A multiracial community coalition mobilized to save Asheville Primary School. The central office and city hall insisted on destroying it anyway

Above: Mural on the side of Asheville Primary School. Photo by Matilda Bliss

“A school is a home. So when they come for your schools, they’re coming for you. And after you’re gone, they’d prefer you be forgotten.”

– Eve Ewing, Ghosts in the Schoolyard: Racism and School Closings on Chicago’s South Side

On June 7 the staff of Asheville Primary School sent the last students home, closed the doors at 441 Haywood Road and departed. They left a building that watched quietly while generations of children learned to read, write and forge their own paths.When classes resumed across the district on Aug. 29, for the first time since color television hit the department store shelves, there would be no first day of school at 441 Haywood. Rooms full of maintenance equipment took the place of students.

But Asheville Primary wasn’t a casualty of some tragedy beyond anyone’s control. Its destruction was deliberate. Cabals of central office directors, non-profit complex hacks and their cronies pushed, hard, in the face of widespread community opposition to shut down a thriving school with an innovative educational program.

The school lay smack dab in the middle of a neighborhood hit repeatedly by interstate projects, urban renewal, racist cops and gentrification. But its detractors claimed, ludicrously, that Asheville Primary’s multiracial coalition of parents, teachers, and students were the ones failing the city’s Black children.

Indeed the same powers that be — an un-elected school board, corrupt administrators and city hall — behind Asheville City Schools’ plummeting enrollment and astounding racial disparities would repeatedly blame a single primary school for their own failings.

Asheville Primary was the first. Unless something changes it will not be the last.

Under the radar

“If the building has to shut, the program continues, Ms. Tima is still the principal, Ms. Susannah is still the principal, the teachers are still the teachers, and we find the capacity to build the community within another facility. So that’s what I’m obligating myself to to you, that we’re not going to end the program. That we’re going to continue for those kids in it and possibly expand it.”

— Superintendent Gene Freeman discussing Asheville Primary’s Montessori program during a Nov. 10, 2020 presentation. He would later end the program.

“We’d love to continue the dialogue, if there’s like creative problem solving that needs to happen for locations and how that works out. I know that as a parent, we’re all really committed to making things work and being flexible, and so we’d love to continue being part of that conversation.”

– APS parent Lara Lustig during the November 2020 “town hall”

The destruction of Asheville Primary School began blandly, with staff armed with business terms questioning the state of the building in a series of “town halls” in the fall of 2020.

In retrospect there were some warning signs that the central office wanted to keep this eerily under the radar. Around the same time their social media account repeatedly advertised a series of town halls about attaching a new name to the former Vance Elementary. But the district completely evaded mention of a “town hall” around the fate of Asheville Primary. Even the school’s own Facebook page just posted non-descript zoom links to two of “town halls.” They failed to mention a third meeting entirely.

The district had neglected the school, sitting close to historically Black Burton Street and the massive Pisgah View public housing complex, for decades. Asheville City Schools had spent less than $500,000 on repairs to the building since 2017 painting a mural, building a playground and repaving the parking lot. The district had begun addressing a mold issue (created by their own neglect). In October of that year during town hall presentations, staff discussed repairs in the millions of dollars. Known about since “a couple of years ago” but not discussed at meetings, those repairs supposedly totaled “over $6 million,” but that could be paid for over several years time.

In 2017 then-superintendent Pamela Baldwin claimed the central office would seek funding for improvements to the building, but neither Baldwin — nor the three other superintendents that would quickly follow her — would address the building’s core issues. They also did nothing to prepare it for the looming I-26 expansion. According to district administrators, who talked in business jargon instead of lives and education, this was because the school’s population was smaller than others and would thus be a lower “return on investment.”

At stake were seven preschool classrooms designated “five-star” by state licensors because of their access to numerous staff, plentiful square footage, direct exits to the outside, and age appropriate bathrooms. The designation acknowledges the highest quality childcare, giving the program secure standing when it comes to accessing thousands of dollars per pupil in state-provided preschool development grants during city schools’ mostly self-inflicted budget crisis. The school was also the site of an innovative and widely-praised Montessori program.

Quality preschool has an even greater reputation than Montessori for helping to close racial achievement gaps, and Buncombe County government further rewards such programs through its Early Childhood Education Grant program, filling in where state funding leaves off in an attempt to make preschool more accessible.

The Montessori education model was created by Marie Montessori in the early 20th century while she worked with disabled and neurodivergent children. She emphasized a model with mixed-aged classrooms, a broader range of activities, collaborative learning, and uninterrupted blocks of work time. The Montessori system has, from its creation, better included neurodivergent and disabled children in the classroom and has even been shown to reduce racial disparities.

In Students of Color and Public Montessori Schools: A Review of the Literature, Mira C. Debs and Katie E. Brown explained, “A recent study found that Black third graders in a public Montessori magnet school outperformed their traditional school counterparts in both reading and math. When compared to other magnet students in the same district, these Black Montessori students still performed better in reading and equally in math.”

While standard testing criteria have a bevy of problems, even they note that in many cases Montessori students have gone on to outperform peers in high school and college.

Though the authors reiterated the need for studies to more often delineate by race, their findings point to the strong potential for Montessori classrooms to support Black students in ways traditional classrooms have failed them time and again.

If the Montessori program was used for long enough and was given the tools that it needed, the program could have been another tangible asset for the district looking to address the racial education gaps its system had helped to create and for a city and county supposedly concerned about reparations. Even superintendent Gene Freeman, who presided over APS’ destruction, initially claimed he wanted to study the possible benefits of Montessori.

Given time (and expanded enrollment) APS could have very well shown its value as graduates of the program made their way through middle and high school. Sure, there were costs associated with an aging building and a relatively smaller student population, but these costs would certainly have been cheaper than the December of 2021 quoted $40 million minimum price tag had another building of its kind been constructed in its place.

Parents, teachers, and students were misled from the beginning of these conversations about issues that could have been addressed years prior. But at the behest of the superintendent, it took not even a month for questions to suddenly swirl in district board meetings around whether or not to sell the building that housed Asheville Primary, an option proposed not once during consecutive “town halls.” They started with lies. The harassment towards those who loved this school would follow.

