As Asheville struggles with low wages and bad working conditions, thoughts on what might have to change for it become a union city

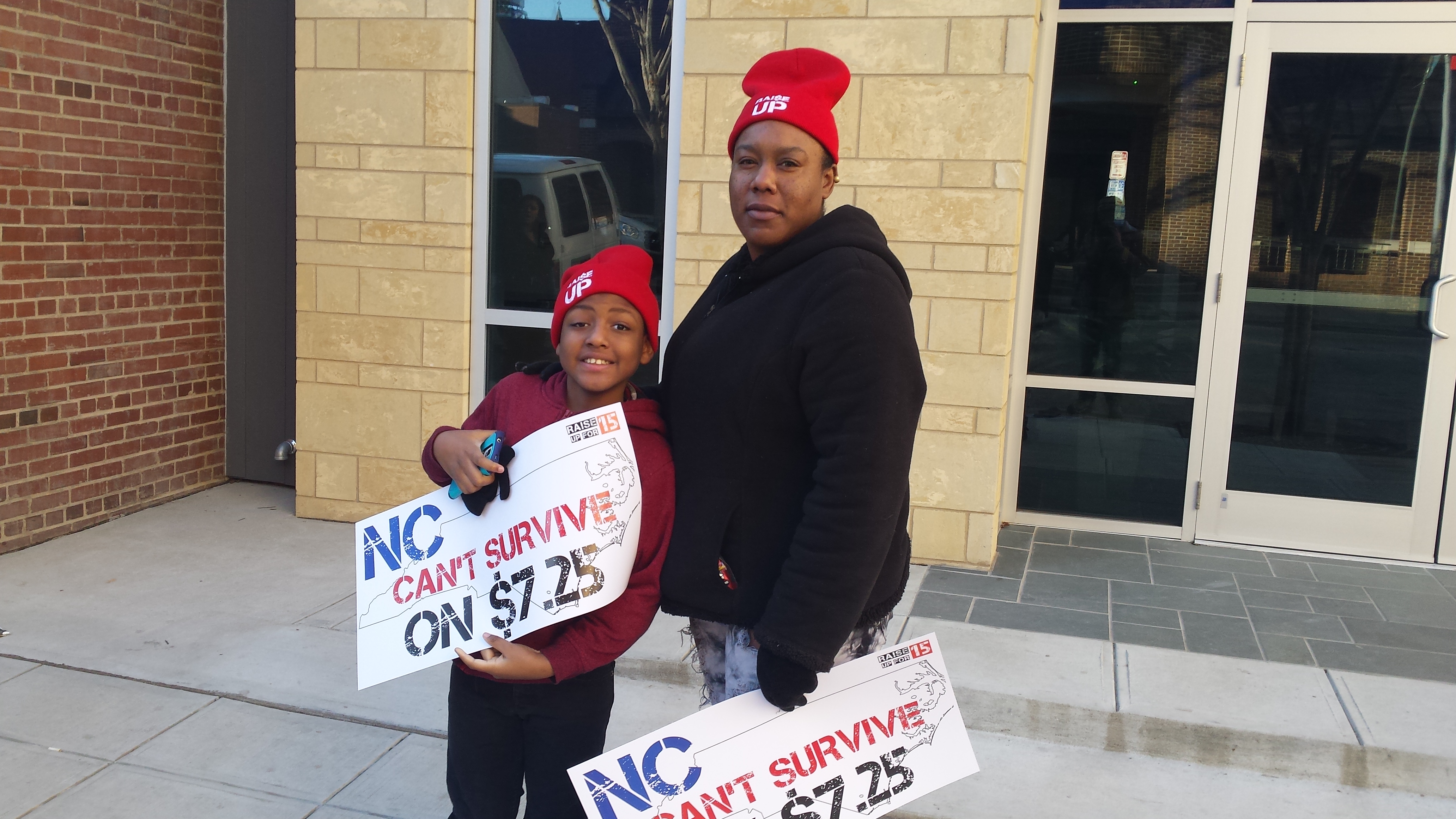

Above: Johaunna Cromer and her son Tejuan at the recent HKonJ march in Raleigh. Cromer, a local fast-food worker, has joined with the labor advocacy group Raise Up for 15 to push for higher wages. Photo courtesy of Raise Up for 15

Asheville is a city with low wages, even by North Carolina standards. In the past decade, wages in the city and surrounding county have actually gone down. It’s also a city with a high cost of living and at the core of its economy are industries — like food service — known to be particularly bad for wage theft, among other problems. In fact, pay here is so low that if Wal-Mart follows through with its just-announced pay raises, starting workers there will make more than the average pay for Asheville’s waiters and bartenders (including tips).

