After tear gas, lies and excuses Asheville’s racist power structure loses a years-long battle, as the notorious monument finally comes down

Above: the removal of the top of the Vance monument last week. Photo by Orion Solstice.

In May 1898 the Vance monument was completed. Dedicated to one of the architects of Jim Crow, the stone obelisk was part of the propaganda for that year’s violent white supremacist campaign. Supported by the state’s elites, that effort overthrew the multiracial fusionist movement and culminated in the Wilmington massacre. It stood there for over a century as a reminder of segregationist power. This past summer, locals tagged “fuck this” on the hated chunk of rock. They knew what they were doing.

Last week that curse of generations finally started to lift. Not because officials graciously granted it but because last summer Asheville revolted and all the tear gas slathered over downtown failed to stop the people of this town. One of the many demands that emerged was — along with real reparations and seriously dismantling the police department — the demolition of the Vance.

Other liberal city governments, savvier oligarchs than their counterparts here, quickly conceded similar demands for the removal of racist monuments. But this is Asheville and if the local gentry can do nothing they will. So for months officials evaded, setting up commissions then repeatedly stalling, hoping the anger would dissipate.

Instead it only grew. By this spring council was regularly faced with the public cry of “if you don’t remove it we will.” With a dwindling police department and everyone from us millenial anarchists to civil rights veterans demanding its removal, city hall surrendered. Last Tuesday, May 18, workers began to remove the top of the monument, with the rest to follow in the weeks to come.

A mere five years ago it was a different story. Indeed, it looked like the monument would stay up for ever, with liberal city officials teaming up with neo-confederates to keep it in place.

What changed is another reminder that the greatest power in Asheville isn’t in city hall.

The gentry’s tower

If it were up to Mayor Esther Manheimer the Vance monument would have stayed up forever. She enthusiastically endorsed its renovation (no council member at the time voted against) in 2015. Her lawfirm, one of the most powerful in the city, contributed to the project. Later, as mayor during growing calls for its removal she would continue to keep it up. Last summer, after it was tagged (and her law office windows got busted), she declared a curfew and called in the national guard.

Zebulon Vance was, it bears repeating, a cold-blooded tyrant. Born into wealth and privilege, he spent the entirety of his years dedicated to upholding a segregationist regime and his corrupt power within it. His legacy is steeped in the blood of thousands, from the antebellum enslaved to locals who fought the confederacy to prisoners fed into a dangerous railroad project that gained him even more wealth.

While he occasionally clashed with other ends of the confederate regime during the civil war, it was the old story of fascist official feuding with other fascist factions. He was fully dedicated to the slave power and proposed, without an ounce of mercy, deporting the entire population of rebellious parts of WNC on a death march. His equally aristocratic brother, a regime commander, was cut down in an ambush by anti-confederate insurgents. It is a tragedy of history that Zebulon Vance didn’t meet the same fate.

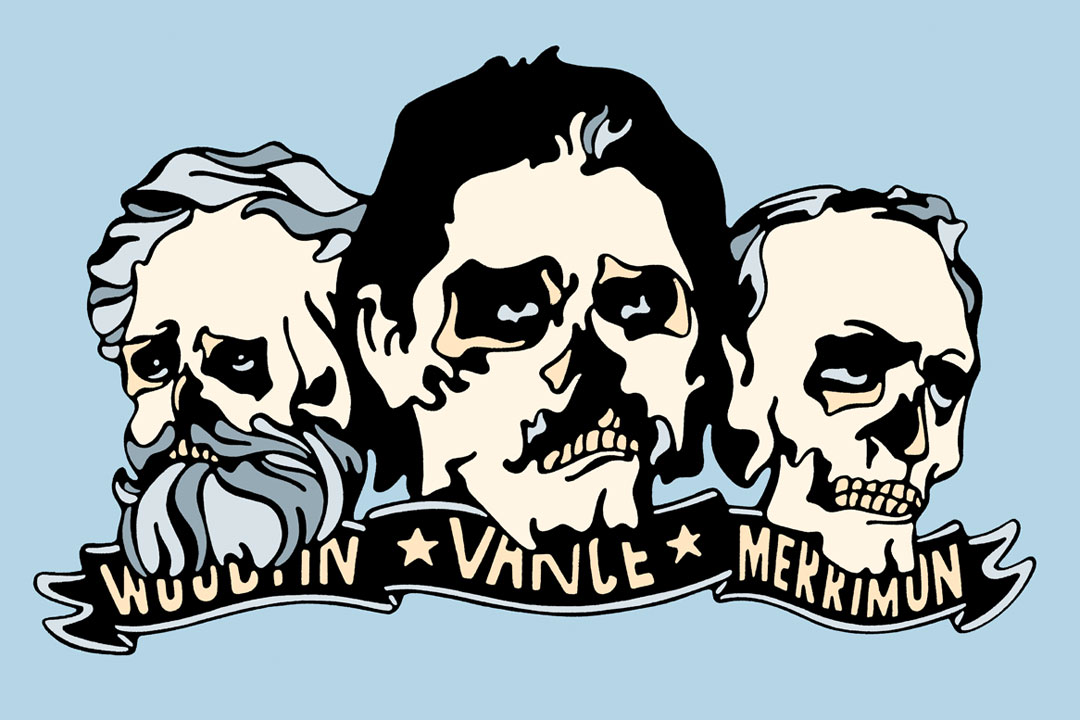

Art by Nathanael Roney, depicting Vance, Merrimon and Woodfin as the creatures of death and corruption they always were

The confederacy still lost, in no small part due to insurgencies and Black resistance throughout Appalachia. In the spring of 1865 Black locals triumphantly marched through town.

