Over its two-day retreat, Asheville City Council set some goals, split on affordable housing, clashed with staff and set the stage for some interesting times ahead

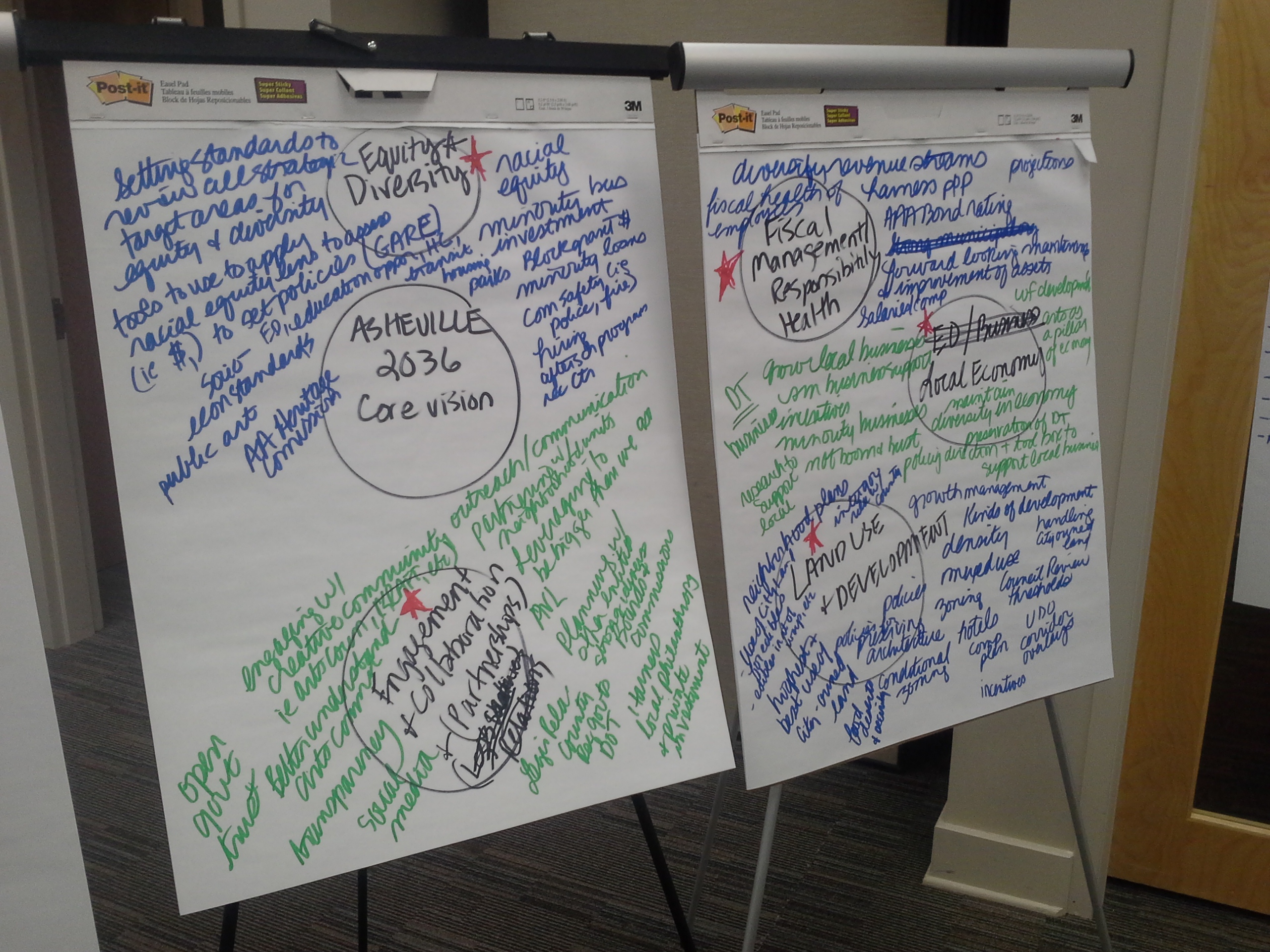

Above: the goals of Council members and staff during part of their annual retreat

Every year, Asheville City Council has a retreat. Despite the name, they don’t (usually) take off to some secluded spot for trust-building exercises and s’mores. But they do gather with senior staff, usually somewhere downtown, and plot out their goals for the coming year.

