May Day calls on us, as people and a city, to consider the reality of the world we face and how we can start to change it. Here are three important changes Asheville could do right now

Above: City Hall under renovation. Photo by Bill Rhodes.

“I am, somehow, less interested in the weight and convolutions of Einstein’s brain than in the near certainty that human beings of equal talent have lived and died in cotton fields and sweat shops.” — Stephen Jay Gould

Today is May Day, dedicated to workers around the world and our fight for a better future. While often celebrated more abroad than here, its origins are rooted firmly in America. In early May 1884, an alliance of unions, socialists and anarchists marched in support of widespread strikes in Chicago. After an explosion in Haymarket Sqaure (the cause is still unknown) during a violent police crackdown, some of the leaders were rounded up, railroaded through a sham trial and sentenced to death.

They were fighting for the eight-hour day.

That’s important for a lot of reasons. Many of those marching had goals that stretched far beyond that, views still considered radical now, let alone 133 years ago. They still decided on that immediate step, built an alliance around it and fought. Some lost their lives, not just there but in countless labor fights before and after. But in the wake of Haymarket, historian Nathan Fine would later write, “despite police repression, newspaper incitement to hysteria, and organization of the possessing classes, which followed the throwing of the bomb on May 4, the Chicago wage earners only united their forces and stiffened their resistance.”

It is also important that such a demand was considered so frightening at the time, part of a world envisioned by supposedly dangerous radicals. Rather than acquiescing to that basic demand, almost the whole power structure of the day arrayed against it, bellowing that everything would collapse if people weren’t worked to death non-stop.

Throughout history, it’s always the simple things, like the eight hour day. Let us vote. We need food, housing and decent pay. Healthcare is a right. Bigotry must end. Stop harassing us. We want to live our lives in peace. Bread and roses.

Simple, but never easy.

North Carolina’s multiracial Fusionists were met with bloodshed in the 1890s when they sought local elections, fair pay and basic civil rights. When Emil Seidel was elected the first Socialist mayor of a major American city in 1910 he set to work, over massive opposition, on a system of public parks available to all. The Black Panthers organized free breakfast programs and fought for control of the Oakland Port Authority. The first demands of the United Farm Workers were basic wages and necessities. After all, the eight-hour day wasn’t enough by itself, especially when bigotry and other forces worked to make sure many groups were left out.

That’s why we must pay attention to the other part of the equation as well, because the fight wasn’t just about the eight-hour day, or the vote. In order to move the world an inch away from hell, you start where you are, but you can’t lose sight of where you’re going. One falters without the other and given the forces arrayed against even the basic steps above, it is all too easy to slide back.

I write all that because if we start where we are, in the Asheville of 2017, the need for change could not be more clear. Despite many amazing people and culture, the second fastest gentrifying city in the nation is a paradise only for the well-heeled, overwhelmingly white few. The people of Asheville (without whose “brain and muscle not a single wheel can turn” as the song goes) are poorly paid even by N.C. standards, often with little recourse for abuse or mistreatment due to a lack of unions and labor law enforcement. The city remains brutally segregated, our immigrant neighbors face growing hostility and our leaders often see LGBT rights as something to be abandoned at the first opportunity. We show up on national lists of hunger, debt and a lack of affordable housing, a mirror that reveals the hollow nature of those shiny marketing tallies about what a great place we are to visit.

Too often, our city’s current political culture responds to these growing problems with complacency, a refusal to force even basic accountability from officials, a resentment of those who dare to speak up and pressure for a facade of compromise that inevitably calls on the well-heeled and established to give up nothing and the marginalized to give up everything.

There are many, many changes necessary to fight that, but it can be fought. Businesses can be boycotted, unions organized, communities rallied, the endless greed of the gentry fought block-by-block. Nothing is inevitable, least of all the loss of our city for those who make its existence possible.

I’ve spent over a a decade covering City Hall, and that too is where part of the focus should turn. Asheville’s government oversees the fate of over $160 million a year, along with broad powers over development, policing and many services. There is a reason the Fusionists, Seidel and the Panthers all turned their attention to local institutions as well as broader efforts and radical goals. City Halls are far more vulnerable to pressure from the people they claim to serve than many currently occupying positions of power in them would have you believe, their powers more quickly turned to different goals.

So here, after hearing from and talking to a lot of locals, are three changes our city needs. Each would only take a vote from our elected officials (either the current group or new ones) to begin. While far more is needed, they would start quickly saving Ashevillians from homelessness, putting serious power behind equity efforts and democratize the way decision-making is made at the ground level. It’s a start.