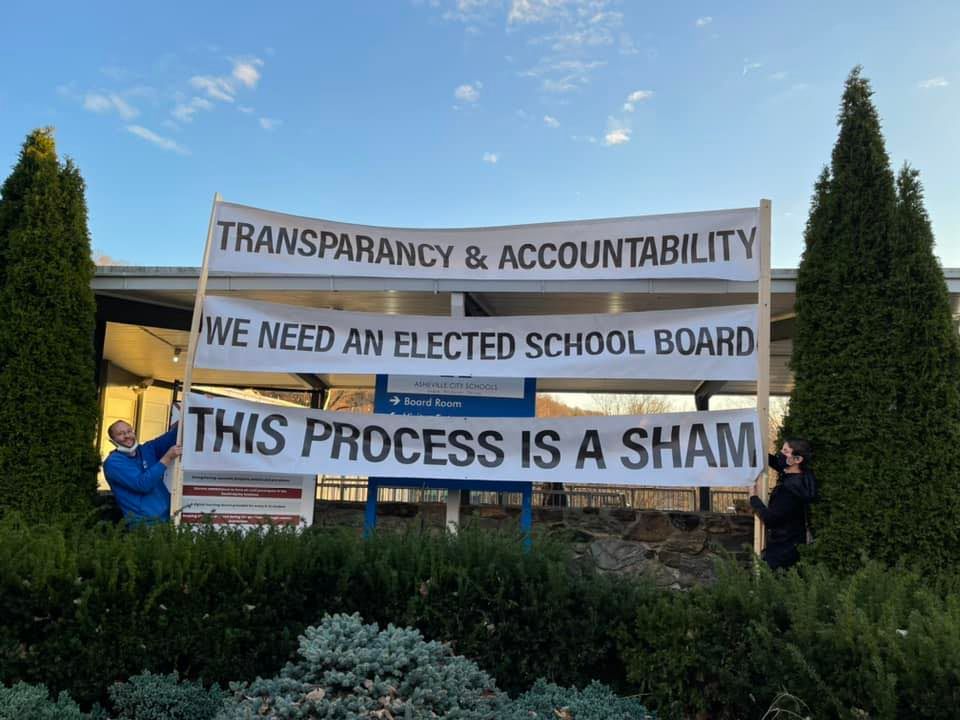

‘This process is a sham’

“Back to segregation. We would all like our children to be happy around, I guess their kind. It’s a different age, though. We can’t go backwards. We stood out there, a few of us stood out there last year in front of that Vance monument that just took it. I was one that got shot in the face by that smoke bomb, whatever. But now it’s coming down. That means change. We don’t have to do that to the children. It’s like don’t talk about it, be about it. If you say you care about these kids, do it for them. Don’t do it for you, don’t do it for another hotel coming up in Asheville. My opinion, I think the ulterior motive is they want to put another hotel there.”

— Idris Salaan, former volunteer at Asheville Primary School during the May 24, 2021 school board meeting

Parents and educators initially met the central office’s concerns with a collaborative spirit, trusting that the school board would address the issues facing Asheville Primary instead of closing it in the middle of a pandemic.

But then, in December of 2020, Freeman suddenly proposed moving all of the Montessori students at Asheville Primary to Hall Fletcher and the preschoolers to other sites, claimed that repairs could cost $9 million instead of $6 million and proposed enrollment in Montessori be limited to siblings, all without a public hearing. The school board then voted unanimously to follow through on his recommendations and study the closure of Asheville primary.

Shocked and dismayed locals began organizing in earnest to save the school. A petition would go up within days, and one advocate created a Facebook event to draw attention to the superintendent’s blatant disregard for open meetings.

“Why are the Board and Gene Freeman acting as if public understanding and input is their enemy?” asked school volunteer Gabrielle White.

Parents and other concerned locals would flood social media, starting the Save Asheville Primary School group and page, where a community could vent and exchange information and meeting details and calls to action could be shared. This would soon become a multiracial, multigenerational movement that would bring the issue wide public attention and take meetings by storm. A few, namely Acebo and educator Libby Kyles, would even apply to join the school board. Over 3,000 locals would sign a petition to save the school.

In response superintendent Freeman and the system’s establishment would react with anger and contempt, even breaking open meetings laws to push through the destruction of a children’s school.

Supporters of Asheville Primary hold a banner outside a 2021 school board meeting. The central office repeatedly broke open meetings and records laws to push closing the school. Special to the Blade

This wasn’t entirely surprising, given his record. Freeman left his previous superintendent job in Fox Chapel, Pennsylvania in disgrace, embroiled in various scandals that included endorsing his realtor for reelection to the school board and threatening journalists for questioning the obvious conflict of interest. The scandals also included Freeman sending cease and desist orders to half a dozen parents in retaliation for speaking up on social media about his administration’s lack of transparency. Before Fox Chapel, while he was superintendent of Pennsylvania’s Manheim Township’s schools, he had stripped physical education, art, and music classrooms from schools. The school board, appointed by city council, apparently thought he was perfect for Asheville.

In February Freeman lashed out at the growing movement to save Asheville Primary by stating that policy should not be “guided by groups of 50 people who want certain things.” He’d later blame “acquiescing to demands” for the central office’s own incompetence in mismanaging their own budget. At the same time the office included more administrators than the Buncombe County school system — four times its size — raking in over $70,000 a year. Some of these positions are so unusual that the state refuses to fund them.

Locals across the political spectrum spoke out against the closure and campaign of spying and retaliation waged against teachers who opposed the closure.

“I know that our teachers are being called in to central office for thumbs up on Facebook and having the first amendment right being challenged,” non-profit fundraiser Honor Moor said. “There are people who left [a district parent group] because of fear, because we have moles in our group who are reporting to central offices.”

