The Lee Walker Heights overhaul is one of the largest housing deals in Asheville’s history. It just took a major step forward, as the city also cut a deal with Duke. A look at the complicated history of power, poverty and race behind the project

Above: The Lee Walker question, art by Paul Choi

Welcome back, readers. Thank you for your patience. For the past few weeks, we’ve been dealing with some collaborative projects (more soon about those) and some unexpected delays due to life circumstances. Thank you also for your support during what were a pretty tough few weeks. Regular coverage resumes now. — D.F.

In 1950 rows of townhomes went up on a site near Southside Avenue, with only one steep road leading into the new development. It was, importantly, Asheville’s first public housing, named after W.S. Lee, a professor at the famed Stephens-Lee High School and J.W. Walker, a doctor and tuberculosis specialist. It marked the return of the Housing Authority of the City of Asheville — a product of New Deal reform efforts — from World War-induced hibernation, and the beginning of Asheville’s public housing system.

Over the coming decades, that system grew, intertwined with “urban renewal” projects that demolished whole neighborhoods and racist policies like redlining that maintained segregation, especially in housing. HACA also changed during that time due to everything from rent strikes for tenants’ rights to federal laws. Despite its name HACA is not controlled by the local government; it’s an independent agency — though the mayor does appoint its board — that directly receives federal funds, governing a city within a city.

Asheville’s public housing system is now home to over 3,100 people, one of the largest constituencies in the city. Many of its aging developments underfunded and in disrepair as the city continues to grapple with issues of segregation and poverty, in the middle of a very different housing crisis. Over the past two years, a controversial management and funding change raised concerns about evictions, transparency and possible privatization. That change, HACA leaders said, happened as a response to sharply declining federal funds for public housing. That reality, they claimed, necessitated a new approach, and more deals with other entities to deal with their aging developments.

The city’s local government has repeatedly dubbed Asheville’s overall housing situation a crisis, and a worsening one. Just this week, the news once again features headlines that our city has one of the least sustainable housing markets in the nation due to the one-two punch of low, stagnant pay and skyrocketing costs.

Historically, city government’s emphasized deals with local developers, especially non-profits, as a possible way out. Backed by its development powers, incentives, loans from a housing trust fund and ability to dish out some federal housing grants, city leaders have sought to create enough affordable housing to blunt the trend. But while one city-commissioned study found this approach put Asheville’s government in the lead among N.C. cities in creating affordable housing units, the crisis has kept getting worse.

Last year, that all collided as HACA and the city looked for a way to demolish the aging Lee Walker and replace it with mixed-income housing including both public housing rate units and other units at a range of rents. This will be a modern complex, designed according to residents’ wishes, that houses the Lee Walker residents while also increasing the amount of affordable housing in the area — more than doubling the units on site — and making the complex far less isolated from the surrounding neighborhood while adding sidewalks, green space and community facilities.

That’s the pitch at least, though the specifics of the plan have attracted a lot of scrutiny given the history of controversy around public housing and its administration. As the deal, one of the largest the city’s ever been involved in, brought together three organizations — Asheville’s government, the housing authority and a major local non-profit — and the fate and wishes of over 90 families, there’s a lot to navigate.

But, as much was at stake, that’s not the only deal involved. Next to Lee Walker Heights is a piece of property owned by power giant Duke Energy. Obtaining access to this property could allow for considerably more units as well as a key access road. But the city is also in the middle of a back-and-forth with Duke over controversial substation proposals late last year, and the corporation attached some strings to that deal too.

On April 26, the deals all came before Asheville City Council for approval, and as with any set of complicated negotiations, there were important things underneath the surface one needed to know.

Shifting times and old questions

In 2014, HACA embarked on a major shift called Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD), that involved shifting funding streams for almost all of its units to a different pot of federal money. HACA leaders touted this as a necessary change to halt the bleeding caused by repeated federal cuts to the usual sources of money — in 2013 it saw $1 million cut and had to lay off 20 percent of its staff. That reality was “the blunt force” the whole system was facing, as HACA COO David Nash put it.

But RAD was controversial around the country, because shifting from the old funding sources also meant shifting away from programs, protections and restrictions associated with them, some of which were put in place by tenant demand over the decades. Public housing residents and activists feared that RAD could open the door for privatization, a fear compounded by the history of public housing and “urban renewal” in the city and the fact that the land Asheville’s public housing developments sit on has become increasingly valuable over the years, due to some of the same forces that drove skyrocketing housing costs across the city.

At multiple meetings, residents and activists raised these concerns, calling for more transparency and more resident control over the process, especially given a history of skepticism.

