A thicket of complicated issues, from the Airbnb spectre to a bus system overhaul to the “fake repeal” of HB2, hit City Hall during an unusual summer

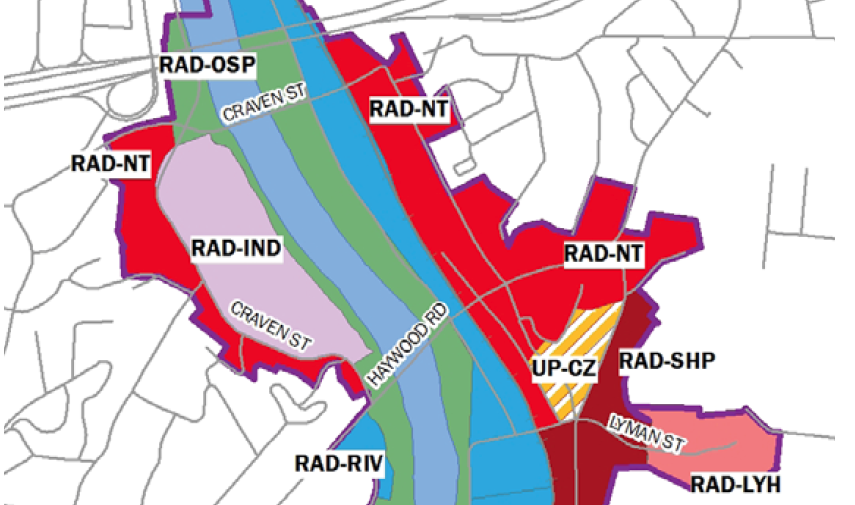

Above: a portion of the city’s new zoning maps for the River Arts District

This summer’s not been a typical time on the city politics front. There were about half the usual Asheville City Council meetings — just three in three months, on July 25, Aug. 22 and Sept. 12. Two of the three wound on for over four hours. Yet despite the length of those meetings, and despite a busy election season, there was no single issue that emerged to run up the time or result in major fights like those seen earlier this year. After a spring that saw a massive citywide political battle over racism, policing and the budget, Council largely descended into a bramble of complicated zoning, infrastructure and resource issues.

Yet complicated as these issues may be, they’re no less important and they did provoke plenty of feelings and disputes. They affect whole swaths of the city, show serious obstacles on some major goals, reveal shifting reactions to public criticism and come down to things as basic as “can an Ashevillian find a parking space” and “does the city sanction discrimination?”

So, in an effort to better understand the forking vines of these various issues, here’s some distilled summaries of what’s going on, what it means and why it sets our local government up for a very conflicted Fall.

Carving up the RAD

The heavy-hitter issue during this strange summer season was the rezoning of the River Arts District (or RAD). The area’s been a major focus of successive city governments eager to replicate the revival of downtown near the river, encouraging a mix of dense commercial, residential and tourist—friendly development. The fact the area also bears the marks of a longtime industrial district and brutal racial segregation also play major roles in complicating Asheville government’s vision of a pristine, prosperous area that can enrich their coffers.

The rezoning is a big part of that, paired with a massive (and troubled) infrastructure overhaul. Zoning’s one of those major areas of city policy that seem dull until you realize that where and how things can be built and used is in fact one of the most important things local government controls. In this case, the city’s trying to put in place a “form-based code” which focuses more on the design and structure of new development rather than uses (like industrial or residential) that are the target of traditional zoning, In theory, form-based codes are supposed to be friendlier to dense, mixed-use development (downtown and Haywood Road both have such codes already in place). They’re more about “how buildings relate to the public realm and less about what goes on inside,” as city planner Sasha Vrtunski put it.

But while the infrastructure plans are, amid a slew of controversy, getting an overhaul and proceeding on a far more limited scale and schedule the zoning effort, on July 25, look set to plow straight ahead.

It didn’t.

The city’s effort to rezone the RAD hit two major hurdles. The first was opposition from the remaining industrial business owners in an area that’s saw an increasing number of parks, artist studios, residential development, businesses and restaurants. They claimed the new zoning rules would make their business impossible and push a good-paying economic sector out of its traditional home in favor of trendier fare.

“I have a concern with the potential loss of industrial zoning along the river,” Mac Swicegood, a real estate appraiser and conservative activist, told Council. “To burden these businesses down with more zoning regulations could put some of these businesses in peril with nowhere else to go.”