Meanwhile, led by Housing Authority resident services coordinator Shaunda Sandford, who was also the school board chair, the district fumbled an opportunity to fund its preschool classes. At Sandford’s urging it chose to make its annual application to the county’s Early Childhood Education Grant Committee a poorly-thought out plan to push preschool classes out of Asheville Primary and other community locations and into Housing Authority properties at a cost of nearly $3 million over three years. Despite this massive conflict of interest — she’d proposed to close Asheville Primary in a way that would get her employer a substantial amount of money — Sandford would continue to vote on the school’s fate. Not shockingly she pushed to shutter it.

County government would reject the application. Costs aside it would have, with very little notice to affected programs, evicted preschool classes into a bureaucratic mess. In addition to the impact on APS, for example, the proposal would have evicted Community Action Opportunities’ Head Start classroom from Southside’s Lonnie D Burton center. That program would have needed to move this class into another county, meaning a net loss of preschool classrooms for Buncombe. Bluntly Asheville City Schools failed to get preschool grants due to its own massive blunder.

Even with central office incompetence costing the system much-needed funds there were options to keep beloved schools such as Asheville Primary open. They include using part of the millions in cash reserves that are part of the $406 million county government’s budget or the tens of millions in cash reserves that are part of the $217 million Asheville government’s budget. The Dogwood Trust exists solely to fund projects such as the repairs the school needed.

Hell the sheriff’s office has received an additional $7 million on top of their combined $38 million budget since July of 2020 to kidnap locals and operate the deadliest jail in the state. Asheville police now receive over $30 million and receive shiny new stations whenever they want. Though much is made of the amount of funding dollars per student at Asheville City Schools, according to a 2020 study, Buncombe government is 84th in the state when it comes to their relative effort, a funding calculation that compares their revenue vs its spending per pupil. If the district (and local government) truly wanted to keep Asheville Primary open, they had plenty of cash to do so.

The district could have addressed its hyper-strict enrollment policies that had been draining its general fund since 2017 and maintaining racial disparities for years by favoring white gentry. Less students after all means fewer dollars.

The general assembly gave the district permission to return children to schools in March, and Asheville Primary students were allowed to return to their building. But what was going to be a March vote on the closure of the school became a May 24 vote. Meanwhile it became clear that the building at 441 Haywood Rd. would not be sold anytime soon. Officials had finally realized that in accordance with the state’s Article 39 law governing the sale of school buildings, this would do nothing to revamp the cash reserves available for the district.

“When you’re the parent of a kid with social, emotional, and learning differences, you expect to tolerate their school, not love it, and I went in with a guarded heart. But every person I have encountered there has been nothing short of amazing,” Brittany Wager, whose children had gone to the school, said at the May 24 meeting.

Wager followed with a grim reality:

“The educators at Asheville Primary have been second to none. There was Ms Stephanie in Kindergarten who knew exactly when to push Rowan and when to pull back and let him discover things on his own, so that he didn’t get overwhelmed. She now lives in California. There was Ms. Nicole in first grade who recognized his need for additional support with reading and gave him extra help every day. She now works as a private tutor. And this year’s teacher Mrs. Leslie, who I have never had the pleasure of meeting in person, who has fostered an atmosphere that feels safe and nurturing for both virtual and in person kids. With her, Rowan is having his best year yet.”

“Through our years of being there, my daughter, she has excelled – more than I did when I was in traditional school,” Pisgah View resident Taysia Elliott said during the same hearing. “There’s so much to be learned in the process of sending our kids of color, Black, Brown…seeing what they get out of it, and compare that system of learning with traditional school.”

“They feel like they’re at home,” volunteer Idris Salaan noted. “I have four grandchildren that went there, and they’re excelling, and I’m not just saying that. I’ve got a niece right there, she’s doing the same thing. I mean, come on, the money’s there and why we trying to break up a happy family.”

“We all know that the education system as it is, isn’t designed for people of color,” Michael Woods said, in support of saving Asheville primary. “There’s a cost, but low income kids have been paying this cost.”

“I’m nine years old and in third grade. I love my school. It’s very special to me, and if you move it, it won’t be as special anymore. I like it just the way it is,” Iya Rose Senzon, one of many students who would speak out in defense of their school, said.

That time the pressure worked. By a 4-1 vote (with only Sandford voting ‘no’) the school board reversed course and decided to keep APS open. Not only would it stay open, but according to the board it would finally expand to 4th grade – two and a half years after this step was first proposed in 2018. Supposedly the school would expand to 5th grade in the ‘22 – ‘23 school year, but also promised to “revisit the location” of APS in December ‘21.

These assurances would not last. Asheville’s public schools, like so much of the city itself, are forged in broken promises.

The neighborhood and the interstate

“Historically the intentional disruption of the African American family has been a primary tool of white supremacy, one with deep roots extending from the time of chattel slavery through the present era of mass incarceration.”

— Eve Ewing, from Ghosts in the Schoolyard

In order to fully understand why officials were so ferociously intent on destroying Asheville Primary School, we must go back to 1953, the year that Aycock Elementary School opened at 441 Haywood Road.

Viola Knollman’s sunken gardens laid across the street from the school and catty-corner from B&B Pharmacy. The working class white East-West Asheville laid to the east and Burton Street to the west. Aycock was a segregated white school then at the border of two neighborhoods. Black children in the area attended the Burton Street school.

This was before urban renewal, before the interstate.