Asheville is also a left-leaning city: Republicans here make up a small percentage of the population and the spectrum in city politics tends to start at moderate Democrat and go left from there.

It’s also a city smack dab in the middle of one of the least-unionized regions in the least-unionized state in the country and unions are rare here.

In my latest analysis for Ashvegas, I take a look at why this is, at the current efforts to change it and some of the obstacles to a more unionized city.

Contrary to popular myth, unions aren’t illegal in North Carolina. Nor is criticizing your employer, talking about how much you make and how you’re treated, among many other rights. In fact, many of those activities are protected by federal law.

There are unions in WNC. Asheville’s firefighters, stage hands, UPS drivers, and workers at the French Broad Food Co-op — just to name a few — are union workers. Josh Rhodes, president of the WNC Central Labor Council, believes that “Asheville has a lot of potential” for increased union organization.

In addition, the past six months have seen increased local efforts by labor advocacy organizations, often called alt labor groups. Raise Up for 15, a regional effort to raise workers’ pay to $15 an hour, starting in the fast-food sector, has an organizer living and working here. Some local food service workers also organized the Asheville Sustainable Restaurant Workforce. Next week they’re holding a workshop on wage theft (3 p.m., Feb. 23 at the West Asheville Library).

While alt labor groups don’t have unions’ legal protections, they also don’t have some of the legal limitations unions have; they can picket and demonstrate across whole economic sectors or, for that matter, whole cities. They also sometimes work alongside more traditional unions in pushing for similar goals. A recent labor luncheon, for example, saw local union leaders praise Raise Up for 15’s efforts.

As for why would someone in Asheville get involved in a labor campaign Johaunna Cromer, a worker at a local Hardees who’s joined with Raise Up for 15, put it this way:

“The workload is too much for $7.25; that doesn’t even take care of the cost of living for single parents raising their children,” she asserted about her reasons for joining the effort. If the wages “did go up families can afford food, housing and take care of their children, pay for daycare education, the list goes on.”

Nor are unions entirely without friends in local politics. After that recent luncheon, state Rep. Susan Fisher voiced her support for ending the separate minimum wage for tipped employees, a step that would raise wages for servers, for example, by a significant amount. In her remarks, she credited those workers with playing a major – and underpaid — role in Asheville’s increasingly famous “foodtopia.”

The potential benefits to unions and labor organizing are real, especially in a town like Asheville where, despite a tourism boom, wages are stagnant or declining. Nationally, even once-skeptical writers are acknowledging that unions provide a way to ensure the average worker doesn’t get completely cut out of economic growth. They provide some real protection for an employee’s existing rights, a big support network and the chance to push for more if necessary. Further, they’re protected by federal law and any contract they wrangle with an employer is legally enforceable. As a place with a sympathetic population, widespread dissatisfaction over wages and working conditions and a history of protest, Asheville has a lot of pluses in the “potential union city” category.

It’s not unprecedented, either. Plenty of workers at tourism destinations like Las Vegas and Hawaii are unionized and the sky hasn’t fallen. In fact, unlike some traditional manufacturing, businesses in places like Asheville can’t up and leave if their workers organize. Helicopters aren’t going to haul the Biltmore Estate to a lower-wage clime if their employees push for a raise. They can’t; place is too essential to their bottom line, and that gives workers here a lot of leverage if they choose to use it. Even major non-tourism employers like Mission Hospitals or Ingles aren’t going anywhere.

There are also some very real obstacles to unions here, and it’s worth acknowledging that reality too. Lower-wage sectors are harder to organize (though not impossible). In addition, because so few workers in Asheville are unionized, there’s not much culture or awareness about unions as a viable possibility. Many people aren’t even aware of the rights they already have under the law, much less that they can press for more without getting immediately fired.

Despite the fact that our economy rests on workers in sectors like retail or food service, for example, the perception is that those workers are expendable. Too often, that’s filtered down to the rank-and-file in those industries as well as their managers. For all its benefits organizing unions can be a difficult, time-consuming process for people who already have little time and are, sometimes, facing a climate of fear at their workplaces.

Also, while Asheville is a very politically active city, it’s also a very fractured one; many people here tend to focus their efforts on a particular cause or non-profit. That makes the kind of broad organizing necessary to put real momentum behind a labor movement sometimes difficult. That’s one reason why the role of alt labor groups here is interesting to watch; they may serve as a bridge between the non-profits and protest efforts Ashevillians are used to working with and more traditional labor organizing.