This year’s retreat — in the last days of January — was longer than usual, taking up two full working days instead of the usual one to one-and-a-half. But then Asheville City Council’s got more on its plate this year, and post last year’s election day upsets, a number of topics — like curbs on hotels, de facto segregation and infrastructure — are getting another look. The retreat even happened as one member, Gordon Smith, is running for a seat on the Buncombe County Board of Commissioners.

While open to the public, retreats only usually attract the attention of a smattering of activists, non-profit chiefs, agency leaders and business types. Admittedly, they aren’t the easiest thing for members of the public who aren’t urban policy masochists to follow. Council members might spend a considerable amount of time debating whether they’re using the word “innovative” too much in laying out their goals amid a pile of general commitments, a torrent of vague language and mounds of cityspeak.

But in the middle of all that, someone will drop that they should end the Bele Chere festival, or that it might be a good time to overhaul the city’s development rules, and the rest of Council will agree, and a major decision will have been made or, at the very least, a different direction set.

What’s more, because of the relatively open nature of the discussions, retreats play a big role in setting priority areas for the city’s budget — arguably the most important vote of any year — and where local government will and won’t focus money.

So out of all that, what emerged this year? If you want a more blow-by-blow account, check out the collection of our live coverage of all two days of the retreat. Here’s some analysis of the major issues that emerged from all that discussion.

Council’s going to fight (with each other) over a key affordable housing measure — As the half of the city that pays rent has no doubt noticed, Asheville’s in the middle of a housing crisis. Even the city’s own officials have acknowledged that their current measure aren’t cutting it. On top of that, a good portion of last year was spent in a knock-down, drag-out fight over short-term rentals (mostly from Airbnb and similar sites). The concern that landlords renting out whole homes to tourists were pouring fuel on an already dumpster fire-level housing shortage was a major criticism lobbed by advocates of curbing the practice through stricter regulation.

But there’s one measure that the city’s so far balked at, one that’s on the books in three other North Carolina cities: inclusionary zoning.

That’s a somewhat jargon-y term for a local law that would require developers to build affordable housing. Inclusionary zoning would compel any developer building a new project to set aside a certain number of units at affordable rental rate — and keep them there — or instead pay an amount to city funds so local government can build affordable units elsewhere. Chapel Hill, Davidson and Carrboro already have this measure, in some form, as part of their local laws.

Last year, it seemed like this measure was gaining traction. A number of Council members and candidates endorsed it during the campaigns and leaders of non-profit Just Economics noted it was a priority for them going forward. At the retreat, Council member Cecil Bothwell said it was time to move on inclusionary zoning, and Smith backed this, noting that the city had studied the issue extensively.

However, while three other North Carolina cities have the measure on the books (Chapel Hill’s has been in place for five years), Manheimer claimed Asheville would get a lawsuit or legislative challenges (a failed state bill last year sought to strip cities of almost any authority to regulate housing at all) and preferred to see the city stick to its current course of voluntary incentives for developers to build more affordable housing.

While it’s unclear if an inclusionary zoning ordinance would get the four votes required, the retreat revealed a Council deeply split over requiring developers to build affordable housing, debates that are likely to grow as the city’s housing situation worsens and the last election demonstrated that established Council members will have to fight a lot harder for their seats.

Expect parks and rec to be a big focus — This year, the city laying out its strategic goals took of projecting what their ideal Asheville will look like 20 years from now. That process didn’t end up being nearly as science-fictional as it sounds. There were no flying cars or Thunderdome arenas, and a reference put in by Council member Cecil Bothwell to fleets of driverless cars in the future city was struck (Smith was more skeptical about that particular feature of a future Asheville).

Much of the Council members’ visions (or “desired future state” as their process put it) basically assumed that, two decades on, all the plans and approaches they’ve been using worked wonders.

However, in the process of those discussions, some more immediate issues and plans did come up.

A major focus centered around Parks and Recreation, responsible for everything from events to community centers and, well, parks. Manheimer asserted that the department was hit particularly hard during the recession and that it was now worth taking another look at increasing city funding. Council member Keith Young also pushed for this to become a priority, noting that these cuts fell particularly hard upon minority communities. Manheimer agreed.