“‘We’re going to build a Disneyland on the river and we’re going to run all those people off,'” developer Jerry Sternberg, speaking on behalf of a group of “the River Rats,” a “loosely-connected” band of industrial business owners, summed up his view of the city’s goals. “These aren’t fancy buildings on the river, these are the people that do the grunt work, the hardest parts, they service the city.”

The rules, as originally proposed, allowed current industrial businesses to remain, but could make it more difficult for them to expand or renovate.

The second obstacle was, if anything, even trickier. While not the primary focus of the rezoning, the whole effort ended up walking straight into the minefield that is “short-term rentals” the city’s jargon term for Airbnb-style rentals that cater to tourists and visitors.

In most areas, such rentals are banned if they rent out a whole home or apartment (as repeated investigations have found that many do in the city’s current tourism boom), though they can be allowed (with a permit) if it’s the property’s occupant renting out a room or small portion of the home they live in while they’re there, a practice the city calls “homestays.” This was the city’s attempt to split the issue, supposedly giving relief to cash-strapped homeowners while shutting out the many (perhaps most) Airbnb landlords that own multiple properties and want to rent out whole apartments and homes.

But there’s a catch. In some areas, renting out whole homes and apartments in this way is totally legal. Downtown is a major one. Another is the RAD.

Those exceptions have become a major flashpoint in this issue, as both areas are home to an increasing amount of residential development. In downtown, Airbnb-style rentals have already essentially ended some mini-neighborhoods like Chicken Alley by kicking out local renters and replacing them with units dedicated to tourists and visitors. Since over half the city are renters and housing costs are already sky-high, opponents of short-term rentals have long pressed for the ban in the rest of the city to be extended to those neighborhoods as well.

But Airbnb owners like making money and assert that denser, mixed-use commercial areas their ability to do so at a dramatic rate is more “appropriate” than in other nearby neighborhoods. This set the stage for a clash when it came to rezoning the RAD, as the original proposal didn’t just call for continuing to allow whole home/apartment rentals in the vast majority of the area where it’s already permitted, but actually slightly expanding the area where they’re legal.

“We are strongly in favor of this and we hope it’s voted in,” Hannah Choueke, speaking on behalf of a group of 11 Craven Street property owners, said. “We believe in allowing local citizens to capitalize on Asheville’s tourism economy while many new high-rise hotels are being built.”

She also claimed that local property owners already faced major nuisance issues from the tourism trade in the area and didn’t think STRs would worsen the issue any further.

While this fight has been a major, city-wide issue for several years, Vrtunski told Council that it hadn’t come up as a major concern in the long deliberations with local property owners about rezoning the RAD. Instead, she claimed, it had only come up as a larger concern during the Spring.

‘Asheville’s for Ashevillians:’ City Council member Gordon Smith supported curbing Airbnb-style short-term rentals, . File photo by Max Cooper.

After some back and forth, Council did — in a concession to the industrialists — agree to leave the area between the railroad and the river out of the new zoning plans until more was known about the future of rail transportation in the area.

But the close split on Council over the short-term rental issue remained.

“This is a big deal,” Council member Gordon Smith said, thanking past Councils, staff, the industrialists and the residents for good measure. “It’s a pivotal moment. I predict we’re going to see another half billion dollars, with a ‘b’, coming into this river district. There’s about to be a massive influx of investment down there. That’s why we have to do this now.” To that end, he supported moving forward with the changes while exempting the railroad area and banning short-term rentals in the RAD.

“Asheville’s for Ashevillians and if people from out of town like that then that’s great, we welcome them to come enjoy the thing we’ve built for ourselves, but we don’t build it for tourists. We build it for us,” he said. “I don’t have anybody coming to me and saying ‘what we need is to fill up an area of town with by-right tourism housing…this is not a tourist-only zone.”

He said that if property owners wanted to rent out whole homes and apartments to tourists, they could ask Council for approval to do that in the RAD on a case-by-case basis. Vice Mayor Gwen Wisler also criticized Airbnb-style rentals as inconsistent with the city’s goals. Mayor Esther Manheimer emphasized that with the wave of development on the way, the city needed to plan very carefully for the RAD’s future and take action now.

Council member Cecil Bothwell said that with Duke Energy ending its coal-fired plant, there was a possibility of a future explosion in container shipping in the coming years, making the railroad potentially a far more important economic asset than before.

City Attorney Robin Currin asserted that with the short-term rental changes included, the rezoning would have to go back to the Planning and Zoning Commission for another look.