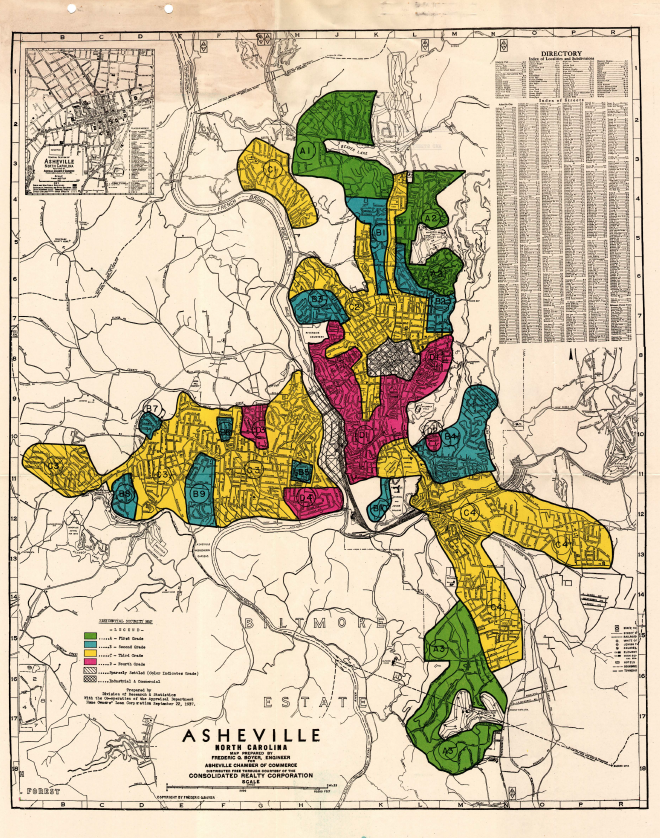

Both absolutely devastated the tight-knit Burton Street neighborhood. The famed sunken gardens were uprooted. Entire blocks were bulldozed and schools shut down to make way for the interstate and a lopsided version of desegregation that centered white students and the white educational establishment. If they had to integrate, white officials decided, they would do so in a way that punished Black communities as much as possible. These policies, hand in hand with redlining, shut down a school and spelled widespread disaster for vital informal educational networks.

The 1937 HOLC map of Asheville. All but one of the areas marked in red are majority African-American. Redlining would shape the interstates that devastated the Burton Street community and furthered segregation. Image via Mapping Inequality

With the 1966 closure of Burton Street School, many Black students were redirected to Aycock Elementary. But now an interstate separated it from that community.

East End resident Johnnie Grant noted that Asheville’s desegregation plans “never demanded that white students step outside of their comfort zone. Black schools closed, black students were bused, black teachers and administrators lost their jobs, but whites continued as before.”

It was in this environment that Black children were asked to learn.

The Asheville Primary site is part of census tract 10, historically a working class neighborhood. West Asheville in fact was once mocked as “worst Asheville” mostly by outsiders unwilling to tolerate the neighborhood’s initial resistance to gentrification. As Black residents were forced out by urban renewal, many were directed with lofty promises to the Pisgah View public housing development.

Despite gentrification, as recently as the 2010 the census tract was 18.1 percent Black.

Waves of gentrification and concentrated police violence struck the neighborhood in the decades that followed. Jerry “Jai” Williams was initially targeted in Pisgah View before he was killed in Deaverview by Asheville police Sgt. Tyler Radford in the summer of 2016.

Gentrification took a less obvious, but still devastating, toll. According to census data between 2010 and 2020 the tract had lost 245 Black locals, mostly youth, a loss of Black locals second only to the Southside neighborhood. During the same time the white population in the neighborhood grew by over 500 residents.

As if all that wasn’t enough, the wildly unpopular I-26 expansion project still looms like the sword of Damocles, threatening Burton Street once again. The project, backed ferociously by the chamber of commerce and other gentry groups, was used as an excuse to starve Asheville Primary School of funding (and enrollment) as early as 2018. As 2021 wound on it was invoked as an excuse to close the school for good.

Just before closure, 41 percent of the school’s students depended on free and reduced lunch, a mark of an impoverished student population that year after year, out of the district’s six elementary schools placed the school in the bottom three of schools with student populations dependent on the program. It should come as no surprise that the neighboring Hall Fletcher Elementary, recently faced with its own share of heavy handed treatment by the district, has always been right there with Asheville Primary supporting disproportionately impoverished students.

Asheville Primary School was less than three miles from Maple Crest, Livingston, Hillcrest, and Deaverview public housing. It was less than a mile from Pisgah View, the closest of any city school. Unlike several of the district’s elementary schools, city buses served the front door of 441 Haywood, increasing its accessibility to impoverished and Disabled students.

Urban renewal dealt a devastating blow to the economic power of Black residents not just in the Burton Street neighborhood but throughout the city. Gentrification and police violence followed up to ensure de facto segregation. The attack on Asheville Primary was also an attack on Asheville’s Black communities. Similar tactics have been used in cities like Chicago, where massive school closures are widely considered a weapon of gentrification. As accessible services are stripped from Black families, school closures push residents out of school district boundaries and out of the city.

Due to this city schools as a whole have grown whiter and whiter as fewer and fewer Black residents can afford to live in a district that includes less than half of the city’s population. Any programs that can actually address this injustice seem to get defanged or destroyed as soon as possible.

Finger on the scale

“Reparations include education.”

— Dewana Little during the Feb. 23, 2021 city council meeting

“It matters not if the glass ceiling is broken if this council continues to work with the status quo of backdoor meetings and decisions being made based on what is now the ‘good ole girl’ network vs making decisions based on what is best for our community and in the case of the school board, what is best for our children.”

— Libby Kyles during the March 9, 2021 city council meeting.

Unfortunately the school board and central office had plenty of help furthering their disastrous agenda, and as the fight over Asheville Primary widened in 2021 city council decided to give them a major assist.

In January of that year city government had issued a public call for applications to join the school board, in what was widely considered its final set of appointments before it finally moved to an elected school board. Libby Kyles, Pepi Acebo and Jackie McHargue would apply with the endorsement of the Asheville City Association of Educators (ACAE), the local teachers’ association. Dozens of locals would speak out in support of these candidates during council meetings.

Though city council refused to directly address the future of Asheville Primary School, ACAE did. In her application for the ACAE endorsement, Libby Kyles, a Black educator who’s repeatedly spoken up about the city’s de facto segregation, rejected the proposal to close Asheville Primary School.

“It seems incredibly short sighted in it’s approach to addressing financial woes that exist because of the yes board mentality and the mismanagement of funds.”

Kyles followed, “you are not going to close the achievement gap by farming out all preschool classes to public housing.”

Acebo would state in his application: “There are so many equity-specific advantages to Montessori, including the standard practice of providing an individualized educational plan for every student by default and building peer leadership skills in every classroom through multi-age experiences and self-assessment.”

