Will there be a city election next year? Will it use racist gerrymanders pushed by the state? Will City Hall fight back? What happens if they don’t? A look at the big questions looming over local politics.

Above: City Hall by night. Photo by Max Cooper

As the votes were tallied, victors declared and Ashevillians’ eyes turned to the aftermath of state and national results, there’s another question looming in the background, one that could reshape city politics.

Will the city of Asheville have an election next year?

City elections usually take place in the years between presidential elections and mid-terms. But a state law earlier this year backed by Republicans (and a turncoat Democrat) changed elections to even-numbered years and imposed an election system that splits up black voting power with gerrymandered districts.

Right now, even the people in charge of running local elections aren’t sure what’s going to happen in 2019.

“We shall see,” Buncombe County Elections Services Director Trena Parker Velez tells the Blade. “It’s a little up in the air right now.”

That’s an understatement. The state passing a law, especially about elections systems, doesn’t settle the matter. The GOP-dominated legislature loves gerrymanders at every election level, and courts frequently strike down, strike back or overrule them, often on the grounds that they’re designed to quash the black vote.

A court order could revert Asheville back to the same election system used since the early ’90s, even if a judge waited to make a final decision later. Under that “at-large” system, any city voter can vote for someone for every open seat, with the top vote-getters taking the spots. For example, last year all voters could cast their ballots for three Council candidates and one mayoral candidate.

Asheville’s aren’t the first local government elections the state legislature has tried to gerrymander. Both Wake County and Greensboro faced similar gerrymandering efforts, and both were thrown out in federal court. In both cases, court orders kept the new system from going into effect, meaning elections proceeded as they had before while the cases were being decided.

Indeed, by every indication Ashevillians overwhelmingly hate the system imposed by the state. When the question of district elections was put to Asheville voters in a 2017 referendum, they overwhelmingly rejected the idea, with 75 percent voting against.

Earlier this year, Council members condemned the gerrymander and the entire local state House delegation voted against it (the Senate, as we’ll see, was a different story). Given those circumstances and the level of public support for fighting against the gerrymander and the successful record of local governments in doing so, a legal battle seemed inevitable.

But since then things have been strangely silent. The city’s attorneys haven’t thundered to court, no judge has banged their gavel, no hearings have been scheduled. Legally, the districts and a year delay in city elections are still on the books.

So, what’s going on?

‘Not rushing anything’

Asheville’s gerrymander is a particularly strange one. In the other cases, local election systems overhauls were forced through by Republican legislators, with Democrats opposing them.

Not only were locals opposed to their election system being changed by fiat from Raleigh, the proposals promised to further enshrine bigotry. In response to Asheville’s appalling de facto segregation, black voters are beccoming increasingly organized, and neighborhoods such as Burton Street, Shiloh and Southside have seen increasing voter turnout in recent local elections.

After last year’s city elections, Council has the most African-American representation in decades. While spread geographically around different parts of the city, under the at-large system black voters could impact every Council race if they organized behind candidates and causes they felt represented their interests. State gerrymandering plans were clearly drawn to split up that vote and limit its impact on local elections.

This wasn’t the first time the idea had come up. Especially after the local right-wing’s electoral prospects were decisively wiped out in the 2015 primaries, they turned to the idea of the state legislature gerrymandering local elections to revive their fortunes. The next year Sen. Tom Apodaca, whose district includes a small slice of South Asheville, tried to ram through a draconian bill redistricting the city’s elections. In a political upset, the state House actually voted the proposal down.

In 2017 Apodaca’s successor, Sen. Chuck Edwards, proposed a bill directing the city to draw its own plan for a six district system. The bill contained criteria for those districts that would inevitably split up black votes and impose one of the most restrictive systems in the state (most local district election systems have a combination of at-large and district seats or require that some candidates come from certain districts but lets all local voters cast their ballots for every seat). The bill passed over Democratic opposition. Council pointedly refused to carry out Edwards’ directive, and put the plan to the voters of the city, who overwhelmingly rejected it, strengthening the city’s hand for a future court battle.

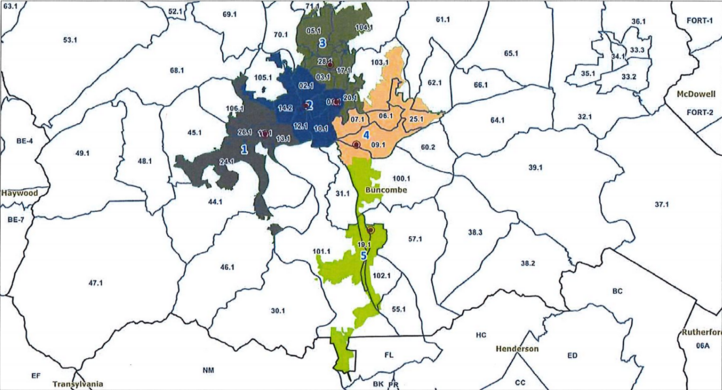

Gerrymandered Asheville election districts passed by the state legislature. The districts split up precincts where black candidates have done particularly well.

Edwards’ 2018 proposal has five districts, with one Council member and the mayor still elected at-large. But it pointedly still splits up the six precincts where black candidates have done particularly well into different districts, diluting their impact.

As the bill moved forward, it looked like the legislative fight would play out in a similar way as before: Edwards passes the bill with GOP votes, the Democrats oppose it, things proceed to the inevitable legal fight. The N.C. House, for its part, kept that pattern, with all the local Democratic representatives opposing the measure.