“This feels a lot like urban renewal,” Olufemi Lewis, a Hillcrest resident and activist, noted when RAD was up for consideration.

Around the same time, an investigation by Carolina Public Press showed that there had been unexplained spikes in evictions over the past few years, many for “lease violations” a broad category that can include . While some residents did speak up about these issues, others claimed that they feared for their ability to stay housed if they went against HACA.

One reason for the shift to RAD was to stabilize the system’s funding so that the aging complexes could be overhauled. While both tenants and HACA officials acknowledged the need for better buildings and conditions , the devil was once again in the details: what would happen to the people displaced?

More than the nearly 100 households directly affected is at stake too. If it’s perceived as successful, the same could follow for the system’s major developments like Pisgah View and Hillcrest, affecting thousands over the coming years. While Mayor Esther Manheimer made the city’s commitment to the Lee Walker overhaul and the new affordable units it would bring a major goal — aimed at starting to remedy problems with concentrated poverty and segregation — others, including candidates in last year’s municipal election expressed some wariness about the matter and a commitment to keep an eye on exactly how the process unfolded.

Meanwhile, the overhaul plans moved forward. HACA partnered with Mountain Housing Opportunities (whose representatives have repeatedly not returned calls from the Blade to talk about the details of the project), a non-profit with extensive experience building affordable housing throughout the area.

HACA hired former Mayor Terry Bellamy to head up an increased effort at community engagement, claiming its biggest outreach effort yet in planning the overhaul. HACA’s own leaders have said that they tried to take more public input than they had for RAD and other previous changes.

By January, plans started to emerge for a development that would include about 120 units of varying affordability alongside 96 dedicated to the public housing residents.

In this case, a committee of Lee Walker residents did meet repeatedly to plan with HACA, the designers of the new project. The residents on that committee have spoken highly of the process, saying it was more open than before and that they feel the changes are for the best.

But others were not so enthusiastic, especially as the process for Lee Walker moved forward. In January, a petition gathered 133 signatures calling for Council to approve no money for the overhaul until several reforms were carried out.

DeLores Venable, who started the petition, has asserted that while she’s not opposed to an overhaul of Lee Walker, she also has serious concerns.

“No one’s saying we don’t want better housing in Lee Walker and in the community,” Venable told the Blade earlier this year shortly after the petition started, but its originators “felt there was a better way” and was skeptical given some of the previous controversies.

Their demands went farther than Lee Walker, showing how the issue is intertwined with the rest of the question of Asheville’s public housing. The petition did seek independent audits, assured staff roles for public housing residents in the new development and assurances that existing residents would be able to return. It also sought more assistance for the Residents Council chosen by public housing residents themselves, and a HACA board to be appointed by the whole of Council, not just the mayor, in consultation with the Residents Council.

The matter first came before Council in January for approval of the first part of the multi-tiered deal, a waiver for half the cost of city fees associated with the project, something that would help HACA and MHO secure the state and federal financing necessary to proceed. At the time Nash noted that under federal law any of the current residents have the right to return if they wish it and that while the complex is being demolished, they’ll have the option of housing elsewhere in the public housing system, a voucher to seek homes elsewhere or a possible unit in one of the developments MHO runs.

Some of the residents involved in the planning process also spoke in support of the overhaul, as they would at ensuing meetings as well. However, some Council members also noted skepticism and caution about how many residents would actually return, and said they planned to keep a close eye on the process.

The design for the new buildings in the overhauled Lee Walker Heights, from the master plan by David Baker architects.

The Lee Walker issue returned March 8, when the full plans for the new development were presented before Council, laying out designs for two main buildings and several smaller ones with over 200 units, including 96 for the returning residents (who would be charged 30 percent of their income for rent, an amount that averages to $200), with the rest mixed-income units ranging from $800 to $1500 a month.

“We think this is probably the most transformational project we could possibly do,” HACA CEO Gene Bell claimed at that meeting. “I think we’ve demonstrated that the residents are put first. They have it in writing, you have it from HUD and you have it from me that they will come back. It seems to be an issue but it’s not an issue.”

Instead of the one narrow road leading into the complex, it would now be connected to Biltmore and Southside directly, with wider roads and more pedestrian and green space. Units would be in two main buildings (with several more possibly added if the deal for the neighboring site owned by Duke Energy goes through), with other, smaller ones scattered throughout the site. The developers also wanted to attract more amenities in the space as well, something Lee Walker residents were historically cut off from.