If schools were to be temporarily combined, he pushed for those conversations to happen between the schools most impacted, and “not because the new superintendent who doesn’t understand our schools and programs thinks he has found a get-out-of-jail-free card by selling the building.”

Asheville city council refused to interview either of them. The conversation would then reach a boiling point during the Feb. 23, 2021 council meeting.

“Our Black kids matter. You had all these protests this summer. Our Black kids matter,” Dewana Little said, pushing back against city council’s determination to ignore two of the three ACAE endorsed school board candidates and many others who applied.

During their March 9, 2021 meeting council’s conduct, part of a pattern of ignoring and actively suppressing the voices of Black locals trying to participate in their meetings, provoked Kyles’ ire.

“The many conflicts of interest that exist with our current board are astounding. And the fact that we are at a point where half the candidates, more than half the candidates for school board appointments are being ignored is irresponsible,” she said.

City council refused to listen during either meeting. In March they chose Peyton O’Connor and McHargue to fill two of the empty positions and allowed current board chair James Carter to retain his seat.

Then on Aug. 24 city council went into cloak and dagger territory, rushing to approve school board candidate George Sieburg to replace resigning member Jackie McHargue.

They added this item to the agenda hours before the meeting, after the deadline for signing up for public comment had passed. This gave locals no time to speak on — or even be aware of — the issue, violating open meetings law.

ACAE followed with a statement: “We were dismayed to discover that the committee recommends skipping any application and vetting process in favor of making a direct endorsement.”

“We do not take the importance of this role lightly,” the group said.

Importantly, George Sieburg supported the closure of Asheville Primary, stating in an unsuccessful application for ACAE endorsement that “I support the sale or a different use that does not include student classrooms in that building.”

Sieburg was thoroughly a non-profit complex hack. He was the former finance director of Homeward Bound, well known for selling out houseless locals to help supply their executives with lucrative salaries. He was also the former board president of Asheville City Schools Foundation, a large non-profit closely tied to city government and major corporations like Duke Energy and Raytheon. He replaced vocal APS advocate McHargue, who had announced plans to move to Weaverville in three months. While normal city practice is to let a board member finish out their term even if they move, Asheville’s council moved quickly to select Sieburg by a 6-1 vote, with only council member Kim Roney dissenting.

“We did extensive research individually on the candidates that we chose,” Vice Mayor Sheneika Smith, who’s well-ensconced in the non-profit complex, said. She claimed his selection required no additional hearing or public comment.

Councilwoman Antanette Mosley, a corporate attorney, praised Sieburg: “I think he would be a huge asset.”

Sadly this last minute bureaucratic coup d’etat would seal the fate of Asheville Primary.

Who segregated the schools?

“You have a small group of parents or a small number of people in the community that are causing everyone to go stress out, and it’s unfair to our principals and staff, and our other students. We’re spending too much time, as George stated. You either keep it or we’re going to close it. I mean you’re talking about one school with a very small number of students. If we absorb the students, we have our preschool program right there. And you can put the preschool program into the other schools, because y’all have space for the preschool classrooms, as opposed to trying to make this Montessori work.”

— School board member Shaunda Sandford-Jackson during the Dec. 6, 2021 schoolboard meeting.

“It has always been known that following one’s own sweet will does not of necessity bring either the most of knowledge or the best of conduct. It is, indeed, the insistent obtrusion of this easily observed fact that has led parents and teachers in all times to set such severe limitations upon the free expression of the child’s spontaneous impulses.”

— William Heard Kilpatrick, education establishment figure, Montessori opponent and staunch segregationist

The Asheville city school board is hardly the first institution to scoff at Montessori. The first wave of international interest in Montessori in the early 1900’s was upended by the us educational establishment that was terrified of the potential threat to dominant american systems posed by the possibility of generations of independent thinkers.

It wasn’t until the 1960s, decades after conventional (and compulsory) schooling had become an overwhelming feature of us society, that Montessori programs began to take root here. Some even started in Asheville in the 1980s. But before 2017 charter schools, often inaccessible to low income families, were the only option for Montessori within the city. It took more than 100 years for Montessori education to arrive in Asheville City Schools, in part a response to locals’ demand for alternatives to conventional schooling.

In the Fall of 2021, following council’s coup, word began to circulate that Asheville Primary was back on the chopping block. “Surveys” were conducted, and the hand-wringing by the city schools central office commenced. On Dec. 6 the school board listened to various school principals discuss the space their respective schools had for housing APS students. Adding walls to subdivide rooms was brought up, and so were modular classrooms in fields. Six months after promising to revisit the location of the preschool and Montessori school, staff half-assed a relocation plan that was obviously meant to lay the groundwork for closure.

Ludicrously, it also meant well-paid administrators and non-profit hacks loudly asserting that Asheville Primary was too small and too white to keep open, and that the multiracial coalition defending their school were the real racists. Yes, really.

“We’re also at a crossroads, of what Shaunda said, of an equity crisis,” Sieburg, who is well-off and white, said in support of Sandford’s insistence on destroying Asheville Primary School. “We’re at a crossroads. So we’re at a crisis of finance and equity, and in my experience, it doesn’t make sense to operate a school that way.”

“We have bigger issues than Montessori [laughs] and Asheville Primary,” he followed.

The claim was blatantly false. After their push to close the school was defeated the district finally reopened Asheville primary’s enrollment, but for only two weeks in June. The constant attacks on the school meant parents were understandably wary of sending their kids there, further hindering enrollment, which dropped so far, in fact, that principal Tima Williams could no longer be paid using state funds.

Despite that Black students still made up 13 percent of Asheville Primary School’s student body in its final year, higher than the Black population of Asheville and only slightly below the district average of 16 percent. Black enrollment had decreased since the school’s inception, but this was frequently due to policies dictated by the same institutions that wanted to close it.

It was the old tactic often used to destroy public education: cut its hamstrings and then loudly proclaim that it can’t run a race.

