Veneration of the Confederacy is founded on lies about a brutal regime that terrorized millions. It’s long overdue to confront that history and the ways its evil still endures in our city today

Above: With drills and crow bars, activists try to dismantle the Robert E. Lee plaque on Aug. 18. Photo by Micah Mackenzie

Early in the morning on Aug. 18 four activists — Nicole Townsend, Adrienne Sigmon, Amy Cantrell and Hilary Brown — took crow bars and a drill to a plaque, attached to a squat stone marker in the shadow of the Vance monument, commemorating Robert E. Lee. The four were arrested, charged with a misdemeanor and released. Later that morning, organizers released the following statement:

Today marks a week since Heather Heyer was murdered in Charlottesville while resisting white supremacists who came to defend the Robert E. Lee monument. Heather’s death comes after years of black people being slaughtered by the police and white silence in the face of institutionalized violence.

One of the calls to action made by Charlottesville organizers was to remove all confederate monuments. Today, organizers in Asheville made the decision to answer that call by attempting to remove our Robert E. Lee monument.

We understand that the removal of this monument would be symbolic of removing white supremacy from the very center of our City. We know that this must be connected to the deep work of ending systemic racism and white supremacy culture here.

The move came less than a week after the violence in Charlottesville caused by far-right groups, including Nazis and the KKK, in response to the local government taking down a statue of Lee (and passing a $4 million reparations package). There, a terrorist attack murdered one activist and injured 19. A KKK leader fired at a black protester while police looked on, and clergy later credited anti-fascist activists with saving lives and preventing further bloodshed.

The four Ashevillians arrested have a long history in social justice movements, including the major fight earlier this year over Asheville’s budget. Their act also came days after protesters in Durham, to happily surprised reactions from locals, had pulled down a Confederate statue amid a growing push for cities and institutions around the country to do so. It happened after Mayor Esther Manheimer appeared to walk back an initial statement seeming to call for the removal of the multiple pro-Confederate monuments in Pack Square. The state legislature banned moving or modifying such markers in 2015.

Last week’s Asheville City Council meeting sharply illustrated the political divide. Our city’s elected officials unanimously passed a condemnation of the bigotry in Charlottesville, one that also promised to conduct a “timely review of policy recommendations in furtherance of this Resolution, including, but not limited to the review and consideration of the relevant General Statutes and other applicable laws related to historical markers and monuments on city property.” Manheimer also promised to “formulate a plan for public engagement around the monuments.”

“I really think we need to go further, condemnation of hate groups is easy, it really only amounts to words,” Council member Cecil Bothwell replied, adding that the motion’s move to study the question “just kicks it down the road.”

Instead, he wanted Council to state its intent to remove all Confederate monuments in downtown “one way or another.”

“It’s very clear from what happened in Charlottesville that hate groups consider monuments to the Confederacy and slavery to be very important symbols to them. I think we should deny those groups those symbols.”

“I don’t think we’re having the big conversation on monuments tonight,” Council member Julie Mayfield said, instead she wanted to look into the “legal obligations” surrounding them.

“We have to be very careful not to put the city into legal jeopardy.”

An APD officer observes protesters trying to take down a plaque to Robert E. Lee on Aug. 18. Photo by Micah Mackenzie.

Council member Gordon Smith said he appreciated the various opinions (without siding with any of them) and claimed “everyone at this dais is keenly aware things have to change.”

“Once you understand why these monuments were erected, what they mean, what they stand for, you understand they have to come down,” Council member Keith Young said.

Several locals spoke, all calling for the monuments’ removal or at least markers about the realities of their placement “as a first beginning.”

One speaker was Townsend, who asserted that “good intentions and liberalism are both modern-day nooses, except their victims don’t hang from trees.”

Instead of a proclamation to “save face,” she said, Council should take the calls of Charlottesville activists seriously, including “research to identify Nazis and white supremacists in our own communities and take down all Confederate monuments.” They should also, she cautioned, learn a lesson of history from the emancipation and civil rights struggles: some laws are meant to be broken.