But in the Senate, something changed. Perpetual turncoat Sen. Terry Van Duyn, who’d earlier ditched the trans community by backing HB142, actually sided with the GOP’s racial gerrymander, supposedly in return for the bill agreeing to move city elections to even-numbered years, a change neither Ashevillians or their representatives had sought.

Nonetheless, despite Van Duyn’s treachery, city officials seemed adamant in their opposition. Council’s two African-American members Sheneika Smith and Keith Young, strongly condemned it, with Smith asserting it was “surgically drawn” to “dilute the black vote” and Young that “the African-American voting bloc will be completely wiped out.”

After the passage of the bill, Manheimer claimed the city was looking into its legal options, but told the Blade “we have pretty consistently opposed any plan to district the city…as far as I know that hasn’t changed.”

But there hasn’t been much since. To find out what was going on, the Blade called up all Asheville City Council members and the mayor.

“We have talked about it, but we postponed any decision until after the elections,” Council member Julie Mayfield said. She added that there was “some more research [now-departed City Attorney Robin Currin] wanted to do” but that the issue remained on Council’s radar and will probably “pick up when we get a new city attorney.”

That could take awhile. City attorney is one of three positions (along with manager and clerk) Council appoints directly. For comparison, former City manager Gary Jackson was fired in March, and city officials only announced the appointment of his replacement in late October. Currin’s appointment also wasn’t a swift process. Former City attorney Bob Oast retired in July 2013 and Currin didn’t take office until late March the following year.

Currin left in September, so if that history provides any clue to the timeline this time, the city probably won’t appoint a new attorney until next May at the earliest, meaning the question of even having an election would at least wait until election season’s normally in full swing (filing for city offices typically begins in July, and campaigning starts months earlier).

But Mayfield asserted that “we have time, we don’t really lose anything by waiting.”

Mayor Esther Manheimer, in an email to the Blade, took a somewhat more neutral tone than her comments this summer.

“Council has not yet decided what action it will take with regard to the districts bill,” she wrote. “We have received legal advice that we have a few different options and that we also have some time to decide so we’re not rushing anything.”

No other Council members replied.

Strange delay

What Mayfield and Manheimer are referring to is the fact that there’s no legal deadline for challenging a gerrymandered election system. If an organization can make the case, and has voters willing to say their rights are being infringed, they can challenge the state-imposed districts at any time.

As for how the recent elections impacting the outcome, longtime voting rights advocate Anita Earls won election to the state supreme court, giving Democrats a 5-2 majority. Some progressives have openly speculated that this could lead to striking gerrymanders down through that court, rather than a federal one. That’s not without precedent either. Pennsylvania’s state supreme court did just that, leading to a redrawing of congressional districts.

That said, the timing does matter. Elections don’t happen in a vacuum. By the winter before a local election year, potential Council candidates are usually already laying the groundwork for their runs. A shorter election season generally favors incumbents and more well-off candidates; more grassroots get-out-the-vote efforts take time to organize. On that front, the city’s “wait and see” approach has likely already had an impact on which candidates can run, or their odds if they do.

If the timeline ran late enough, it could even impact whether there’s an election at all, even if a city challenge did (like in previous cases) get a halt to the district system. North Carolina voters saw a particularly glaring case of this in September, when this year’s congressional elections went forward under a gerrymandered system because a judge ruled it was too late to stop the process.

Asheville also offers a strange contrast to both the Wake and Greensboro cases, where attorneys filed suit against the gerrymanders within days or weeks instead of waiting months.

While an interim city attorney no doubt makes things a bit more difficult, Currin was in office for months after the gerrymanders passed, and it’s not like city officials didn’t know Edwards’ plan was coming. Indeed, a letter from Currin to the state legislature after last year’s referendum, rejecting the state’s directive to change local elections, showed that the city attorney’s office has done extensive research on the matter.

Also, the city can hire lawyers; indeed, they’ve currently done so to fill in until a new city attorney is chosen. If Council wanted particular expertise in fighting these gerrymanders, the institutional clout and financial resources they wield as a local government would make partnering with a civil rights organization experienced in waging these battles fairly easy.

Then there’s the question of if the city will challenge the system at all. The step would be, to put it mildly, incredibly controversial, given the massive level of opposition Ashevillian voters have to this gerrymander and Council members’ own stated views. But city elected officials have stayed silent or neutral on the topic to a fairly surprising degree given their previous vocal commitments to fighting it. As Van Duyn flipping her vote shows, it’s not impossible for centrist Democrats to decide they’d be just fine with a racist gerrymander.

If that were to happen, it also might not be the end of the story. Just as there’s no timeline on local election system lawsuits, there’s also very little limitation on who can sue. Any civil rights organization that could muster the attorneys, the impacted voters and the facts to demonstrate how the district system disenfranchises locals could seek the same halt to the new elections the city would.

The gerrymander is the beast in the room of Asheville politics. If the state’s law were to go into effect, it would undercut growing black voting power, drastically limit locals’ say in their government and provide far more obstacles to movements for social change.

One of the most promising trends in recent years is an increasingly involved public taking an interest in local issues, making city votes more vital and competitive. But with “wait and see” from City Hall, Asheville’s very right to vote faces an uncertain future.

—

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by our readers. If you like what we do, donate directly to us on Patreon or make a one-time gift to support our work. Questions? Comments? Email us.