Black families are disproportionately ejected from the Asheville City Schools district, often due to stringent admissions criteria set by the school board and central office. Asheville Primary’s Black students suffered badly from this.

The district itself is an area that encompasses less than half of the population living within the Asheville city limits. As gentrification intensifies, living in-district thus becomes even more expensive and for numerous reasons even more difficult while Black in “the worst place to live.”

The neighborhood itself has faced some of the worst gentrification in the city. According to a study by Buncombe government’s Ad Hoc Reappraisal Committee, home prices are up 51.2 percent in West Asheville since 2016, a nearly 25 percent larger increase in costs compared to the rest of Buncombe County. As the stilted mcmansions go up and the airbnbs steal existing rentals Black families leave in droves – unable to afford housing partly due to the county’s racist property taxes, which wildly inflate values in Black neighborhoods while undervaluing them in well-off white areas.

Once a family has been forced to leave the city schools district itself, Asheville City Schools criteria — written to favor the gentry — make it very hard to stay in. For their child to be allowed to attend out-of-district families must pay $300 every year, plus a $50 application fee to Asheville City Schools, plus $100 for each additional student, plus $50 to release the child/children from the Buncombe County School district.

The Asheville district also refuses to provide transportation to out-of-district students, creating yet another barrier. The enrollment of out-of-district students can be revoked to make room for in-district students every year, meaning a wealthy transplant whose family can afford to purchase property near city schools can kick out a working class student whose parents can barely afford the district’s fees.

Checks and applications must be delivered to the respective offices in full by the enrollment date every May. Out of district disabled children, or children needing an individual education program (IEP), may be denied enrollment in Asheville City Schools if staffing is not available. Remember this is during a staffing shortage. After all this the district demands that all out of district enrollment be approved only at their discretion, in a city school district notorious for its racist achievement and discipline gaps.

If by “discretionary enrollment,” you imagined the district meant all of the out-of-district students who can’t keep up with grades and discipline standards — which disproportionately work against Black students — would be removed from its schools, you would be correct.

The rules pushing out Black families and students were enacted fairly recently, hand in hand with skyrocketing gentrification.

“A plan to conduct an overall [sic] of the enrollment process was shared with the Board,” read minutes from the December 7, 2015 school board meeting without going into further detail. That year, citing a projected enrollment of 5,000 students by 2020 the district, supposedly fearing outgrowing its middle school, would move to sharply restrict enrollment in ways that favored the well-off. Not shockingly Black students, according to Fall 2021 numbers, are sharply underrepresented among out-of-district students in city schools.

Since then enrollment has plummeted. This also blew a hole in the system’s budget. Asheville City Schools reserves shrank from $6 million in 2017 down to around $1 million while APS was threatened with closure. Teacher and staff pay has shrunk when compared to inflation.

But the district has refused to push crucial negotiations with county and state officials to expand its boundaries to more resemble Asheville’s population, continuing to exclude many predominantly Black communities. The Shiloh community in South Asheville, for example, is inside the city limits but lies just outside of the school district. Predominantly Black Deaverview apartments is inside the city limits but not the school district. The same goes for Spruce Hill Apartments in East Asheville.

Census records clearly show that the Black population decreased by nearly a quarter within the census tracts lying inside of the city schools district from 2010 to 2020. In the areas of Buncombe County surrounding the district’s tracts, it increased by around 20 percent.

There’s more. When the former Lee Walker Heights apartments were demolished residents were promised the opportunity to return once Maple Crest apartments were constructed in its place. Because of the corrupt and eviction-happy Asheville Housing Authority (where Sandford works and Freeman sits on the board) and continued gentrification during covid, many did not return. If those residents’ children attended Asheville City Schools their families were suddenly faced with a difficult and costly decision.

If an in-district white student requested the same spot at APS as a Black out of district student, the district was legally required to place the white student at APS first.

Other elementary schools accept new students of any grade K through 5. But because the Montessori program was in the process of growing its classrooms, APS could not accept new 3rd graders, let alone 4th or 5th graders. Though the program finally expanded to 4th grade, it was prohibited from opening enrollment for all but two weeks in June and was made to refuse new students with the exception of siblings of current students, preschoolers, and kindergartners in its final year.

This made Asheville Primary School yet another canary in the coal mine of both West Asheville and the city at large. It’s honestly miraculous that 13 percent of Asheville Primary School’s student population was still Black given an entire system seemingly hellbent on driving Black students out. This fact is also a testament to the quality of the program.

So Asheville Primary School was hardly the root of city schools’ budget problems. The real issue lies with the fact that the district has been hemorrhaging students since the central office shot itself in the foot by tightening its enrollment policies.

Not shockingly, due to these policies furthering gentrification, the district’s percentage of white students went up, enrollment went down and its budget went down. But Asheville Primary School got the blame, because “equity.”

But dozens of locals would reject this, show up, and speak out for Asheville Primary School, creating a seismic shift that nearly saved one of West Asheville’s dearest communities.

To save a school

“If the board and district leadership are confident in their convictions against supporting Asheville Primary, you should have the courage to hold a discussion under an elected school board. I have many more thoughts that cannot possibly be shared in just a few minutes. So I will say in closing that I am just relieved to no longer be an employee of the district, so that I am able to speak freely.”

– Liza English-Kelly, during the Dec. 7 meeting. She’s since been elected to the school board

“What backs APS for me is something called peer reviewed research and data driven decision-making. Most of the top blue ribbon schools in this country right now are public montessori schools. South Carolina is closing an opportunity and achievement gap that you can drive a truck through. Sounds familiar.”

— former school board member Jackie McHargue at the Dec. 13 school board meeting.

After wrecking their own budget while pushing Black students out of the district, the central office and school board attempted to cast themselves as saviors of Black students in the December meetings that would decide Asheville’s primary’s fate. Only a day’s notice was given for the first public hearing despite state law requiring at least 48 hours notice. Still, locals spoke out and stood by their convictions to save their school.

For a moment it seemed like they would have only one hearing, before the school lawyer — wary of how blatantly they had already broken open meetings law — advised otherwise and they scheduled another a week later. Speakers at these hearings included Black parents, parents of disabled children, and the kids themselves.