“Had folks respected the law, there’s a possibility that they would have never seen the monumental changes that happened on the state, local and federal level as it relates to the rights of black folks in this country,” Townsend continued. “I am asking you to break unjust laws, I am asking you to remove Confederate monuments, I am asking you to align yourself with the platform of black lives, I am asking you to stop with your passiveness and take a radical action to make Asheville a sanctuary city.

“I am asking you to be on the right side of history and stop having conversations about it.”

Reality check

The Vance monument, the center of this political battle, is dedicated to Zebulon Vance, a politician who both fought and governed for the Confederacy. Despite his wartime rivalries with the regime’s officials, Vance’s post-war political agenda was still centered firmly around racism: a government run by “the good old Anglo-Saxon race” against “the descendants of barbarian tribes.” His political comeback was enabled by the KKK’s violence and he played a major role in laying the groundwork for Jim Crow, as did his longtime ally/rival Augustus Merrimon.

The obelisk was formally dedicated in May 1898. While that ceremony contained only brief references to his ties to the Confederacy, it was to a man who made bigotry the cornerstone of a long career. Importantly, it came just as white supremacists around the state ramped up a violent campaign against the multi-racial Fusionist movement that had pushed back against the order Vance built. That campaign would culminate in the bloody Wilmington coup d’etat and massacre late that year.

The monument’s prominence has come under criticism before, to put it mildly, with local African-American historians and leaders long pushing for it to be finally accompanied by monuments to the long-ignored contributions of their community or torn down entirely. Historian Darin Waters has repeatedly pointed out the ties of such monuments to the Jim Crow power structure and the ways their reverence works against a more democratic public space. While these perspectives haven’t always agreed on the exact route forward, the push for change is not new. In a recent radio interview Sasha Mitchell, the head of the local African-American Heritage Commission, reminded locals of Vance’s past. While noting that it wasn’t the route she would have personally chosen, she was glad Durham’s protesters had torn down the monument in their city.

The Lee marker is also telling. At first its presence may seem odd. After all, Lee had no ties to Asheville and neither he nor his army spent any time here during the war. Indeed Appalachia, including WNC, was a center of opposition to the Confederacy, one the regime responded to with repression and massacre.

The marker struck by the protesters’ tools was erected as part of the Dixie Highway (a response to the earlier Lincoln Highway) in 1926. Katie Gudger, the wife of a politician boosted into power by one of the plotters of the Wilmington coup d’etat, dedicated it. She hauled a historian up from Georgia to lecture on Lee, spoke of “far-reaching results” from the widespread veneration of “the South’s greatest hero” and intended the monument to send a “silent message through all the coming years.”

That’s the point. History’s portrayal is never neutral. Neither are statues or public art. The fact that the Lee marker was unveiled during a period with widespread lynching, black towns burning and a resurgent KKK is not a coincidence. Nor is the fact that it remains there today.

The message — in our still harshly segregated town — is telling, as is the repeated lack of movement by local officials on an overhaul of Asheville’s public space or a serious push to deal with the city’s mounting racial injustices.

The past shapes the present. What we believe about history, about how and why the world around us is the way it is, often determines the future. The Civil War is the most distorted event in American history, in no small part due to the relentless Lost Cause propaganda that followed the war.

Here’s the truth: the Confederacy was evil, without any redeeming characteristics whatsoever. It was founded on slavery and a social system formed around spoiled aristocrats despising both the enslaved and the “mudsills” who worked for a living. It made life some variety of hell for all but a small, awful elite who forced or duped others to suffer and die for their gain. Often incompetent as well as monstrous, the only things it has ever had propping it up were violence and lies.

Their cause was, as Ulysses Grant rightly tagged it “one of the worst for which a people ever fought.” That even readers who might not think of themselves as supporting racists or secession may cringe at the above words is a testament to how deep a century and a half of lies have penetrated.

But hundreds of thousands of Southerners hated the Confederacy and fought — often heroically and at great cost — against it (“rig the elections” isn’t a segregationist go-to because they had overwhelming public support). You don’t see their statues in every town square or often hear their stories told. That’s because the regime’s ideological descendants, taking advantage of a ridiculously lenient peace, stripped millions of their civil rights in ensuing decades of violence.

