[IMPORTANT: additional evidence and research has revealed that the figure identified as Isaac Dickson in this piece was instead Roosevelt bodyguard Frank Tyree. For more on this correction, see here.]

Recently found images of legendary African-American leader Isaac Dickson with Theodore Roosevelt shed new light on an important chapter in Asheville’s history

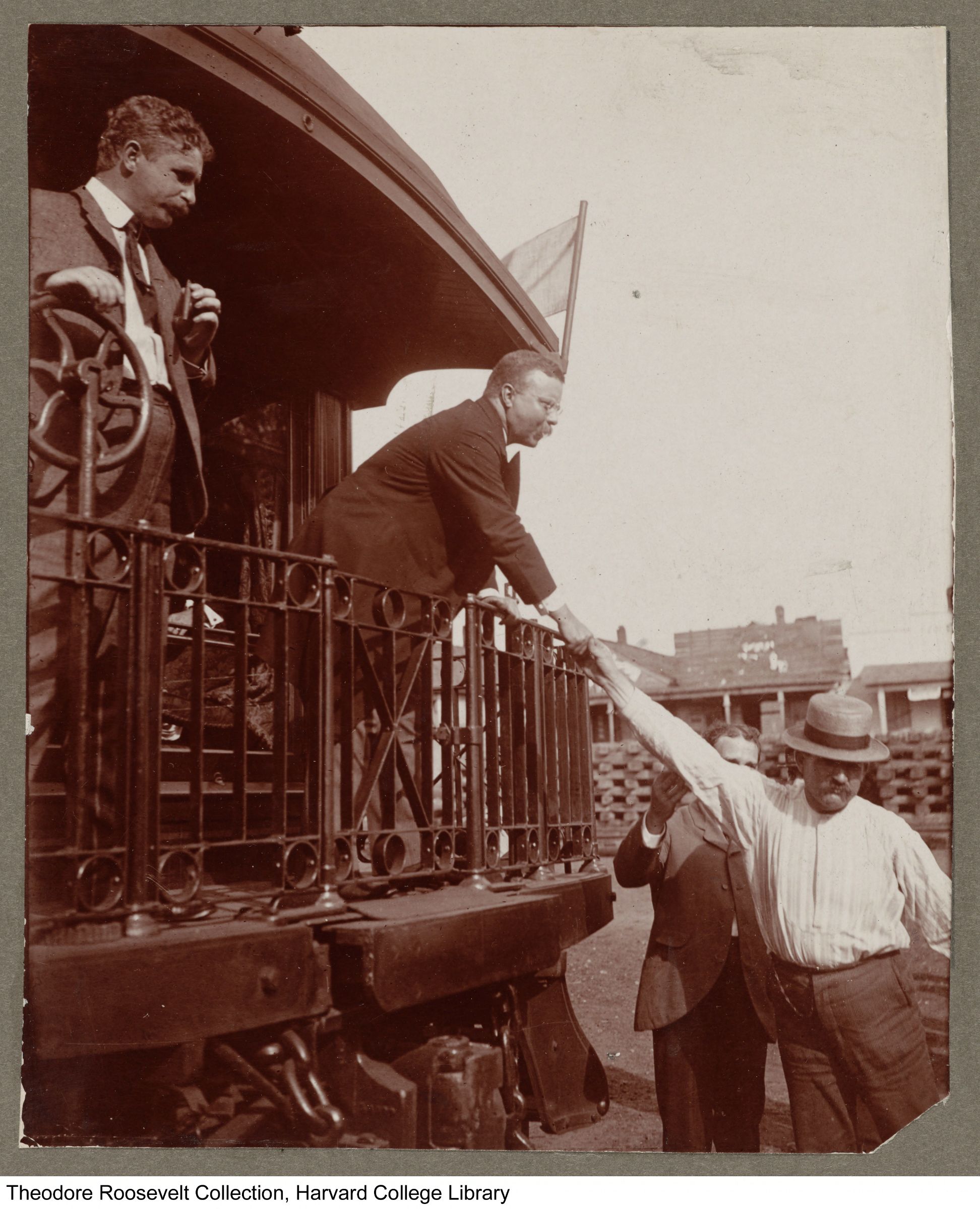

Above: Isaac Dickson, near the center, walking beside President Theodore Roosevelt’s carriage as it left the rail deport during his 1902 visit to Asheville. Theodore Roosevelt Collection, Houghton Library, Harvard University

Last year Jenny Bowen, a local history writer and photographer, was delving into photos of President Theodore Roosevelt’s 1902 visit to Asheville for an upcoming Blade piece on the politics and history behind the event. That search took her to the digital archives of the Theodore Roosevelt Collection, based at Harvard’s Houghton Library.