A rental crisis fund — Too often, a few hundred dollars is all that separates many of the people in this town from financial ruin or serious hardship. According to a massive 2015 study commissioned by the city of Asheville, over half of renters (and renters make up over half the city) are rent-burdened, meaning they pay over a third of their monthly budget just to keep a roof over their heads.

So Asheville needs to seriously back its own program to help counter the housing crisis by directly helping cash-strapped locals pay their rent.

This is not nearly as expensive or impossible as one might think, especially compared to some things our local government’s proved perfectly willing to drop money on. Assuming the program could cover about 20 to 60 percent of rent, depending on the severity of an individual’s situation, each $1 million that goes its way could help about 150 to 400 people.

The city’s efforts have so far focused on subsidizing the building of affordable units (though, some advocates have argued, not on the scale required to seriously curb the problem) but even if those programs work wonders, it will easily take a year or more for them to affect the housing supply. More far-reaching efforts like community land trust have some promise, but will also take years to set up. A rental crisis fund provides an immediate way for local government to help locals avoid eviction and, possibly, homelessness.

Such a program is totally, completely legal even under our state laws — I ran this by housing attorneys before I wrote this piece — all that is required is the will and the cash. While the city does have some limitations in its budget, none of them are insurmountable. A rental assistance program could be an alternative destination for the controversial $1 million proposed for expanded downtown policing.

Also, though it hasn’t been talked about enough, the city’s set to spend $2.5 million on staff pay raises in this year’s budget. Historically, senior city staff propose across the board pay increases and not surprisingly, this benefits senior staff the most. A 2.5 percent pay increase, for example, is under $1,000 a year for a starting firefighter, but over $4,000 more for a top city official.

So perhaps this year Council could only hand out raises to those making less than $60,000 a year, tell its more well-paid staff to hold off a bit and turn that towards a rental crisis fund. After all, city officials themselves have dubbed housing a crisis, and crises require extraordinary measures.

That could provide the city with even more cash to help local renters. Add in a one-time $1 million from its reserves (remember, this is a crisis) and hold off on hiring a few six-figure consultants and the city could possibly keep 500 to 1,000 people in their homes in the program’s first year.

These are rough numbers, of course, and there are other ways one could propose to reach the same level of funding for the same goal, but the point stands: local government has resources to do this on a scale that could be a serious help to entire areas, if it chooses to.

Assistance should be prioritized for those in neighborhoods, like Southside or many parts of West Asheville, on the frontlines of gentrification or those (like Montford and downtown) where it’s largely taken hold but still threatens to push out hundreds more. There, even just 100 or 200 people being able to stay in their homes would at least help blunt some of the effects of gentrification that are rapidly segregating communities further and provide the breathing space needed for other community efforts.

This help should also go directly to the people involved, after verifying income and their rent level, to avoid the stigma that landlords can bring to bear if they know someone is receiving assistance.

Housing is a right. Asheville is in a housing crisis. Let’s act accordingly.

Create an equity office with real power — After years of activism and the 2015 election helped put the state of black Asheville more prominently in elected officials’ minds, our city’s government opted to create an equity office, ostensibly to deal with the multiple issues the community had brought forward. They’re seeking an equity manager to head this nascent city department right now.

However, the push has been met with some justified skepticism. Right now, too many senior city staff have shown an aversion to democracy and responding to community concerns. Problems with staff accountability on fronts from transit to policing has some in the public understandably worried that this office will just end up another unaccountable place with a highly paid staffer at its head scrupulously making sure any community push disappears behind a welter of jargon and delays.

Equity is a massive issue in Asheville, and given the severity of the situation the city can ill afford business as usual on this front. If an equity office is the route the city’s going to go, that office needs to have real power and be able to hold the bureaucracy, businesses and landlords to account.

So amend the city charter to make the equity position on par with the city manager, attorney and clerk. That way the equity office head would answer directly to Council and be much more independent from those they’re tasked with scrutinizing.

Furthermore, the charter should also change to give the equity office the power to assess any major city plans — everything from changes to development, policing and housing — to make sure that they’re fighting segregation in Asheville, not increasing it. If the equity office doesn’t sign off on a policy change, it should require a super-majority of six Council votes to pass.