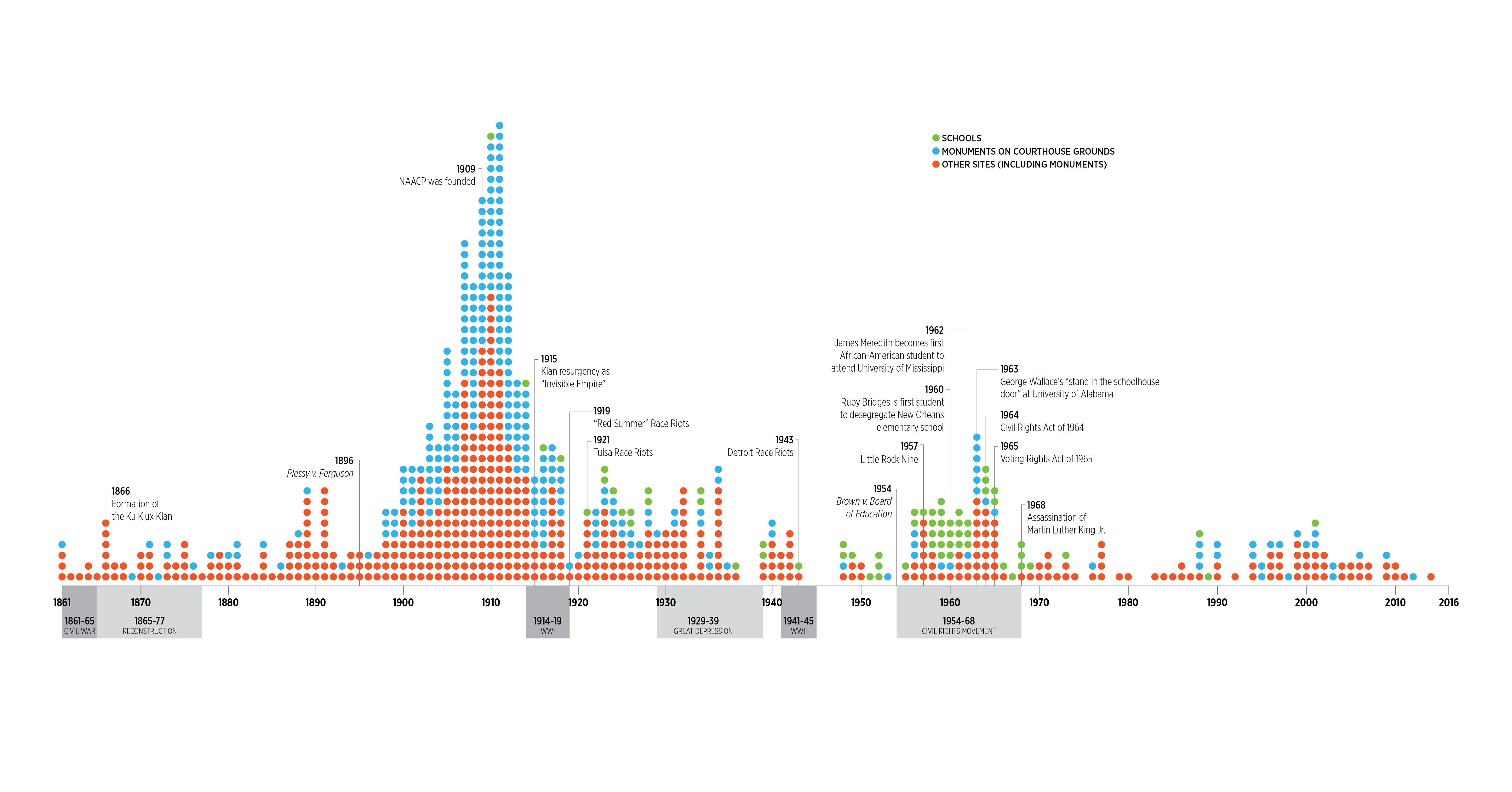

A graph from the Southern Poverty Law Center showing the context for when Confederate monuments erected. Larger version here.