“I’d seen all these photos of Teddy Roosevelt in Asheville, it was such a grandstand moment in our city’s history and I really wanted to know the story behind it,” Bowen recalls. “Thankfully with the age of the internet, a lot of libraries are starting to digitize their collections, making things easier to find than before.”

There, Bowen saw a photo of an African-American man in a suit, walking alongside Roosevelt’s carriage.

Roosevelt’s welcoming party leaving the depot and heading possibly to the Biltmore Estate to take photos before heading up Main Street to Court Square (now Pack Square) for the speech. The man in the foreground by the President’s side accompanying his carriage and looking down towards the camera is Isaac Dickson. Theodore Roosevelt Collection, Houghton Library, Harvard University

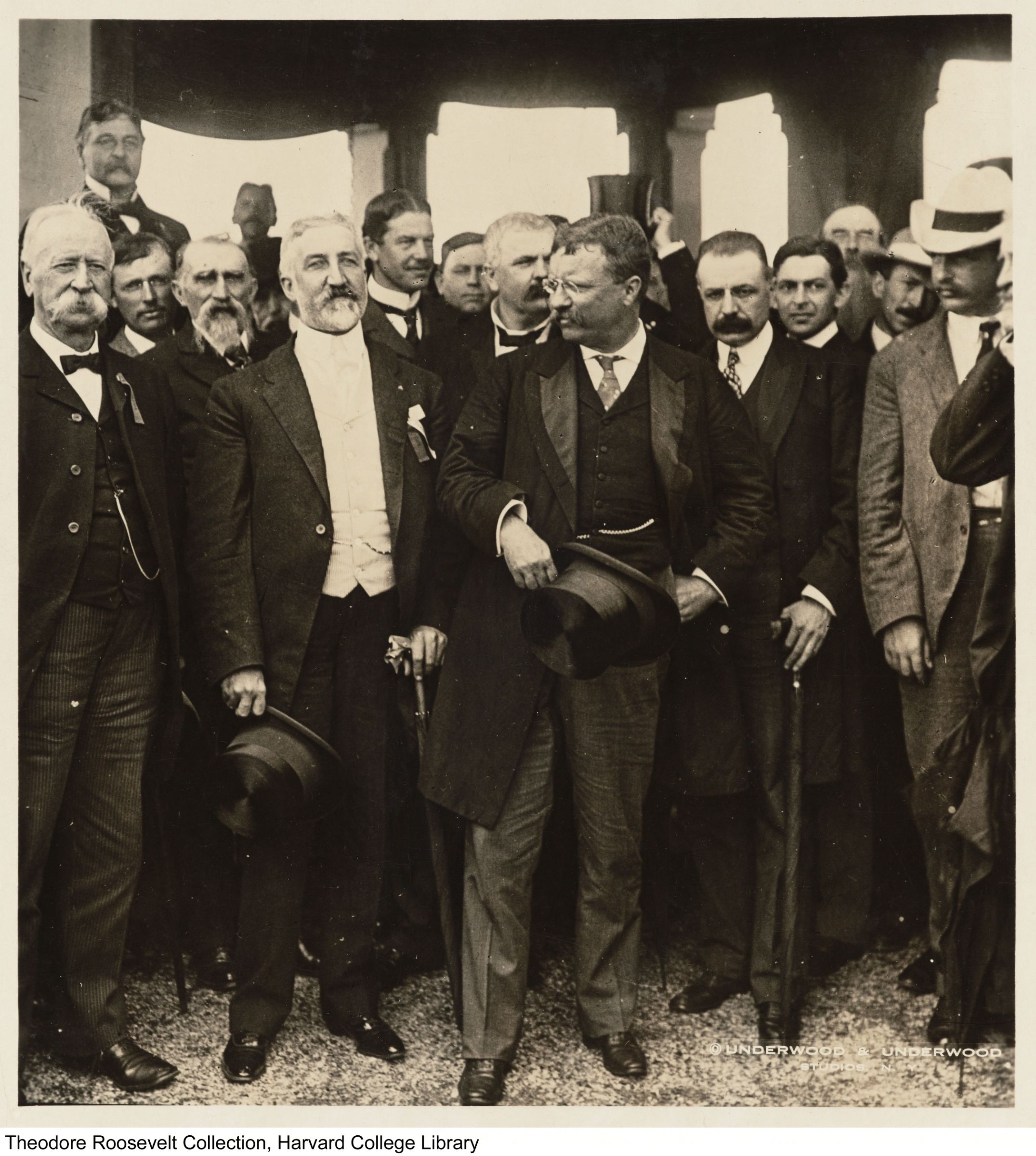

The same man showed up in other photos, with Senator Jeter Pritchard and local dignitaries standing beside the president on his train.