Council member Keith Young opposed the short-term rental move, saying he didn’t feel such a bar to whole home/apartment rentals to tourists was “pragmatic.”

The rezoning, minus the railroad area and with a bar on whole home/apartment short-term rentals, passed 4-3, with Bothwell, Young and Council member Brian Haynes against.

But things didn’t get any easier for the rezoning from there. On Sept. 7, the Planning and Zoning Commission completely disagreed with the city on both the short-term rental and railroad issue, recommending that the city adopt the original plan it considered in July. That sends a flashpoint issue back to Council in the context of a clash with one of its most powerful committees. Unusually, Council won’t consider the RAD issue at its meeting this Tuesday, Oct. 3. Instead, the vote will come after the Oct. 10 primary, meaning that events at the polls could have a major impact on the fate of the RAD in City Hall.

Parking vanishes

While on paper it was only a hearing to allow temporary gravel lots in downtown, the Sept. 12 hearing on that issue ended up seeing a barrage of criticism from local business owners and non-profit heads about the dire lack of parking downtown and how it was hitting local workers and residents particularly hard. The lots, planning head Shannon Tuch pointed out, were only a stopgap, “temporary in nature” (partly due to the environmental and space concerns with them) until a “larger, more comprehensive parking solution” came along.

“I can’t overstate the difficulties that lack of parking creates,” Michael Whelan, one of the managers of the Orange Peel and a downtown resident, said. “It’s a constant problem with having people illegally park in our lot. I have friends that don’t live downtown, I’m constantly hearing from them that they don’t want to come down here because they can’t find a place to park. It’s a constant problem.”

“If the staff can’t get to work, we can’t fill the needs for our business, staff parking has become almost impossible,” Mast General Store manager Carmen Cabrera said. “Without public transit that accommodates the hours the store is open they’re forced to drive.”

“If they can’t live downtown, if they can’t get to work to downtown, this is going to be an even worse problem in two years.”

“We’ve been on that block for nearly two decades, we’ve watched the city change quite a bit,” Adam Thome, one of the owners of 67 Biltmore, said. “In order for us to succeed, all of us collectively, we need the city’s support for this parking issue. Parking effects two of our most important pieces to our small business puzzle: our customers and our employees. The most frequent complaint we’re hearing from both parties has to do with parking.”

“We have a lot of customers who tell me in the grocery store “we tried to come to your store but circle around, circle around and can’t find a parking space,” Emoke b’Racz, owner of Malaprop’s and Downtown Books and News. “The parking situation is tough for small businesses that are downtown. I’ve been watching this for years and I haven’t seen much improvement in making sure that the unique flavor of downtown is protected.”

“I’m glad there are so many people here to talk about this issue, but I don’t sense that it’s very controversial,” Manheimer said as Public Interest Project’s Karen Ramshaw came up to the podium to speak.

“Part of it is, I think, that people feel like they haven’t been heard,” Ramshaw replied.

“That is what the function of this process is,” Manheimer said.

“We do not have a parking problem, we have a parking crisis,” Ramshaw said.

Using data from a city parking study, Ramshaw asserted that Asheville had failed to keep up with growth, with far less parking spaces than similar-sized cities with less tourist trade.

“With Greenville and Charleston it’s two vehicles competing for each city-owned space, with Asheville it’s almost eight,” Ramshaw continued. Downtown groups and the city’s own parking studies from 2008 had called for more investment in parking spaces.

“Today there are waiting lists for the parking garages that are years, yes that’s plural,” she said, and other recommendations from the 2008 parking study, like satellite lots or purchasing land for parking had been ignored.

“Lack of parking hurts locals, many of our neighbors work downtown, but parking is unavailable or unaffordable and the simple act of getting to work is stressful,” Ramshaw said. “Many downtown jobs are not 9-5 and the cost of housing drives folks to the further reaches of the county so transit isn’t a realistic option for many downtown employees. Tourists will circle 20 minutes or pay whatever to park downtown. Locals won’t.”

And that, she said, was shutting locals out of the downtown they built in their own city, and only luxury developers would pay the extra cost to build separate parking, shutting out other housing and small businesses.

“You might as well roll out the carpet for the chain stores.”

The answer, she said, were taller city-run parking decks, which she claimed could replace surface lots while boosting activities in surrounding properties. She used the public-private partnership between Aloft Hotel, Public Interest Projects and the city to build hotels, housing units and a parking deck on the same site. City officials had failed to lead, especially as city staff reserved 15 percent of the spaces for themselves. “What if we turned those spaces over to downtown service workers and let the city try to run a business without parking?”