Full disclosure: I’ve witnessed both the benefits of, and obstacles to, unions here. It’s worth remembering that the Blade emerged out of a union fight, to deal with major issues at local newspaper Mountain Xpress. While I’d always believed that organization and power were necessary for working people to get a fair shake and had covered labor issues before, witnessing that fight up close provided some illuminating lessons.

In our case the Communications Workers of America local president, Curtis Shew, and the CWA’s regional office were incredibly supportive. They fought hard for our rights and thanks to them, one of our colleagues won compensation and a whole parcel of horrible rules for employees were thrown out. To this day I remain thankful for that.

Importantly, it made me realize that without that support, we would have had nothing. We wouldn’t have had a chance even to protect the rights we supposedly had under existing labor law. Rights that, looking back, I’d seen ignored or violated in this city on such an endemic scale that most people weren’t even aware of their existence.

There is power in a union.

So the Blade is unapologetically pro-labor. We believe that the stories and lives of the people that make this city work have value, that they’re too often ignored and that it’s long past time to end that. Loudly.

We believe that the same people deserve less desperation and more power over the course of their lives and city, and we believe in their right to organize to try to make that happen.

We are, as I wrote awhile back, the media outlet less concerned with the new restaurant opening up than how the workers there are treated.

Ethically, as a journalist who more or less said all the above publicly before the Blade started, it would be wrong for me to hide it; so I’m honest about my views and where we come from. As professional media the Blade is also independent of any particular organization or campaign, and will remain so. Our readers fund us directly.

Even among people and groups that are pro-labor there are, of course, debates about how to proceed, which tactics are best and how to attain their common goals. I don’t expect those will cease. The Blade will portray that reality fairly, with all its complexities, to the best of our ability.

So, reader, that’s where we come from.

The Xpress fight also revealed something, as did learning more about some too-often ignored history here: the successful late ’90s fights to organize the French Broad Food Co-op. The upper management of plenty of businesses here, including plenty of locally-owned businesses, don’t really react any differently from their corporate peers when it comes to organized labor or their employees’ demands. They are just as capable of ignoring people’s rights, exploiting their workers and busting unions.

It also points to one of the big shifts — one hard to put into a straightforward analysis — that would have to happen for Asheville to become a union city.

A major part of our city’s mythology (and good lord do we have one) is the wealthy coming here and raining down beneficence upon the population. From the lauding of the Vanderbilts and Grove to the reflexive warnings about never, ever saying anything bad about tourists — even in jest — the impression is that the populace here has to remain super-nice to everyone about everything, regardless of what they’re going through. This pairs nicely with the accompanying myth that those in charge of organizations or institutions here are good people acting in good faith, and any problems are only due to a failure to properly communicate. This is why discussion about resolving issues here perpetually takes a tone of “dialogue” and “stakeholders” rather than conflict and demand.

“Power,” as John Adams put it, “always thinks it has a great soul.”

It’s an illusion, of course, and there are plenty of examples from our city’s history (those of Dickson and Jones, just to start) that teach some very different lessons. But that myth means that Asheville’s big on being nice, at least on the surface, and hence a lot of efforts here have revolved around appealing to positive PR and the better angels of local owners and institutions’ nature. Some of these efforts are plenty laudable and some businesses, to their credit, have responded by improving pay and working conditions.

The rub, as UNCA professor Dwight Mullen said recently, speaking about activism against the injustices facing the local African-American community, is “what will you do if they refuse?”

Throughout history — and in Asheville today — refusal is far, far more common than acknowledgement of the need to change. Goodwill is more fickle than power. Always. If an institution believes it can safely ignore a population hurt by its actions, it probably will.

So, when it comes to the workplace, unions teach the opposite lesson: instead of relying on the chance that the person with the purse strings might do the right thing, they rely on creating a giant problem if they don’t. From the strikes, solidarity and legal challenges of traditional unions to alt labor groups’ walkouts and protests, organized labor marshals power and support outside of an employer’s whims. Instead of “we’ll trust you and hope things turn out well,” it’s “we’re organizing to help each other. If you hurt us, we will make life hell until you stop.”

This approach doesn’t rule out sitting down to talk things out; a main part of unions’ power is called “collective bargaining” for a reason. But it does acknowledge that dialogue only really happens after “ignore the problems we’re creating and tell people to shut up about it” is no longer an option.

However, that route requires valuing justice over being nice. It requires viewing business owners not as magical saviors, but as people capable of evil just as often as good. It requires realizing that friendliness can mask exploitation. It requires a willingness to break organizations, careers and reputations until real change happens.

And that’s something this city’s still wrapping its head around.

Asheville has changed before, and will change again. When looking at our city today remember that there are, always, other alternatives.

—

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by its readers. If you like our work, donate directly to us on Patreon. Questions? Comments? Email us.