The statues are part of that, the literal capstone on a horror that endures in many other ways, including in far more of the political reality around us than many want to admit. The Trump supporters that brandished Confederate flags in downtown Asheville last year knew exactly what message they were sending.

What we need is not reconciliation but reckoning. We need to face the reality of Lee, of the regime he fought for, how Vance and Merrimon revived it and how its legacy still infects our world today.

The gilded general

I didn’t grow up with a family that was particularly nostalgic for the Confederacy. Northeast North Carolina, like Appalachia, was actually a center of opposition. While I didn’t learn about the specifics of the multiracial maroon communities and Unionist farmers that had given the Confederates hell, I knew that many locals hated the regime, even joining regiments as far afield as Iowa to come back and fight it. My grandfather pointed out the occasional grave of one of the Confederate soldiers who’d killed Unionist families and emphasized that he was in hell.

But a century’s worth of propaganda has an effect. While they were outspokenly against segregation during its height, the myths had spread deep enough that my grandparents made an exception for Lee. I heard that he wasn’t really for slavery and secretly deplored segregation. Even then, something seemed deeply off about the whole explanation, but it was constantly repeated to the point of consensus, even by people who called themselves liberals or progressives.

It wasn’t true. Indeed, no part of Lee’s mythology holds up to scrutiny. Earlier this year, journalist Adam Serwer provided an invaluable summary.

Here’s the facts: Lee owned slaves. Indeed, he used a legal loophole to avoid giving them the freedom promised in his relatives’ will. According to them, he was even crueler than their previous enslavers. He broke up families and had his overseer torture those who tried to escape. His letters are full of references to his deep conviction in both the inferiority of African-Americans and that enslavement was for their own good. He occasionally expresses vague worry or concern about how awful the whole institution is, in that “look what you made me do” way immediately familiar to survivors of abusive people and systems.

After turning coat on the country that had provided him with a career his entire adult life, he led an army that had the highest casualty rates in the war (no mean feat in a conflict that ugly), partly because of his penchant for vague orders and really dumb frontal assaults like Gettysburg. During the war his soldiers terrorized and enslaved free blacks. He sanctioned atrocities against black Union soldiers, even when it cost his army dearly needed manpower by ending a possible prisoner exchange. After the war he fought against black civil rights and the university he ran hosted an active KKK group that terrorized black people in the surrounding area. Despite finding ways to strictly govern every other aspect of his students’ conduct, he somehow never raised a finger to stop them from running a terrorist cell.

So Lee became the patron saint of “redemption,” the widespread use of terror by ex-Confederates and their sympathizers to crush Reconstruction and civil rights. Lee put a genteel face on a horrific system, one it used to take advantage of American society’s constant forgiveness of both violent racism and any crime perpetrated by rich men in oil paintings. Lee statues cropped up like flies on shit with each crushing of a push for civil rights, his actions were whitewashed in film and media, and the Lost Cause line relentlessly regurgitated even in histories gobbled up by those outside the South.

It was horseshit, of course. The defining issue of his time was the fact that millions of people — including plenty in the South — were locked in a fight about the future of slavery and the society based on it. He picked his side.

Lee’s myth is still used to blunt any push to reckon with past and present, to make it seem like there’s something noble about what he did and fought for. It wasn’t coincidence that Nazis and the KKK gathered around his statue in Charlottesville; he remains the icon of segregation.

‘Every last one of them should be killed’

Indeed, to put up that edifice of lies, the “redeemers” had to declare war on the past as well as the present. They had to eradicate the history of the antebellum period, of Southerners who fought against the Confederacy, of the black liberation struggles that made slavery a dying system on the ground and pushed emancipation towards reality. Finally, they had to erase the reality of their own actions after the war.

Occasionally there’s a historical marker to the above, but rarely the kind you see for the regime. Indeed, there’s one such small memorial just north of Asheville, in Madison County, to the Shelton Laurel massacre. I recently wrote about this massacre for Scalawag, and it’s an atrocity reveals the reality of one area the Confederacy was particularly despised: Western North Carolina.