The President’s party, probably at the depot, after arriving in Asheville. Senator Jeter Pritchard stands directly left of the President, Isaac Dickson is at the far right. Theodore Roosevelt Collection, Houghton Library, Harvard University

He also looked familiar, based on her knowledge of the city’s history. She compared it to some other photos she’d looked at for an Asheville History post on local African-American leader Isaac Dickson, and that’s when it struck her.

“I put the years together, the status of who Dickson was at the time and understanding Roosevelt’s history, he had Booker T. Washington in the White House just 11 months prior” to the Asheville visit. “It makes sense that this person standing next to him, but not being a Senator, not being a mayor, walking next to the carriage, it makes sense that it would’ve been Dickson.”

Arriving in the city in the late 1860s, Dickson emerged as an important political, business and civic leader. He played a major role in the founding of Asheville’s school system, the development of the local African-American community (part of downtown was known as “Dicksontown”) and the founding of civic institutions like the YMI.

At first, Bowen only found a few photos, and while she believed the person in question was Dickson, verification remained uncertain, But after looking at additional photos and finding more images of Roosevelt’s visit in the Harvard archives, his identity became increasingly clear.

The President. possibly at George Vanderbilt’s Biltmore Estate, being photographed with the welcoming party and local officials before his speech. Senator Jeter Pritchard can be seen to the left of the President, and Isaac Dickson is in the white hat at the extreme right of the photo. Theodore Roosevelt Collection, Houghton Library, Harvard University

UNCA professor Darin Waters, an expert on the history of African-Americans in Asheville, especially in the period after the Civil War, examined the photos at the Blade‘s request.

