For city voters, the biggest local question on this year’s ballot are three bonds, the first in almost two decades. A quick look at the issue and what it means

It’s a long ballot this election year, with contests from the presidency to an abundance of state offices, general assembly seats and a majority of seats on the Buncombe County Board of Commissioners all up for a vote.

But Ashevillians have an even longer ballot. For the first time since 1999, city voters will consider taking out $74 million in bonds for affordable housing, transportation infrastructure and parks/rec.

Back in August the Blade had a detailed piece on the issue, how its priorities were set and how it ended up making its way to the ballot back in August and we’ve covered debates and discussions about it as the process continued. But readers have pointed out, rightly, that a primer on this issue is a good idea for voters about to go weigh in on this topic.

What’s a bond and why are we voting on it?

Usually when the city takes out a loan (say to repair a building) it ties repayment to a building or property. However, there’s another type of financing, called a general obligation bond. It allows a local government a lot more flexibility about how it spends that money but commits to paying them back from its property taxes, paid by everyone who owns everything from a house to a car.

Because of that, state law requires city officials to run the bond by a state commission (Asheville’s got the go-ahead this summer) and to submit them to voters for their direct approval.

Historically, Asheville City Councils of varying political persuasions have been averse to bonds. Asheville has a unique history with municipal debt collapsing the city’s finances back in the Great Depression era (one of the crises that led to the creation of the state commission to monitor such bonds), leaving the city to pay the debts off over the ensuing decades. The city did occasionally consider bonds after those debts were retired, with mixed results.

The defeat of an infamous bond proposal to fund the demolition of most of downtown and replace it with a mall is still widely viewed as a key moment that contributed to the area’s revival and averted disaster. The last bond to pass was in 1986 ($17 million for streets and sidewalks, $3 million for an education center. The last proposed bond, in 1999 ($18 million for parks and greenways), failed. As recently as 2014, Mayor Esther Manheimer ruled out a bond as a way to deal with the city’s ongoing infrastructure problems.

But the political climate, at least in City Hall, started to change this year. After an election where voters (and the candidates who won) expressed displeasure with mounting issues like affordability and infrastructure, Council became less reluctant on bonds than they’d previously been, claiming that it might be a way to deal with some of the city’s pressing problems.

Also, last year the city got an upgrade in its bond rating giving it the opportunity to get a better deal. All those factors combined to make the bond more appealing to the city’s leaders than it had been before. Whether a majority of the city’s voters agree remains to be seen.

What would the bond do

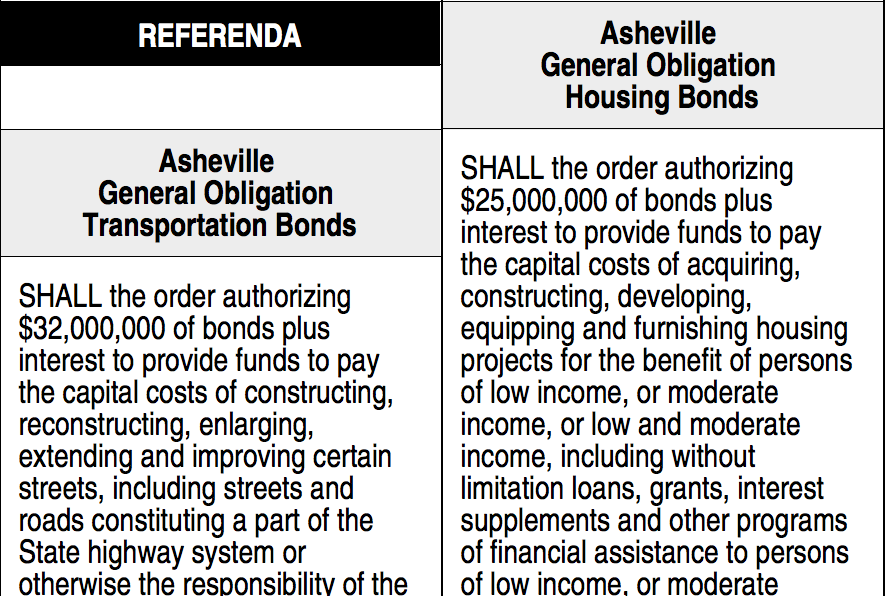

Of the $74 million, $25 million would go to affordable housing, $32 million for transportation infrastructure and $17 for parks and recreation. Voters decide on this questions separately and can vote for all three, oppose all three or support some and oppose others.