Contrary to later mythology while there weren’t as many slaves in WNC as the rest of the state, they weren’t absent either: they played a key role in the emerging economy, their numbers were growing and local elites were overwhelmingly slave holders. Those aristocrats held a lock on offices from sheriff to senator, with justices of the peace often holding their jobs for life and meting out punishment as they saw fit.

This wasn’t unique. John C. Calhoun, the South Carolina politician who laid the groundwork for the “fire eaters” that rabidly sought slavery’s expansion and infliction, coldly talked about kicking poor farmers off their land to make room for even bigger plantations.

It took a massive act of historical erasure to ever make the Civil War seem as if it was about something other than slavery. The antebellum period is full of future Confederates thundering about slavery, clamping down to preserve slavery, demanding slavery be enforced in anti-slave states, swearing to “burn, shoot and hang” to create more slave states and seeking to build “an empire for slavery” (their words) in Latin America.

That’s why it’s accurate to speak of a “slave power” or a “slave society,” with slavery at its heart and a multitude of oppressions ringing it. It takes a lot of effort to be that actively horrible to other human beings, so such systems have multiple levels and hierarchies that can be used to divide and control. That is the point of them.

Pushed to the margins, many mountaineers formed an identity tied to country rather than the state and local governments run by people they hated. Some hated the enslaved as well as the slavers. While an outspoken opponent of the Confederacy, for example, Appalachian Unionist Andrew Johnson would prove an enemy of civil rights after the war. But others, like an Ashe County conscript who eventually deserted to the Union army along with 25 of his fellows, condemned “a government that seeks to enslave me and whose cornerstone is slavery.”

From the start, the new regime brought home tactics of massacre — already honed on the indigenous, the enslaved and abolitionists — against suspect mountaineers. The murders of local “Lincolnites” in rural mountain counties even pre-dates North Carolina’s formal secession. Outgunned, Unionist guerrillas struck back hard with assassination and sabotage. The region’s inhabitants were divided, but by 1862 a Confederate general in Madison County was already writing that “the whole population is openly hostile to our cause.”

So as that year wound to a close the Confederates seized the local supply of salt — necessary to surviving a mountain winter — and hauled it to Marshall in an effort to inflict “great suffering” on the pro-Union countryside. Desperate to take revenge and save their communities, a band of Union guerrillas seized the town, shot the officer guarding the salt and pillaged the homes of the commanders of the regiments that had terrorized their communities.

In response one of those units, the 64th North Carolina, sought revenge. The results reveal much about the Confederacy’s attitude towards any Southerners opposed to it.

The atrocity was approved from the highest levels. Gen. Henry Heth, a personal friend of Lee’s, ordered that “I do not want to be troubled with prisoners and every last one of them is to be killed.” The 64th attacked the pro-Union Shelton Laurel community, tortured the elderly and mothers who remained, burned their homes and took their food. The soldiers eventually hauled out and murdered 13 people, mostly old men and teenagers, in a spot chosen for its visibility. It was a tactic familiar to similar regimes throughout history: kill, terrify and starve a community, scatter them into a hard land in a harsh season so even more will die.

The rest of the 64th’s war is revealing, because it’s a unit that would be immediately dubbed a death squad if its actions were carried out in any other time or country. They specialized in “caustic measures,” as one officer later put it: burning homes, summary executions and terror tactics to put down “the disloyal sentiment.” Eventually mashed up ad-hoc with a similar regiment, it remained in Appalachia until the end of the war, guarding planters’ summer homes and inflicting violence on the locals.

Similar massacres were carried out from Texas to the North Carolina coast, signs of a government desperate to cling to power despite broad swaths of the South hating it, an anger that only grew as it demanded more of their lives and food for their failing armies.

Importantly, both Vance and Merrimon play a role in the response to Shelton Laurel. On the surface, they condemned it and sought to convict the 64th’s commanders of murder.

But on a closer read it’s apparent this wasn’t because of any real aversion to civilian bloodshed; they’d inflict plenty of that in the years to come. Like their clashes with the Confederate government, it was because they were canny operators seeking to save their own hides and prop up a system that gave them power. They also wanted to avoid retaliations that might fall on their holdings and families. Recent evidence shows that Merrimon likely also had a pre-war grudge with one of the 64th’s commanders.