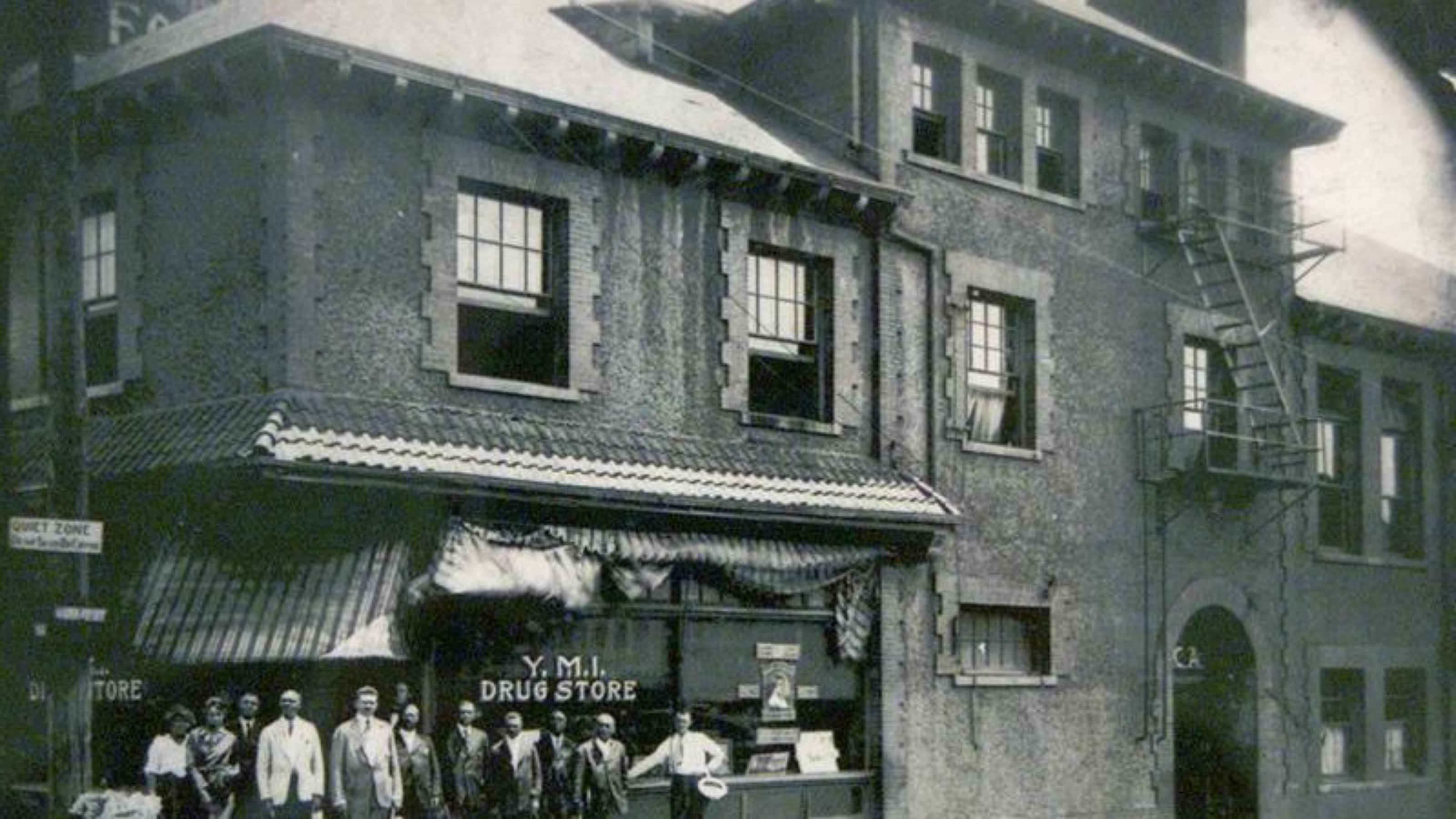

“Based on earlier photos of Dickson, we know that he was a fair-skinned man and based on other photos of him, especially the photos with other civic leaders in front of the YMI it appears to be the same person,” he tells the Blade. “There’s also the fact that he would be someone in that type of a position when Roosevelt came to Asheville makes sense. Roosevelt maintained a relationship with certain black political leaders and did appoint a number of black leaders to different federal positions when he was President. Not just in the North, he was doing this in the South as well.”

While he was a major civic leader, there are only a few known photos of Dickson. But those that do exist, Waters notes, led him to believe that these images were of the local leader.

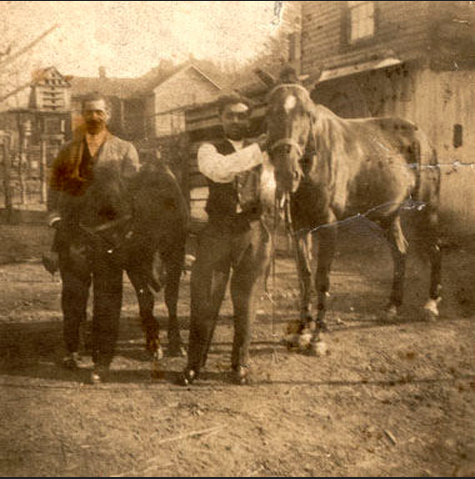

Isaac Dickson with his nephew, James Wilson, in front of his home at 133 Valley Street, late 1800s. Heritage of Black Highlanders Collection, UNC-Asheville Ramsey Library

Local leaders in front of the YMI, circa 1905. Dickson was a co-founder and original treasurer for the YMI, and a man matching his appearance in the Roosevelt photos is in the center of the group. Heritage of Black Highlanders Collection, UNC-Asheville Ramsey Library

Gene Hyde, UNCA’s archivist and head of its special collections, home to many of the known photos of Dickson, notes that”Waters is the leading scholar on black Asheville in the 19th and early 20th century.”

Due to the fact that the digitization is increasing the amount of archival photos publicly available, “it makes sense that no one from our local historical community had found these photos before,” Bowen notes and Harvard’s archivists wouldn’t have had the local knowledge to identify Dickson. “Almost all of these photos were taken by a photographer traveling with Roosevelt and then they went into the Harvard collection.” She’s assembled these photos and others of Dickson into a single archive.

Dickson’s importance is key to understanding Asheville in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Waters notes, an era that laid the groundwork for the city we see today.

“He was the leading African-American businessman and, to a degree, the leading political leader for African-Americans in Asheville and, I would say, probably most of Western North Carolina,” Waters tells the Blade. “That gave him a higher position of authority, especially among African-Americans, and respectability among the white population as well.”