There was nothing for Council to approve that night, but the elected officials’ general opinions on the plan had shifted from somewhat skeptical generally positive, and next time Lee Walker came back before Council, it would require some very definite commitments.

Third time around

By April 26, Council had already talked about the Lee Walker overhaul in their budget deliberations, looking for ways to combine their own incentive funds with loans tied to federal grants to provide the millions necessary for their end of the deal (not counting the possible expansion, costs about $33 million).

Then, on April 26 Council had three parts of the deal (“separate, but interrelated” in the words of Economic Development Director Sam Powers) to vote on. The first part of the deal was a rezoning to allow the overhaul to proceed, the second a deal with Duke Energy and the third a commitment to $4.2 million dollars (which would give HACA and MHO a stronger hand in seeking more funding).

In presenting the rezoning proposal, principal planner Shannon Tuch noted that the 96 units intended for public housing residents would remain that way “for at least 30 years” while the other units would “be affordable to a range of other income levels.”

“The most important thing about this is changing people’s lives,” Bell said. “Our objective when we started this was to give our residents an opportunity to live in modern, updated housing.”

“This has been probably the most inclusive process I’ve ever been involved in the last 25 years of working in housing,” he claimed.

He hailed the deals reached by the city, HACA and MHO.

“This has not been easy going back and forth to find a model that works,” Bell said, adding that he felt that “we all hear a lot of information in the media and it gives us sources that are isolated,” but that HACA had instead sought out views among the Lee Walker residents specifically (earlier in the year Bellamy told the Blade that HACA had not consulted with the Residents Council about the project and that Lee Walker was not represented in that larger group).

“It’s been great,” Crystal Reid, one of the members of the committee of Lee Walker residents, said. “We are the residents who live in Lee Walker Heights, I’ve been a resident since 2009, and it’s been challenging but I’ve learned a lot. [HACA] and [MHO] brought a lot to the plate and I learned a lot.”

“Those outsiders have their opinion and I respect that to the utmost, but I myself live in Lee Walker Heights,” Reid continued. “You will have those that may oppose what is taking place, but I always tell people: with time, change will come, whether we like it or not.”

Sir Charles Gardner, president of the Residents’ Council, questioned where the public housing units would be placed.

“Who determines where these 96 units will be?” he asked, noting that he’d heard from HACA officials earlier that they would be spread out, but was concerned they might be confined to smaller units in a single building.

“Is there going to be any difference between the units for the residents now and the residents that are going to be paying the fair market rate?” he continued.

Nash replied that the federal government required that the 96 units be replaced in the first phase of construction, meaning they would have to be in one of the two main buildings, but they would be scattered throughout on different levels and sizes. After all the buildings are built, he said, HACA will ask HUD to distribute them throughout those built in the second phase as well.

The point, he emphasized, was that HACA would “not reserving some higher-rent units on the top floor, certainly not putting all of the deeply affordable units on the lower floor.”

“What this committee is trying to do is a great success to the residents,” resident Joseph Tarrant said. “We don’t have sidewalks or play area for our kids.”

“Lee Walker is old, it’s the oldest project in the city, and it needs some changes,” he added.

Council quickly moved the rezoning forward.

“President Truman was in charge of the country when this thing was built,” Council member Gordon Smith said. “The world has changed a lot and it’s time we changed with it.”

Rupa Russe, speaking on a later part of the deal, said she was “extraordinarily concerned about the welfare of this vulnerable population” and wanted to make sure that people would not be displaced and that the city should partner with and incentivize more small landlords to help solve the housing crisis.

Nash again reiterated that “we will not just be issuing vouchers and sending them out to find a place in the tight rental market” and would have to assure Lee Walker residents of a unit, probably in one of HACA’s other housing complexes and “have an absolute right to return to the new development.”

As for the $4.2 million, the city would marshall that through a variety of sources, including the city’s reserves, its capital improvement budget, federal grants it oversees. Jeff Staudinger, the city’s head of affordable housing efforts, noted that it was in line with the amount cities generally use to support projects of the Lee Walker overhaul’s size and nature.

It also wasn’t certain, he noted: it committed the city to award the amount if MHO and HACA secured their other tax credits, and would come before Council again for a final sign-off.

Council member Keith Young, while he approved of the deal moving forward, did offer some caution.

“There is a lot of history in Lee Walker Heights,” he said, noting his grandparents were among its first residents. “Any commitment of $4.2 million significantly affects other programs and projects.”

“I think this Council should really, seriously, think about how we address affordable housing going forward,” including using the city’s land and bonds due to how much the scale of the Lee Walker deal would constrain future efforts with the city’s current funding.