Vance’s love for the area’s people was so deep he agreed with much of a proposed Confederate plan, broached around the time of Shelton Laurel, to force march most of them to Kentucky. He added his own cruel twist: women, children and the elderly should be kept behind as hostages.

None of the 64th’s leaders ever paid for their atrocities. One, despite being wanted by the state government, went back to leading an informal death squad in the last years of the war, to approving write-ups from Asheville newspapers. Later, as a U.S. Senator, Merrimon brought up a bill to recompense the survivors but then quietly killed it. In 1966 the people of Shelton Laurel paid for a gravestone to the dead, alongside a small state historic marker on the highway.

The old devils are at it again

“When anyone talks about an era of peace and prosperity, ask where the bodies are buried.” — Saladin Ahmed

Despite all that atrocity, the Confederacy lost. Resistance in the area only grew as time went on. Black highlanders both slave and free proved a key network of information and support for the Union cause. Drained by the raids of guerrillas, hit hard by experienced Appalachian Union regiments (including those made up of many mountaineers they’d driven from their homes) and suffering from the corruption and incompetence rife throughout their government, the regime lurched to defeat after defeat. On April 26, 1865 both Union soldiers and liberated black Ashevillians marched through the center of the city in victory.

If Vance and Merrimon had truly thought slavery wrong or regretted any of the war’s atrocity, they could have turned their backs on it then. Some Confederates did: James Longstreet, once one of Lee’s top generals, switched his support and later helped fight the White League terrorists in New Orleans (no, he doesn’t get many statues).

Instead, they immediately started using their political cunning to bring the regime back.

This wasn’t unopposed. Realizing, as one Unionist petition put it, that “secession is still rampant in this section of the State and although its authors have been whipped they still seem determined to Rule,” some black residents of Buncombe County armed themselves and set up patrols to protect their communities while other local Unionists formed working-class self-defense societies like the Red Strings. As a post-war judge Merrimon was particularly active in trying to put down these groups, blasting them as a “lawless element.”

There was a bitter irony to those words. From his judicial perch Merrimon refused to grant black citizens their newly-guaranteed legal rights, instead railroading them through sham trials to use as free labor for his relatives. This only ended when a Freedmen’s Bureau agent forcibly intervened. The practice, which Merrimon and Vance both encouraged and profited from, would later return across the South, making a mockery of the promise slavery had ended and helping to lay the foundation of the modern prison industrial complex.

Vance encouraged the KKK’s aims and his return to power was enabled by their violence. In 1868 he secured his position as one of the chief political leaders behind the Conservative party (as the state’s Democrats were dubbed) and “toured the state urging white North Carolinians to rally in support of their white skins.” Even his 1870 “Scattered Nation” speech, ostensibly calling for religious tolerance and an end to anti-Semitism, denigrated African-Americans in an attempt to divide them from the Jewish population.

As KKK violence ramped up, Merrimon defended the terrorists pro-bono and helped coordinate the 1871 impeachment of Gov. William Holden. Holden’s crime? Trying to bring the KKK to justice after they lynched a black town commissioner and terrorized the state.

Following Vance’s plan and bolstered by Merrimon’s scheming, the Conservatives pushed for an 1875 convention to gut the Unionists’ state constitution, amending away many of its guarantees of civil rights. The Conservatives rigged election results in a key county, clawing out a narrow majority of the convention’s delegates. They promptly banned interracial marriage, segregated public schools and re-centered power over courts and local government in the legislature, “giving them majority control of political offices across the state that was not justified by their actual electoral numbers. For decades they were able to effectively squelch opposition.”

Elected governor the next year, Vance went further. In 1877 he abolished local elected government, giving state-appointed justices of the peace complete control over local commissioners as a way to crush civil rights. The new railroad that ran through WNC made his property even more valuable, and when funds ran short he insisted on using black convict labor — largely those detained on bogus loitering or vagrancy charges — in lethal conditions.