Dickson first shows up as a major figure in Asheville’s political history in 1888, when he was elected a member of the first Asheville City School Board, the first black person to occupy such a position in the state. Though Waters believes his year-long tenure was largely part of a “political tradeoff,” the events of that year also demonstrated his political clout. The previous three times a vote to fund local public schools was put on the ballot, it had failed.

“It says a lot about his leadership within the African-American community,” Waters says. “What he gives the city in 1888 with the creation of that school board is he’s able to deliver the African-American vote. That’s clear when you look at the numbers.”

With Dickson’s leadership, the measure to establish the school board won by a razor-thin margin, Waters notes, “and it’s really that African-American vote that pushes it over the top.”

Given that, he adds that it makes sense Dickson would be with Roosevelt’s party, as “he was well-respected by the white community here as someone who could speak for the African-American population.’

Roosevelt’s visit came against a backdrop of a rapidly-changing country and city, and much of it not for the better. Just four years before, a coup d’etat by white supremacists in Wilmington overthrew the elected biracial government, rampaged through black neighborhoods and forced thousands of citizens from their homes. New laws also stripped away rights won in the Reconstruction period.

But Roosevelt, while he had his own share of racist views, still viewed African-Americans as a part of the Republican coalition, especially in the South. Waters notes that the inclusion of some African-Americans in federal positions wouldn’t cease until Woodrow Wilson became President a decade later.

Indeed a newspaper article later that year, preserved in the Roosevelt Collection, notes the President’s differences from North Carolina Senator Jeter Pritchard, a member of his own party, declaring that “The Chief Executive thinks Senator Pritchard went too far in excluding qualified negro voters from the State Convention.”

Asheville was also changing economically, and given the upheaval elsewhere, its leaders were keen to present a different image.

“This is a time when Asheville’s tourism industry is booming. By the time [Roosevelt] comes here, Vanderbilt is already living here. It’s a tourist mecca for the South,” Waters says. “The community wanted to present as good an image of itself as it possibly could. Showing that you had a respectable African-American community was important to Asheville’s image.”

So at the time “here in Asheville, at least, it’s generally peaceful,” Waters says. “Certain African-Americans have been disenfranchised from the political process, but someone like Dickson would have been able to continue to probably be an active voter because he had the money and he was educated enough he would have been able to pass any type of literacy test.”

“Asheville is different in this regard,” he says. “It’s trying to build an image of a more peaceful, tranquil African-American community, but clearly it’s this kind of the veneer that’s created.”

Despite the harsher reality under that image, Waters notes that in 1902 Dickson would still have exercised considerable sway as “someone who had the ear and pulse of the black community.”

Isaac Dickson smoking a cigar on the caboose of Roosevelt’s train while President Roosevelt shakes hands. Which location on the President’s train tour throughout WNC this photo takes place in is unknown. Theodore Roosevelt Collection, Houghton Library, Harvard University

In these circumstances, “politically, [Dickson] would have been able to maneuver some” to try and improve conditions for Asheville’s black community. But harder times were coming, as the racial climate was about to drastically worsen with the 1906 Atlanta race riot and, shortly after, the Will Harris shooting in Asheville. Following that, Waters says, a more “hardcore racial segregation in every facet of life” would take hold.

The photos, he notes, serve as a reminder that at the time of Roosevelt’s visit, “the Republican party itself was still kind of committed to the idea of political suffrage for African-Americans to some degree. I think it illustrates that. People who had achieved a certain standing in their community were still seen in the Republican Party as being respectable members of the party.”