But after the war, with the help of equally evil peers/rivals like Augustus Merrimon, Vance and the aristocracy he represented clawed their way back to power with the help of the klan. The system of mass incarceration we deal with today was pioneered by those like Vance and Merrimon. He later worked thousands of prisoners, many to death, building a railroad he personally profited from.

Among Asheville’s white gentry, including the liberals, Vance was lauded until recently. Back in 2007 liberal darling (and later council member) Cecil Bothwell briefly joined a think tank named after Vance. Until 2011 the local Democratic Party held the Vance-Aycock dinner, named after him and Charles Aycock, one of the white supremacists behind the Wilmington massacre.

The 2015 renovation of the monument, a partnership between the city and a neo-confederate re-enactment group, faced no serious opposition on the all-white council.

Later that year, at the inauguration of the new council Manheimer passed out lyrics for a new Asheville anthem, which blithely noted the monument’s role in slavery. Her father led a sing-along In a particularly servile display, most of the media joined in. One later said that they were afraid that if they didn’t they would get scolded. Only the Blade contingent — myself and photographer Max Cooper — refused.

Tumbling down

Fortunately plenty in the city were made of sterner stuff than racist officials and lickspittle press and a broad movement to take down the monument continued to grow.

In 2017, just after the far-right violence in Charlottesville, a multiracial crew of Ashevillians tried to pry off the Robert E. Lee highway plaque in front of the Vance monument. They were arrested. As council vaguely expressed concern, local Nicole Townsend told them that “good intentions and liberalism are both modern-day nooses” and council needed to “be on the right side of history and stop having conversations about it.”

Protests, when they had to note the vance as a landmark, just started calling it “the racist phallus.”

Less than a month after the attempt to remove the plaque, confederate flag-toting fascists attempted to rally at the monument. They failed because a wide mobilization of anti-racist locals took the space first and refused to let them advance.

The monument’s supporters, as an in-depth piece on Vance’s history noted then, were asserting a weird contradiction: on the one hand it was such ancient history that it should just be left be. On the other, that it was so important that those trying to remove it should be arrested and attacked.

The fact was throughout its century-long existence the monument remained a symbol of the city’s racist power structure, one reason why the town’s white gentry have always defended it. The conservatives with racist flags and guns, the liberals did so with their usual method of handwringing while quietly calling the cops.

They forgot about the rest of us. The ranks of those wanting the monument gone continued to grow. A movement to recover Asheville’s Black history and debunk racist myths brought more attention Vance’s atrocities and their role in today’s racist status quo. Protests and demonstrations repeatedly targeted it. Demands for removing the monument joined those for defunding the police. Even Vance’s own descendants called for the monument’s removal

The Vance became a focal point in last summer’s uprising. Manheimer and the far-right defended it, both in different ways. The cops with threats and tear gas, the far-right by sending literal armed klansmen to confront anti-racist protesters (the cops hob-nobbed with them, naturally).

Instead of just outright removing the monument, Manheimer and her allies on council sought to keep running out the clock. They appointed a commission to look into the matter.

In October, commission members and council candidates close to city hall briefly floated a proposal, with the tacit backing of staff, to “repurpose” the monument, including sides painted red and yellow for different races and ethnicities. Somehow this made it even more racist. Fortunately it was met with intense backlash.

In the end the whole committee (except for local attorney Ben Scales) voted to demolish it. So did the county commissioners and most of council. Even Manheimer and then-vice mayor Gwen Wisler, who had voted to renovate the monument five years before, now seemed to support its end.

But as late as this January Manheimer and city manager Debra Campbell were still trying to keep the monument intact. Campbell told the Council of Independent Business Owners, a far-right group, that they might not remove it at all.

This last-minute evasion failed. Council’s public comment periods were taken over by locals telling council that if city hall didn’t remove it, they would.

On March 23, suitably shaken, council voted 6-1 (conservative Sandra Kilgore was the sole “no” vote) for the monument’s removal. Last Tuesday, May 18, it started coming apart piece by piece.

So good riddance. This is a real victory and it’s worth celebrating. Against all odds the Vance will fall. May it be ground into dust along with everything it embodied.

But Vance’s biggest monument is the jail. The confederacy is still alive every time a cop terrorizes a Black neighborhood. Until those are gone their evil is still with us.

—

Blade editor David Forbes has been a journalist in Asheville for over 15 years. She writes about history, life and, of course, fighting city hall. They live in downtown, where they drink too much tea and scheme for anarchy.

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by our readers. If you like what we do, donate directly to us on Patreon or make a one-time gift to support our work. Questions? Comments? Email us.