Merrimon and Vance would later continue their careers into the U.S. Senate, playing key roles in stopping federal intervention against the terrorism racking the region. Both were among the chief architects of Jim Crow, responsible for killing or ruining the lives of hundreds of thousands of people throughout their long careers. That is the only way they should ever be remembered and indeed, that’s why state elites loved them at the time.

As much power as they gained and as viciously as they wielded it, resistance didn’t end. With Merrimon dead in 1892 and Vance in 1894, the state’s Populists and Republicans struck back, forming an interracial alliance known as the Fusionists. Drawing support from many of the regions that had fought the Confederacy, they swept local and state offices in 1894. They returned control to local governments, started pushing back on civil rights, put funds towards education and curbed unfair contracts.

Vance’s monument was dedicated in 1898, amid a massive statewide campaign to claw back the old guard’s control from the popular movement that suddenly challenged it. That effort won back office through widespread racist violence culminating in a coup d’etat in Wilmington, with the massacre of black citizens and the exile of white Fusionists. Overnight, Wilmington ceased to be a majority black city and civil rights was buried for a generation. Given their long, hateful careers, Vance and Merrimon would have approved.

The past ain’t past

There’s a lot in the stories above, much of it tragic. But this is the history that must be faced, the actual history of how we got here.

If it seems like a surprise, that’s only because it was erased.

After all, there’s no monument to WNC’s two hard-riding Union regiments in the middle of Asheville, or to the triumphant march through the center of town that accompanied the end of slavery, no memorial to the communities formed in emancipation’s wake or the tragedy of their demolition. The history of Confederate massacres is tucked aside, when mentioned at all. Dedications to the Virginian commander George Henry Thomas, who rejected his slave-owning family and spent the next decade annihilating Confederates and the KKK, do not dot Southern towns. No statue of the brilliant radical political and military leader Abraham Galloway, who declared the need to fight with both “the cartridge box and the ballot box” stands in Wilmington’s place of power, nor markers to the maroon resistance fighters in Elizabeth City’s. Sculptures of Harriet Tubman’s heroic Combahee raiders do not dot the South Carolina coast. Charleston harbor is not named after Robert Smalls.

This is not an accident.

Nor are the Confederate flags flying in Michigan and New York, or a spoiled Yankee aristocrat referring to the regime’s crimes as “our heritage.” Plenty of the country was fine with violent racism, happy to turn a blind eye to the Confederates creeping back, even adopting the ideology for themselves. The 1920s KKK revival was, after all, nationwide.

The ugly secret is that the cause that put those statues up endures in far more of our politics than we like to believe. Growing up, I saw Confederate “historic societies” and re-enactment groups used as a cover for far-right organizing, often espousing perspectives right out of a Vance speech. They weren’t burning crosses, but they didn’t have to: their members owned businesses, ran police departments and held office.

Occasionally the mask slips. The League of the South, one of the white supremacist groups in Charlottesville, splintered from one of those historical groups. It bluntly declared its commitment to a “natural societal order of superiors and subordinates,” with plenty of misogyny and class hatred thrown in alongside the racism.

Of course, many of the monuments’ defenders don’t voice similar views quite so publicly. So at first they’ll claim “it’s just history,” that the statues are no big deal but have been up so long that they’re somehow beyond question. If anyone points out the actions of the people they commemorate, you’ll hear “sure, he was a violent racist, but he wasn’t a complete anti-Semite” or some such tangled drivel.

Yet for such a supposedly minor, bygone thing the same people are awfully insistent on making sure those monuments stay up at all costs. They’re very keen to pass legislation banning any change, hunt down activists and charge them with felonies. Hit the right Facebook thread and you’ll find them repeating Vance’s lies and even outright calling for massacre. Eventually — as in Charleston or Charlottesville — some of them try to carry it out.

Not all remnants of the Confederacy are so blatant. The state legislature’s control over local government — still used today to halt multiple civil rights efforts — dates from Vance’s groundwork for Jim Crow. North Carolina’s laws no longer contain poll taxes, just relentlessly gerrymandered districts intended to crush the black vote “with almost surgical precision.” African-Americans still face violence and the violation of their rights from forces both inside and outside the legal system. Red lines, springing out of the same mentality that fueled the Klan’s 1920s resurgence, still mark neighborhoods in our city today, as does the obliteration caused by urban renewal.