Manheimer said some of the problem might alleviate soon as 600 spaces in a Buncombe County-owned deck in the new Department of Health and Human Services came online.

“I know there’s some question if those spaces will be available on nights and weekends,” she said, and hoped staff could follow up.

Open space shuffles

Both the August and September meetings saw a complicated dance play out in an effort to build some affordable housing in Shiloh. The whole back-and-forth illustrates some of the challenges of trying to do so when rules are generally set up to favor traditional property owners.

The city has open space requirements in an effort to preserve Asheville’s tree canopy and prevent what planners see as an overly-crowded urban space from emerging. Usually, these requirements assume that the property owners are going to take care of and have access to the open space, either through the management of an apartment building or a homeowners’ association in the case of a privately-owned subdivision.

The question got more complicated, however, when local housing non-profit Mountain Housing Opportunities tried to set up a development that would allow those in it to purchase their own homes. This was part of the non-profits’ efforts to encourage affordable home ownership as well as rental units. However, to offer them at an affordable rate, they claimed, they couldn’t incur the extra expense of setting up a homeowners’ association.

That left a conundrum: the city’s rules require open space and someone to manage it, but MHO’s model didn’t have an easy way to do that.

At Council’s August meeting that effort bogged down. MHO variously proposed that each homeowner might oversee a portion (which would be almost logistically impossible with an open space) or that the Shiloh Community Association could manage it (representatives of the group were open to the idea but wanted to know far more details than were available at the time).

While the issue was resolved quickly on Sept. 12 as MHO representatives indicated they would make the open space technically a 21st lot with its own homeowners association to get around the conflicting legal requirements, it does illustrate the challenges to future affordable housing efforts. Whether land trusts or plans for cash-strapped homeowners, they collide with a legal system still set up to be far friendlier suburban-style development for the well-off.

Union, bus rider advocates gain victory

July 25 saw another major shift as well, the culmination of a long fight rather than the continuation of one. In this case the future of the transit system entered a new phase.

Since 2008 the Cleveland-based First Transit had managed the city’s bus system. Due to a conflict between state and federal laws, the city government can’t directly manage the system staffed by unionized workers.

Over the past five years, First Transit received multiple complaints from both the ATU local and rider advocates, who asserted that the company let buses fall into disrepair, fostered a bad working environment, was guilty of rampant mismanagement. These problems were further compounded, they claimed, by a repeated dismissal of these worsening issues and a lack of transparency from city staff. In late 2015 Council overruled one of its own committees and put First Transit’s contract back up for bid.

The fight played out across multiple years, two Blade investigations and multiple Councils while dividing both some current candidates and Council members. Council member Julie Mayfield, then a member of the multimodal commission and a candidate in the 2015 elections, voted to give First Transit another go late that year, while some incumbents (Manheimer, Wisler, Smith and Bothwell) decided after public pressure to reverse that decision and put the contract up for bid.

When its contract came back up in 2016 as staff recommended once again that First Transit get its contract renewed, future candidates Rich Lee and Kim Roney took sharply differing sides on the issue (Lee voted to pass on staff’s recommendation to renew the contract, Roney opposed that recommendation vocally). Just Economics, a non-profit that had worked with the city on its living wage policy, vocally criticized the conduct of First Transit and city staff. The transit union took a stronger public role than before, with drivers directly criticizing staff and the management company, claiming they were making their job riskier and damaging the bus system in the process. They even presented a no-confidence letter, signed by most of the system’s workers, to Council. Eventually, the city went back to the drawing board, claiming the process staff had used to consider the contract didn’t end up meeting federal law.

In the end, the critics won. The new bus system contract contained many of the clauses demanded by activists, including penalties for the company for missed routes or a failure to properly maintain vehicles, more oversight, new support vehicles and a customer complaint system. Also, unlike the 2016 process, this time rider and union representatives were involved in both drafting the contract and the criteria for assessing the bids.

Importantly, it didn’t keep the same company. As of October, Ft. Worth-based McDonald Transit will manage Asheville’s system.

The contract also cost more, with city staff claiming it would take $1.1 million more per year to guarantee things like buses running on time, in good repair and with greater accountability, bringing the total city cost of the transit system up to $6.7 million. Also, costs are predicted to escalate $200-400,000 a year through 2025.