Rather than taking the funds all in one lump sum, the city would borrow them as the projects started to come down to the pipeline. If the bonds are passed, they have seven years to start any project that money would back

Right now, the city has a list of proposed projects, and it’s been widely spread around as where the money will go if the bonds pass. However, while there are some legal restrictions on how the money can be spent, those ideas aren’t set in stone. As we’ll get into shortly, where the money specifically goes can still change.

Support and opposition

Bonds can be controversial, usually due to objections over where the money’s going or opposition to the tax increase they can require.

When it comes to municipal politics, opinions on bonds can vary widely. Left-leaning voters can be in favor of them if they see the cash as going to some improvement they favor or dealing with a pressing social problem but opposed (like with the 80s downtown mall) if they see it as a handout to developers or corporate interests. Centrists and center-right types can support bonds if they think they’ll boost business or an economic development deal, but are also wary of tax hikes. Conservatives tend to oppose them, generally being opposed to either the kind of tax hikes bonds often involve or the sizable spending on major public projects they’re directed at.

If the bonds pass, the city will have to raise property taxes to pay them back. However, the exact amount of that increase depends on how a major property revaluation changes locals taxes next year. City officials claim the maximum increase anyone would amount to about $110 a year — or about $9 a month — on a $275,000 home.

In Asheville support has drawn together a number of different political factions, though often for different reasons, as one can see from the variety of organizations supporting the measures. The Asheville area Chamber of Commerce has backed the bonds, hoping they’ll help economic development, Asheville on Bikes supports them they claim the measures will improve multimodal transportation. United Way, Pisgah Legal and Children First/Communities in Schools assert that it will make a dent in the city’s poverty and affordable housing crises, and so on.

A city-commissioned poll indicated strong support for the bond goals, especially for the funds for affordable housing. However, the same poll indicated also indicated a public concerned about the current tax rate.

Organized opposition has mostly — though not entirely — come from the city’s conservatives. At the hearings on the bond referendum, some local conservatives condemned it as a “Ponzi scheme,” claimed taxes were already too high or dismissed the bond priorities as unnecessary luxuries. That opposition has continued in the ensuing months, as detailed in this recent Mountain Xpress piece. A debate in October, for example, saw Mayor Esther Manheimer and former Vice Mayor Marc Hunt — firmly in the centrist camp of the — argue for the bonds opposite former Council member Carl Mumpower and far-right activist Chad Nesbitt speaking in opposition to them.

The public — or politicians — can still change where the money goes

While city leaders aren’t highlighting it, the list of proposed projects they’ve put out aren’t set in stone. Funds just have to go to projects for those general purposes sometime in the next seven years. Most of Council’s up for election next year, and public pressure about a specific project or concern could change much of that list of specific priorities.

Whether that’s a good thing or a bad thing depends, of course, on who you ask. Some critics have portrayed this as proof that the bond funds will be subject to political whims and changing Councils rather than a coherent plan.

Others, however, have seen that as flexibility rather than whimsy: reason to move forward with the bonds to direct funds at some general needs, but then take a close look at where the funds go — and to whom — before changing some of the specific goals.

Back in August, a speaker at one of the Council hearings asserted that, if passed, the city needed to ensure that at least a sizable percentage of the funds go to projects that help the city’s African-American community.

That kind of concern means that if the bonds pass, Ashevillians could then witness another fierce debate: how to use them.

—

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by its readers. If you like what we do, donate directly to us on Patreon or make a one-time gift to support our work. Questions? Comments? Email us.