In some specific cases, communities have pushed the city hard on improving the services and facilities it offers. The Southside Advisory Board and community members notably made renovation of the historic Walton Street complex a major issue during last year’s elections, and have kept pressing since. Indeed, just two days after the retreat, Young and Parks and Rec Director Roderick Simmons showed up to a meeting called by the advisory board to assure residents they were looking into improving the facility and had no plans to close it.

Interestingly, this isn’t the only thing brewing on the parks and rec front. Early in Council’s deliberations, Cathy Ball, who oversees the city’s development and transportation operations, advocated starting from scratch and assessing where the city needed to provide parks and recreation services. Later on, Manheimer noted that it was important to take a closer look at Parks and Rec, “what it does and what it costs,” and Assistant City Manager Paul Fetherston echoed Ball’s earlier call, asserting the city needed to decide what the role of the department is.

If that reassessment resulted in major change — say in closing some centers, opening others or selling off land — expect major controversy over which neighborhoods are served and which are left out.

Bond referendums, business incentives and more — A few other specific proposal also emerged as Council discussed its future.

One focus was revenue. During a general brainstorming session on the first day of the retreat, Young noted that to build the “utopia” Council members were laying out in their various plans for the future, the city would need to find additional sources of revenue. In particular, Young noted he was open to a bond referendum.

Council revisited the need to broaden the revenue several times. Council member Julie Mayfield proposed using a hike the vehicle fee to help fund the transit system, the subject of a major ongoing debate, including a push for evening service.

Smith broached using $1 million of the city’s $100 million investment portfolio to help set up Buncombe Community Capital in partnership with Self-Help Credit Union and (he hoped) Buncombe County in an effort to provide funds for local and minority-owned businesses.

None of these met significant opposition from other Council members, and may well show up in the city’s budget as it takes shape over the coming months.

Importantly, the bond referendum idea also stuck, and Council eventually reached a consensus on assessing it. This marks an interesting and important change. As Asheville saw major growth over the last two decades, its aging infrastructure was increasingly taxed, both by tourists and the growing number of locals, while city revenue hadn’t kept up fast enough to deal with the issue.

But while a bond referendum was broached over the years, by 2014 Manheimer was declaring it off the table in favor of moving forward with partnerships (with, for example, federal grants) in areas like the River Arts District that Council viewed as having the potential for a downtown-style economic boom.

But in the ensuing time, the city’s credit rating went up a notch and the last election showed a dissatisfied electorate, so it seems Council’s now more receptive than before. If Council can agree on what form the bond referendum will take, allocate where the resources will be directed and muster public support will, however, remain a major question.

City government declared racial equity a major focus — Council decided to make racial equity a major focus in their future plans, something brought up by Young, backed by Smith and acceded to by all of Council.

De facto segregation remains a major issue in Asheville, as racist policies like redlining hit particularly hard here, with impacts that still remain today. On a number of fronts, from health to education to minority-owned businesses, inequity continues. In some areas, like minority-owned businesses, Asheville lags badly behind state averages as well.

The past few years, however, have seen increased organizing from the local African-American community on a range of issues, with ensuing discussion and public demonstrations. There was also increased African-American voter turnout in the last election, which saw Young’s win end two years of an all-white Council.

Notably, the goal doesn’t just generally commit the city to pursuing racial equity. After Young expressed doubts about progress being made toward real racial equity without specific ways to measure and hold the city accountable, discussion turned towards using tools and standards developed by the Government Alliance on Racial Equity. Smith noted he’d seen GARE’s work featured at a recent government conference. Diversifying the city’s 44 boards and commissions, which often play a key role in crafting policy in the early stages, was also mentioned as a priority.

Notably, GARE’s standards don’t just measure equity within city government, but also in how city government deals with matters like contracting or allocating resources to neighborhoods. When those criteria are applied to Asheville, it will be interesting to see what insights they produce.

The era of good feelings between senior staff and Council may be over — Under a Council-manager system, the appointed City Manager has a huge amount of power, as they oversee the day-to-day operations of the vast majority of city employees and are in charge of implementing almost every city policy. The average city manager, in most cities, only lasts about four to five years. However, City Manager Gary Jackson has remained in his seat for over a decade.

In any city, the professional staff form their own blocs and power centers, with agendas, interests and ideas about what government should and shouldn’t advance. Asheville is no exception.