“I would prefer that you would keep this school open,” Kiera Mormon said during the Dec. 7 public hearing. “They learn like things that’s not only book knowledge, but like real social things, things that are really gonna matter in the life of a person, things that are important.”

“My daughter loves this school, and I love it,” she continued, tearing up after her child hugged her. “And I prefer you find a way and find the money. However you want to do it. Hey, I’ll donate, but please keep this school open. That’s all we’ve got to say.”

“You guys talk about funds. There are plenty of funds. You can draw that from just about anywhere. I know that, why? Because I’m in business law,” Taysia Elliott, mother of an Asheville Primary student, said on Dec. 7, “If you close this school, think about how many children will lose the one place where they can come together and learn, and grow as a community.”

Sybriea Lundy, a parent of a biracial kindergartener with down syndrome, said her daughter “has made leaps and bounds in the three months she has been there.”

“The fact that she can say her ABCs and count is phenomenal. We never thought our daughter would make this much progress. Every day, I see her blooming. I am here before you today a formerly incarcerated mother of a biracial special needs child to ask you to please, take a chance on my kid.”

Beth Mayberry, a teacher at Asheville Primary, discussed a biracial family that counted on the school remaining open. “They lived in Pisgah View for 10 years.” The father, who was Black, had been fighting to find section 8 housing, rejecting “five or six houses” that weren’t within the school district limits. Finally, settling on a house within walking distance of the school, the family signed a lease.

“This week, the family just moved into a house in the Burton Street neighborhood that’s a seven minute walk to Asheville Primary School. He asked me to ask you to please keep the Asheville Primary School building open so that his children can continue to go there through fifth grade.”

“I have a low-vision learner who is legally blind. I also have an autistic kid. And their ability to be in the classroom is different, but because of the model, they are the same,” Lindsey Brathen said. “When there’s areas where they have hardships, their peers are allowed to come beside them and show them, and then in the areas where they are the best at, they are allowed to shine.”

“He’s struggled with sensory issues, generalized hesitancy, and social skills for much of the last few years,” said Erin Dunn of her kindergarten child at Asheville Primary. “His progress in just the last three and a half months has been remarkable.”

“Don’t close our school. Our special teachers are good. You don’t have to do the same thing as everybody else,” said Hollis, a Asheville Primary student reading a comment by Otis, a classmate.

“Schools are a community where children feel safe, and when children feel safe, they’re able to learn. During the current pandemic and resulting mental health crisis in so many children, this is more important now than ever,” Ann Lanzey, a school psychologist said, fighting tears. “If the children from Asheville Primary are dispersed out to other schools then all school communities are significantly disrupted.”

The well-researched and heartfelt entreaties by this large multiracial and multigenerational group would be met by none other than people in privileged central office and non profit positions claiming that keeping Asheville Primary School open was the real racism. Here’s how they went about constructing this web of lies that the school board used as cover to close a school.

The equity wash

“Closing this school won’t solve your problems. You have been too reactive and short term in your thinking and your actions. School closings and consolidation should be an inclusive open process that involves all communities affected and it needs to be part of a long [claps] term [claps] strategic [claps] plan [claps] with benefits for all children. [Members of the crowd cheer]. Build a long-term vision with families. You promised we’d stay open. You promised we’d keep our school number. You promised we’d expand to fifth grade and become a full elementary school like others in ACS, but you had no plan.”

—Lara Lustig during the Dec. 7 school board meeting.

“What I witnessed last week as community leaders and stakeholders literally stomped their feet and clapped their hands as they spoke to you.”

— School of Inquiry and Life Sciences principal Nicole Kush in the Dec. 13 school board meeting criticizing a ‘lack of civility’ in the Dec. 7 meeting.

But despite using the common trick of invoking “equity” to prop up the same old status quo, few beyond central office cronies came out to support the closure at the Dec. 13 meeting. Parents of kids in other schools and even teachers more often than not expressed solidarity with Asheville Primary. It went both ways: those fighting to save Asheville Primary often expressed solidarity with the needs of those at other schools.

At the end of the day, it was high-paid members of the bloated central office that pushed hardest for closure. The attack was also led by current and former board members and staff of the Asheville City Schools Foundation. Astoundingly they claimed the school was a white, racist institution, ignoring the Black parents and children fighting to save Asheville primary.

“It’s not our job to question you publicly,” Asheville High School principal Derek Edwards said at the Dec. 13 meeting, while chiding people trying to save their school. Edwards is on the board of the City Schools Foundation.

Student Services Coordinator Tanya Presha falsely said that the school system was broke while claiming that a state takeover of the school system was imminent, “We’re going to lose admin and we’re going to lose our jobs.”

She then defended the superintendent, “Dr. Gene has suffered for that, and now he is trying to make it right,” and with a broad stroke, claimed that parents attempting to save APS were racist. “Last week was very hurtful for me as a Black native and a professional,” she said, claiming she had been disrespected without mentioning how.

Copeland Rudolph, executive director of Asheville City Schools Foundation, quoted anti-racist journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones out of context: “‘We cannot say we want equal educational opportunities for all children and then fight to advantage our own.’”

Schools Foundation board member Kate Shem also pushed for the closure of Asheville Primary by invoking Hannah-Jones. By this point a listener who didn’t know better might wrongly assume that Hannah-Jones tours the country leaving school closures in her wake.

Marta Alcala-Williams, executive director of equity at Asheville City Schools and a former board member at the city schools foundation, advocated for closure while asking those fighting to save the school to “check your privilege and check where this is really coming from.”

Remember this was at the same time that teachers and city schools employees against closing Asheville Primary were facing retaliation for their views.

If there’s more to this coordination on messaging between high level district staff and current and former members of the school foundation, the district ain’t sharing. Records requests for communications about the issue from the central office to Asheville city hall and the City Schools Foundation — which are clearly public record under state law — were denied after district staff simply refused to comply with them. This is a blatant violation of open records law, but the school district didn’t stop there.