Mayfield, who’s frequently advocated for more funds for the transit system, noted that these increased costs were just to keep the current system funding adequately, and asserted that they clearly showed the need for the city to commit to more reliable and better funding.

‘I have never seen this happen in Asheville’

On May 23, Luis Serapio was one of the first interpreters at a Council meeting, providing Spanish-language translation for a major public hearing. He also condemned Council for what he saw as a complacent attitude towards the needs of his community, “because City Council doesn’t do anything.”

On Sept. 12, Serapio was back in Council chambers, but for a very different purpose. This time, he was accepting a proclamation for Hispanic Heritage Month, thanking Council for “recognizing our contribution to the city and our presence.”

“I have never seen this happen in Asheville,” he said. “This means a lot, especially at this moment in our nation. One day I hope Juan, Sanchez or Lopez is up there with you.” Serapio recently started a Spanish-language tourism website, Descubre Asheville, focused on the city.

At least when it came to some of their emphasis from the dais, it appeared Council had shifted, just a bit.

Silence on the HB2’s ‘fake repeal’

On another key social justice issue, however, Council’s attitude was not change but silence. On Sept. 12 Brynn Estelle, one of the leaders of transgender support and advocacy group Tranzmission, came to the podium to call on Council to change course in fighting HB142, state legislation that largely preserved and reinforced the infamously discriminatory HB2. In an act of betrayal of the trans community and others threatened by the law, many Democrats backed the bill (the local delegation split) while Manheimer said in a public statement that she “applauded it.” While touted as a compromise, it left the law intact and was universally condemned by civil rights groups. Lambda Legal dubbed it a “fake repeal” and has filed suit to overturn it.

The act had echoes in Council’s refusal last year of a call by Tranzmission, Equality NC and the Campaign for Southern Equality — before the passage of HB2 — to pass a Charlotte-style non-discrimination ordinance. But City Attorney Robin Currin has espoused a far-right legal philosophy that cities have hardly any powers to fight discrimination. Last September CSE issued a white paper on the legal grounds Asheville could use to challenge the law and pass its own non-discrimination ordinance. The organization also offered a free legal team to aid in the effort. The city did not reply.

Earlier this year trans women, including Estelle, were repeatedly shut out of speaking a forum held by the Young Democrats and featuring local legislators who backed HB2.

Estelle pointed out that HB142 didn’t take place in a vacuum. Such laws were encouraged by anti-LGBT hate groups like the Family Research Council as part of a five-point plan to drive trans people from public life entirely and destroy any legal respect for their basic rights.

“This comes after a solid year of public vilification of our community at every level of the state, our harassers have never been so emboldened to discriminate against us and our town is apparently left with no recourse to address that situation,” Estelle said. “This is not abstract speculation, the realities of HB142 are being felt by those whose basic dignities it continues to render out of reach.”

“I don’t mean that the mayor had these scenarios in mind when she endorsed the legislation shortly after its passage, but I do hope that the actual human realities of that legislation can serve to move your hearts.”

“Currently our community watches as the administration checks off that five-point plan for eradicating trans people from public life bullet by bullet,” she continued. “We are hurting and the federal government will not help us, neither still will the state of North Carolina. So I ask you: will the city of Asheville stand with us?”

“Will you fight on our behalf, even if it gets messy, to do what you know is right?” Estelle emphasized. “I desperately want Asheville to live up to the progressive spirit it claims to embody, the Asheville people expect when they come hear to spend their money and their lives.”

Business owner Casey Campfield spoke in support of Estelle, asserting that “if we’re to establish ourselves as a city that is open to people of all walks of life we need to make a firm stand against bigoted laws like HB2 and HB142.

“Members of the city government have expressed concerns about a legal battle with the state, which most likely would ensue. But activist groups like the Campaign for Southern Equality have repeatedly offered to pay for legal expenses, so this argument doesn’t really hold water,” he continued. “I think this would be a strong message that you could send to your constituents, to the people of North Carolina, that Asheville is an open place that’s going to protect its citizens.”

That night Council was silent. But at a forum the next night held by the local chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America, Bothwell flippantly dismissed the push by trans activists to spur the city to fight HB142. Despite the previous white paper and offer of legal aid, Bothwell said the city should “pick our battles” and that he didn’t feel fighting the discriminatory legislation on behalf of Asheville’s trans residents was worth the attorney’s fees.

—

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by our readers. If you like what we do, donate directly to us on Patreon or make a one-time gift to support our work. Questions? Comments? Email us.