent vigilantes, but with administrators, bureaucrats and what’s not said.

‘Democracy means nothing without accountability’

About a month after his Hill Street address, Mullen again took the stage alongside Waters and local civic leader and civil rights veteran Marvin Chambers for a packed MLK Day event at Kenilworth Presbyterian (Mountain Xpress reporter Carrie Eidson posted video of much of those remarks).

“I was not a King advocate,” he admitted. “ When I was coming up in Los Angeles, to talk about non-violence in the Los Angeles Police Department; that was an oxymoron. You can lay down in front of them if you want to.” At the time, he found what the Black Panthers were saying about self-defense made a lot more sense. “My father was from Mississippi. I’ve never known a Mississippi man that didn’t own a gun. Because they understood what the real deal was when it came down to protecting your family.”

But during his undergraduate days, he spent time with civil rights leader Ralph Abernathy. Then, in his tenure at UNCA, he learned more from leader and legislator Julian Bond and historian John Hope Franklin.

“They, all three of them, talked to me in the terms of warfare,” Mullen remembered. “They talked to me as though they had been on a battleground, that they had fought in the street, bled and died, to win this war and they were proud of it.”

“I remember Ralph Abernathy talking about holding Martin Luther King as he died,” he continued. They left him with a question not of fighting a war, but “will you win the peace?”

During Reconstruction and again in the aftermath of Civil Rights, based on the very outcomes State of Black Asheville measures and the killings that by that point had sent hundreds in Asheville into the streets he asserted the peace had not, in fact, been won.

“Dismiss progressive. Don’t think progress and evolution, think eras of history,” he said, and wanted the audience to understand that struggles can go the wrong way as well as the right one. “Those parallels get eerie with having lost Reconstruction, the Supreme Court begins hollowing out its decisions regarding segregation.”

Now, he said “you have a wonderful shell, but where is its substance?” So poverty rates didn’t decrease, sometimes even increased, and de facto segregation in many areas remained.

As for violence, he targeted the events going on nationally, but also statewide and locally, noting the case of A.J. Marion, an Asheville teenager shot by an APD officer in 2013. The State Bureau of Investigation cleared the officer, who has never been identified.

“All of them resulted in the non-indictment of the police.”

“You start putting it together: the police are killing more African-American men and women than were lynched at the height of the lynching era.”

In response to these problems, he started asking “did we win the peace here in Asheville?” As a political scientist, he began measuring policy outcomes because they indicate where a community is.

“We decide to have schools together. We decide the healthcare system. We decide to live together, housing and neighborhoods and communities. We decide to punish each other together, so we have jails and the criminal justice system. We decide to have transportation networks, all kinds of things.”

“So you ask: are these public policy outcomes the same regardless of race? And that’s where you see the piece being lost.”

But when the idea for the State of Black Asheville began, in the wake of Hurricane Katrina hitting New Orleans, he noted, his students were met with resistance at every turn. “Public institutions of housing, criminal justice and police denied our own students entry. I had students who were threatened, right here in Asheville.” In 2007, they published the first annual report.

“There was not a single public policy area where race was not a major determinant of what happened. Forget class, forget education, forget region of the city.”

At the end of King’s life, Mullen noted, his attention to local areas like housing, poverty and education because that, and the way bureaucrats administered those policies, was where the civil rights struggle was shifting to.

“We lost the peace because of administration,” Mullen said. “That’s where we find the racism of Asheville, and that’s what makes it so difficult to talk about. Because it’s us and we’re just doing our jobs. We’re not taking full responsibility for the outcomes of our jobs.”

To start solving this, he said people needed to not neglect their individual and community relationships and “be a neighbor,” but going forward had to use those relationships. “You start figuring out what people need,” and forming alliances across racial lines to advocate to end those disparities.

“They expect me to say it,” but when others from multiple communities joined in, the call becomes harder to ignore. “Democracy means nothing without accountability.”

“It seems to me that you might and we might, as a city, begin to embrace all those who might be held accountable. Do you know what that means? It’s not just your accountabilty, it’s the accountability of elected officials, it’s the accountability of appointed officials. It’s the accountability of folk across the racial divide. Suddenly, when you see something, that that’s your neighbor, that’s your business too. That accountability is there to ensure that we are all going to come out equal.”

“Let’s use this as an assessment time of our accountability.” And after, people across Asheville needed to use their skills and talents to join together and “restructure” the way the city works. “Maybe we can say not ‘we shall overcome’ but ‘we have overcome.’”

The forever war

“For all intents and purposes, this has been forever,” Mullen tells the Blade. “I remember the first time I worked on a race thing, I was in the fifth grade. The fifth grade, working being part of a white school’s commemoration of Black History Month. They decided I was going to be Eli Whitney. That was an epiphany.”

Here I am, decades later, and we’re looking for outcomes in these public policy things that look like they did when I was in the fifth grade.”

“You can’t help but be discouraged; for my effective lifetime it’s been like this,” he says. “But on the other hand, it feels wrong for me to be so egotistical as to think this revolves just within my lifetime. Because then I’m nullifying what my parents did in Watts and my people have done, no matter where they’ve been, to make things better for themselves.

So “I can’t use that perspective that ‘it was worse and now it’s going to get better.’ I use the perspective of ‘this is how it is and are we defending ourselves adequately from it? Then I can take responsibility for my community, but I don’t relieve the pressure from the causations by taking them on myself as if I can change that.’

As the population with the majority of numbers, privilege and a far greater share of wealth and power, “this is the result of white people. White people have to fix this. I’m not the one keeping my kids back. I’m not the one sending myself to prison. I’m not the one not treating myself for heart attacks. I have a different kind of perspective. I wish I could take a progressive perspective that it’s going to be better some day.”

“But my forever right now is this is how it is and have we defended ourselves, have I done enough to get my community to the next stage, next year, next place. That’s how I see it. If the pressure needs to let up, then white people can let up.”

And there, Mullen sees some cause for optimism.

”There’s plenty of evidence that says that white people have done that. People ain’t wearing robes anymore, they’re not lynching people. They’re not burning out churches like they used to.”

At the same time, the issues remain real. “On the other hand there’s a lot more folk would do if they saw themselves in the middle than someone else.”

“Coming up in Asheville, my kids have black and white friends. The parents of the white kids were just as appalled and worked just as hard to save the black kids who were in that group as anybody.”

Still, “the interpersonal is one thing, but I’m talking institutions, and that’s where the accountability is just not happening.”

—

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by its readers. If you like our work, donate directly to us on Patreon. Questions? Comments? Email us.