Senior staff and Council in Asheville are usually close allies, as evidenced by Jackson’s long tenure. It’s not just that: Council has actively supported the manager through some major upheavals. Even when considerable problems – like years of issues at the police department under multiple chiefs — have arisen, Council’s usually voiced confidence rather than criticism in the top officials that oversee the city bureaucracy. At one Council meeting last year, things were cozy enough that officials even presented Jackson, an avid cyclist, with a large picture of him winning an award at a recent bike race.

Even on the rare occasions disagreements have surfaced — like Jackson and senior staff’s unsuccessful attempt to curb an effort to give all city workers a living wage last year — Council’s usually avoided direct criticism.

But the retreat saw some criticism of Jackson and senior staff, for once, emerge, and some different assertions about the balance of power between elected officials, citizens, and appointed bureaucrats.

To begin with, Council brought in a facilitator from outside to handle the retreat. While this isn’t unusual, this year’s facilitator, A. Tyler St. Clair (chosen by Jackson and Manheimer), at multiple points espoused a very definite philosophy of how the city’s local government should run. St. Clair is currently with the University of Virginia following a 15-year stint as an administrator in Virginia’s prison system and an eight-year run with the local government of Lynchburg, Va.

Usually the facilitator will try to follow a general agenda and might suggest some language for a specific goal or try to resolve a communication impasse. But St. Clair went a step further: she began the retreat by cautioning Council members against getting involved with the goings-on of individual city departments and also warned that divided votes “hurt productivity” and relations with city staff.

From covering multiple years of retreats, I can say that St. Clair’s warnings were unusual, and are particularly interesting coming at a time when the last election saw upsets by candidates who disagreed with Council’s current majority on a number of issues.

St. Clair later directed Council not to put forward any item for the city’s goals that didn’t have consensus among the group.

This was actually commented upon by Smith, who disagreed with St. Clair and countered that Council was not a consensus-driven body — by its nature, its members would disagree and some issues would come down to divided votes — only for St. Clair to reassert that Council only needed to make issues it could come to a consensus on a priority during the retreat. Notably, despite these disagreements, Smith still joined the rest of Council in effusively praising St. Clair’s facilitation at the end of the retreat.

While not a direct criticism of or by Council, Jackson also notably expressed concerns about the balance of power with the boards and commissions. Council appoints members to 44 boards that oversee various areas of city policy. Some of these, like the Planning and Zoning Commission, have considerable power in their own right, and they can often play a key role in crafting future policy, even if Council later modifies their proposals.

But Jackson complained that the boards were too independent and he felt, didn’t listen to staff sufficiently, to the point where he believed they needed “education” on their role.

“We have too many places where things start up where they shouldn’t start up,” Jackson said.

Perhaps the most substantive disagreement, however, came in the latter part of the retreat, when multiple Council members offered concern and criticism on the Food Action Plan. Council passed the plan four years ago, in an attempt to use the city’s resources to encourage more local food production and less food deserts. But now, most of Council perceived little action taken by city staff to actually put the plan into effect.

This came not just from a single Council member. Wisler started off, noting she felt “some frustration” over what she saw as a lack of progress and staff motivation on the matter. Jackson quickly objected, claiming he wanted to “inject some reality,” contending that staff was taking the issue bit by bit and that the public needed to give them the benefit of the doubt and remain patient.

But Young, Smith and Bothwell all voiced similar concerns to Wisler’s, even at some points outright disagreeing with Jackson’s assessment and noting a level of frustration from the public. Leaders on the Food Policy Council, which helped craft the plan, have sharply criticized city staff, claiming they’ve straight-out ignored many of the plan’s provisions.

Also, despite Jackson’s reassurances, during the discussion City Attorney Robin Currin noted that many of the plan’s provisions haven’t been through legal review, which is typically a key step to the city actually putting something into practice. At the end of the discussion, Jackson said he’d be back with more information within 90 days, and that seemed to mollify Council.

The food policy issues raises a larger dilemma over the balance of power within the city, and it’s probably the most important question from the entire retreat: if Council, as the city’s elected leaders, pass a measure, and city staff simply don’t carry it out, what happens?

—

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by its readers. If you like what we do, donate directly to us on Patreon or make a one-time gift to support our work. Questions? Comments? Email us.