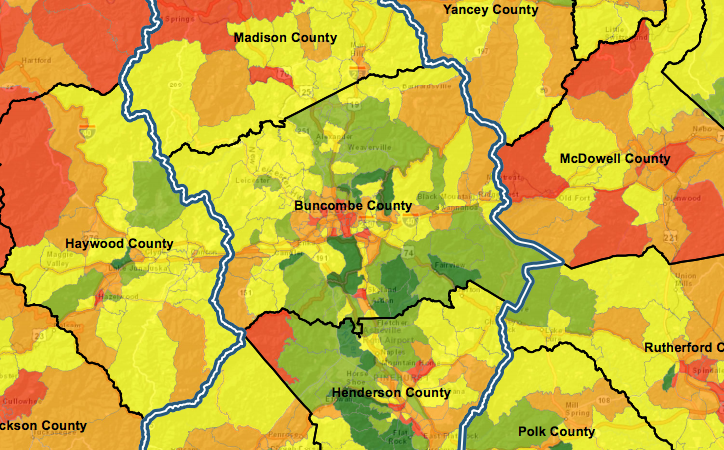

A map of city areas by median income, from the 2014 Bowen report. Red areas have a median income under $30,000 a year, orange areas under $50,000.

Staffing for the equity office should gear towards the kind of initiatives too often missing here: aggressively testing to see if landlords are offering minority applicants the same rates as white ones, delving into businesses practices that are discriminatory or furthering pay gaps. While these often run afoul of state and federal law, those injured by such bigotry usually don’t have the resources to press their case, and that’s where the equity office’s professional help could come in. When the equity office helps a local press for justice on this level, they should publicize it to bring sunlight to exactly what businesses or individuals are furthering discrimination in our community so local organizers outside government can bring pressure to bear accordingly.

If our city’s leaders are serious about equity, they need to show it and put real power behind changing how they do business.

Democratize the city’s boards — The people of Asheville are multiracial, multiethnic, multi-gendered and hail from right here in WNC to around the world.

The people tasked with making policy that affects their lives do not represent that reality. While attention mostly focuses on Council, the city has a welter of boards that directly shape how government works in a variety of areas. But the members of these boards are disproportionately white, male and wealthy.

Notably, on boards that have seen increasing diversity — like transit or police — senior city staff have pushed back considerably when newer members bring up major concerns, asserting that said boards need to be reined in or seeking to skip these committees getting to consider key issues entirely.

Once again, it’s clear that more serious reforms are needed. So far, however, the focus has mostly rested on making sure individual appointees resemble a more diverse group than their predecessors. That can leave those individuals, when they try to make change, stuck in the middle of boards that want to go about business as usual.

But with a few exceptions, boards are controlled by Council, who can decide to change the way they work — or their make-up — if they choose.

So instead of trying to diversify one member or board at a time, the city needs to wholesale scrap most of the current committees that aren’t specifically constrained by state law and start over with a sweeping reform. Reduce the number of committees, given them clearly defined powers, make strict rules for transparency, appoint representative membership and pick locations and times that are far easier for the public to attend.

An example of how this could work would be the Downtown Commission. Currently the commission meets on a Friday morning and its make-up leans heavily towards more well-off merchants and residents. Not surprisingly, the policies often advocated there reflect the views of the gentry, with the occasional dissenting voice. The Downtown Association, a private organization whose leadership has pushed some pretty controversial positions, even has an assured seat.

This could be replaced with a new, more representative committee, covering a wider area in the core of the city, meeting at a more accessible time and with seats assured for traditionally-ignored communities like public housing, Southside and the homeless instead of gentry-friendly organizations who already have plenty of say within our city.

Right now the powers of commissions, and if Council has to consider what they propose, is often left vague. Even some senior city staff want this situation to change, but they want to define the powers of boards to make commissions easier to ignore and, in some cases, have used the vague nature of a committee’s powers to skip going to it entirely.

The opposite needs to happen. Boards should have clear powers, including to directly recommend matters or proposals to Council itself even if staff objects. Combined with the other reforms, this would at least force Council and staff to address the concerns of communities that have too long gone ignored and give a wider array of locals more say in how our city runs.

—

These are only a start, of course. Most politics happen outside government. But it’s not a battleground that can be neglected. The above changes would impact the lives of thousands while curbing the power of the wealthy and unaccountable. That can work hand-in-hand with on-the-ground movements and give them a stronger hand.

At its heart, the power of May Day is, always, a reminder that the future can be a more just place than today and that the past holds countless dreams of better worlds that seemed impossible until the moment they became reality.

—

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by its readers. If you like what we do, donate directly to us on Patreon or make a one-time gift to support our work. Questions? Comments? Email us.