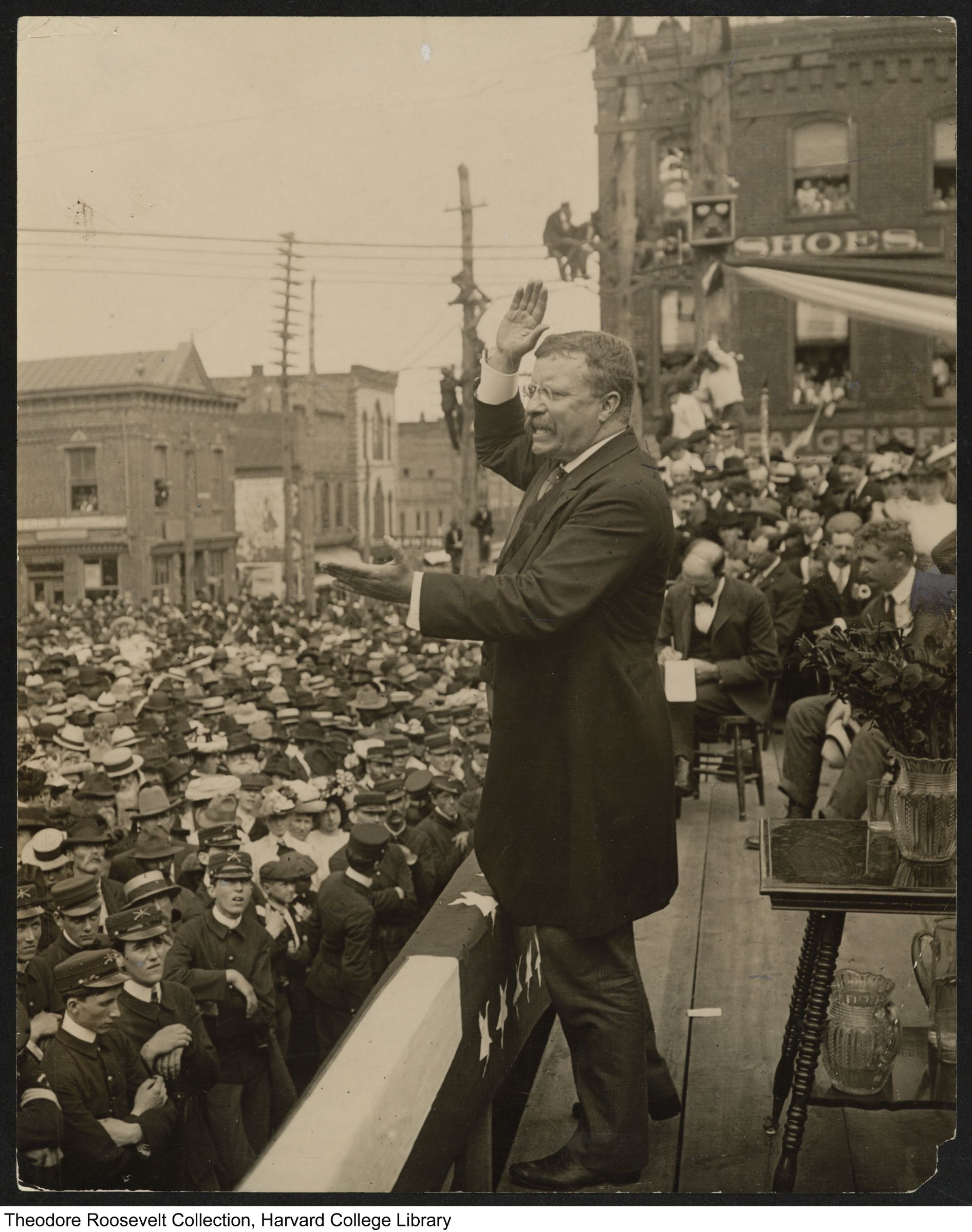

The President speaking to a crowd in downtown Asheville that some reports estimated at 10,000. Isaac Dickson is sitting down and leaning out behind the President, as seen in the right part of the image. Theodore Roosevelt Collection, Houghton Library, Harvard University

“It is an interesting story,” Bowen says, as Dickson navigated a changing city and Roosevelt a changing America. “There was a backlash when he had Washington at the White House. So having Roosevelt smoking cigars with Isaac Dickson, it’s an important moment in Asheville’s history.”

“If it was Woodrow Wilson, this wouldn’t have happened,” she adds. “It’s important to Roosevelt’s history and Asheville history to remember this moment.”

The scene, she believes, also illustrates a paradox at the heart of Asheville: “we have always been a progressive city, trying to be on the cutting edge,” but one that also has a long and often unaddressed history of segregation, as “African-American history in our city is still grossly under-represented and misunderstood.”

Bowen said that for her, the photos helped reveal a new and important dimension to the story of Roosevelt’s visit, as it collided with Dickson’s Asheville in ways that are still relevant today.

“Dickson was a man who helped lead people. Unfortunately, that also ran into a very hard backlash,” one that would only increase with the effects of redlining and segregation as the 20th century continued. “We need to learn more about that past so we can start fixing that scar.”

“The past creates the present, which sets the tone for the future,” she adds. “Even though it was over a hundred years ago, it’s still relevant.”

“It shines a spotlight on what race relations were like,” Waters says of the photos’ importance. “This gives some evidence that prior to 1906, things were still relatively fluid.”

—

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by its readers. If you like our work, donate directly to us on Patreon. Questions? Comments? Email us.