Smith asked Council members if any concerns about people’s right to return to Lee Walker had been addressed. Young replied they had, but “my concern going forward is how we look at addressing affordable housing issues after this.”

“I agree,” Smith added. “We’ve got all these different pieces moving forward, but we know they’re not going to be enough, and identifying those resources in whatever form or fashion they need to take, we’re in agreement.”

Mayor Esther Manheimer noted that the city might have some additional funds to direct towards Lee Walker, freeing up a bit more of its other affordable housing funds than originally anticipated.

“For me, this is about addressing the needs of a community that is underserved and providing opportunity for people in our community that have not always had opportunity “The people that live in Lee Walker are participating in their future, they are deciding what their future looks like, and we’re here to help facilitate that.”

She also pointed to the fact that if the city believes it went well, it will “do it again.”

“It’s the oldest public housing project we have in Asheville, and it seems like a very symbolic place to start on a new future for public housing.”

Dealing with Duke

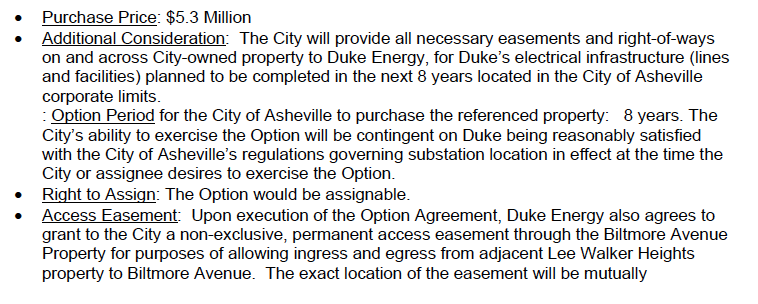

A staff summary of the terms of the deal between the city of Asheville and Duke Energy concerning property neighboring Lee Walker heights.

The remaining part of the multi-tiered deal passed with less fanfare, but it also has far-reaching consequences. It too, tied in issues far beyond just those dealing with Lee Walker. Next to the public housing development is a plot of land owned by Duke Energy, bought by the monopoly for its future expansion, including a possible substation.

Substations have been a bit of a controversial issue recently, due to their potential health effects on nearby people (notably, federal rules prohibit them from being built in close proximity to public housing). Last year, Duke delayed plans for a substation near Isaac Dickson Elementary after a large public backlash about the potential effects. During that, city officials entered negotiations with the company about finding a potential alternate site, possibly on city-owned land.

At the same time, the city needed the property beside Lee Walker, both to build a key road to end the future development’s isolation and to open up land for a potential doubling of the number of units in the new development, So staff, led by Assistant City Manager Cathy Ball brokered a deal with the power giant on that front as well.

“It was considered an opportunity to make a more transformational project,” Assistant City Attorney Janice Ashley said, in presenting it to Council.

The city got some perks: mainly the ability to build a road through it to help with access to Lee Walker, along with the option to purchase the whole site for $5.3 million, which is what Duke paid for it and a bargain in the current super-heated housing market, at any time during the next eight years. The city doesn’t even have to purchase it directly: it could designate an organization like HACA or MHO to do so.

This deal attracted less comment than the other pieces — even the commenters who spoke during the public hearing for this portion. Council passed it unanimously without serious objection.

But the deal gave Duke some major leverage in the ongoing substation controversies. During the debate over the proposed substation near Isaac Dickson, one proposal was for stricter city rules on such facilities. But Duke added a provision against that in this property deal, by the time the city goes to purchase the property, Duke disagrees with any of its rules for substations, the deal for the property is dead on arrival (though the road through it could still be built).

Ball confirmed this part of the deal in a follow-up interview with the Blade after Council gave the go-ahead.

“Duke required they put in that they would be satisfied before we purchase the property,” Ball said. “That does not obligate the city, necessarily, to approve something they would be satisfied with, it would just mean we can’t purchase the property.”

The city also agreed to give Duke any right-of-ways or easements it requests to build power lines across any city-owned property for the next eight years as well, a concession that could turn out to be quite considerable given the amount of city-owned property around the core of the city. However, Ball clarified, this would not allow the building of a substation near Lee Walker or on other city-owned property. “It’s just transmission lines,” Ball clarified.

Meanwhile, the negotiations for another site for Duke’s substation are ongoing. Like the fate of Lee Walker, it will likely be some time before those questions are resolved.

—

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by its readers. If you like what we do, donate directly to us on Patreon or make a one-time gift to support our work. Questions? Comments? Email us.