The past ain’t even past.

Here’s the truth: their defenders want the monuments to stay up because they agree with the Confederacy. They don’t believe slavery was a great evil because they don’t value black lives. They genuinely believe that white men, no matter how incompetent or spoiled, are better than everyone else. They believe that the people “redemption” oppressed and killed still deserve to be oppressed and killed.

They wish the Confederacy’s defeats had never happened. They believe that the movements for liberation people like Vance crushed needed to be crushed and still fear their renewal.

They are right to fear it. There are and always have been people willing to fight back against the Confederacy and its heirs. From Ashevillians facing down Trump supporters and burning a Confederate flag last year to the happiness in Durham as the statue fell, plenty of the South is sick of their crap because the society they want to reinforce is a goddamn nightmare.

These links were obvious in Charlottesville itself. While it received far less coverage, the dismantling of Lee’s monument was paired with the passage of a $4 million reparations package, including funds to start addressing the destruction caused by “urban renewal.” This was pushed hard by locals demanding that the structures of racism be demolished along with its symbols.

However, the city government’s commitment to justice did not extend to forcefully and immediately expelling Nazis and the KKK from their town. People are dead because of that. Instead, locals and left-wing activists stepped in to save lives and stop fascists. People are alive today because of that.

That too is revealing. The push for justice, the one the whole Confederate project was devoted to destroying, has another old obstacle: complacency even from people who claim to sympathize with its aims. That’s why supposedly anti-Confederate officials passively handwrung their way through atrocity after atrocity while civil rights were annihilated for nearly a century. It’s why many of these monuments still stand.

The same problem underlies why Asheville’s progressive Council was just fine with working with Confederate re-enactors to refurbish the Vance monument, partly at city expense, why “progressive” writers here were too often willing to whitewash his crimes, why our city’s segregation isn’t regarded as a true crisis by many of our leaders, why even today there are well-heeled in this town whose rants against the working people of this city might as well call just go ahead and call them mudsills.

Each report on the State of Black Asheville shows a city where Vance’s segregationist set-up is still very much alive.

The monument question is something many local leaders wish would just go away as it frustrates their desire, above all, to provide a city of comfort for the comfortable. It’s a political battle that raises questions — uncomfortable ones — about the realities above and their repeated failures to seriously address them.

In trying to blunt the pushback to their passivity, it’s common for white “progressives” (who want injustice to end someday, eventually, maybe after sufficient study) to invoke mythically docile versions of King and Mandela. I have zero doubt we’re about to see that again as this fight stretches on during the coming months.

They would do well to mark King’s actual words:

I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen’s Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to “order” than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says: “I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I cannot agree with your methods of direct action”; who paternalistically believes he can set the timetable for another man’s freedom; who lives by a mythical concept of time and who constantly advises the Negro to wait for a “more convenient season.” Shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will. Lukewarm acceptance is much more bewildering than outright rejection.

I had hoped that the white moderate would understand that law and order exist for the purpose of establishing justice and that when they fail in this purpose they become the dangerously structured dams that block the flow of social progress.

They should heed Mandela’s too, while they’re at it. He helped pen a warning that still rings through the decades:

“The people’s patience is not endless.”

—

In addition to the pieces linked throughout this article, these works below helped inform this article, and are invaluable resources to counter the edifice of lies embodied by the monuments.

Life Beneath the Veneer, Darin Waters, a detailed look at the history of African-American community in Asheville and WNC.

Battle Cry of Freedom, James McPherson, an excellent one volume history of the Civil War as a whole, including the decades leading up to it and the nature of both the Confederacy and the abolitionist cause

Reconstruction’s Ragged Edge, Steven Nash, detailing post-war political fights and the rise of the KKK in post-war WNC

Victims, Philip Shaw Paludan, a detailed look at the Shelton Laurel massacre

Democracy Betrayed, an essential collection of essays on the Wilmington massacre/coup d’etat and the community it sought to crush

—

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by its readers. If you like what we do, donate directly to us on Patreon or make a one-time gift to support our work. Questions? Comments? Email us.