Acebo claims that the central office and school board rigged public comment at the Dec. 13 meeting by snatching away the sign-up sheets before the meeting “with people standing in the line to sign up. They took them away so that privileged people could sign up or make people sign up, so they had central office staff sign up and they had Asheville City Schools Foundation.”

If that’s the case it also broke open meetings law, which requires that speakers of all views on a matter before such a board be treated the same.

Clearly this rigging had the intended effect, ending the fight to save Asheville Primary School in the same underhanded fashion in which it was started. The board moved forward with its preconceived plans. By a 3-2 vote — with members Sandford, Sieburg, and Martha Gietner voting for and Chair James Carter and member Peyton O’Connor voting against — the closure passed, leaving a community devastated.

This will happen again

“We’re not making adequate investments in housing that would allow the demographics that support the [desegregation] order to continue. At what point does that stop being our problem and start becoming another governing body’s problem for enabling larger urban planning forces to perpetuate segregation?”

— School board member Peyton O’Connor during the Jan. 28, 2022 meeting

“Governments have ever been known to hold a high hand over the education of the people. They know, better than anyone else, that their power is based almost entirely on the school. Hence, they monopolize it more and more.”

— Francisco Ferrer, anarchist educator, killed by firing squad for his work

Unfortunately, the district’s damage has continued beyond the closure of Asheville Primary to a refusal to pay staff their due. Around the same time they moved to close the school central office refused ACAE’s demands for pay that would keep up with inflation. Carter would even claim that a few low-paid employees logging a few hours they did not work was the real “equity issue,” rather than the district’s insistence upon paying poverty wages.

After yet another fumbled application for the Early Childhood Education grant, where it applied for funds to pad its self-inflicted budget deficit instead of finding other locations for its preschool classrooms, Asheville City Schools would unceremoniously eliminate all four of the preschool classrooms dislocated by the closure at APS. This was a major blow amidst an assault that has reduced preschool enrollment by over 40 percent in three years, and Buncombe County officials even blasted the central office for it in an open letter.

In a January meeting central office staff openly discussed surveilling teachers and students, even to the point of installing microphones around every teacher’s neck. And at the same time, school bus ridership and students needing free and reduced lunch are exploding as Asheville continues to be the worst place to live in the country due to a skyrocketing cost of living.

When asked in an interview with the Blade what could be learned from the long, exhausting fight, Lara Lustig replied, “I don’t trust these people anymore. I have no reason to.”

But those fighting to save Asheville Primary did deter the system from shutting down any more schools — for now. Finance director Georgia Harvey, addressing the board in April, declared that school closures held no place in the upcoming budget, noting “at your request, we could not do that next year.”

In the wake of public backlash Freeman announced his retirement. Communications director Ashley Michelle Thubin, who illegally refused to fulfill public records request for more than a year, announced her resignation in May.

But still, the district refuses to budge on its enrollment policies, and the number of students in the system keeps plummeting.

In November four new school board members were finally elected after state law changed Asheville’s archaic system, a shift in a board that’s been relatively untouchable. But again, the school district contains less than half of the city’s population, and that part of the city is enduring the absolute worst of gentrification. Countless residents were removed from the city school district before they could ever cast a ballot for candidates advocating to save Asheville Primary and pay teachers and staff fair wages, a necessary ingredient should enrollment ever sustainably expand.

Liza English-Kelly joins the school board as the only one of the newly elected members to show up when Asheville Primary faced the chopping block.

Rebecca Strimer was a former board member at the Asheville City Schools Foundation and supported Asheville Primary’s closure.

Sarah Thornburg is an estate planning attorney with the conservative real estate law firm McGuire, Wood, and Bissette.

The top vote-getter was Amy Ray, who works for the federal prosecutors office, has city schools foundation affiliations, and also sits on the housing authority board. That isn’t a joke. Ray has somehow managed to spend her life becoming the walking embodiment of every part of the prison industrial complex.

Even an elected school board will just as surely betray our community. Real change, as always, isn’t on the ballot, especially not in a city where racial and economic disparities are this extreme.

But just as the march to school closures will happen again, powerful resistance like that shown by the community that fought hard for Asheville Primary is the only thing that can stop it. Whether at school board meetings, at city council, in the halls of county commissioners, or in the streets, more is needed, not less.

Despite cuts to some of its positions the central office remains incredibly bloated. With determination to continue a racist status quo it will continue tripping over its own ego and endless incompetence until its either stopped or there is nothing left to destroy. Those determined to fight for schools like APS should keep making their lives hell.

We still don’t know every detail about why officials were so hellbent on closing the school. Perhaps, in the years to come, more of the true reasons why Asheville Primary was so viciously attacked will emerge. Perhaps as many have stated, with the ruinous expansion of I-26 will come the rise of a hotel at 441 Haywood Road. It’s certainly easier to eventually sell a building used for storage than it is a building full of children. The fight for schools would have to once again become a fight for Asheville.

For those new to these drawn out battles with bureaucracies, it can be difficult to imagine that school officials so ostensibly devoted to the childrens’ lives would intentionally wreck them and inflict such a cost on parents and communities. But unfortunately the lies and attacks by directors like Freeman and his allies on the board are more the rule than the exception.

Playing nice with the school board, whoever sits its dais, isn’t the support children need as they forge their identities and the skills to tackle the many issues they face. It’s not the setting teachers and staff need in order to support these children. Many work in environments already cut to the bone, fear reprisal from the central office, and struggle to find housing in the district, let alone feed their families.

Moves to close beloved schools like Asheville Primary will happen again (and soon). The task of fighting them can’t just be left to parents, teachers and neighborhoods under the gun; we all have to back them up. Otherwise local education will end up just one more thing that the gentry sell for parts.

—

Matilda Bliss is a local writer, Blade reporter and activist. When she isn’t petsitting or making schedules of events, she strives to live an off-the-grid lifestyle and creates jewelry from local stones

The Asheville Blade is entirely funded by our readers. If you like what we do, donate directly to us on Patreon or make a one-time gift to support our work. Questions? Comments? Email us.